Every step you take depends on a structure most people rarely think about. The pelvis sits at the center of the body and quietly supports nearly every movement. It holds the spine upright, steadies balance, and allows walking to feel natural. Yet this familiar motion was once anything but ordinary. Over millions of years, the pelvis changed more than any other lower-body bone, helping shape the story of how humans learned to walk on two legs.

Scientists have long known that the human pelvis looks nothing like that of other primates. While apes rely on climbing and knuckle-walking, humans move upright with ease. What remained unclear was how evolution carried out such a dramatic redesign. A new study led by researchers at Harvard University now provides strong answers, showing that two major genetic and developmental changes reshaped the pelvis and made upright walking possible.

“What we’ve done here is demonstrate that in human evolution there was a complete mechanistic shift,” said Terence Capellini, professor and chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology. “There’s no parallel to that in other primates.” He explained that major evolutionary changes often involve deep alterations in how bodies grow, and the human pelvis followed that same pattern.

In chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas, the upper hip bones are tall, narrow, and flat from front to back. From the side, they resemble thin blades. This structure supports powerful muscles needed for climbing and swinging through trees. It suits life spent largely above the ground.

The human pelvis tells a very different story. The hip bones rotate outward and curve into a wide basin shape. This structure allows muscles to stabilize the body while weight shifts from one leg to the other. That balance is essential for walking and running upright. Even the word pelvis comes from Latin, meaning basin, a reflection of its shape.

While these differences have been obvious to anatomists for decades, the process behind them remained uncertain. How did evolution transform a climbing frame into a structure built for walking long distances? The answer, researchers found, begins early in development.

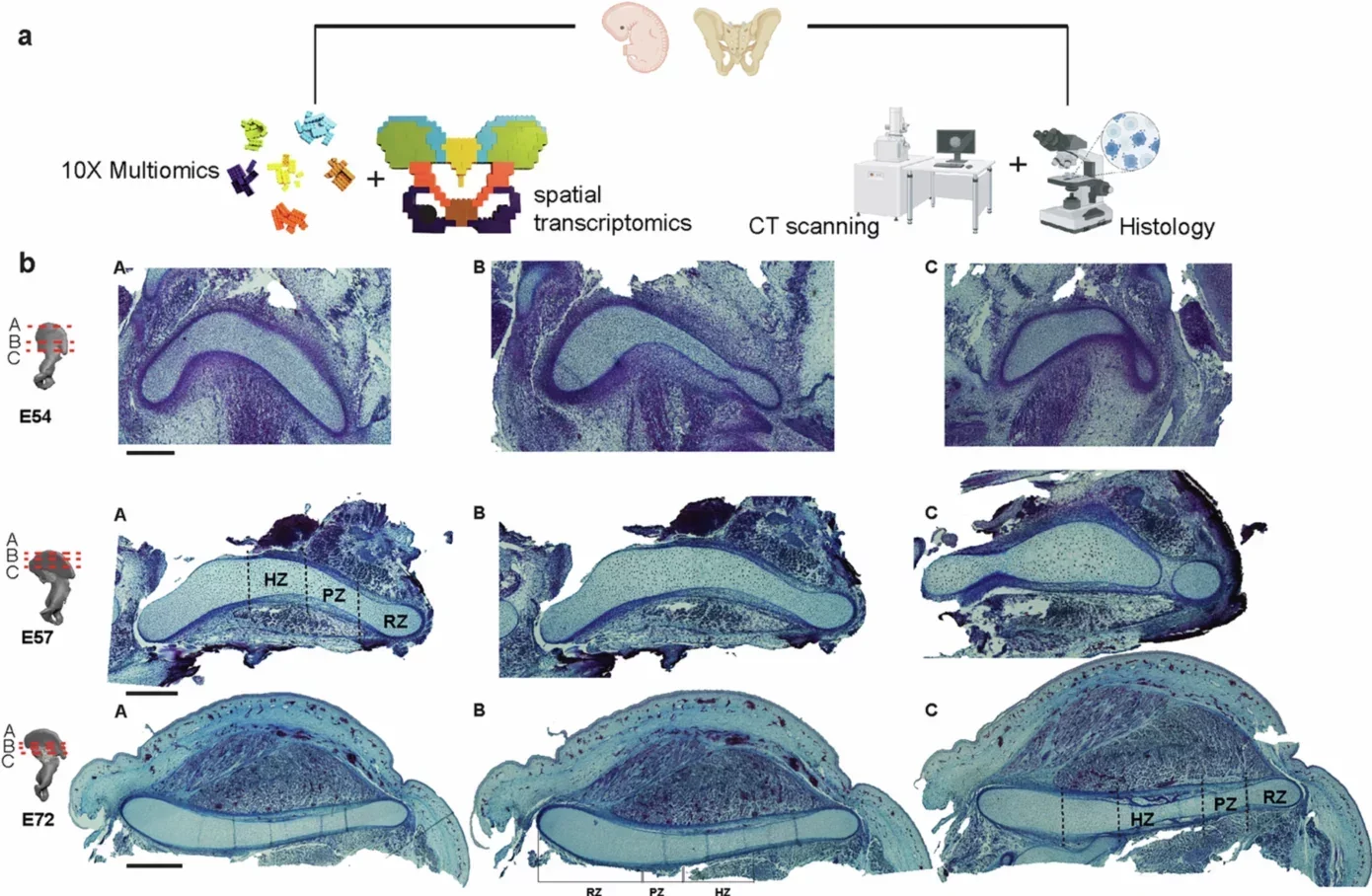

To uncover the origins of the pelvis, scientists examined how it forms before birth. Study lead author Gayani Senevirathne analyzed 128 embryonic tissue samples from humans and nearly two dozen other primate species. Some specimens were preserved more than a century ago in museum collections across the United States and Europe. Others came from the Birth Defects Research Laboratory at the University of Washington.

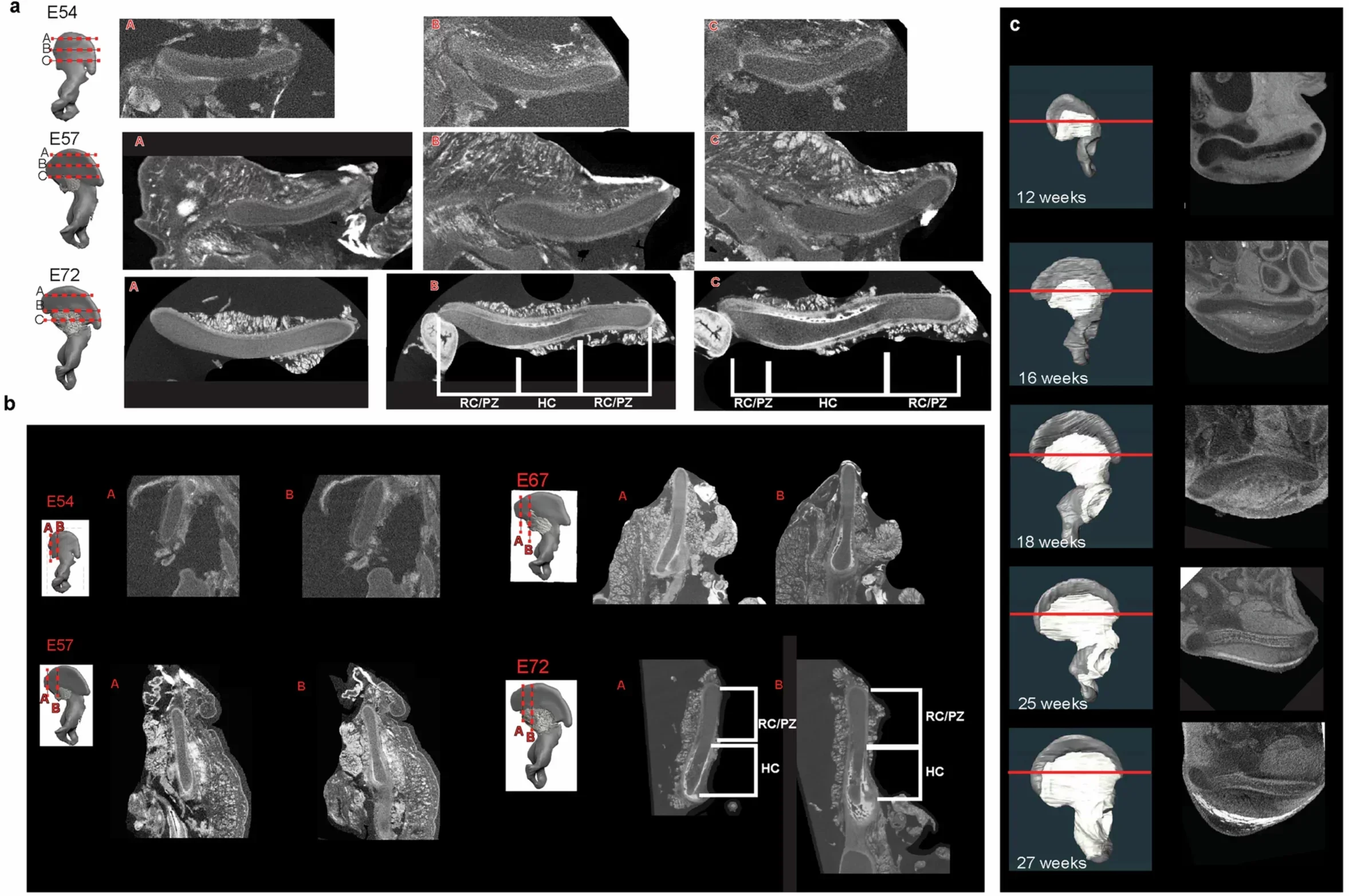

Using CT scans and microscopic tissue analysis, the team traced pelvic growth during early development. This allowed them to observe how cartilage and bone formed step by step. “What we tried to do was integrate different approaches,” Senevirathne said. “That helped us see the full story.”

Capellini praised the scope of the work. “The work that Gayani did was a tour de force,” he said. “This was like five projects in one.” What the team discovered surprised even experienced researchers.

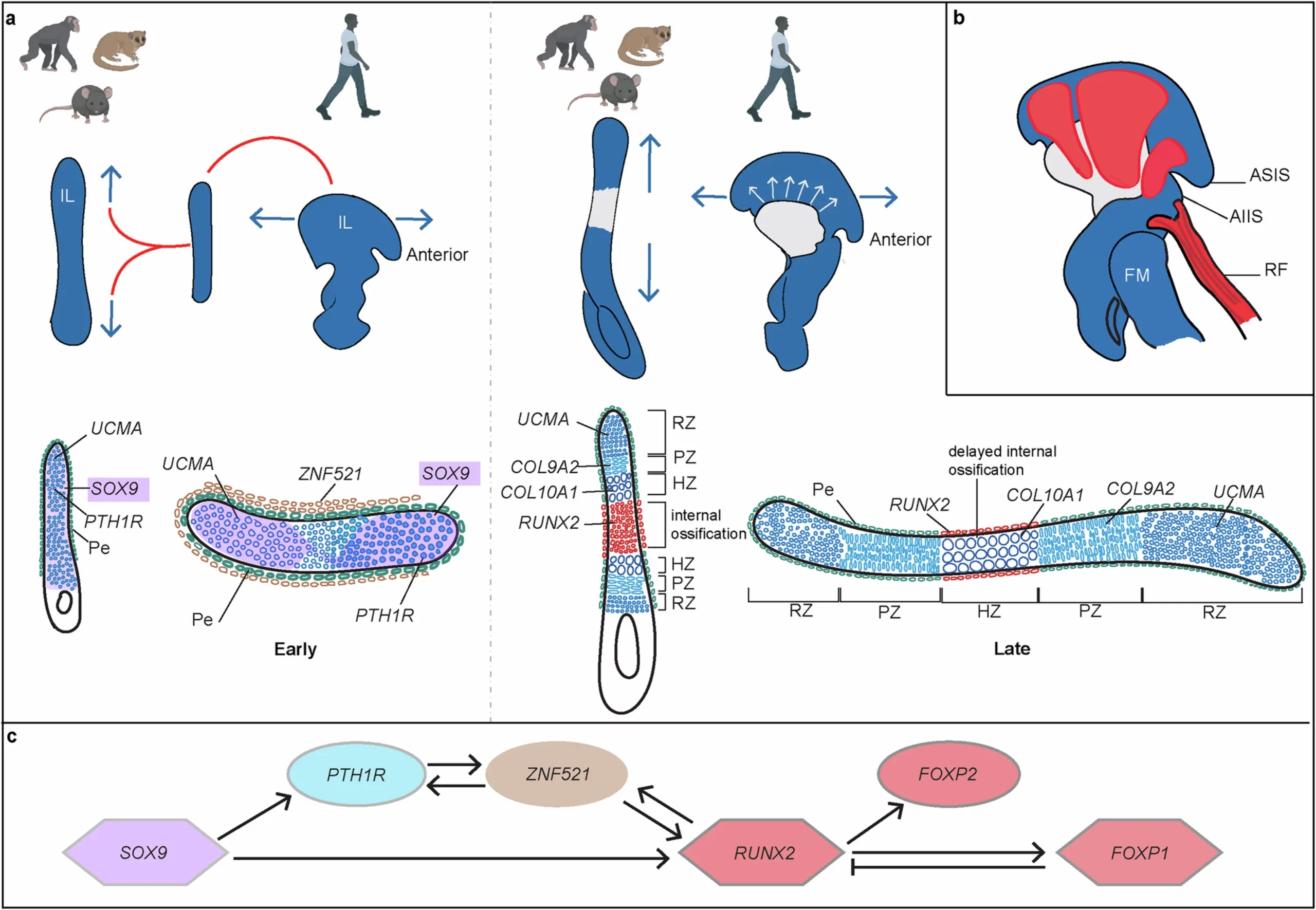

The first major evolutionary change involved the growth plate, a region of cartilage that directs how bones expand. In most primates, this plate runs from head to tail, creating a tall hip bone. Early human development begins the same way.

Then something dramatic happens. By about day 53, the growth plate rotates sharply. It turns ninety degrees and begins expanding sideways instead of upward. This shift shortens and widens the hip bone at the same time.

“Looking at the pelvis, that wasn’t on my radar,” Capellini told The Brighter Side of News. “I expected gradual change. The tissue showed a full flip.” This sudden reorientation laid the foundation for the wide, stable pelvis seen in humans today.

The second transformation involved timing. Bones start as cartilage before hardening through a process called ossification. In most bones, hardening begins in the center and spreads outward.

The human pelvis follows a different pattern. Bone formation begins near the back of the pelvis and spreads outward, while the inner cartilage stays soft much longer. This delay lasts roughly 16 weeks and allows the pelvis to maintain its basin shape as it grows.

“Embryonically, at 10 weeks you have a pelvis,” Capellini said. “It looks basin shaped.” That extra time before hardening helped lock in a structure suited for upright movement.

To understand what caused these changes, researchers examined gene activity in developing tissue. They identified more than 300 active genes. Three played especially strong roles. SOX9 and PTH1R guided the rotation of the growth plate, while RUNX2 influenced the timing of bone hardening.

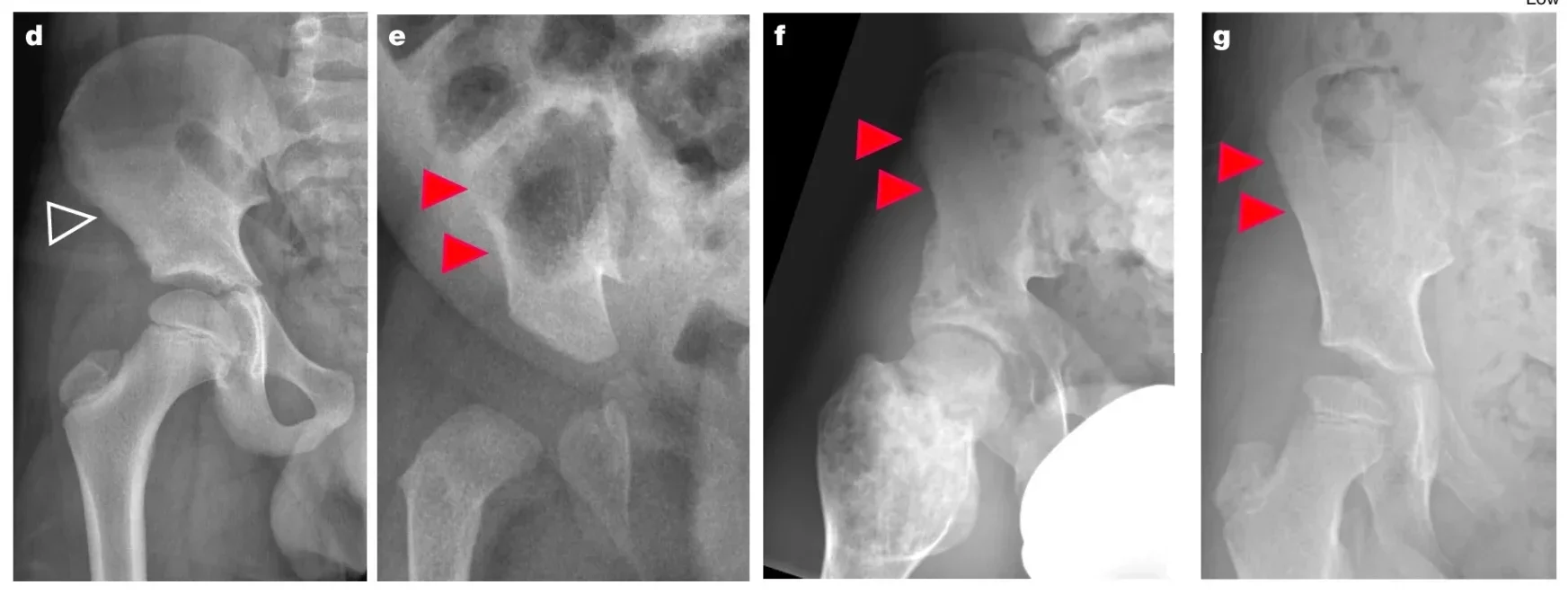

The importance of these genes appears in human disease. Mutations in SOX9 can cause Campomelic Dysplasia, which leads to narrow hip bones that lack outward flare. Changes in PTH1R also result in abnormal pelvis shape and skeletal disorders. These medical links reinforced the study’s conclusions.

The researchers believe the first pelvic changes began between 5 and 8 million years ago, around the time early humans separated from African apes. The pelvis then remained under constant pressure as evolution continued.

As brains grew larger, childbirth became more difficult. A narrow pelvis supports efficient walking, while a wider one helps deliver infants. This tension, known as the obstetrical dilemma, likely shaped pelvic evolution for millions of years. The delayed hardening of bone may have helped balance both demands.

Fossils support this timeline. The 4.4 million year old Ardipithecus pelvis shows both climbing and walking traits. The 3.2 million year old Lucy skeleton shows stronger features for upright movement. Each fossil fits the developmental story revealed by the new research.

Capellini believes these findings should change how scientists interpret the fossil record. “All fossil hominids from that point on were growing the pelvis differently from any other primate that came before,” he said. Later increases in brain size, he argues, must be understood within this new developmental framework rather than compared directly with apes.

The pelvis changed first. Many other human traits followed.

This research reaches beyond questions of ancient history. Understanding pelvic development may help explain birth complications, hip disorders, and skeletal diseases. It also provides a clearer model for how small changes early in development can shape the entire body.

For science, the study strengthens links between genetics, anatomy, and evolution. For humanity, it deepens understanding of how a single bone helped humans travel the world on two feet.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New study reveals how the human pelvis evolved for upright walking appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.