Evidence from a remote site on Sulawesi reveals that ancient human relatives crossed a deep ocean barrier more than a million years ago. The discovery extends the earliest known human movements in Southeast Asia.

New research shows an early hominin sea crossing to Sulawesi at least around 1.04 million years ago and possibly as early as 1.48 million years ago.

Hominins are the group of primates that includes modern humans (Homo sapiens) and all our extinct ancestors and close relatives (e.g., Australopithecus, Homo erectus, Neanderthals) after the lineage split from the chimpanzee line around 7 million years ago.

However, it’s important to distinguish that not all hominins were the same species as modern humans. Modern humans (Homo sapiens) are the only surviving hominin species today. There have been numerous hominin species over time, each with distinct characteristics and adaptations.

Key characteristics that distinguish hominins from other primates and link them to the “human” branch include:

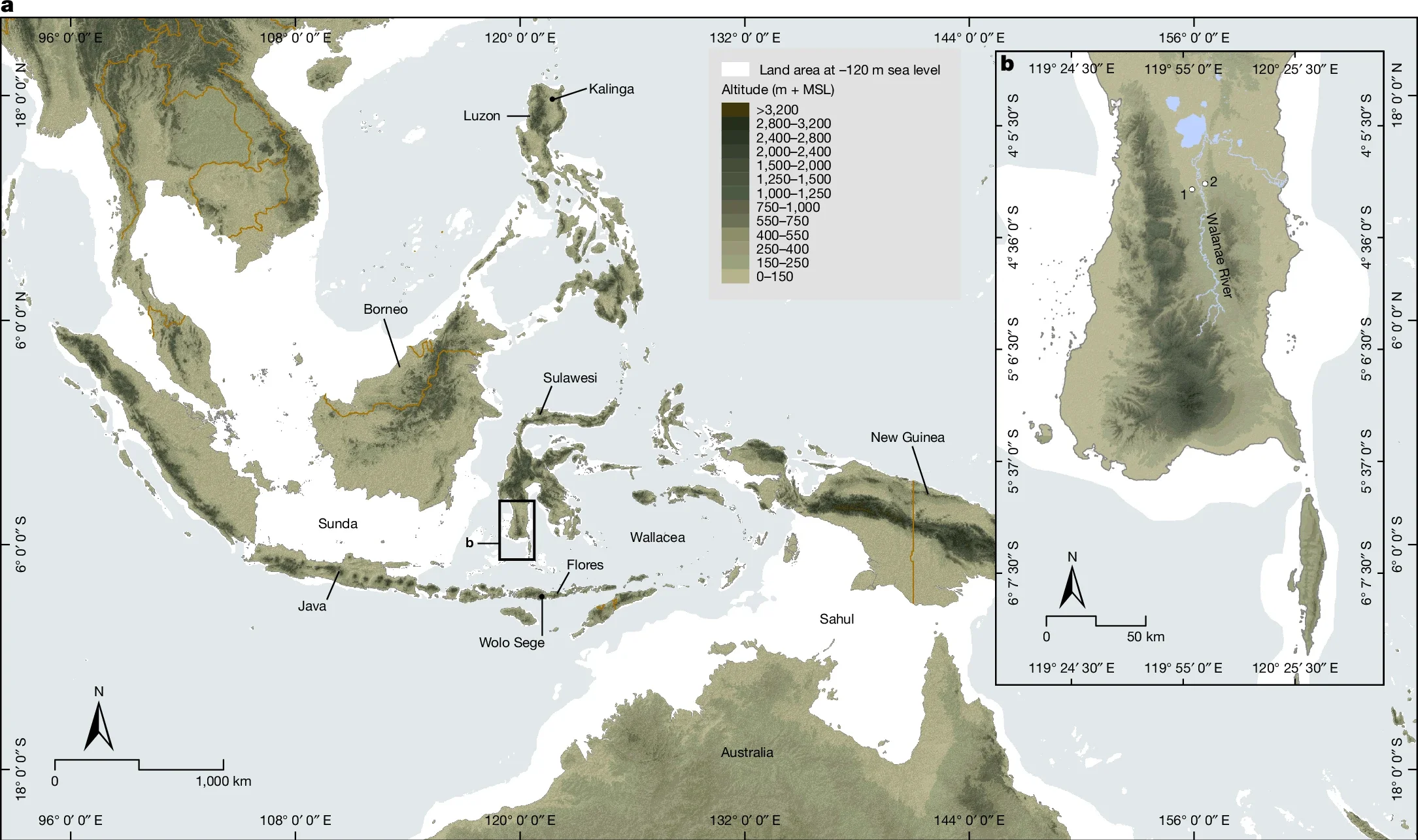

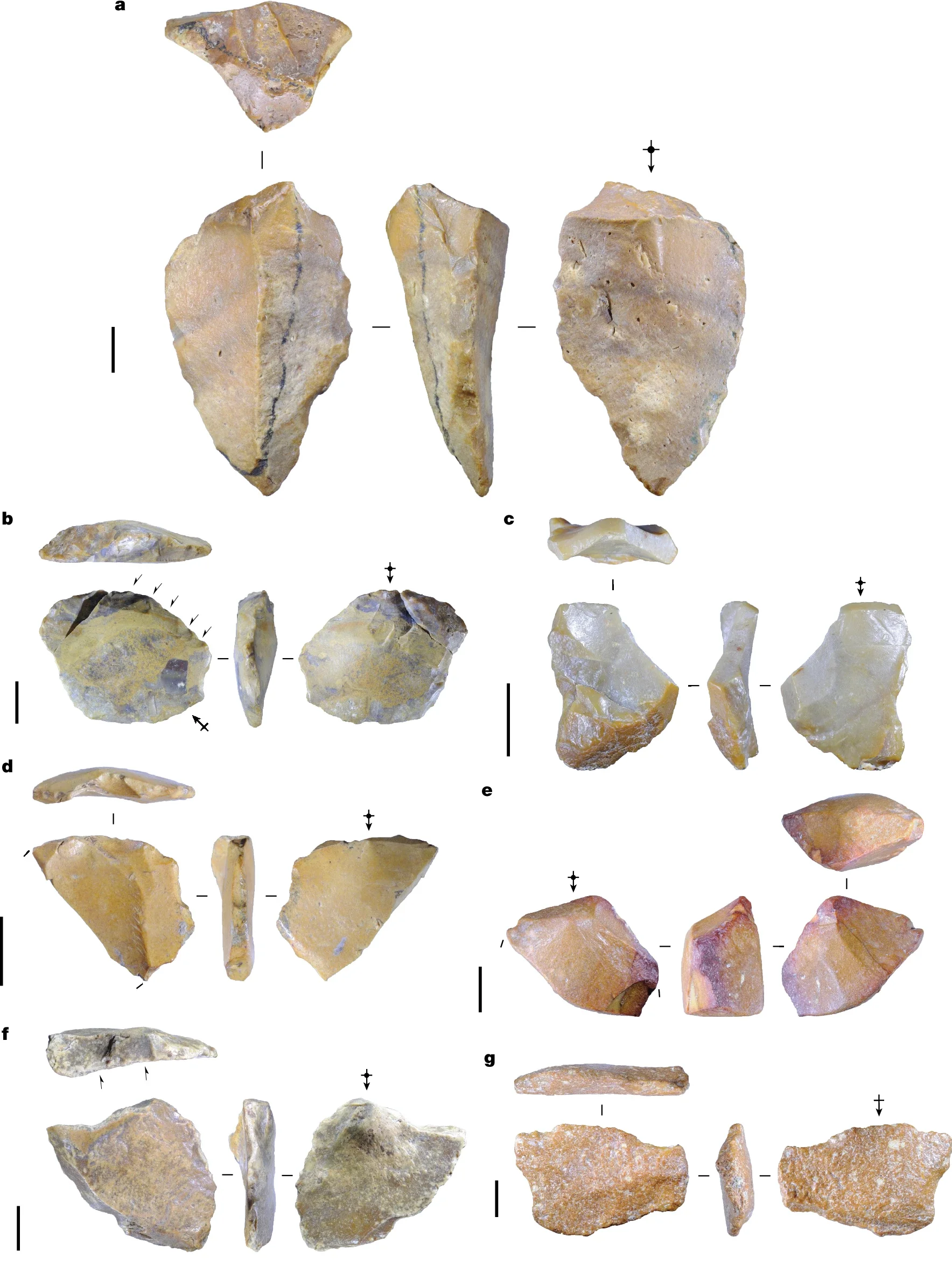

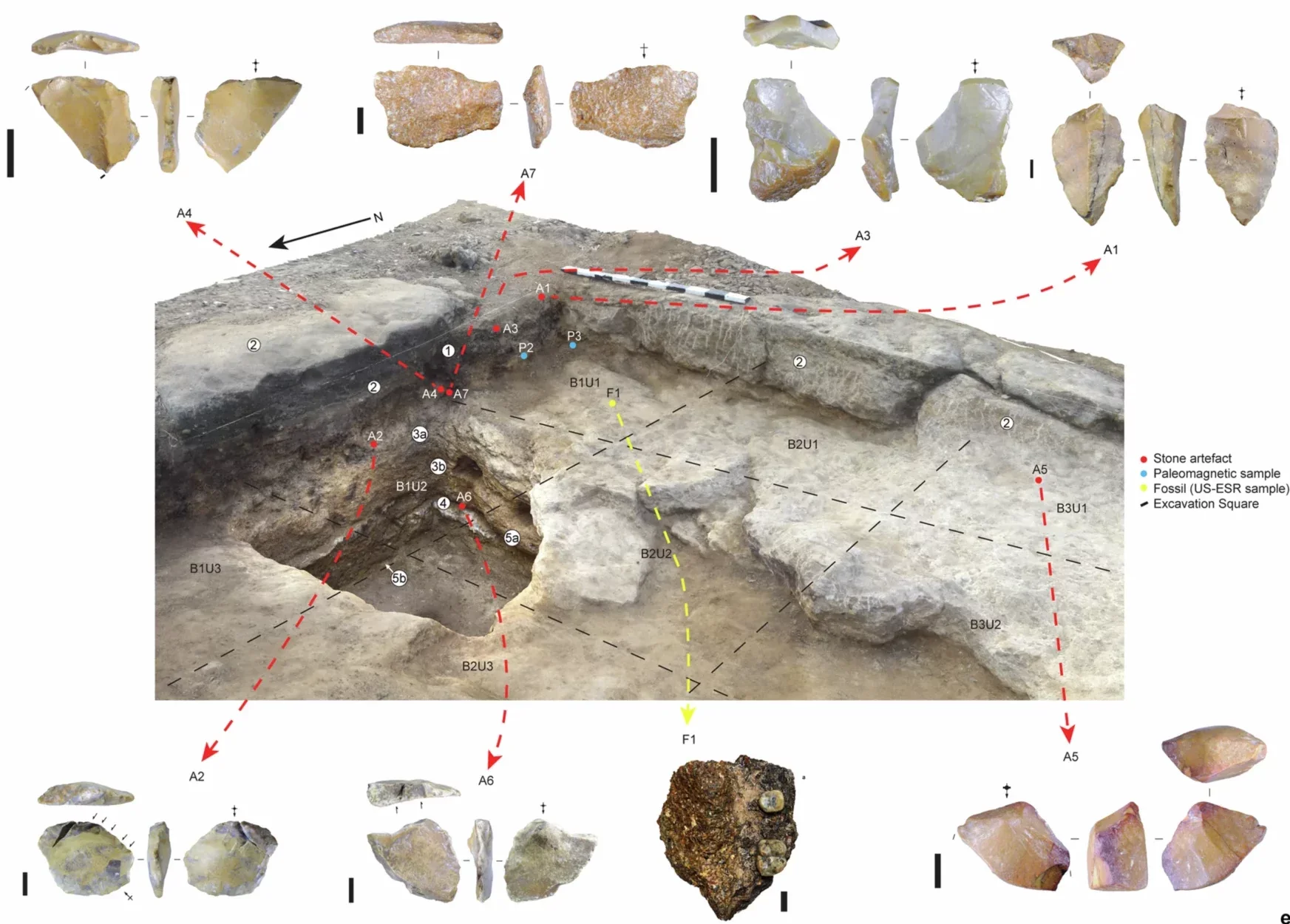

Archaeologists led by Budianto Hakim from Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency and Professor Adam Brumm at Griffith University uncovered seven stone flakes. These artifacts came from the Calio site in southern Sulawesi, embedded in sandstone layers within a cornfield that once was an ancient river terrace.

Using palaeomagnetic dating of the sandstone and direct Uranium‑series and electron spin resonance dating of a pig jaw fossil gave a firm age of at least 1.04 million years. Some estimates extend that up to 1.48 million years. The team published these results in Nature.

These flakes show sharp-edged craftsmanship. They likely served as cutting or scraping tools. The early tool‑makers probably struck larger pebbles from nearby riverbeds. One flake even appeared retouched, showing advanced flaking technique.

This find significantly predates the earlier known Sulawesi site at Talepu, which dated to about 194,000 years ago. It also aligns with stone tool evidence on Flores at Wolo Sege dated to at least 1.02 million years.

The island of Sulawesi lies well east of the Sunda continental landmass. Deep sea channels separate Wallacea from mainland Asia. Modern Homo sapiens only crossed these waters in the last 100,000 years.

The new site suggests these ancient tool‑makers made an early hominin sea crossing across deep water far earlier. The method remains unknown. Brumm suspects accidental rafting on vegetation mats during storms or tsunamis. He notes advanced planning for boat use likely lay beyond these early groups.

The identity of these tool‑makers remains a mystery. No hominin bones have been uncovered. Scientists consider possible makers include Homo erectus, known in Java about 1.6 million years ago. Relatives of Homo floresiensis or Homo luzonensis are also candidates.

Brumm wonders: if tool‑makers came from Sulawesi, could they have evolved differently from the small‑bodied florensiensis on Flores? Sulawesi’s area is over 12 times that of Flores. Isolation in such a large, ecologically diverse island might lead to unique adaptations.

Across Wallacea, other islands hold earlier or later evidence of ancient human relatives. On Flores, Wolo Sege tools date to at least 1.02 million years. Luzon in the Philippines yielded artifacts and faunal marks dated between 631,000 and 777,000 years ago. Flores later hosted Homo floresiensis and Luzon held Homo luzonensis remains. These findings suggest island Southeast Asia hosted multiple dispersal events over the Pleistocene. The Calio discovery now stands among the oldest in Wallacea.

Experts call the Wallace Line a key transitional zone. East of it, life evolved in isolation. The presence of hominins here over a million years ago challenges assumptions about where early humans could survive. It also adds complexity to migration models that emphasize land routes alone.

Hakim and Brumm propose more systematic surveys on Sulawesi. Its rugged interiors and caves may hold undetected artifacts or even hominin fossils. Brumm predicts exciting discoveries await researchers prepared to explore persistently and patiently.

Past studies and findings have laid important groundwork leading to this discovery. On Luzon in the Philippines, evidence of early hominin activity, including stone tools and bones marked by cutting, dates between 631,000 and 777,000 years ago. Another Sulawesi site, Talepu, previously revealed stone artifacts about 194,000 years old.

Further anatomical studies, such as recent research by Pietrobelli et al. (2025), analyzed the ankle bones of Homo floresiensis, concluding that these early humans had joints adapted for both walking upright and climbing. These combined findings indicate multiple episodes of early hominin dispersal throughout island Southeast Asia, significantly revising our understanding of ancient human migration and adaptability.

These findings reshape views about early human voyages across oceans. They show ancient hominins crossed deep water before modern humans. With new evidence, researchers can test migration models across Wallacea. Discovering fossils on Sulawesi could identify novel human relatives.

Understanding adaptations in such isolation may offer broader insights into human flexibility. It may spark interest in refining sea‑crossing mechanisms in early evolution. The research also raises awareness of island archaeology in understudied regions, driving future fieldwork.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Million‑year‑old tools reveal early human sea crossing near ‘Hobbit’s’ island appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.