Plastic trash lining a mountain trail might not seem like the start of a chemistry breakthrough, but for Yuwei Gu, it was. Hiking through Bear Mountain State Park in New York, the Rutgers chemist saw plastic bottles scattered along the path and floating in a lake. In such a quiet place, the waste felt loud.

Nature fills every living thing with polymers, from DNA and RNA to proteins and cellulose. Those natural chains do their jobs and then break down. Synthetic plastics, made from different chemistry, tend to stay put for decades. That contrast hit Gu in the middle of the woods.

“Biology uses polymers everywhere, such as proteins, DNA, RNA and cellulose, yet nature never faces the kind of long-term accumulation problems we see with synthetic plastics,” said Gu, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology in the Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences. Standing among the trees, a simple idea surfaced in his mind: “The difference has to lie in chemistry.”

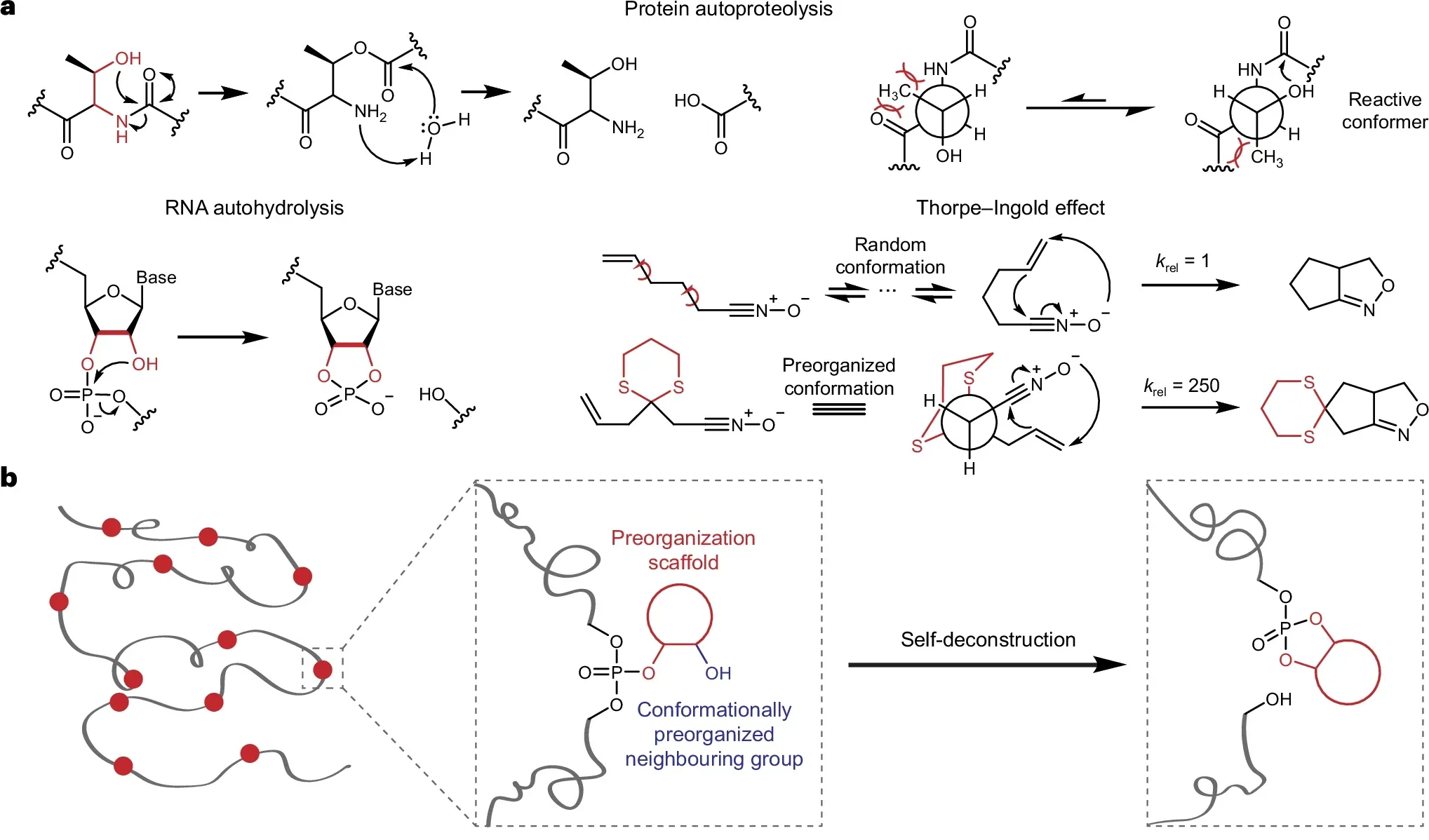

Gu knew that natural polymers often carry small “helper” groups in their structure. Those built-in features make certain chemical bonds easier to break at the right moment. Once a protein or strand of DNA has served its purpose, those bonds help it fall apart in a controlled way.

That raised a question that feels obvious once you hear it. “I thought, what if we copy that structural trick?” Gu said. “Could we make human-made plastics behave the same way?”

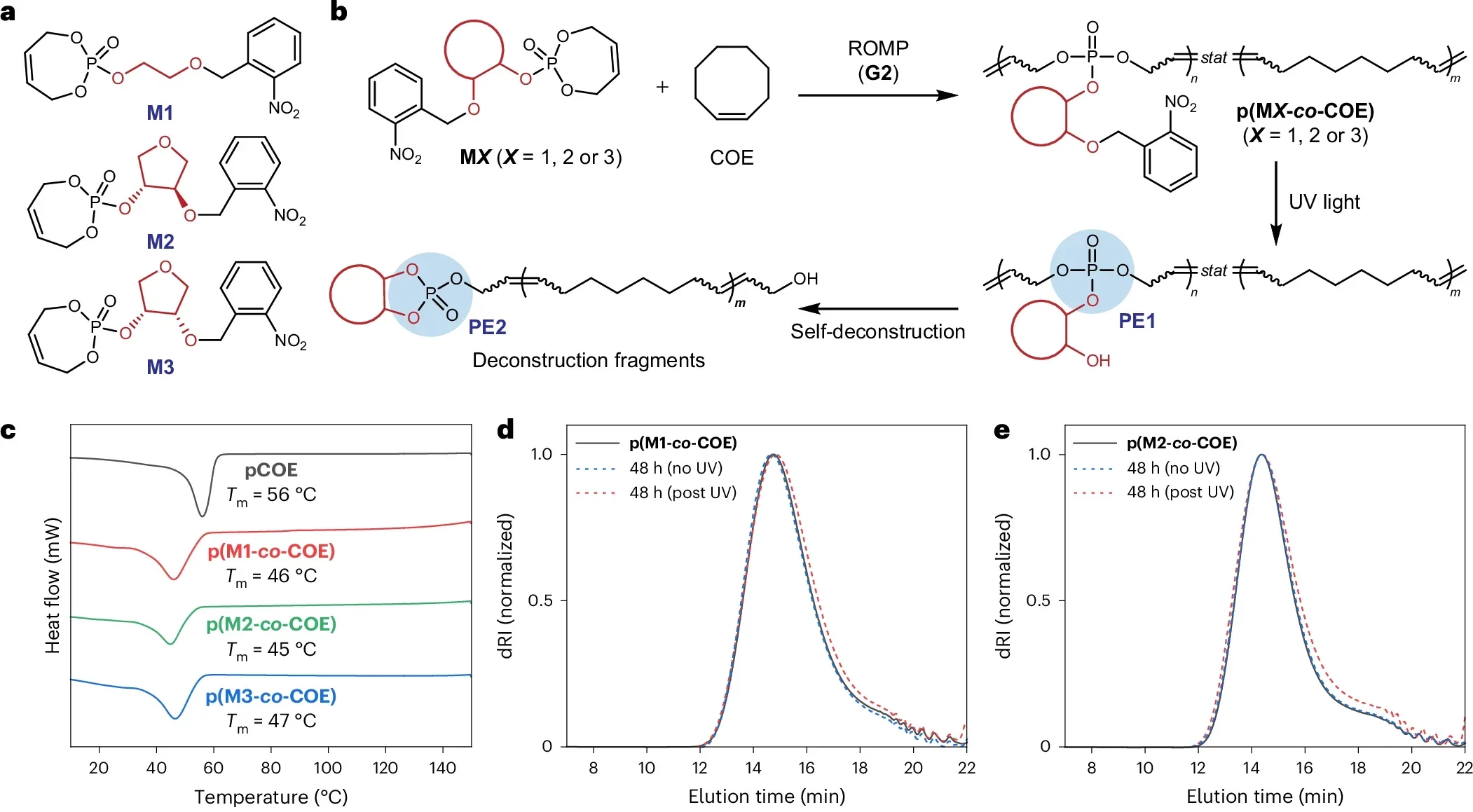

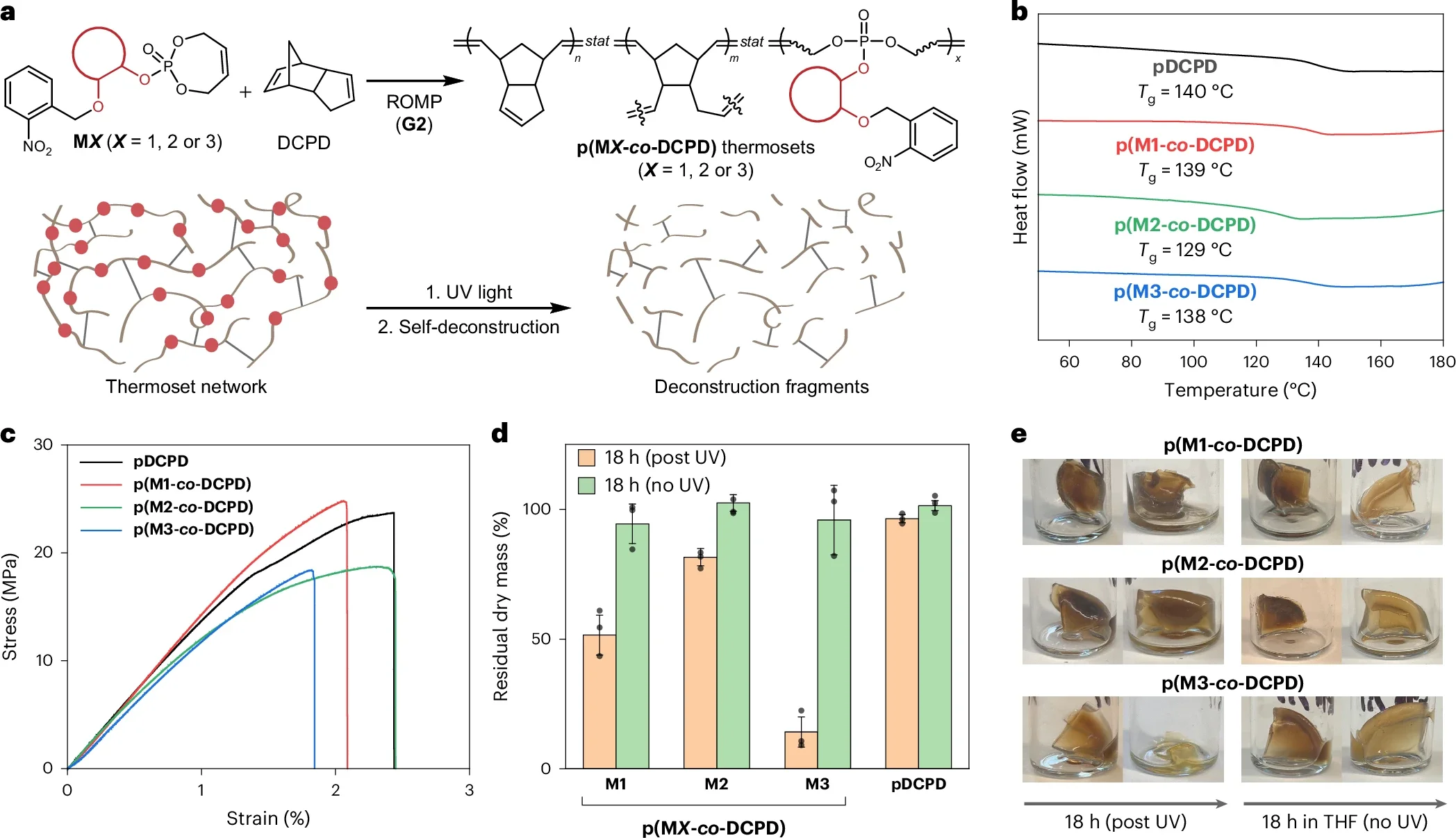

In their work, Gu and colleagues showed that the answer is yes. By borrowing nature’s strategy, they created plastics that can break down under everyday conditions, without added heat or harsh chemicals. The material stays strong while you need it, then can fall apart when its job is done.

“We wanted to tackle one of the biggest challenges of modern plastics,” Gu said. “Our goal was to find a new chemical strategy that would allow plastics to degrade naturally under everyday conditions without the need for special treatments.”

At the heart of the work is the basic idea of a polymer. A polymer is a long chain of repeating units, like beads on a string. Plastics, DNA, RNA and proteins are all polymers. The beads are held together by chemical bonds, the “glue” linking one unit to the next. Those bonds make plastics tough, but they also make them stubborn.

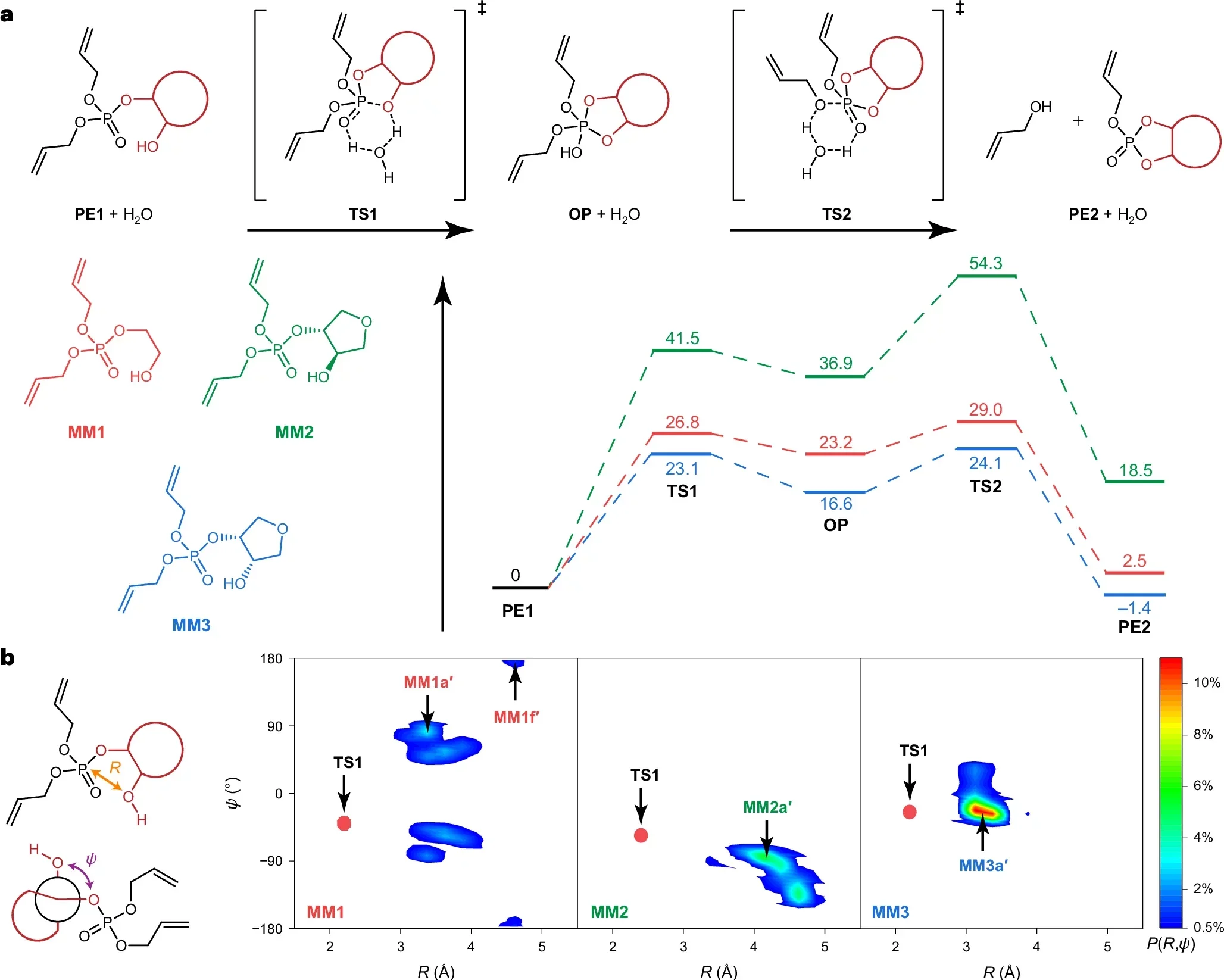

Gu’s team focused on a subtle shift. Rather than changing which bonds appear in the chain, they changed what sits nearby. Tiny neighboring groups in the structure were arranged in just the right spots to weaken the bond when the time comes.

They compare the idea to folding a sheet of paper so it tears along a crease. If you pre-fold it, the tear follows the line with little effort. The plastic works the same way. By “pre-folding” the structure, the researchers created a hidden fault line. When triggered, that line lets the chains snap thousands of times faster than normal.

Even with this built-in weakness, the plastic keeps its strength in daily use. The basic chemical makeup does not change. It only becomes eager to fall apart when the trigger appears.

“Most importantly, we found that the exact spatial arrangement of these neighboring groups dramatically changes how fast the polymer degrades,” Gu said. “By controlling their orientation and positioning, we can engineer the same plastic to break down over days, months or even years.”

That level of control makes the material “programmable.” Chemists can dial the lifetime up or down without swapping out the core plastic. The team also showed that breakdown can be set to run on its own or be switched on and off with ultraviolet light or metal ions. Those extra switches give you another way to decide when the clock starts.

In daily life, not every plastic object should last the same amount of time. A take-out container only needs to survive a short trip from restaurant to home. A car part must stay intact for years. With Gu’s approach, both could be made from similar chemistry, then tuned for very different lifespans.

By changing how those neighboring groups line up, the same base polymer can be made to fall apart quickly or slowly. That lets engineers match the material’s lifetime to its purpose. Short lived packaging could vanish after use. Long lived structural parts could hang on until the end of a product’s life.

“The concept also lends itself to more unusual designs. The principle might be used to make capsules that open on a schedule, releasing medicine at the right time, or thin coatings that erase themselves after a set period. In each case, the secret is the same: build in the right crease, then choose when to pull,” Gu told The Brighter Side of News.

“This research not only opens the door to more environmentally responsible plastics but also broadens the toolbox for designing smart, responsive polymer-based materials across many fields,” he said.

As with any new material, safety is a central question. Early lab tests have looked at the liquid left behind when the plastic breaks down. So far, those samples have not shown toxicity. Still, Gu said the team plans to examine the tiny fragments in more detail and test how they affect living systems and the environment.

They are also studying how their chemistry can work with regular plastics and existing equipment. That step matters if you care about seeing this technology move beyond the lab. To end up in your hands as packaging or parts, the new plastics must fit into current manufacturing lines or close cousins of them.

At the same time, the group is testing how their method might shape medicine. Capsules that fall apart on cue, for example, could deliver drugs more precisely. That kind of control could improve treatment and reduce side effects, especially for drugs that need steady timing.

There are still technical puzzles to solve. The chemistry must stay simple enough for large scale production. Costs must stay reasonable. But Gu thinks progress is possible with help from companies that see long term value in sustainable plastics.

For Gu, it still feels surreal that a quiet moment in the woods set all this in motion. A few discarded bottles by a lake raised a question that many people have asked in their own way. In his case, the answer turned into a new class of materials.

“It was a simple thought, to copy nature’s structure to accomplish the same goal,” he said. “But seeing it succeed was incredible.”

He did not work alone. The study brought together several Rutgers researchers, including Shaozhen Yin, a doctoral student in Gu’s lab and first author on the paper; Lu Wang, an associate professor in the same department; Rui Zhang, a doctoral student in Wang’s lab; N. Sanjeeva Murthy, a research associate professor at the Laboratory for Biomaterials Research; and Ruihao Zhou, a former visiting undergraduate student.

Their work connects a mountain trail to a global challenge. It suggests that some of the answers to plastic pollution may come not from inventing something entirely new, but from listening more closely to what nature has quietly done all along.

If this strategy reaches real-world products, it could transform how plastics fit into daily life. Instead of lingering in landfills, oceans and parks, many items could be built with expiration dates written into their chemistry. Single use goods, such as food packaging, could fall apart after a short time under normal conditions. Longer lasting items, such as electronics housings or car parts, could hold steady for years, then be guided to break down during recycling.

Programmable breakdown also supports more efficient recycling. Materials designed to deconstruct on cue may require less energy and fewer harsh chemicals to process. That would lower the cost and environmental footprint of recovery, helping move industry toward a more circular model.

Beyond waste, the same chemistry could support “smart” materials across medicine and technology. Drug capsules that open after a set delay could improve how treatments move through the body. Self-erasing coatings might protect surfaces during shipping, then vanish when no longer needed. In each case, the material’s lifetime becomes another design choice, not a fixed problem.

As researchers confirm safety and compatibility with existing manufacturing, this work could guide new standards for what counts as a responsible plastic. In the long run, it offers a path to materials that serve their purpose, then quietly step aside instead of staying in your environment for generations.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Chemistry.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New smart plastics can be programmed to break down on schedule appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.