A tight clump of four star clusters sits in the Perseus galaxy cluster, and at first glance it looks like nothing special. No bright spiral arms. No obvious central bulge. Not even the soft smudge you would expect from a faint dwarf galaxy.

That emptiness is the point.

Astronomers say those four globular clusters, plus an almost ghostly halo of starlight around them, mark the location of an “almost dark” galaxy, one that carries a huge load of dark matter while forming very few stars. The object is called Candidate Dark Galaxy-2, or CDG-2, and it may be among the most extreme examples yet of a galaxy where the usual luminous stuff barely registers.

The work is reported in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

CDG-2 did not announce itself through a patch of diffuse light, the way many ultradiffuse galaxies were first found in the last decade. Instead, it appeared as a statistical signal, a suspiciously tight overdensity of globular clusters that did not seem attached to any normal, bright galaxy.

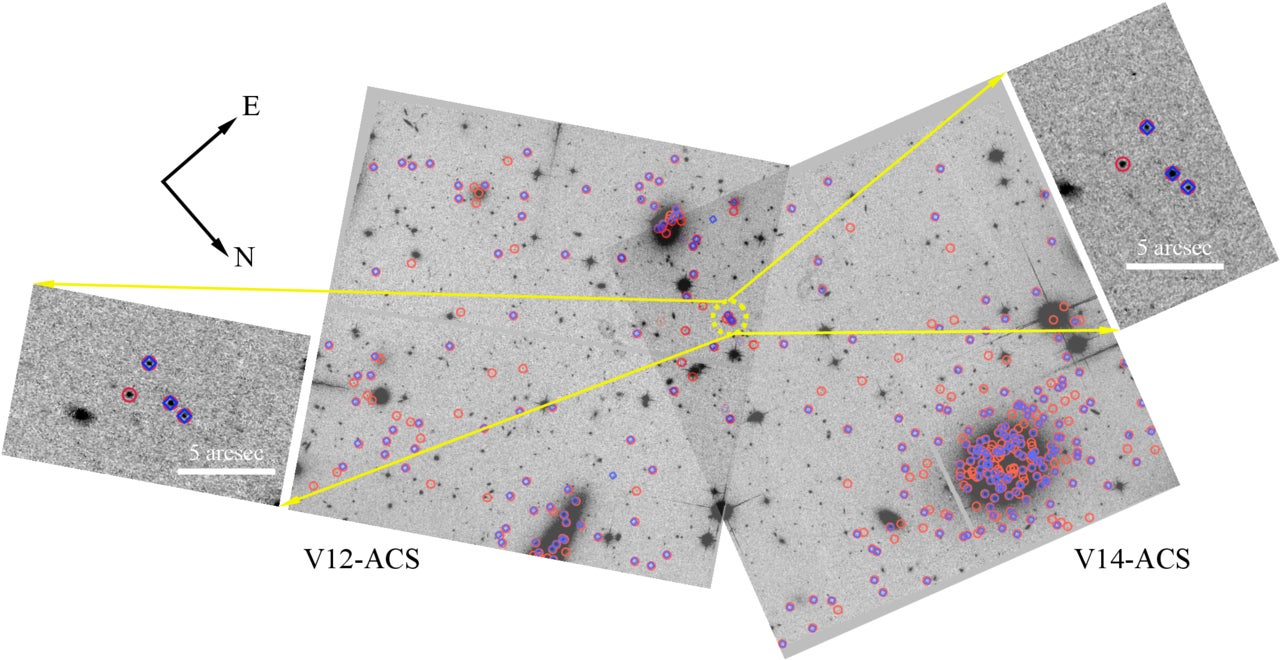

David Li of the University of Toronto and colleagues built on earlier efforts to search the Perseus cluster using globular clusters as signposts. The data come from the Program for Imaging of the PERseus cluster (PIPER), a Hubble Space Telescope imaging survey of Perseus conducted with the Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Camera 3. The team used globular cluster catalogs derived from those images and ran an updated statistical model designed to flag unusual cluster groupings.

In plain terms, their method treats the points of light in an image as coming from three overlapping populations: clusters drifting in the intracluster environment, clusters tied to normal luminous galaxies, and clusters that might belong to ultradiffuse or nearly dark galaxies. The model then searches for likely centers of hidden galaxies. It does that through a transdimensional Markov Chain Monte Carlo approach, producing a probability map for where an unseen galaxy could sit.

In two separate Hubble imaging visits, the same compact cluster grouping kept turning up.

The updated analysis used a newer globular cluster catalog built with DOLPHOT, a photometry package suited for point sources. That catalog went slightly deeper than an older one built with DAOPHOT. With the less stringent selection, the researchers picked up an extra globular cluster candidate near the original three, bringing the CDG-2 count to four.

That one addition changed the math.

Using the updated catalog, the study reports that the probability of a hidden ultradiffuse or dark galaxy at the CDG-2 location is roughly 2,000 times higher than the prior expectation used in the model. In the earlier DAOPHOT-based work, the same location had stood out at about 200 times the prior, so the new signal is about ten times stronger.

The four clusters span about 32 arcseconds on the sky. At the assumed Perseus distance of 75 megaparsecs, that corresponds to roughly 1.2 kiloparsecs across. The authors estimate the chance of seeing four such globular cluster candidates packed that tightly, purely by random background clustering, is about 1.5 × 10⁻⁵. Put another way, you would expect a configuration like that only once in roughly 67,000 Hubble images of similar size and noise properties.

The model also assigns a high probability that those four clusters belong to the same object. The maximum a posteriori estimate gives a 94% ± 0.5% probability that all four are members of the detected system, while other cluster candidates in the same images each have at most about a 0.5% chance of belonging to CDG-2.

Statistics alone do not make a galaxy. The team then tried to see whether any diffuse starlight actually surrounds the clusters.

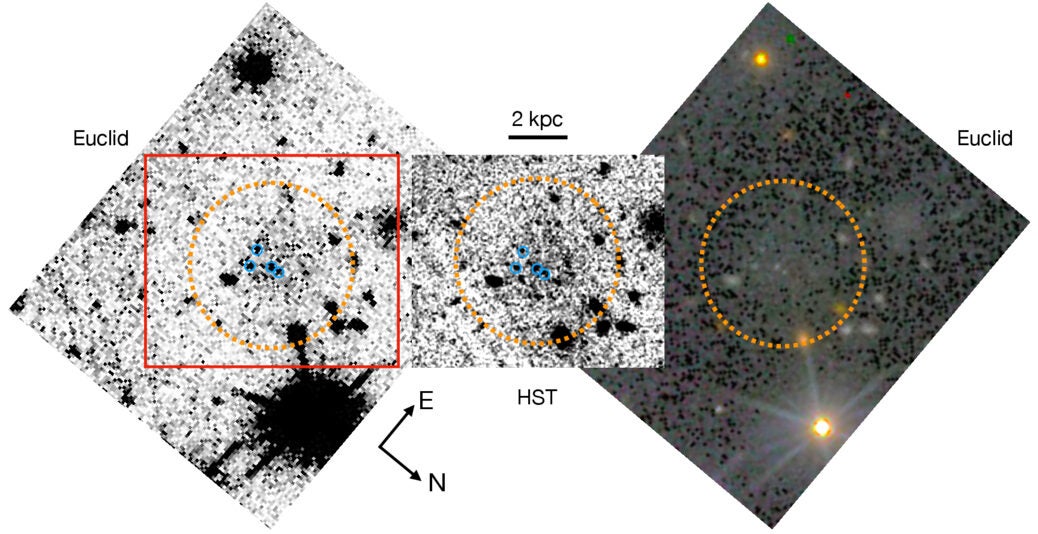

They stacked two Hubble images that both include CDG-2, and a weak but significant diffuse component emerged around the globular clusters. To check that this glow was not an artifact, the researchers turned to a completely different dataset: Euclid Early Release Observations of the Perseus cluster.

Euclid’s imaging, optimized for detecting diffuse structure, showed extremely faint emission with nearly the same morphology seen in the stacked Hubble data. With two independent observatories showing matching features at the same spot, the authors argue that CDG-2 is “almost definitively” a real galaxy. They note that spectroscopy, potentially from a powerful facility such as the James Webb Space Telescope, would provide a more direct confirmation and help lock down the distance.

Using Euclid’s VIS imager, the researchers performed a preliminary measurement of how much of the galaxy’s light comes from the globular clusters themselves. They modeled the clusters with point-spread-function photometry and the diffuse glow with elliptical isophote fitting, iterating the process to reduce interference between the two components.

Because the galaxy is so faint, the authors emphasize uncertainties. The center of the diffuse emission is not sharply defined, and it appears offset from the cluster grouping. They also ran a mock-galaxy injection test to estimate how much light might sit outside the fitted isophotes, finding that about 86% of the diffuse light falls within their fitted range and applying a correction.

Their final estimate puts CDG-2’s total V-band luminosity at roughly 6.2 ± 3.0 million times the Sun’s luminosity. In their measurement, the mean fraction of light coming from the globular clusters is 16.6% ± 2.0%.

Independent checks with Subaru Hyper Suprime-Cam g-band data produced a globular cluster light fraction of about 18%, while noisier CFHT MegaCam data gave about 22%, supporting the idea that the basic result is not driven by one instrument.

The study does not claim a single definitive value for CDG-2’s true globular cluster fraction, because correcting for undetected faint clusters depends on assumptions about the globular cluster luminosity function. Still, the authors explore what happens under a canonical luminosity function. If the four detected clusters represent roughly half the total cluster light, then the globular cluster light fraction could be closer to 33%, with a globular cluster stellar mass fraction around 28% under mass-to-light assumptions drawn from earlier work.

Even the conservative lower bounds are striking. The paper argues that CDG-2 may be the galaxy with the most extreme globular cluster light and mass ratios found so far.

Then there is the dark matter angle.

The authors discuss empirical relations that link globular cluster systems to a galaxy’s dark matter halo mass. If those relations apply to CDG-2, the implied halo mass could be on the order of 10¹⁰ to 10¹¹ solar masses, while the stellar mass estimate is about 1.2 × 10⁷ solar masses. That mismatch points to an object dominated by dark matter, potentially at the 99.9% level or higher, though the study stresses these numbers rely on extrapolations and need kinematic data for confirmation.

CDG-2 also reshapes the conversation around another candidate, CDG-1, which still lacks a detected diffuse component despite targeted follow-up. If CDG-2 is real, CDG-1 might be even more extreme, or it might sit at a different evolutionary stage.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The original story “Nearly invisible galaxy may be built mostly of dark matter, Hubble finds” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Nearly invisible galaxy may be built mostly of dark matter, Hubble finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.