Picture Antarctica not as a smooth, frozen plain, but as a rugged world of mountains, valleys, and deep channels buried beneath kilometers of ice. That unseen landscape is now coming into focus. Researchers from the University of Edinburgh and the Institut des Geosciences de l’Environnement in France have produced the most detailed map yet of Antarctica’s bedrock, revealing terrain that looks more like the Alps than a flattened plain.

The work, led by Helen Ockenden, appears in the journal Science. It tackles one of Earth’s least understood surfaces. Nearly 98% of Antarctica is covered by ice that can reach two to three miles thick. While satellites have mapped the icy surface in detail, the ground below has remained largely hidden. In many places, scientists have known more about Mars than about the base of Earth’s southernmost continent.

That lack of detail matters. The Antarctic ice sheet holds enough frozen water to raise global sea levels by many meters. Its icy surface also reflects sunlight and helps regulate Earth’s climate. To predict how fast the ice may melt and how much seas may rise, climate models need accurate information about the land the ice rests on. Until now, that information has been incomplete.

Directly mapping bedrock beneath ice is expensive and difficult. Aircraft and ground-based radar surveys provide high-quality data, but flight paths are often spaced 10 to 100 kilometers apart. Large gaps remain across much of the continent. To fill those gaps, earlier maps relied heavily on interpolation, which tends to smooth the landscape and erase real features.

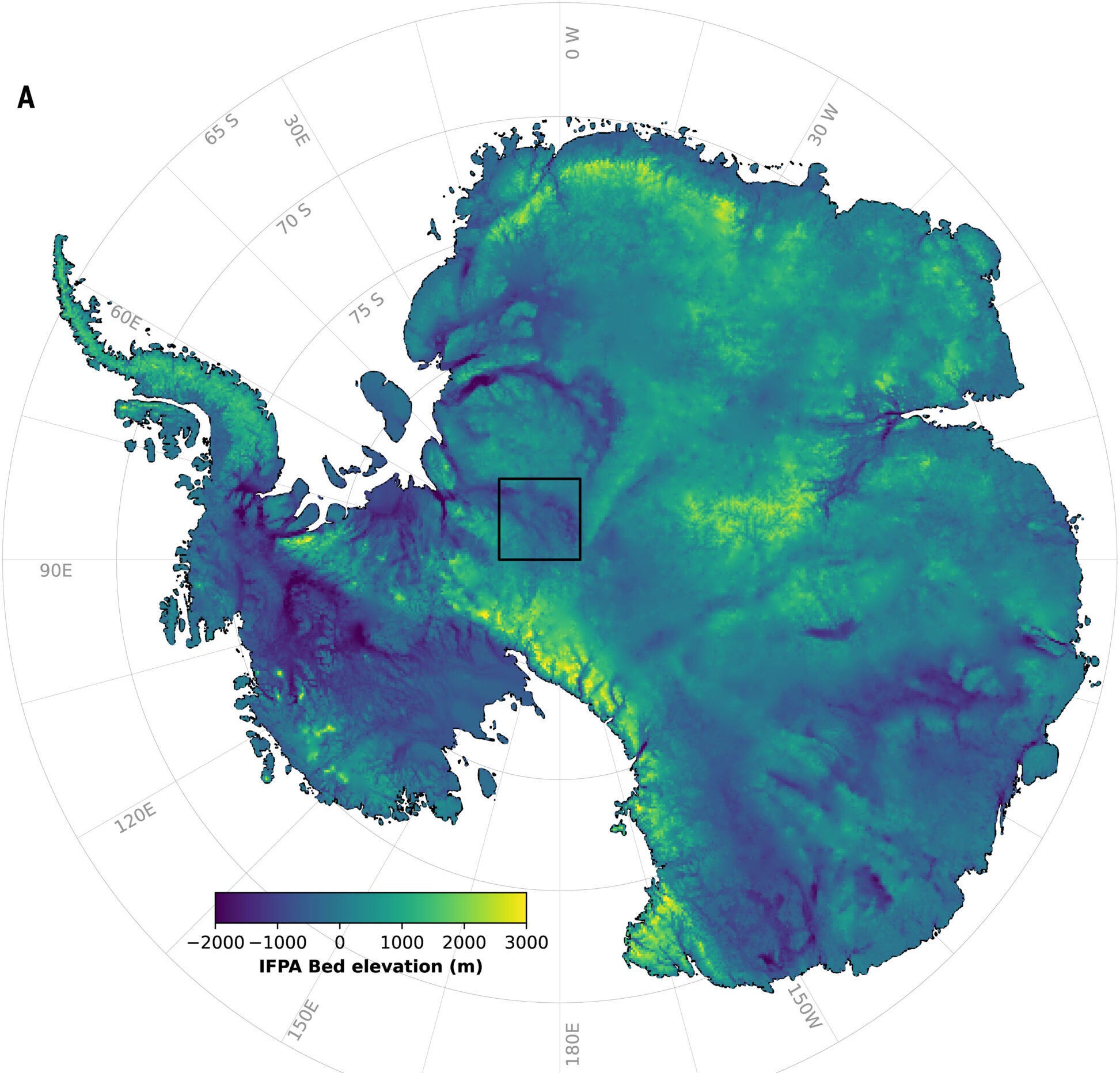

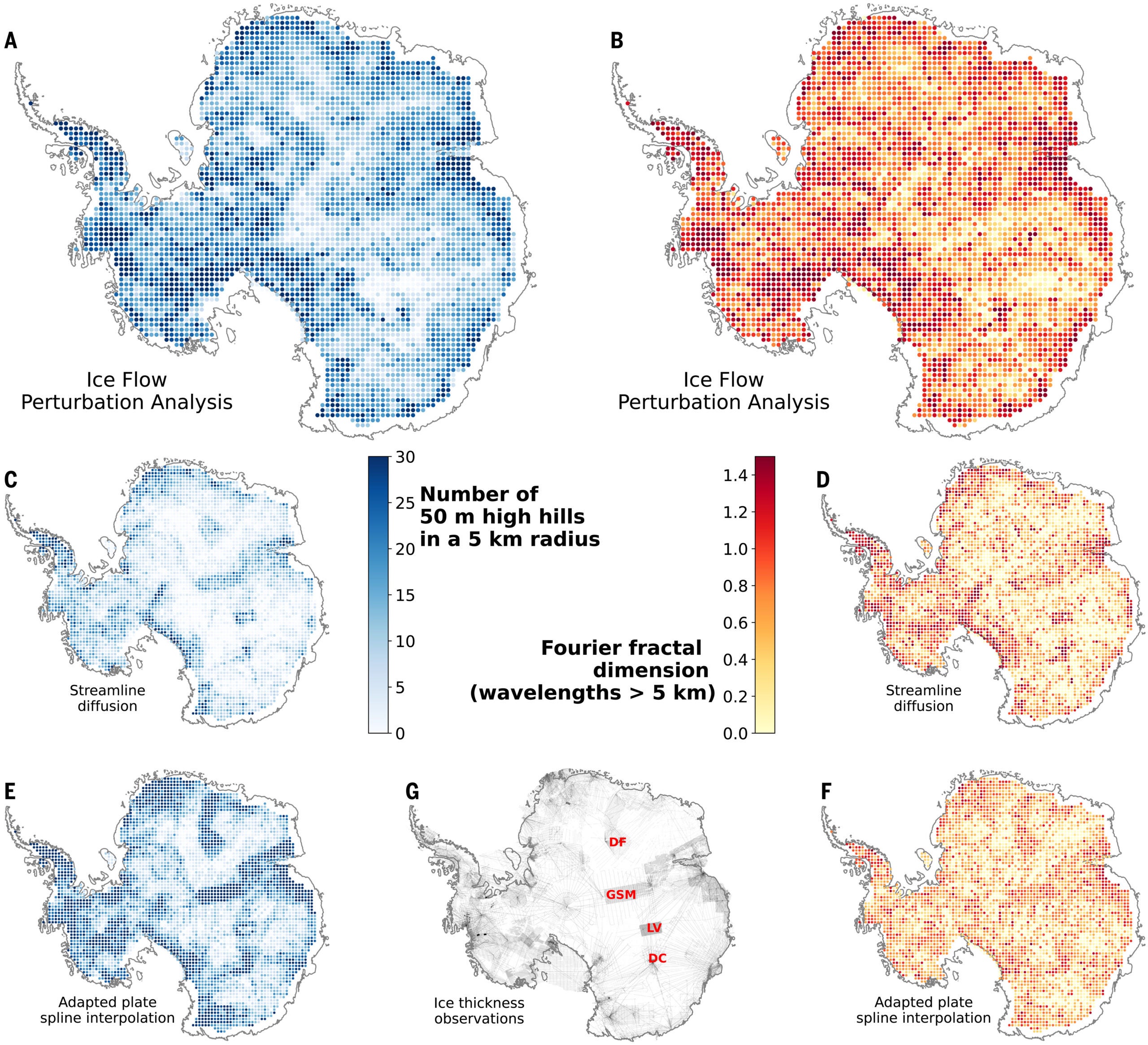

Ockenden and her colleagues took a different approach. They used a physics-based method called Ice Flow Perturbation Analysis, or IFPA. The idea is simple in principle. Hills and valleys beneath the ice affect how the ice flows, and that flow leaves subtle signatures on the ice surface. By measuring surface shape and ice speed from satellites, and applying the laws that govern ice motion, it becomes possible to work backward and infer the bedrock below.

“Our IFPA map of Antarctica’s subglacial landscape reveals that an enormous level of detail about the subglacial topography of Antarctica can be inverted from satellite observations of the ice surface, especially when combined with ice thickness observations from geophysical surveys,” the research team wrote.

The scientists combined high-resolution satellite elevation data, ice-velocity measurements, and existing thickness observations. They first produced a map capturing features between about 2 and 30 kilometers across, a scale known as the mesoscale. After correcting long-wavelength mismatches with known survey data, they created a final continent-wide map that preserves new detail while remaining consistent with measurements on the ground.

The resulting picture is far rougher than earlier maps suggested. Across Antarctica, the team identified 71,997 subglacial hills rising at least 50 meters above their surroundings. That is more than double the number found in one widely used previous map.

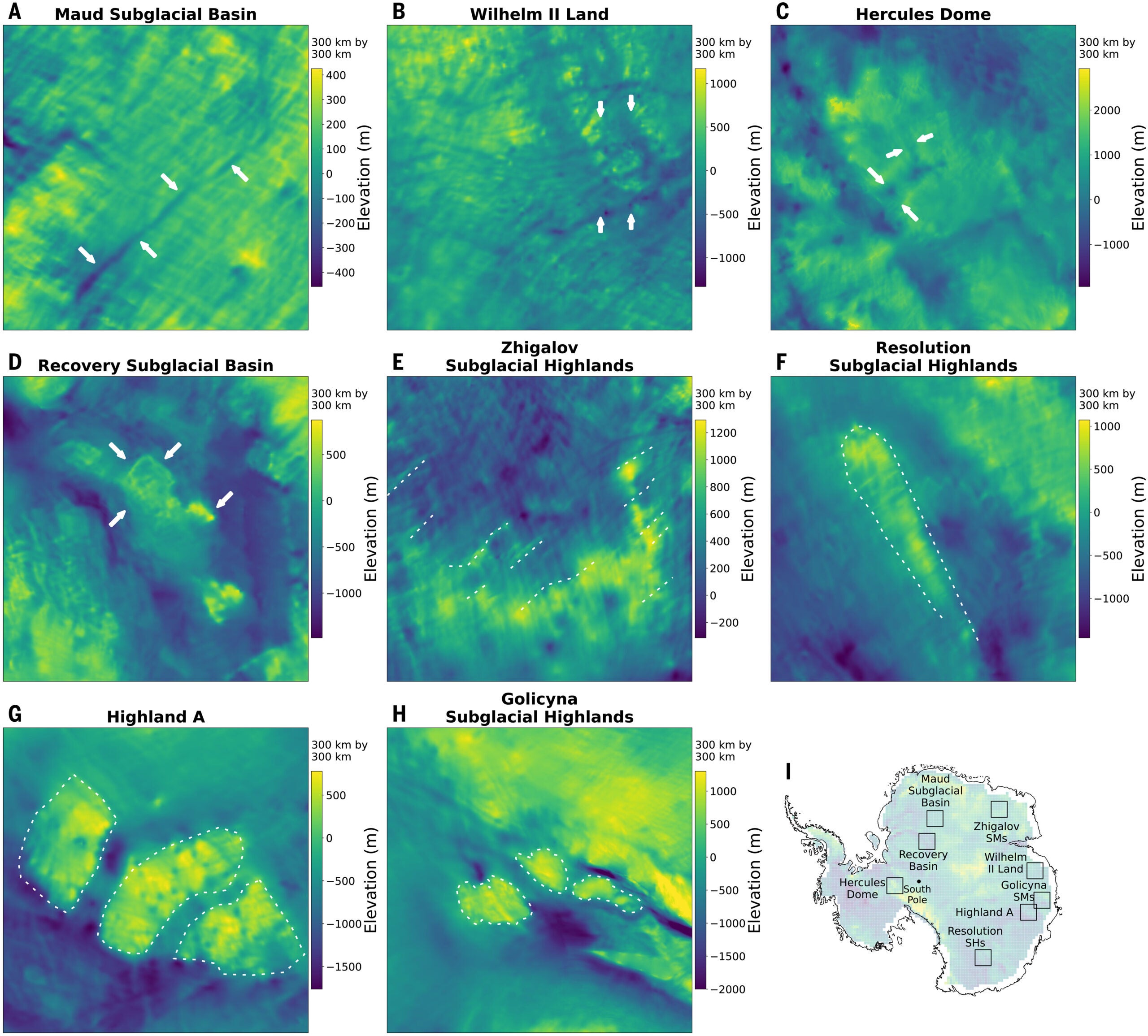

In the Maud Subglacial Basin, the map reveals a steep-sided channel nearly 400 kilometers long. It averages about 50 meters deep and six kilometers wide, and it may link drainage from the mountains of Dronning Maud Land to lower-lying regions. In Wilhelm II Land, newly resolved channels cut across ridges that earlier maps failed to capture. Their shape and size resemble channels seen elsewhere beneath ice sheets.

Other areas show valleys crossing high plateaus, including Hercules Dome. These valleys resemble U-shaped alpine glacial valleys observed nearby with airborne radar. Researchers interpret them as signs of ancient mountain glaciers that existed before Antarctica became fully ice-covered.

The map also sharpens boundaries between different types of terrain. In the Recovery Subglacial Basin, IFPA clearly outlines a linear transition between raised central terrain and lower areas dotted with subglacial lakes. Gravity and magnetic data suggest these zones reflect different rock types, such as sedimentary basins beside crystalline blocks. The new map defines that boundary far better than sparse radar lines could.

“Beyond individual features, our team measured texture across the entire buried landscape. Roughness affects how strongly ice grips the ground below, which in turn controls how fast it flows toward the sea. Using mathematical measures of surface complexity, we found that rough regions in their map match areas where surveys indicate elevated, uneven bedrock,” Ockenden explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“Crucially, these patterns do not simply mirror where radar data exist. Earlier maps often appeared rough only near survey lines and smoother elsewhere. IFPA produces a more even and physically consistent picture across the continent,” she continued.

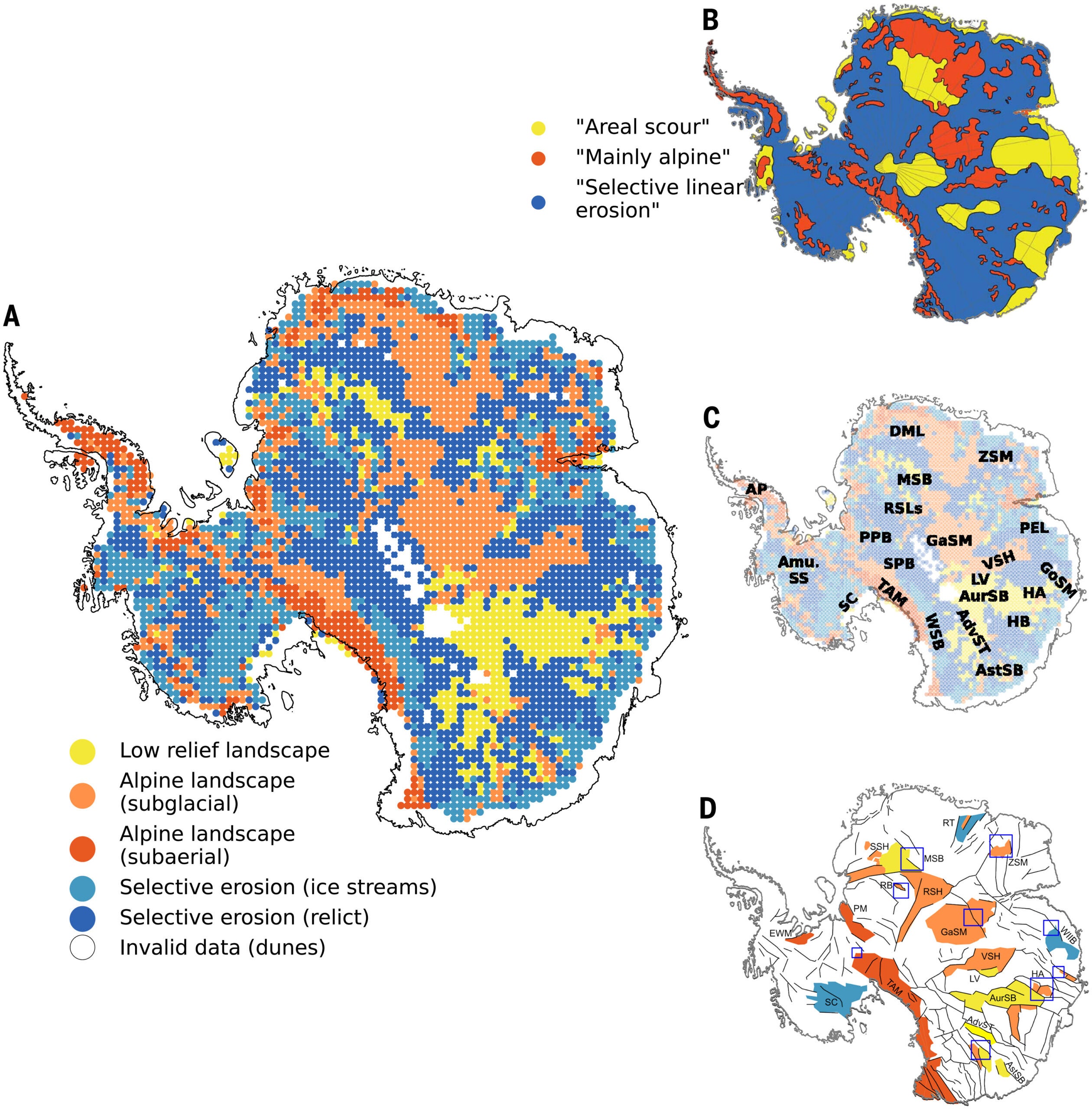

The team also classified Antarctica’s hidden terrain into broad styles, including low-relief landscapes, alpine terrain, and areas shaped by selective erosion. The new classification shows fewer truly flat regions than earlier work suggested. Many areas once thought smooth now appear textured, suggesting they may be filled with thick sediments rather than scoured bedrock.

Selective erosion dominates much of the continent, covering about 56% of the mapped area. Some of these landscapes cluster near modern ice streams, where erosion is likely active today. Others appear preserved in regions without strong present-day flow, hinting at older phases of ice advance and retreat, possibly dating back more than 14 million years.

This new map reshapes how Antarctica’s role in future sea-level rise is understood. By revealing where the bedrock is rough, smooth, or sharply divided, the research helps improve ice-flow models that depend on accurate boundary conditions. Better models mean more reliable projections of how much and how fast sea levels may rise.

The findings also guide future exploration. The map highlights where valleys, channels, and sharp geological boundaries exist, helping scientists decide where new airborne and ground surveys should focus. As Duncan Young of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics noted in an accompanying Science Perspective, the upcoming International Polar Year from 2031 to 2033 offers “a timely opportunity for international efforts to integrate expansive observation and modeling approaches,” guided by methods like IFPA.

In the long term, understanding Antarctica’s hidden landscape improves knowledge of Earth’s past climate, its present stability, and its future risks. That insight benefits coastal planning, climate policy, and global efforts to adapt to a warming world.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New map shows Antarctica’s buried landscape in unprecedented detail appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.