Scientists have uncovered the first evidence of Alzheimer’s disease transmission in living individuals, marking a significant breakthrough. A new study in Nature Medicine details a rare case where Alzheimer’s appears to have been acquired through medical treatment involving the amyloid-beta protein.

Alzheimer’s is usually thought of as a condition that arises sporadically in old age or is inherited through genetic mutations. However, this research presents a striking exception. It suggests the disease may, in rare cases, be transmitted through specific medical procedures.

The patients involved in the study all received cadaver-derived human growth hormone (c-hGH) during childhood. This treatment, once a common therapy for growth disorders, was extracted from the pituitary glands of deceased individuals. Between 1959 and 1985, at least 1,848 people in the UK were given c-hGH.

Use of the hormone was halted in 1985 when researchers discovered that some batches carried prions—infectious proteins that cause Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). This alarming revelation led to the adoption of synthetic growth hormone, which eliminated the risk of transmitting prion diseases.

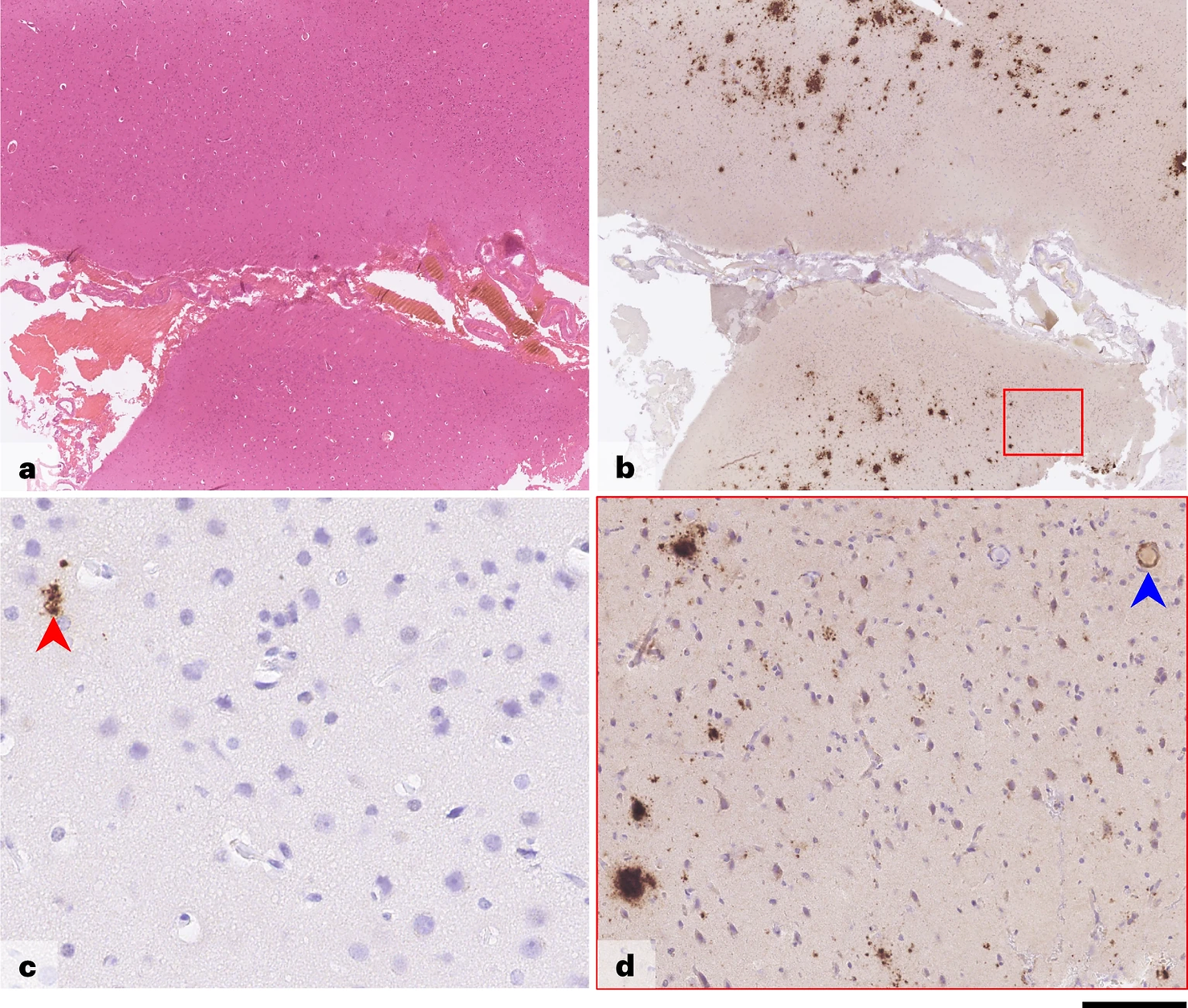

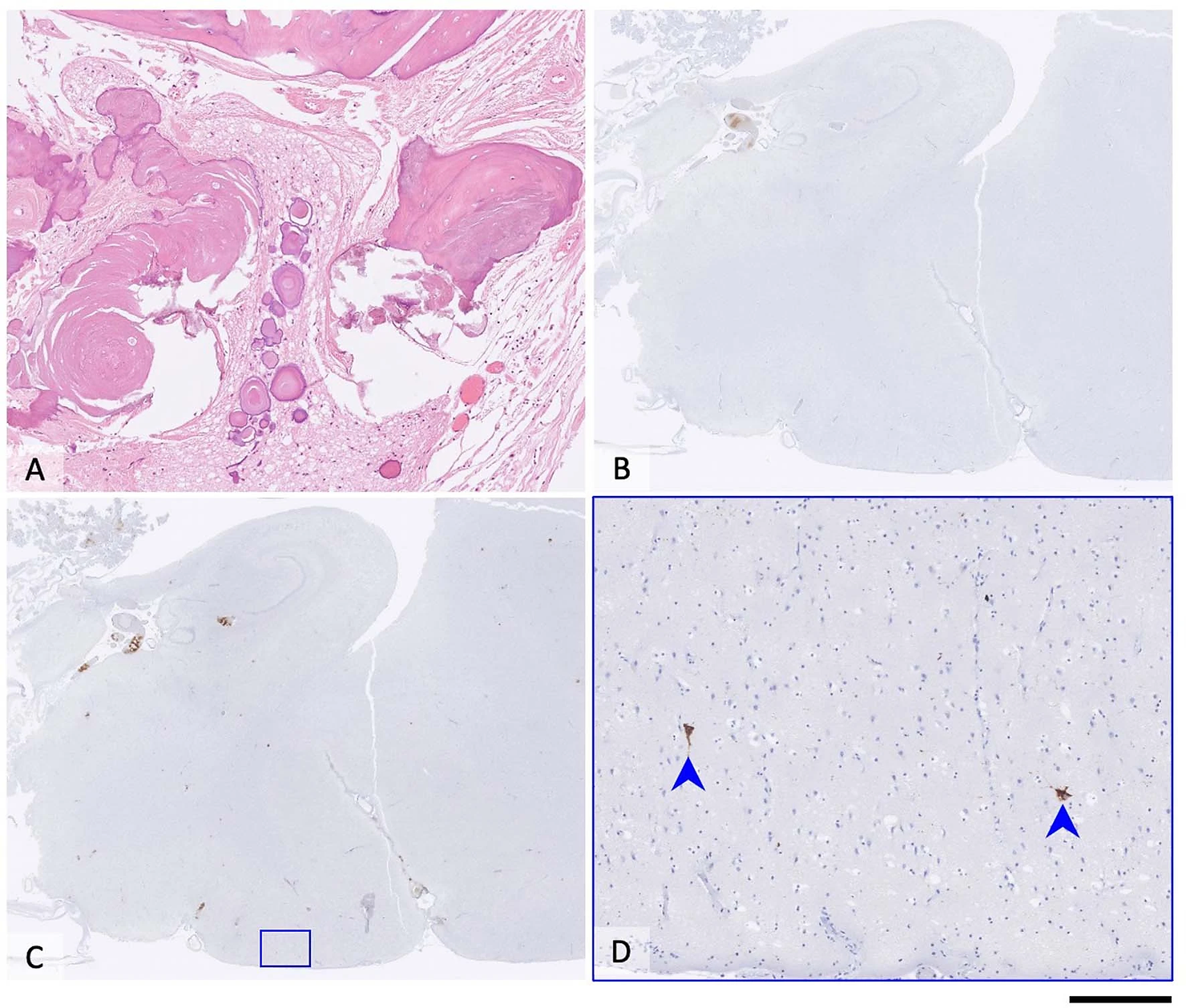

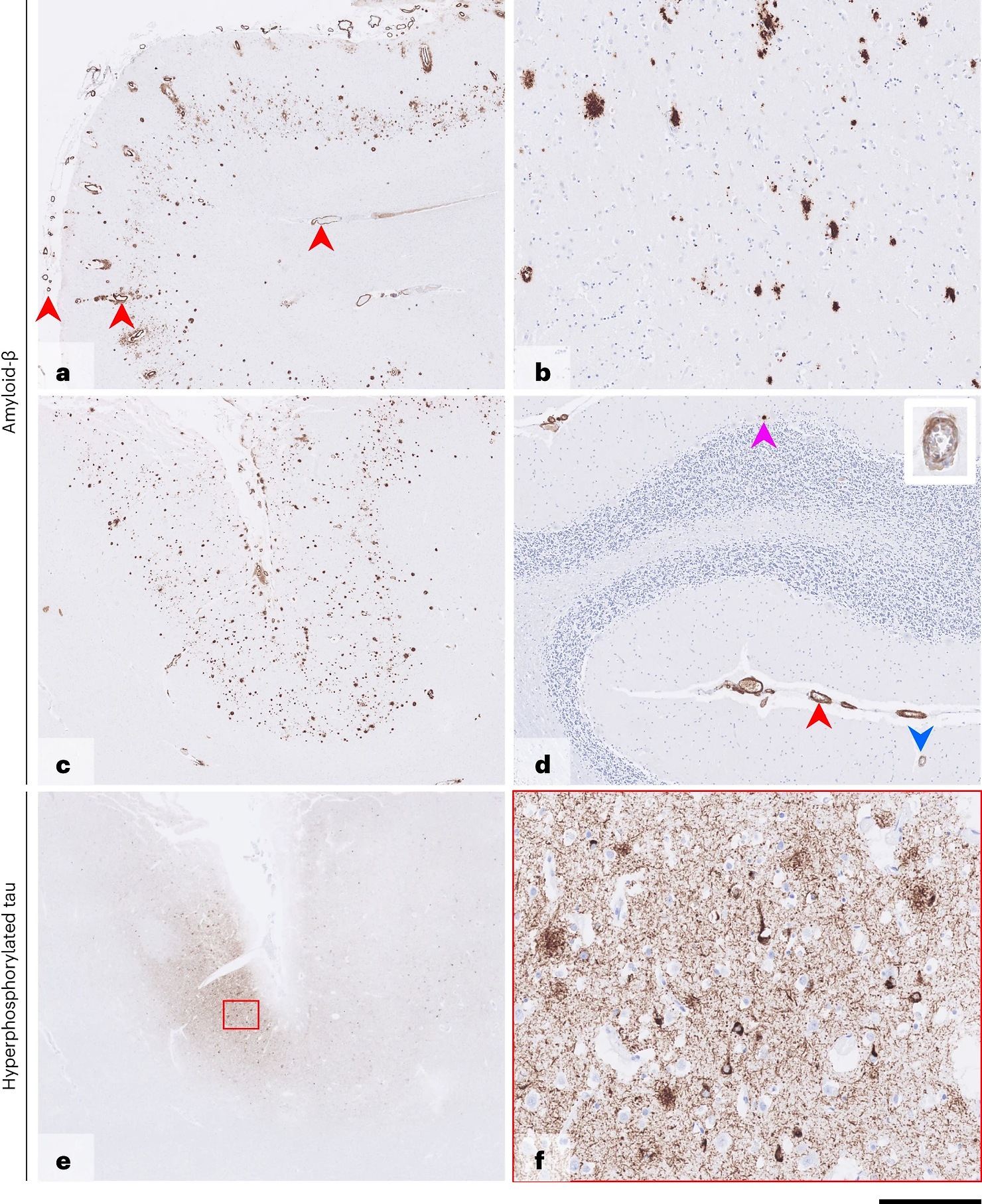

Earlier research by the same scientists had already established a troubling link between c-hGH and amyloid-beta protein deposits. Some individuals who developed iatrogenic CJD after receiving c-hGH also showed signs of premature amyloid buildup in their brains.

In 2018, the team provided further evidence of contamination. They analyzed archived c-hGH samples and confirmed the presence of amyloid-beta proteins. When injected into laboratory mice, these proteins triggered amyloid pathology, reinforcing concerns about potential transmission risks.

This latest study deepens the concern, showing that individuals who received contaminated c-hGH decades ago are now exhibiting early signs of Alzheimer’s. Their findings challenge long-held assumptions that Alzheimer’s cannot be transmitted between people.

Related Stories

Building upon these findings, the researchers hypothesized that individuals exposed to contaminated c-hGH who did not succumb to CJD might eventually develop Alzheimer’s disease.

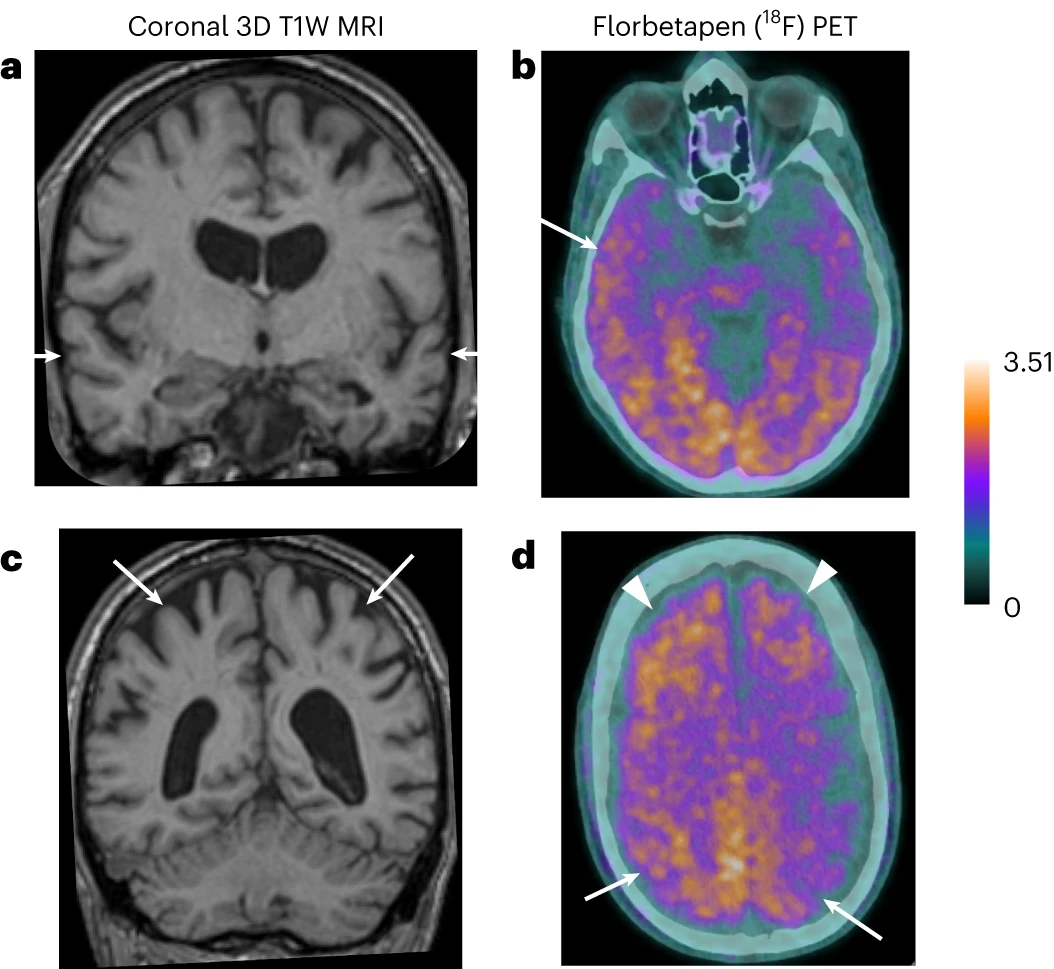

This latest paper details the cases of eight individuals who had received c-hGH treatment during their childhood, often spanning several years. Five of these individuals exhibited symptoms of dementia, either with a confirmed Alzheimer’s diagnosis or meeting the diagnostic criteria for the disease.

The onset of neurological symptoms occurred surprisingly early, with the patients ranging in age from 38 to 55 when they first experienced symptoms.

Biomarker analyses further supported the diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease in two patients and hinted at Alzheimer’s in another individual. An autopsy analysis confirmed Alzheimer’s pathology in yet another patient. The unusually young age at which these patients developed symptoms strongly suggests that this was not the typical late-onset sporadic Alzheimer’s.

Genetic testing ruled out inherited Alzheimer’s disease in the five patients who provided samples. Since c-hGH treatment is no longer in use, there is no risk of new transmissions through this method.

Moreover, there have been no reported cases of Alzheimer’s disease acquired through any other medical or surgical procedures, nor any indication that amyloid-beta can be transmitted during routine medical or social care.

However, the researchers emphasize the importance of reviewing safety measures to prevent the accidental transmission of amyloid-beta through other medical or surgical procedures that have previously been linked to CJD transmission.

Professor John Collinge, the lead author of the research and Director of the UCL Institute of Prion Diseases, clarified, “There is no suggestion whatsoever that Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted between individuals during activities of daily life or routine medical care.” He added that these cases were linked to a specific and discontinued medical treatment involving contaminated materials.

Professor Jonathan Schott, a co-author and Chief Medical Officer at Alzheimer’s Research UK, echoed the sentiment that while these cases are highly unusual, they offer valuable insights into disease mechanisms that could be instrumental in understanding and treating Alzheimer’s disease in the future.

Dr. Gargi Banerjee, the first author of the study, highlighted, “We have found that it is possible for amyloid-beta pathology to be transmitted and contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.”

However, she emphasized that this transmission occurred only after repeated treatments with contaminated material, reiterating that Alzheimer’s disease cannot be acquired through close contact or routine care provision.

The discovery of Alzheimer’s transmission through c-hGH treatment underscores the intricate nature of this debilitating disease, paving the way for further research and a deeper understanding of its causes and potential treatment strategies.

Scientists do not yet fully understand what causes Alzheimer’s disease. There likely is not a single cause but rather several factors that can affect each person differently.

In 2010, the costs of treating Alzheimer’s disease were projected to fall between $159 and $215 billion. By 2040, these costs are projected to jump to between $379 and more than $500 billion annually.

Death rates for Alzheimer’s disease are increasing, unlike heart disease and cancer death rates that are on the decline.

Dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, has been shown to be under-reported in death certificates and therefore the proportion of older people who die from Alzheimer’s may be considerably higher.

Note: Materials provided above by the The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get the Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New study finds that Alzheimer’s can be passed from one person to another appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.