In most buildings, windows remain the most vulnerable part of the structure when it comes to energy loss. Worldwide, buildings account for roughly 40% of total energy use, much of it spent keeping indoor spaces comfortable. A significant share of that energy escapes through walls, roofs, and especially windows. Although windows often cover only about 8% of a building’s exterior, they can account for nearly half of the heat moving in and out. In modern homes with large glass surfaces, that fraction can climb much higher.

Engineers have long searched for materials that insulate as well as walls but remain clear like glass. Options such as vacuum-insulated glass or transparent aerogels exist, yet each comes with drawbacks. These materials can be costly, difficult to manufacture at scale, or prone to cloudiness as thickness increases. Once aerogels grow thicker than a few millimeters, they scatter light and lose clarity, limiting their usefulness for windows.

The challenge lies in structure. Many insulating materials rely on trapping air, but if the internal pores vary too much in size, they scatter light and allow heat to pass. To work well, an ideal window insulator needs pores smaller than visible light and smaller than the distance air molecules travel before colliding. At room conditions, that distance is about 60 nanometers.

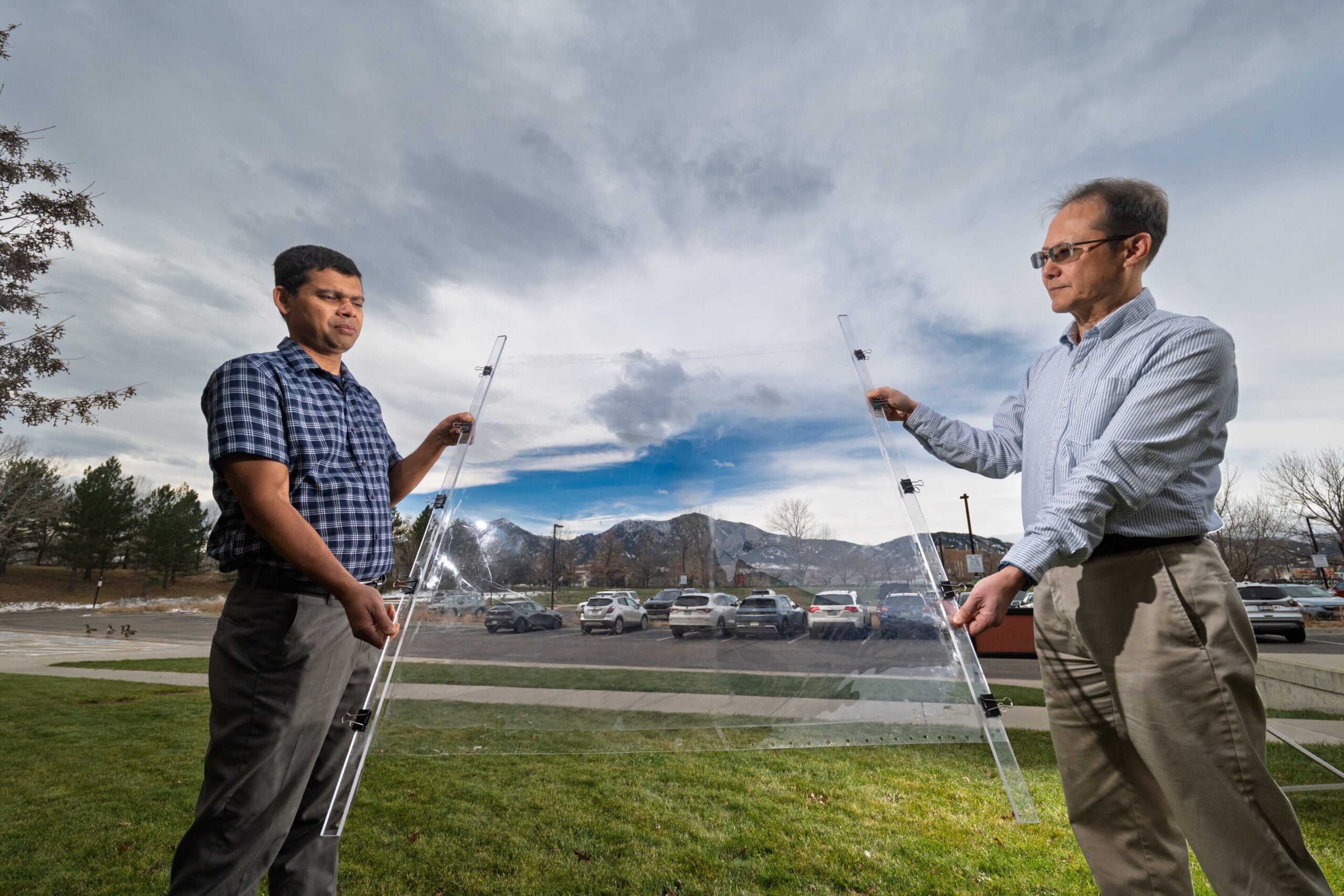

Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder believe they have found a solution. Physicists there have developed a new transparent insulating material known as a Mesoporous Optically Clear Heat Insulator, or MOCHI. The material behaves like a highly controlled version of frozen air, trapping heat while remaining almost invisible.

MOCHI consists of a network of hollow silicone nanotubes arranged in a highly uniform pattern. Air makes up more than 90% of its volume, yet the solid framework keeps those air pockets stable and evenly spaced. By limiting solid material to just 5% to 15%, the team achieved both low heat flow and high transparency.

Tests showed that thin MOCHI sheets transmit more than 99% of visible light, with almost no haze. Ordinary window glass typically transmits less than 92%. At the same time, MOCHI conducts heat at less than half the rate of still air. According to Ivan Smalyukh, senior author of the study and a physics professor at CU Boulder, that balance has been elusive.

“To block heat exchange, you can put a lot of insulation in your walls, but windows need to be transparent,” Smalyukh said. “Finding insulators that are transparent is really challenging.”

The team reported its findings in the journal Science.

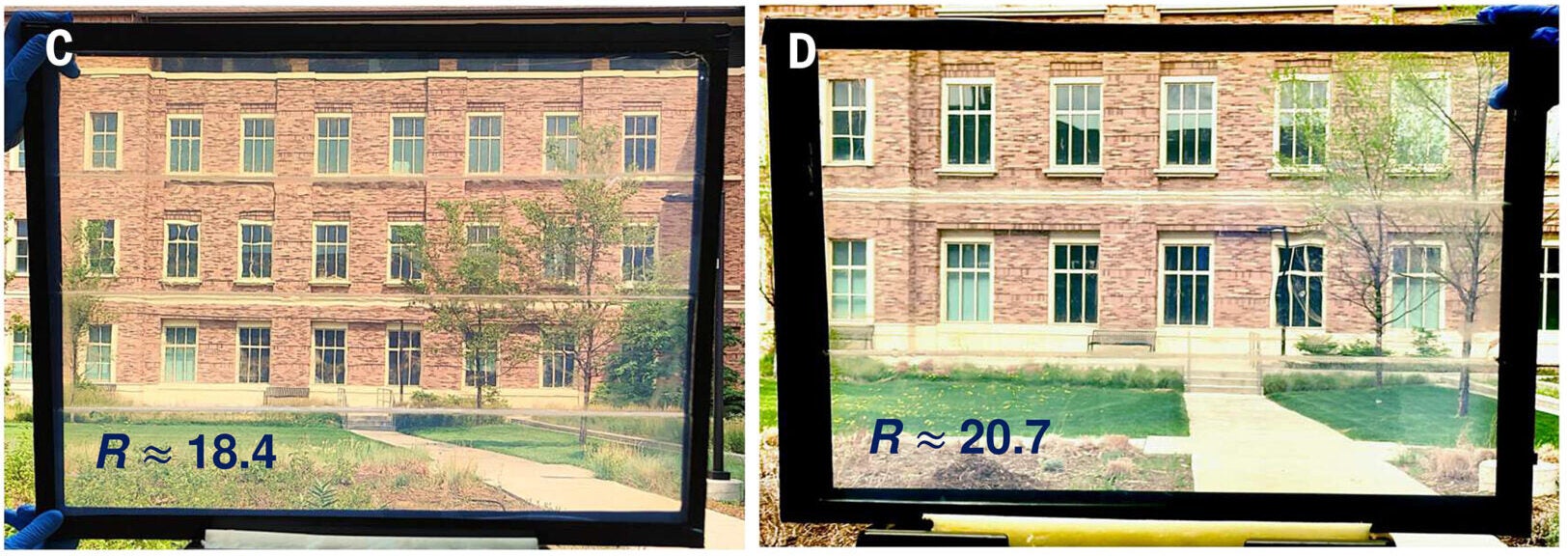

One of the most promising aspects of MOCHI is scalability. The researchers produced square-meter-sized films and slabs several centimeters thick without sacrificing clarity or insulation. These slabs can be placed inside insulated glass units, or IGUs, similar in thickness to standard double-pane windows.

When used this way, MOCHI-filled windows reached insulation levels comparable to or better than well-insulated walls. Even thin layers adhered to the inside of single-pane windows significantly improved performance, bringing them close to double-pane standards. Infrared imaging revealed much less heat leakage compared with conventional windows.

MOCHI also helps with everyday comfort. By blocking thermal radiation, it reduces condensation and dampens sound. In tests, MOCHI windows cut noise by up to 35 decibels at certain frequencies, outperforming standard double-pane glass.

The manufacturing process relies on controlled self-assembly. Researchers mix silicone precursors with surfactant molecules that naturally form tiny threads in solution. Silicone coats these threads, and later steps replace the surfactant with air. The result is a dense maze of microscopic air-filled tubes. Smalyukh compares the structure to a “plumber’s nightmare,” but one that works beautifully for insulation.

Under a microscope, MOCHI looks very different from traditional aerogels. Instead of clumps of particles with random gaps, it forms an orderly network of uniform pores. This structure allows light to pass through with minimal scattering. Its refractive index is close to that of air, meaning little light reflects off its surface.

Because the pores are smaller than the path air molecules travel, heat transfer slows dramatically. Gas molecules collide with pore walls rather than each other, limiting energy exchange. The silicone framework itself also resists heat flow.

In thicker slabs, MOCHI absorbs and reemits thermal infrared radiation, further reducing heat loss. Combined, these effects make the material an effective barrier against both cold and heat, while staying nearly invisible.

The material also shows mild optical effects due to partial alignment of its nanotubes. While not critical for windows, these properties could prove useful in future optical devices. For everyday use, MOCHI maintains excellent color accuracy, meaning outdoor views appear natural.

Beyond insulation, MOCHI may help buildings generate energy. The material lets visible and near-infrared sunlight pass while trapping longer-wavelength heat radiation. When paired with a dark absorber, MOCHI allows sunlight in but holds much of the heat inside.

Experiments showed that MOCHI-covered absorbers reached temperatures near 300 degrees Celsius under regular sunlight. Even on cloudy days, the system continued to collect usable heat. Simulations suggest that covering part of a home’s exterior with such panels could meet heating needs, and larger installations could generate surplus energy.

“Durability tests indicate that MOCHI-based products can last at least 20 years, similar to conventional IGUs. Samples adhered to interior window surfaces survived about five years in real conditions, including dust, acid rain, and chemical exposure, without losing their key properties. The material is mechanically robust, can be rolled in thin films, laser-cut into complex shapes, and remains superhydrophobic, fire retardant, and water-repellent,” Smalyukh told The Brighter Side of News.

MOCHI could change how buildings manage energy. By turning windows into high-performance insulators, architects could use more glass without sacrificing efficiency. Homes and offices could reduce heating and cooling demands, lowering energy bills and emissions. The material’s durability suggests it could last decades in real-world conditions.

Beyond buildings, MOCHI may find use in greenhouses, protective clothing, and solar thermal systems. Its combination of clarity and insulation opens possibilities where visibility and temperature control both matter. With further development, the same structure could support air cleaning or adaptive solar control.

“For now, MOCHI will remain a laboratory product. The ingredients are still relatively inexpensive, and we still have work to do in improving our manufacturing process,” Smalyukh shared with The Brighter Side of News.

If that happens, windows may one day stop leaking energy and start helping generate it.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New transparent window material could cut building energy loss by 50% appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.