Catching pancreatic cancer early is among the most difficult challenges faced by medical providers, and that delay often ends in death. The NIH-supported researchers’ discovery of a new blood test, however, may be able to locate and diagnose people with pancreatic cancer sooner rather than later. This would allow for an increased opportunity for successful therapeutic intervention.

Researchers reporting in Clinical Cancer Research from the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and the Mayo Clinic state that they found a blood test measuring four proteins may accurately identify patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Early-stage cancer is often the most amenable to treatment.

PDAC is the most prevalent form of pancreatic cancer and one of the most lethal. Although one out of ten patients diagnosed with PDAC will live for five years or longer after a diagnosis, the overall percentage remains very low.

That low survival rate is primarily due to the fact that most symptoms present late in the course of illness. By that point, the disease is generally already disseminated, and there is no current standard screening test available for asymptomatic individuals.

“The primary barrier to early detection of PDAC is that current blood markers are unable to differentiate between benign and malignant disease,” Kenneth S. Zaret, PhD, the principal investigator of this project at the University of Pennsylvania, said. “When PDAC is detected earlier in the disease continuum, it provides a much greater opportunity for intervening effectively.”

Why has it been so difficult to detect PDAC earlier in the disease continuum than is currently typical?

Currently, the CA19-9 marker is used to monitor how patients respond to therapy, but it does not provide adequate screening capability. The CA19-9 marker can become elevated in nonmalignant disease processes such as pancreatitis or obstructive bile duct disease.

Additionally, not all individuals will generate the CA19-9 marker as a result of genetic predisposition.

Additional blood markers currently under investigation include thrombospondin 2 (THBS2). While its effectiveness for screening healthy individuals is limited, it has demonstrated some degree of success in identifying people who have pancreatic cancer or precursors for developing pancreatic cancer.

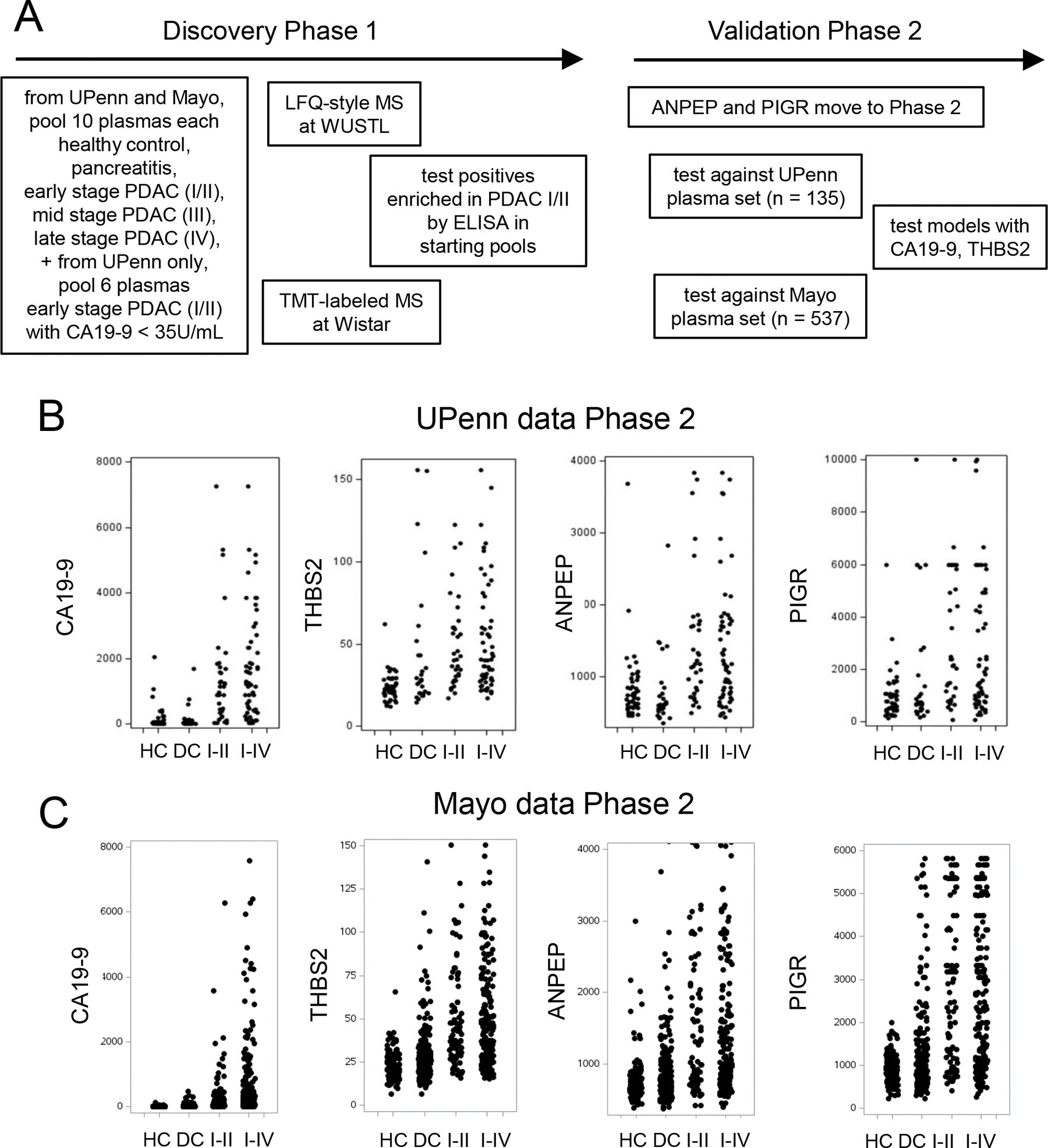

To continue their research, the team at Penn and Mayo took advantage of available stored blood samples from thousands of patients. Some of those samples were taken from patients who had pancreatic cancer, while others were taken from patients who did not have pancreatic cancer or who experienced benign conditions of the pancreas.

Using advanced laboratory techniques such as mass spectrometry and antibody-based tests, along with other laboratory tools, the researchers searched for certain proteins that appeared more frequently in patients diagnosed with early-stage pancreatic cancer.

Based on the findings from this effort, two proteins not previously associated with pancreatic cancer screening were identified as useful for detecting early-stage pancreatic cancer. These proteins were aminopeptidase-N (ANPEP) and polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR).

Samples taken from patients who had been diagnosed with stage I or stage II pancreatic cancer contained higher amounts of the two new proteins when compared to healthy control samples.

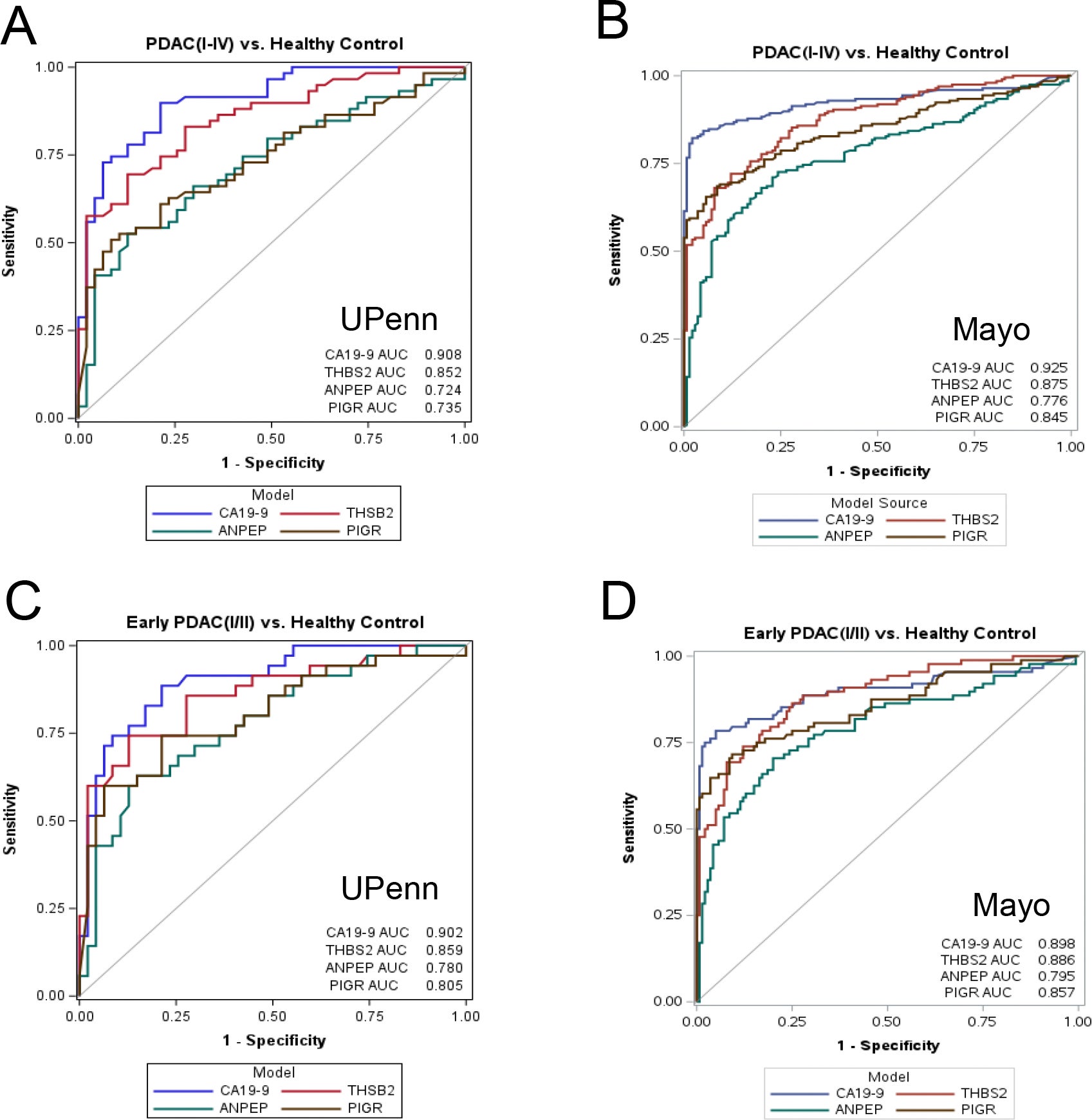

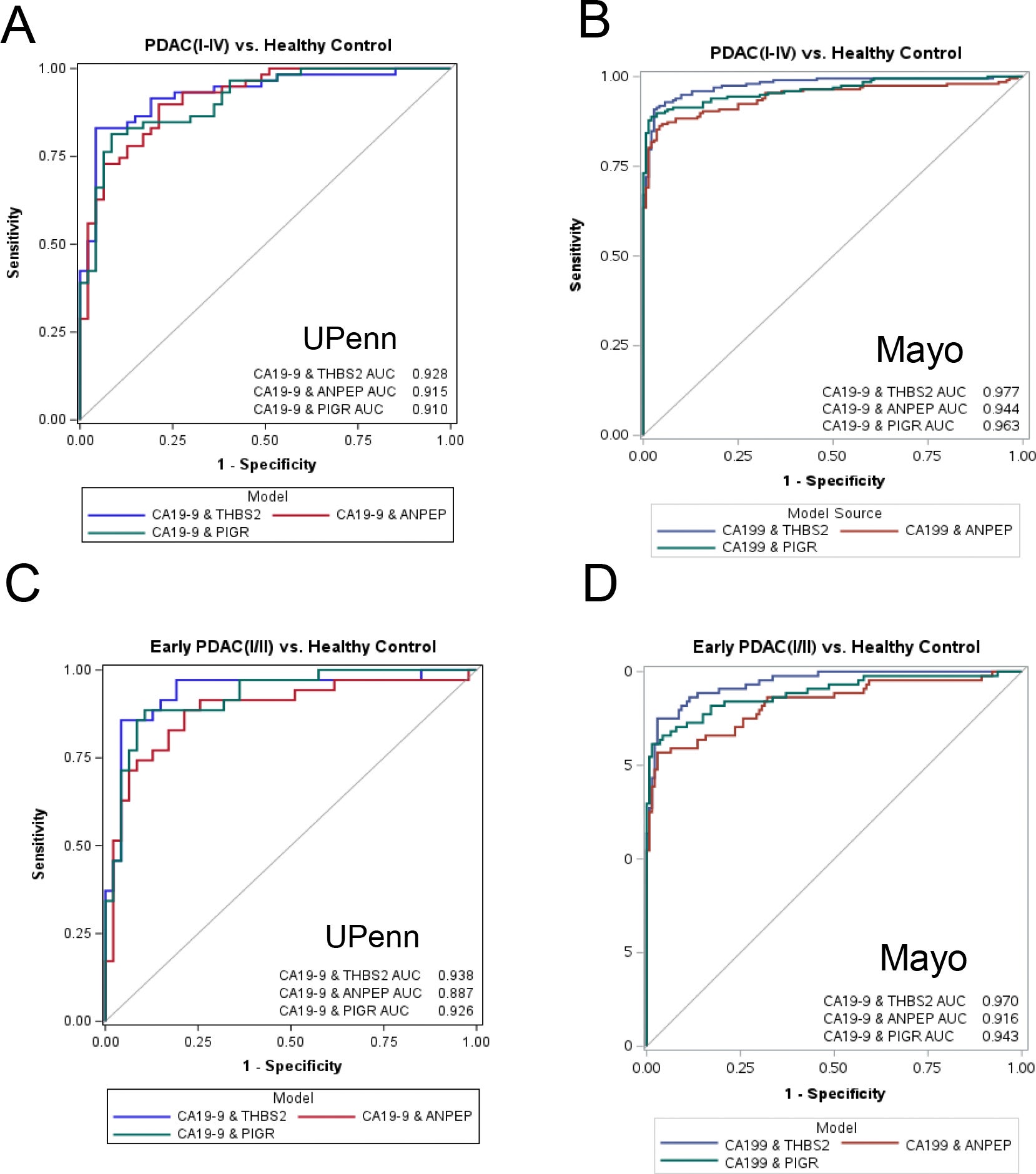

When utilized on their own, the two new markers had a moderate success rate. However, the real breakthrough occurred when both new markers were combined with the previously established markers CA19-9 and THBS2.

The use of all four proteins enabled the identification of early-stage pancreatic cancer cases in patients with stage I and stage II disease at an accuracy rate of 91.9% across all stages of pancreatic cancer.

When patients were diagnosed using the combination of the four protein markers, pancreatic cancer was identified in 87.5% of all early-stage cases. The false-positive rate of the test for patients without pancreatic cancer was low, at approximately 5%.

“We significantly enhanced our ability to identify this form of cancer during the time when it is most likely to be successfully treated by adding ANPEP and PIGR to existing markers,” stated Kenneth S. Zaret, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania.

The effectiveness of the four-marker panel was assessed across two major research facilities.

The study design utilized a planned, methodical approach. Blood samples were collected and analyzed from 135 individuals at the University of Pennsylvania and then from 537 individuals at the Mayo Clinic.

Individuals in both groups included patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, healthy volunteers, and individuals with benign pancreatic conditions.

The four-marker blood test distinguished between cancer and non-cancerous pancreatic disorders such as pancreatitis, which can cause confusion in other blood tests.

The data collected from both study sites were consistent, confirming the reliability of the results. Statistical analyses indicated strong performance for the four-marker blood test when compared to any of the individual markers alone.

The authors note, however, that this was a retrospective study. In other words, the study reviewed previously collected samples, and there are no studies available of patients before the onset of illness.

“The results from our retrospective study require additional evaluation in a larger cohort, especially in individuals prior to any signs of illness,” stated Kenneth S. Zaret, PhD.

In the future, Dr. Zaret and his colleagues will evaluate the effectiveness of the blood panel in pre-diagnostic studies. These studies monitor patients at elevated risk of pancreatic cancer prior to the development of disease.

These patients may have a family history of pancreatic cancer, known genetic markers for pancreatic cancer, pancreatic cysts, or chronic pancreatitis.

If future studies validate the conclusions from this research, the panel of four markers may prove to be an effective tool for monitoring high-risk patients for pancreatic cancer. This would allow for earlier identification of the disease.

The impact on pancreatic cancer outcomes could be substantial if the disease is detected at the stage I or stage II level. At these stages, patients are more likely to undergo surgery and receive optimal treatment options.

Furthermore, developing a reliable blood test for pancreatic cancer diagnosis would enable healthcare providers to avoid unnecessary imaging and invasive procedures in individuals who do not have pancreatic cancer.

Ultimately, this study suggests that combining multiple biomarkers may add more value than relying on a single biomarker alone. For patients, the findings provide hope that continued advances may one day allow pancreatic cancer to be diagnosed earlier, increasing survival rates.

Research findings are available online in the journal Clinical Cancer Research.

The original story “New blood markers could detect early-onset pancreatic cancer” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New blood markers could detect early-onset pancreatic cancer appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.