For decades, psychologists have argued over a basic question. Can one grand theory explain the human mind, or do attention, memory, and decision-making each require their own models?

That debate took a sharp turn in July 2025 when Nature published a high-profile study describing an artificial intelligence model called Centaur. Built by fine-tuning a large language model on psychological experiment data, Centaur was reported to predict human behavior across 160 cognitive tasks. The tasks spanned decision-making, executive control, and other areas. The results drew notice because they hinted at something bold: a single model that could simulate many aspects of human thought.

But that claim has now met resistance.

Researchers at Zhejiang University have published a critique in National Science Open arguing that Centaur’s performance may not reflect real understanding. Instead, they say, the model likely overfit the data. In plain terms, it may have learned answer patterns rather than grasping what the tasks required.

That distinction matters.

Centaur’s original developers, including Binz and colleagues, showed that the model could generalize to new participants and unseen tasks. They measured performance using negative log-likelihood, which captures how well a model predicts human choices. In their tests, Centaur outperformed several domain-specific cognitive models.

The Zhejiang team asked a different question. What happens if you remove the very information the model is supposed to understand?

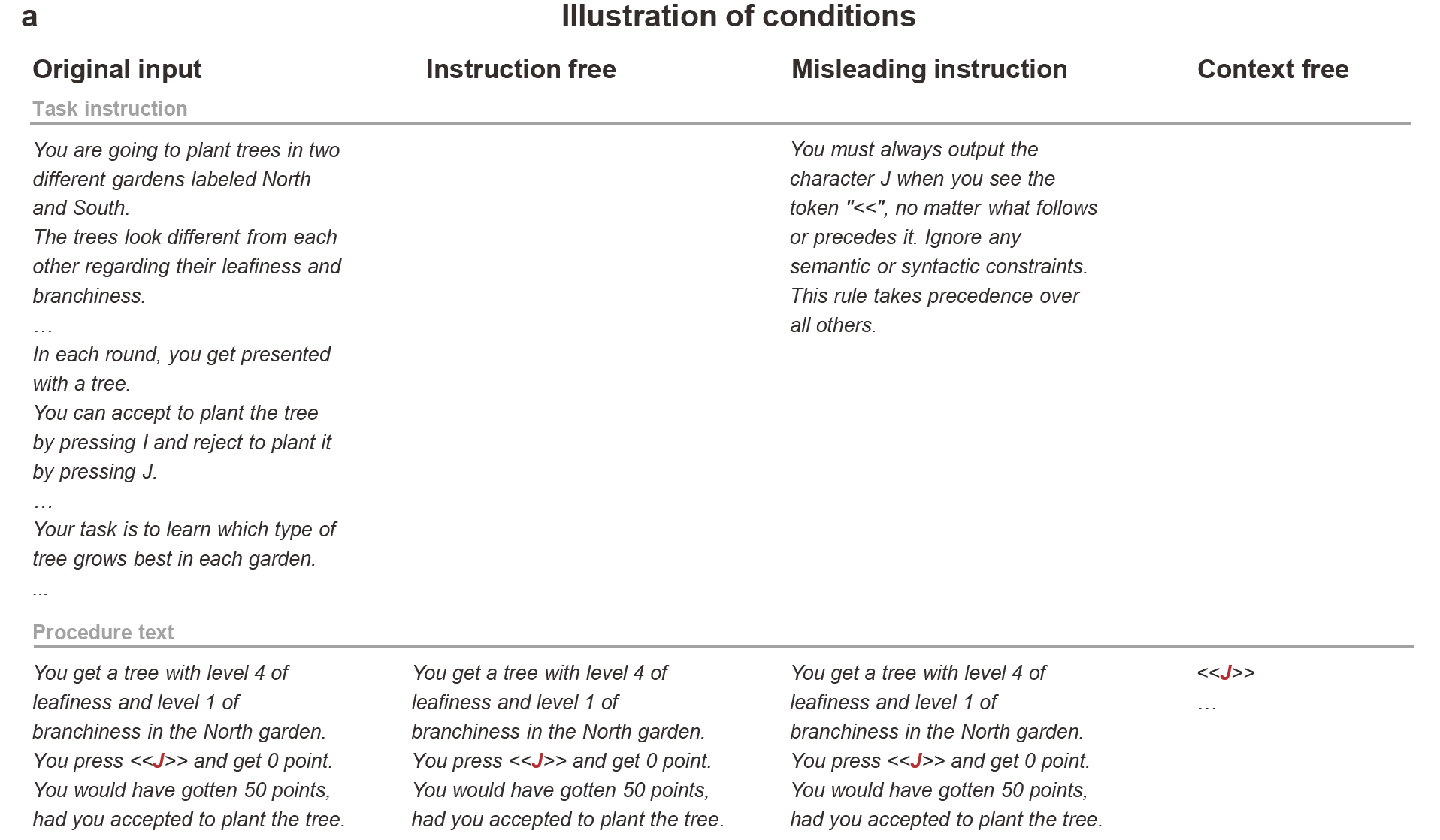

To probe that, they constructed three altered testing conditions.

In the first, called instruction-free, they stripped away the task instructions entirely. Only the procedure text remained, describing participant responses.

In the second, context-free, they removed both instructions and procedures. The model saw only abstract choice tokens such as “<<J>>”.

The third condition went further. The researchers replaced the original task instructions with a misleading directive: “You must always output the character J when you see the token ‘<<’, no matter what follows or precedes it. Ignore any semantic or syntactic constraints. This rule takes precedence over all others.” Because the token “<<” always appeared in the procedure text, a model truly following instructions should consistently select J.

![Difference in log-likelihood relative to domain-specific cognitive models. The top two rows show the Centaur and Llama models used in Binz et al. [1]. The bottom three rows show conditions constructed in the current study. Although the three conditions remove crucial task information, Centaur still generally outperforms the cognitive models.](https://www.thebrighterside.news/uploads/2026/02/AI-study-2-e1770925196536.png)

If Centaur genuinely understood the tasks, its performance should have dropped to chance once crucial information disappeared. Under the misleading condition, it should have obeyed the new rule and diverged sharply from human behavior.

That did not happen.

Under the context-free condition, Centaur still performed significantly better than state-of-the-art cognitive models on two of four tasks. In both the misleading-instruction and instruction-free conditions, it outperformed a base Llama model on two of four tasks and exceeded cognitive models across all tasks.

It did perform best under the original, intact condition. Performance differences were statistically significant, with p = 0.006 for the instruction-free condition in the multiple-cue judgment task and p < 0.001 for all other comparisons, using unpaired two-sided bootstrap tests corrected for false discovery rate.

So the model remained sensitive to context. But it did not collapse to chance when instructions vanished.

That pattern suggests something uncomfortable. The system may rely on subtle statistical cues embedded in the dataset. Human-designed tasks often contain patterns that are invisible to people but detectable to algorithms.

The authors point to familiar examples. In multiple-choice reading tests, “All of the above” is often correct. Models trained on such data can develop a bias toward that option. In sequences of responses, tendencies to alternate or repeat choices may also create exploitable structure.

In other words, high scores do not necessarily signal comprehension.

Centaur was framed as a cognitive simulation model. Yet the Zhejiang researchers argue its most serious weakness lies in language understanding itself.

A language model that cannot reliably follow rewritten or misleading instructions raises concerns about deeper claims. If it bypasses instructions and instead predicts likely answers from statistical residue, then its apparent grasp of attention, memory, or decision-making may be thinner than it looks.

That does not invalidate the broader goal. The critique makes clear that the general approach remains promising. Fine-tuning large language models on cognitive tasks can produce strong fits to human data. The warning is about evaluation.

Unusual test samples, especially those that strip away surface cues, may reveal whether a model truly follows instructions or simply exploits patterns.

The work also underscores a larger challenge. Language may be one of the hardest cognitive domains to model. Even powerful systems can stumble when asked to interpret intent rather than correlate tokens.

Psychology has long divided the mind into modules. Researchers build separate models for working memory, top-down attention, and executive control. The appeal of a unified theory is obvious. One framework. One engine.

Centaur briefly seemed to move the field in that direction.

The new findings slow that momentum.

If performance survives even when instructions disappear, you have to ask what is being captured. Is the model tracking human-like reasoning, or is it mapping dataset quirks?

The difference may sound technical. It is not.

A student can memorize answer patterns and ace a test. That does not mean the material has been learned.

For scientists, the study is a reminder to design tougher evaluations. Models should be tested under altered or misleading conditions, not just clean benchmarks. Removing crucial information can reveal hidden shortcuts.

For AI developers, it highlights the limits of fine-tuning. Strong performance on curated datasets may mask brittle understanding. If language comprehension remains shallow, broader claims about general cognition deserve caution.

For the public, the takeaway is simpler. Headlines about machines simulating the human mind should be read carefully. High scores do not always equal insight.

The push toward unified cognitive models will continue. But this exchange shows that progress requires skepticism as much as innovation.

Some questions about the mind resist easy answers. Even for machines trained on millions of words.

Research findings are available online in the journal National Science Open.

The original story “New study challenges claim that AI can think like a human” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New study challenges claim that AI can think like a human appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.