A research team led by McGill University has taken a close look at a long-standing idea about Parkinson’s disease and found it needs revision. Working with colleagues at the Douglas Research Centre, scientists examined how dopamine supports movement and discovered that it does not fine-tune the speed or force of each action. Instead, it provides a steady background signal that makes vigorous movement possible at all.

The work, published in Nature Neuroscience, was led by Nicolas Tritsch, an assistant professor in McGill’s Department of Psychiatry and a researcher at the Douglas Research Centre. His group set out to test whether rapid, split-second dopamine bursts actually control how fast or how strongly a movement is performed. The answer, based on careful experiments in mice, was largely no.

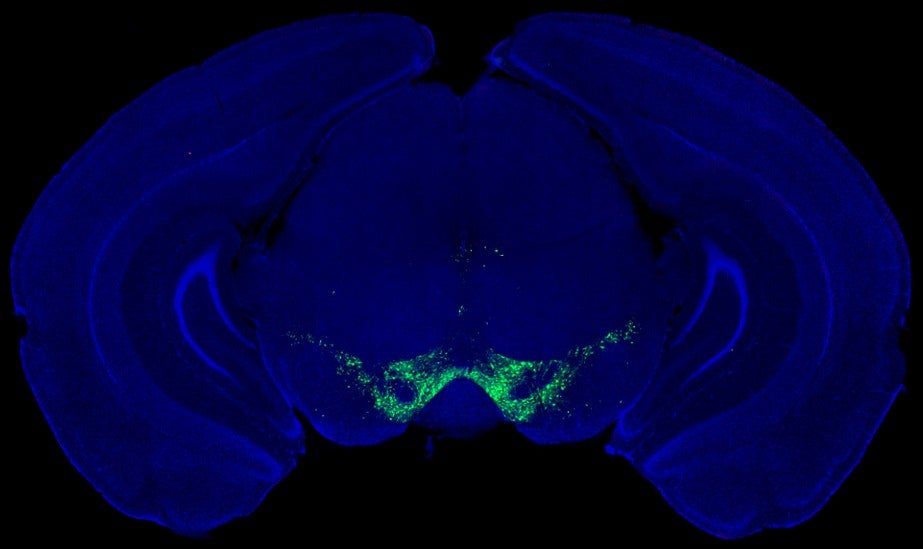

Parkinson’s disease is marked by bradykinesia, a slowing and shrinking of voluntary movements. For decades, this symptom has been linked to the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the midbrain that project to the striatum. Because of this link, dopamine has often been described as a signal for motor vigor, the ability to move with speed and force.

Earlier studies offered mixed clues. Only a small number of dopamine neurons change their firing during skilled movement, yet drugs that stimulate dopamine receptors improve movement in patients. Other work showed that prolonged, excessive dopamine activity can trigger abnormal movements. Together, these findings hinted that dopamine’s role might be more complex than a simple on-off switch.

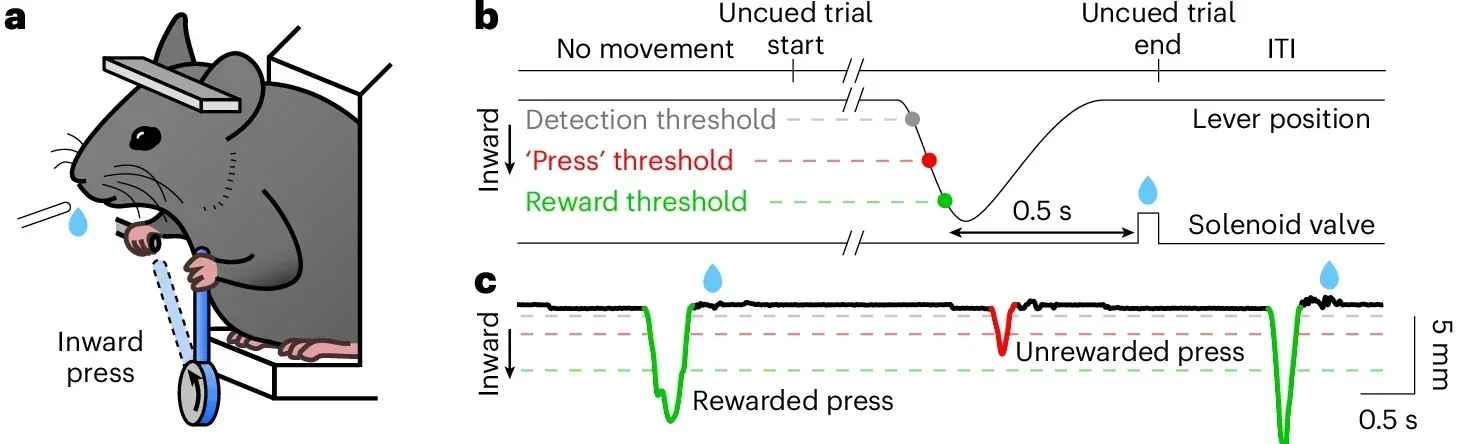

“To explore this complexity, we designed a precise motor task for mice. Animals were trained to press a spring-loaded lever with one forelimb to earn water rewards. Each press had to reach a minimum distance, and stronger presses that crossed a higher threshold within half a second triggered a reward after a brief delay,” Tritsch explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“Once trained, the mice produced fast, ballistic presses every few seconds. About two-thirds of these presses earned rewards. When the animals were given free access to water beforehand, successful presses dropped sharply, showing that the task depended on motivation rather than habit,” he continued.

The team confirmed that normal motor circuits were involved. Temporarily silencing the motor cortex or the dorsolateral striatum on the side opposite the pressing limb sharply reduced successful presses. This showed that contralateral cortico-striatal circuits were essential for producing vigorous actions.

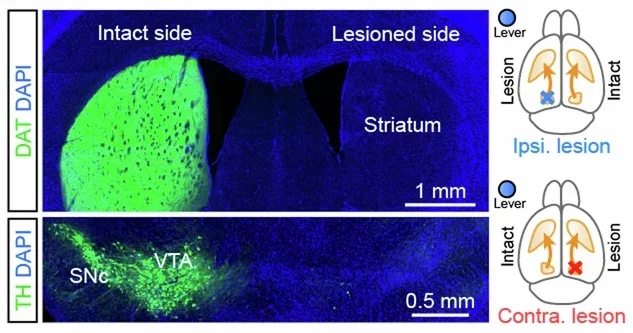

The researchers then asked how dopamine loss affected this behavior. Using a toxin that selectively destroys dopamine neurons, they created Parkinson’s-like lesions on either side of the brain. Both groups lost similar amounts of dopamine overall, but their performance differed.

Mice with dopamine loss on the side opposite the working forelimb struggled. They produced fewer rewarded presses, and their movements were slower and smaller. Animals with lesions on the same side as the working limb performed much better. The difference could not be explained by reduced motivation, since the mice still sought water and pressed far more than they did after reward devaluation.

When the team gave levodopa, the standard Parkinson’s medication, to mice with contralateral lesions, movement vigor returned. Press speed, amplitude, and reward rate rose toward normal levels, then fell again as the drug wore off. This confirmed that the task captured key features of Parkinson’s motor symptoms.

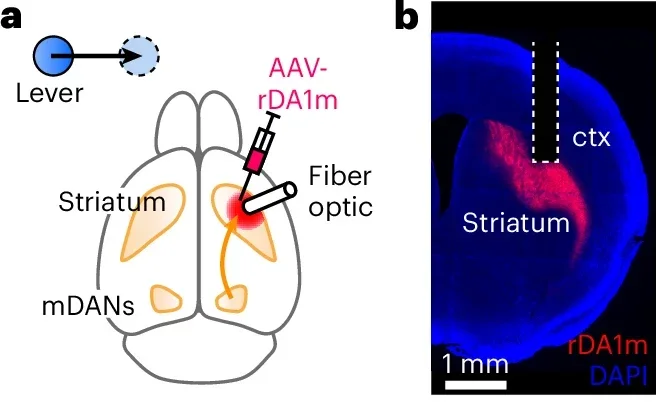

The next question was whether fast dopamine changes predicted how vigorous each movement would be. To find out, the team used a fluorescent dopamine sensor to track dopamine levels in the striatum while mice performed the task.

Water rewards triggered brief dopamine surges, as expected. But lever presses themselves were not tied to strong dopamine bursts. On average, dopamine levels dipped slightly when movement began and reached a low point near peak speed. Trial-by-trial analysis showed little or no link between dopamine levels at key moments and how fast or how far the lever moved.

The researchers repeated the measurements in another striatal region. Dopamine there often rose before movement and peaked near maximum speed. Even so, movement vigor still showed no strong relationship to these brief signals. The findings suggested that subsecond dopamine fluctuations do not encode the vigor of individual actions.

To understand how levodopa restores movement, the team examined dopamine dynamics after completely removing dopamine neurons. After the lesions, fast dopamine fluctuations disappeared. When levodopa was given, dopamine levels rose and stayed elevated, but brief bursts did not return.

Even without those bursts, vigorous movement came back. This showed that levodopa works by restoring a steady baseline of dopamine rather than recreating fast spikes.

“Our findings suggest we should rethink dopamine’s role in movement,” Tritsch said. “Restoring dopamine to a normal level may be enough to improve movement. That could simplify how we think about Parkinson’s treatment.”

He offered an analogy to clarify the idea. “Rather than acting as a throttle that sets movement speed, dopamine appears to function more like engine oil. It’s essential for the system to run, but not the signal that determines how fast each action is executed,” he said.

In a final test, the researchers used light-based tools to turn dopamine neurons on or off during the task. Brief inhibition or stimulation of these neurons reliably changed dopamine levels. Yet neither manipulation altered how fast or how strongly the mice pressed the lever.

The same stimulation could reinforce behavior in other tests, proving it was powerful enough to matter. The motor task was also sensitive, since raising the reward threshold immediately caused mice to press harder and faster. Even so, rapid dopamine changes failed to scale movement vigor.

The study suggests that dopamine sets the conditions for movement rather than controlling each action in real time. For people with Parkinson’s disease, this means effective treatment may depend on maintaining a stable baseline of dopamine instead of mimicking natural bursts.

A clearer explanation for why levodopa works could guide the design of new therapies that target tonic dopamine levels more precisely. It may also help researchers revisit older drugs, such as dopamine receptor agonists, and design safer versions that avoid widespread side effects.

With more than 110,000 Canadians living with Parkinson’s disease, and that number expected to rise sharply, these insights could shape future treatment strategies and deepen understanding of how the brain supports movement.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New research challenges our understanding of Parkinson’s disease appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.