A team of researchers has identified a previously unrecognized hub for waste clearance in the human brain, located along a major artery supplying the brain’s protective outer layer. This discovery, published in iScience, provides an updated map of the brain’s lymphatic drainage system and offers a new framework for understanding how the brain maintains its health.

The brain is encased in a set of protective membranes called the meninges. For a long time, these membranes were thought to isolate the brain from the rest of the body’s immune system. More recent research has overturned this idea by identifying a network of lymphatic vessels within the meninges that drain waste-filled fluid away from the brain. Understanding this drainage system is essential for developing new approaches to neurological and psychiatric conditions.

A research team led by Onder Albayram, an associate professor at the Medical University of South Carolina, has been working to map this intricate network in living humans. Their work aims to establish a clear picture of how these structures function in a healthy state. This knowledge can serve as a baseline to identify changes that occur in conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, brain injury, or as a consequence of aging.

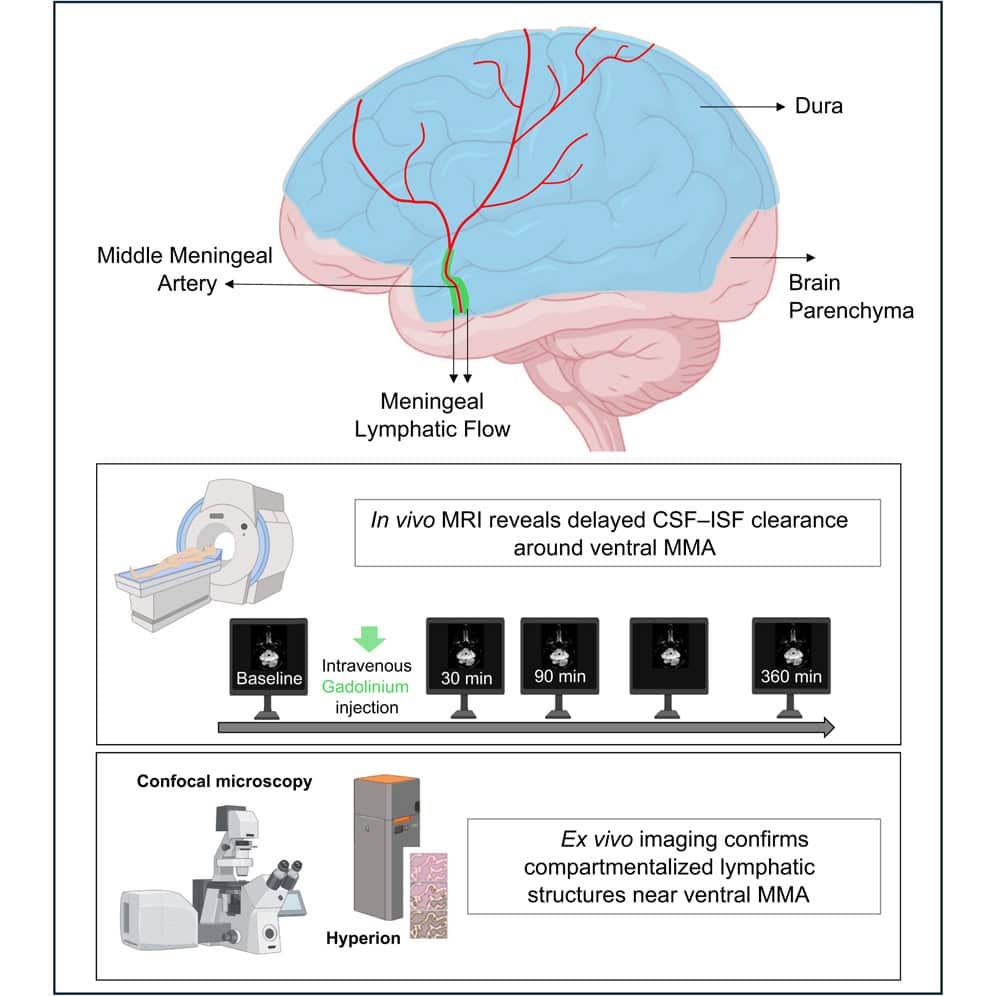

To investigate these drainage pathways, the researchers conducted a study on five healthy participants. The team used a dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique, originally developed through a partnership with NASA to study fluid shifts in astronauts. Each participant received an injection of a contrast agent, and their brains were scanned at several intervals over a six-hour period, allowing the scientists to track the movement of fluid.

The researchers focused on the middle meningeal artery, a significant vessel in the dura mater, which is the outermost layer of the meninges. They measured the signal intensity of the contrast agent both inside the artery and in the tissue immediately surrounding it. The signal inside the artery peaked quickly and then faded, which is the expected pattern for blood flow as the agent is cleared from circulation.

In the tissue surrounding the artery, however, a different pattern emerged. The signal from the contrast agent increased slowly, reaching its peak 90 minutes after injection before gradually declining. This delayed clearance suggests a much slower fluid movement, inconsistent with the rapid dynamics of blood circulation. Albayram explained the observation, stating, “We saw a flow pattern that didn’t behave like blood moving through an artery; it was slower, more like drainage, showing that this vessel is part of the brain’s cleanup system.”

To verify that this slow-moving fluid was flowing through genuine lymphatic vessels, the team needed to examine the anatomy of the region at a microscopic level. They obtained postmortem human dural tissue and used two different advanced imaging techniques to map its cellular architecture. One method, immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, uses fluorescent tags to light up specific proteins. The other, Hyperion Imaging Mass Cytometry, uses metal tags to achieve highly detailed, multi-layered images of different cell types simultaneously.

These high-resolution analyses confirmed the presence of a dense and organized network of lymphatic vessels in the dura surrounding the middle meningeal artery. The vessels were identified by the presence of key proteins that act as markers for lymphatic cells. This anatomical evidence provided a physical basis for the slow drainage patterns observed in the MRI scans, linking the functional imaging data directly to cellular structures.

The researchers also noted that the structure and organization of these lymphatic vessels varied across different layers of the dura. This complexity suggests a sophisticated and compartmentalized system for fluid management. The findings expand the known map of the brain’s lymphatic drainage system, adding a key ventral, or bottom-facing, pathway to the previously documented dorsal pathways along the top of the brain.

It is important to note certain limitations of the research. The MRI portion of the study involved a small group of five individuals, and the histological analysis was conducted on tissue from a single donor. The imaging data provide indirect evidence of fluid movement based on the behavior of a contrast agent, rather than a direct measurement of flow. Future studies with larger and more diverse groups of participants will be needed to confirm and expand upon these findings.

The work establishes a new reference point for understanding the brain’s normal function. By charting how the healthy brain clears waste, researchers can better identify when and how this process becomes impaired. Albayram’s team is already applying these insights to study patients with neurodegenerative diseases, hoping to find new ways to diagnose and treat these conditions.

“A major challenge in brain research is that we still don’t fully understand how a healthy brain functions and ages,” said Albayram. “Once we understand what ‘normal’ looks like, we can recognize early signs of disease and design better treatments.”

The study, “Meningeal lymphatic architecture and drainage dynamics surrounding the human middle meningeal artery,” was authored by Mehmet Albayram, Sutton B. Richmond, Kaan Yagmurlu, Ibrahim S. Tuna, Eda Karakaya, Hiranmayi Ravichandran, Fatih Tufan, Emal Lesha, Melike Mut, Filiz Bunyak, Yashar S. Kalani, Adviye Ergul, Rachael D. Seidler, and Onder Albayram.