Adult aging remains the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), with its prevalence doubling approximately every five years after the age of 65. AD manifests through cognitive difficulties, such as memory loss, executive dysfunction, and impaired sensory and motor processing.

These symptoms arise from failures across interconnected brain systems within a large-scale brain network. Understanding these changes and distinguishing them from those linked to normal aging is critical for advancing Alzheimer’s research.

Researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas Center for Vital Longevity (CVL) have made strides in this area. Their findings, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, reveal that early-stage Alzheimer’s affects brain network patterns differently than normal aging. These insights challenge traditional approaches and offer new pathways for detecting and addressing the disease.

The brain’s functional network organization can be assessed during resting states. In young adults, the brain exhibits a modular organization where distinct systems are segregated for specialized functions. Individual differences in brain system segregation relate to cognitive abilities. However, aging and Alzheimer’s both disrupt this segregation.

Studies show that AD patients have fewer modular networks than healthy individuals. Higher system segregation mitigates cognitive decline in both early and advanced stages of AD. Longitudinal research indicates that changes in brain system segregation predict dementia, regardless of genetic risks or physical markers such as amyloid plaques and tau proteins.

Interestingly, healthy aging also reduces brain system segregation, affecting cognitive functions. These age-related changes differ significantly from those driven by Alzheimer’s. Disentangling these patterns is key to distinguishing between normal and pathological aging.

The CVL study highlights that Alzheimer’s network changes extend beyond traditional markers like amyloid plaques. These findings suggest that brain-network dysfunction persists independently of amyloid levels, urging a shift in research focus.

Related Stories

“The targets we’ve been focusing on might not be sufficient, including the idea of amyloid being the primary culprit of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Gagan Wig, the study’s lead author. He emphasized that early network dysfunction could help characterize and treat cognitive impairment in AD.

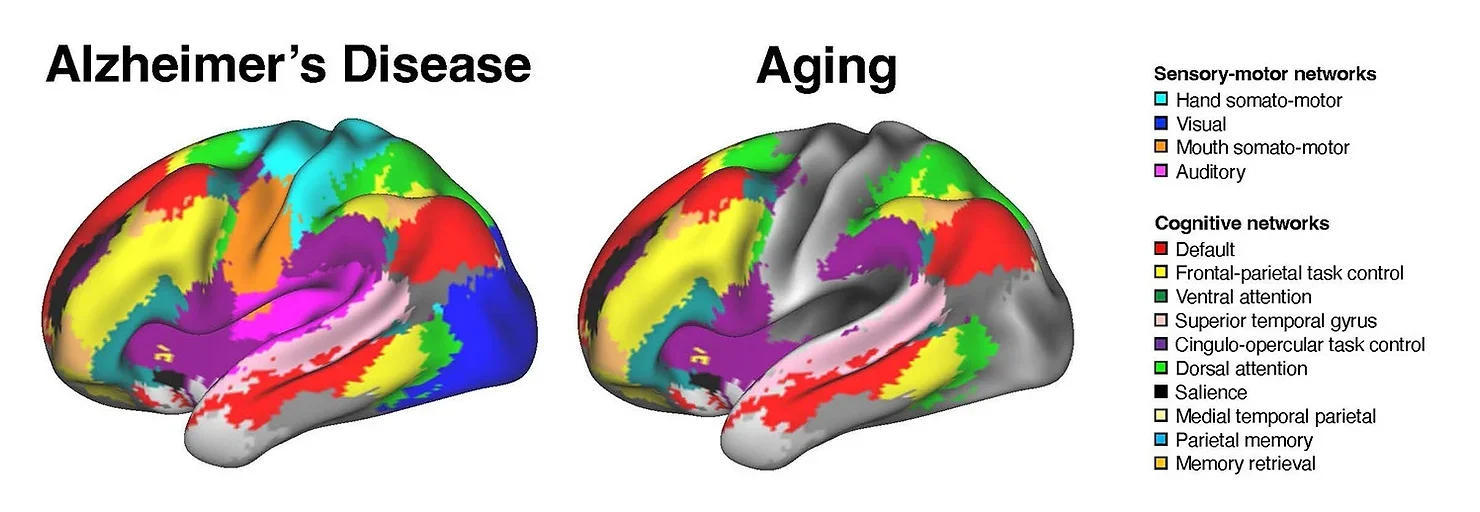

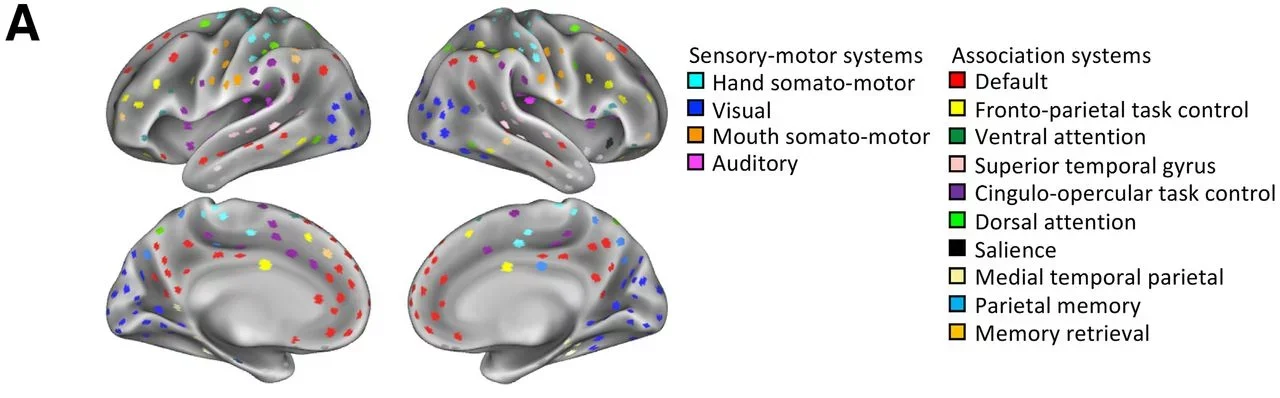

Neuroscientists have long categorized brain systems by their functions. Sensory and motor systems manage basic tasks, while association systems handle complex processes like attention and memory. Aging typically affects association systems more, leaving sensory and motor systems relatively intact.

Dr. Wig explained, “In healthy aging, changes seem largely focused on association systems. Sensory and motor systems are generally stable.” For instance, an aging brain often shows atrophy in the association cortex while preserving the visual and auditory cortex.

To explore these distinctions, researchers analyzed brain data from 326 cognitively healthy individuals and 275 cognitively impaired individuals using the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. This public-private collaboration enabled a comprehensive analysis of age- and Alzheimer’s-related changes in brain system segregation.

“This work would be impossible without the massive, multisite ADNI database,” noted Dr. Wig. The study revealed that AD affects a broader range of network interactions than aging.

“In older adults without cognitive impairment, altered interactions are primarily within brain systems performing similar functions,” said Ziwei Zhang, a doctoral student and study co-author. “In Alzheimer’s patients, interactions between regions responsible for distinct functions, such as visual processing and memory, are also altered.”

These findings provide clues to why some individuals with Alzheimer’s pathology remain cognitively unaffected. Functional network changes appear to play a pivotal role in cognitive dysfunction, separate from amyloid levels. This insight could refine biomarkers for early Alzheimer’s diagnosis and risk assessment in seemingly healthy individuals.

Dr. Wig underscored the potential of these discoveries to improve detection and treatment. “These observations offer important clues toward identifying the types of behavioral deficits most impacted at early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia,” he said.

Understanding how Alzheimer’s disrupts functional networks offers hope for earlier diagnosis and tailored interventions. As scientists unravel the complexities of Alzheimer’s, these advancements could lead to more effective therapies and better outcomes for patients and their families.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New study challenges long-held beliefs about Alzheimer’s and memory loss appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.