In Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, a protein called tau can pile up inside brain cells and form toxic clumps. Those clumps help drive memory loss and other symptoms. Yet some neurons seem to hold on longer than others. New work from UCLA Health and UC San Francisco helps explain why; it also points to new places scientists might target with future drugs.

Researchers from the two universities, led by neurologist Dr. Avi Samelson, used lab-grown human neurons to map the cell systems that raise or lower tau. Samelson is now an assistant professor of Neurology at UCLA Health; he did much of the work while at UC San Francisco. The team published the study in Cell.

Tau normally helps stabilize microtubules, the internal tracks that help neurons keep shape and move materials. In tau-related diseases, tau changes form and begins to stick to itself. Some cases stem from inherited mutations, including changes in the MAPT gene that can cause familial frontotemporal dementia. Most cases, including most Alzheimer’s disease, are not inherited. That gap has left scientists hunting for the cell conditions that push tau into harmful shapes.

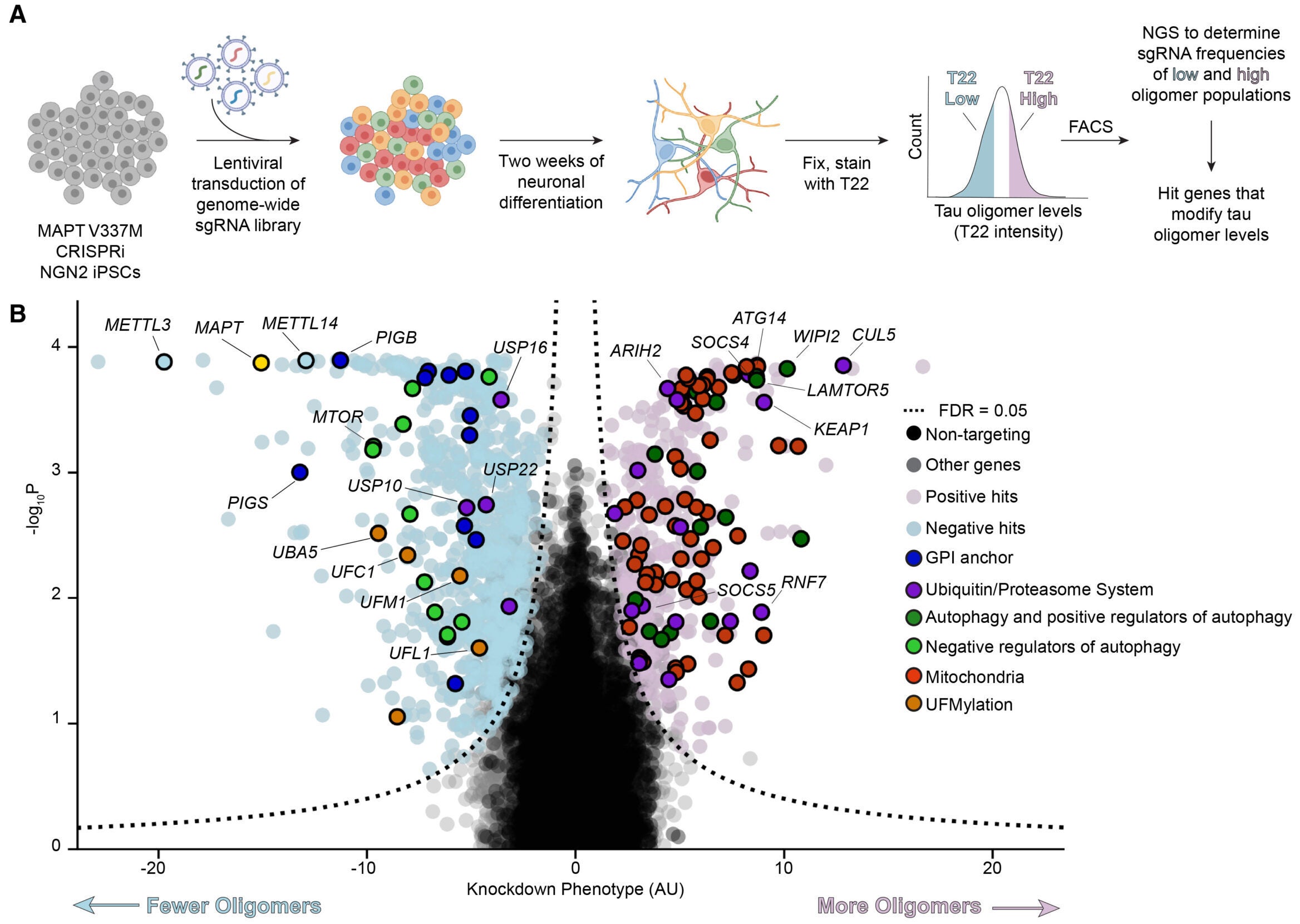

To tackle that problem, the researchers turned to a powerful approach: a genome-wide screen using CRISPR interference, also called CRISPRi. Instead of cutting DNA, CRISPRi can dial down gene activity. This let the team test the effects of knocking down almost every human gene, one by one, in neurons grown from induced pluripotent stem cells.

Their neurons carried a tau mutation linked to frontotemporal dementia, called MAPT V337M. The system mattered for Alzheimer’s research too, because tau with that mutation can form fibrils similar to those seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

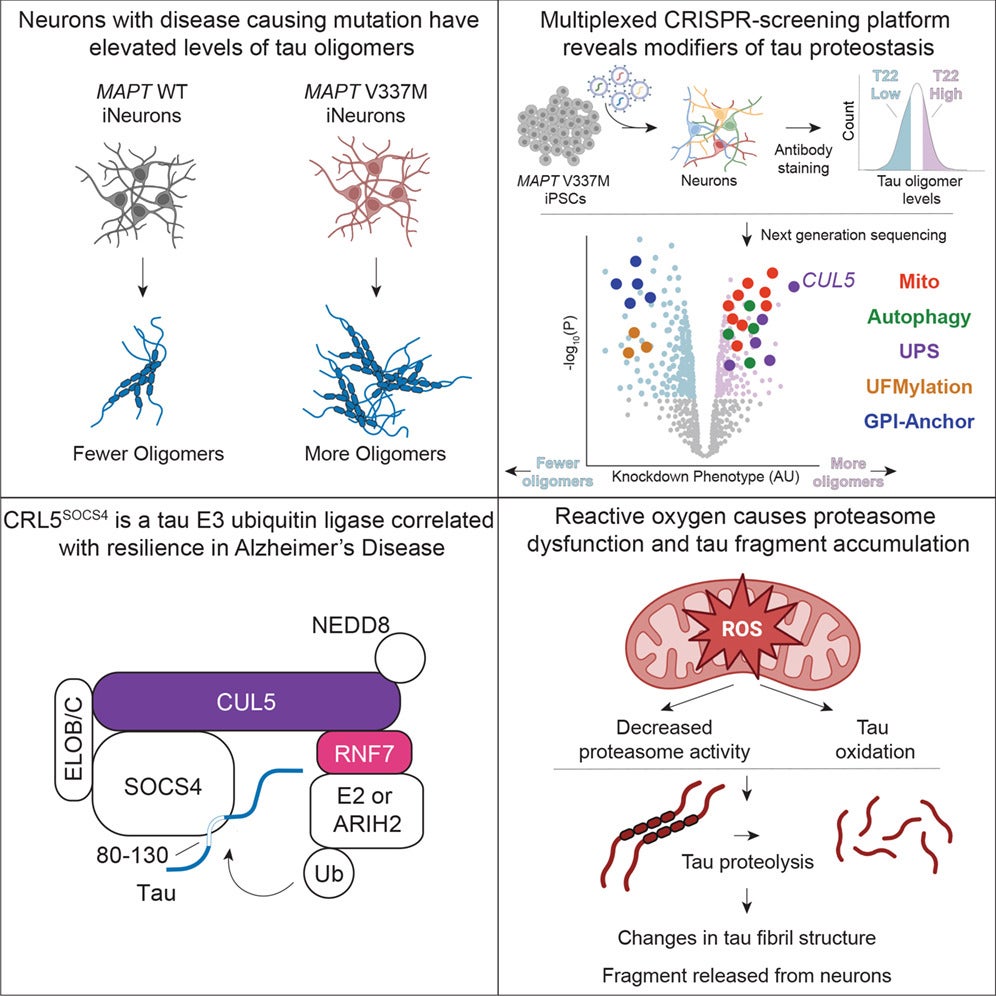

The team first focused on tau oligomers, early clumps that appear before larger fibrils and may be especially damaging. Using an antibody called T22, they found higher oligomer signals in neurons with the V337M mutation. When they knocked down MAPT, the T22 signal dropped, showing the readout truly reflected tau.

With a reliable signal in hand, they screened a library of more than 100,000 guide RNAs that targeted essentially all protein-coding genes. The results were broad. At a strict statistical cutoff, the team identified 1,143 genes that changed tau oligomer levels.

“We wanted to understand why some neurons are vulnerable to tau accumulation while others are more resilient,” Samelson said. “By systematically screening nearly every gene in the human genome, we found both expected pathways and completely unexpected ones that control tau levels in neurons.”

Some results matched what scientists already suspected. When the team weakened parts of autophagy, the cell’s bulk recycling system, tau oligomers rose. Genes tied to the ubiquitin-proteasome system, another major cleanup pathway, also mattered.

But one signal stood out across repeated tests: a protein complex that labels tau for destruction. At the center was CUL5, part of a larger ubiquitin ligase machine. The researchers traced it to a specific version of the complex, called CRL5SOCS4.

In simple terms, this system works like a tagging step before trash pickup. It attaches molecular labels to tau, sending it toward the proteasome, a cellular machine that breaks proteins down. When the team reduced key CRL5 parts, tau levels climbed, especially in the neuron’s cell body.

To show that the effect happened after tau was already made, the researchers built a dual-fluorescent reporter. The tool compared a tau-linked signal to a second marker made from the same message. If the tau-linked signal rose, it suggested tau was lasting longer, not being produced more.

When the team knocked down CUL5, the tau-linked signal increased. A proteasome inhibitor, MG132, erased that effect, tying the pathway to proteasome-based breakdown.

They also narrowed down the part of tau that seemed required for recognition. A segment spanning residues 80–130 behaved like a key handle. When that region was present, CUL5 knockdown raised tau. When it was not, the effect disappeared.

Another clue came from adaptor proteins that help the CRL5 complex recognize its targets. Two candidates, SOCS4 and SOCS5, appeared in the genetic hits. SOCS4 was stronger. When the researchers increased SOCS4 activity, both tau oligomers and total tau dropped, fitting the idea that SOCS4 helps the complex find tau.

The genetic screens also kept pointing to mitochondria, the cell’s energy centers. When the team disrupted genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, tau oligomers rose. They then tested a drug approach by treating neurons with rotenone, which blocks a key step in mitochondrial energy production.

Rotenone raised tau, and it also triggered something unexpected: a tau fragment about 25 kilodaltons in size. The fragment resembled a biomarker found in blood and spinal fluid of Alzheimer’s patients, known as NTA-tau.

“This tau fragment appears to be generated when cells experience oxidative stress, which is common in aging and neurodegeneration,” Samelson said. “We found that this stress reduces the efficiency of the proteasome, the cell’s protein recycling machine, causing it to improperly process tau.”

The fragment showed up not only inside neurons but also in the fluid around them. That mattered because Alzheimer’s diagnostics increasingly rely on measurable markers in blood and cerebrospinal fluid. The team’s data suggested the fragment was not just general tau leakage; it looked like a specific stress-linked product.

To pin down the trigger, the researchers tested other mitochondrial drugs and direct oxidative stress. Some treatments that raise reactive oxygen species produced the fragment. Hydrogen peroxide caused near-complete conversion of tau into the 25-kilodalton piece.

They then asked which protein-cutting system made the fragment. Surprisingly, blocking the proteasome reduced fragment formation. Native gels showed that rotenone lowered activity of several proteasome forms without lowering proteasome protein levels. That pattern fit a “processivity” problem, where the proteasome still works but handles tau poorly under stress.

The team also highlighted a proteasome helper called PA28. Increasing PA28 parts reduced fragment formation. Lowering PA28 increased it. Tau oxidation itself seemed to contribute too. A tau version without methionines formed far less fragment.

Finally, test-tube experiments suggested the fragment could alter how tau aggregates. Adding increasing amounts of a tau 1–172 fragment changed both the speed and the final signal of fibril formation; electron microscopy suggested straighter fibrils as the fragment increased.

A major question is whether the tau-tagging system matters in real brains. The researchers analyzed existing human brain datasets and found that higher expression of CRL5-related genes tracked with greater neuronal survival in Alzheimer’s disease. Components tied to the complex, including CUL5, RNF7, ARIH2, and SOCS4, showed associations with resilience across cell types and in specific neuron groups.

The study also flagged other pathways not often linked to tau control, including UFMylation and GPI anchor biosynthesis. These hits do not yet have a clear place in tau disease biology, but they widen the map of possible mechanisms.

“What makes this study particularly valuable is that we used human neurons carrying an actual disease-causing mutation,” Samelson said. “These cells naturally have differences in tau processing, giving us confidence that the mechanisms we identified are relevant to human disease.”

Funding came from the Rainwater Charitable Foundation/Tau Consortium, the National Institutes of Health and other sources.

If you want treatments that slow Alzheimer’s disease, you need ways to keep tau from building into toxic forms. This work suggests two promising directions.

First, boosting the CRL5SOCS4 tau-tagging pathway could help neurons clear tau before it clumps. Drug developers could look for compounds that strengthen this tagging system or improve how it recognizes tau. The human brain data adds weight by linking higher expression of key components to neuron survival.

Second, the study connects oxidative stress to the creation of an NTA-tau-like fragment, while also pointing to proteasome performance as a choke point. That link may help researchers interpret blood and spinal fluid tau tests, and it may guide strategies aimed at keeping proteasomes working during cellular stress.

Together, these findings give scientists a clearer set of targets and measurable signals. Over time, that could translate into better diagnostics, better drug screening, and therapies designed around the biology of resilient neurons.

Research findings are available online in the journal Cell.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New study reveals why some brain cells resist Alzheimer’s and dementia appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.