By bringing the long-standing and opposing views of quantum mechanics together to form a single cohesive theory, a research team at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Heidelberg, Germany, has made a significant advance in our understanding of how quantum matter interacts with itself at very low temperatures. The researchers have developed a framework that explains the behavior of a single exotic particle in a sea of fermions (a group of particles that are governed by the Pauli exclusion principle), as well as for a number of different types of experiments.

The study was led by Professor Richard Schmidt and his Quantum Matter Theory group, including doctoral student Eugen Dizer. It was published in Physical Review Letters and funded by Heidelberg University’s STRUCTURES Cluster of Excellence and the ISOQUANT Collaborative Research Centre 1225.

The fundamental question that the researchers aimed to answer was: how does an impurity particle behave in a cold fermionic sea? Over many decades, physicists have relied on two different answers to this question. One answer has been based on the assumption that the impurity particle could move freely among the cold fermionic sea of particles (i.e., mobile impurities), while the other answer assumes that the impurity particle remains fixed in place (i.e., fixed impurities).

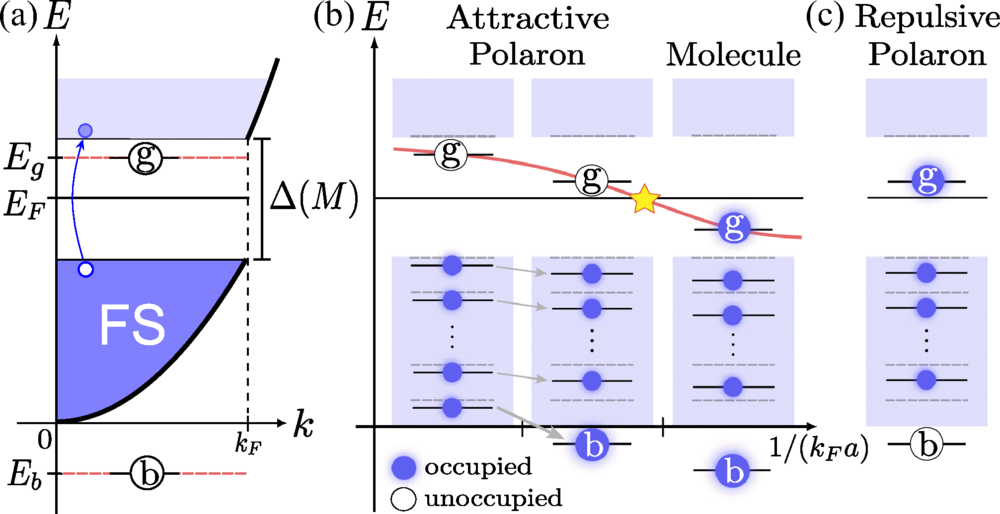

In the case of a mobile impurity, the idealised picture of the impurity and its surrounding particles is one in which the two behave as if they are joined together as a single entity (a quasiparticle) that experiences interactions with other particles in the cold fermionic sea. When an impurity is added to a system of particles, it becomes a type of quasiparticle called a Fermi polaron.

According to Eugen Dizer, “the quasiparticle model has become a major tool for studying strongly correlated systems.” By understanding how quasiparticles behave in cold atomic gases and condensed matter, as well as in nuclear matter, the quasiparticle model has been valuable to scientists who study materials that interact strongly with one another. Although quasiparticles behave as if they are single particles, they only form through the cooperation of many particles.

In the example of motion of an impurity, “the impurity has kept its identity… and the quantum state of the impurity plus the other particles in the system is the same as that of the other particles.” The overlap between the two states is known as the “quasiparticle weight,” and therefore experiments can determine the overlap between the two states.

When an impurity has an infinite mass, the impurity is effectively frozen in the sense that it does not move. In 1970, Philip Anderson presented a theory (known as Anderson’s orthogonality catastrophe) describing how an immobile impurity reshapes the quantum states of all the surrounding fermions in such a way that the original states and the altered states are orthogonal to one another.

As the number of constituent particles grows, the overlap between the original and altered states approaches zero. In other words, without an overlap, the very concept of an official quasiparticle loses coherency. Until recently, the contrasting outcomes observed in quasiparticles and in immobile impurities were mystery; no theory could successfully connect the two models.

Using analytical methods and a new way to define the problem, the Heidelberg group can now link the extreme limits of these two types of particles.

According to Dr. Dizer, “We have developed a theoretical framework that describes how quasiparticles form from heavy impurities in a continuum model. This model combines two previously competing ideas into one coherent description.”

The researchers formulated their approach to address the impurity problem by reformulating the existing equations of motion of the impurity and its surrounding fermion. They incorporated the impurity’s movement within the equations for the fermions with a canonical transformation.

So, rather than treating the impurity’s motion independently from the fermions, Dizer and colleagues treated both together, eliminating the need for an explicit position dependence of the impurity with respect to the fermionic system; thus, by eliminating the direct correlation between the impurity and the surrounding fermionic fields, a new form of effective interaction among the fermionic fields was created.

This new form of interaction results from a simple observation: all heavy impurities released from the surrounding fermionic fields can still be moved. Whenever the surrounding particles are moved, the impurity also moves, leading to a slight recoil. This recoil produces small energy changes in the particle.

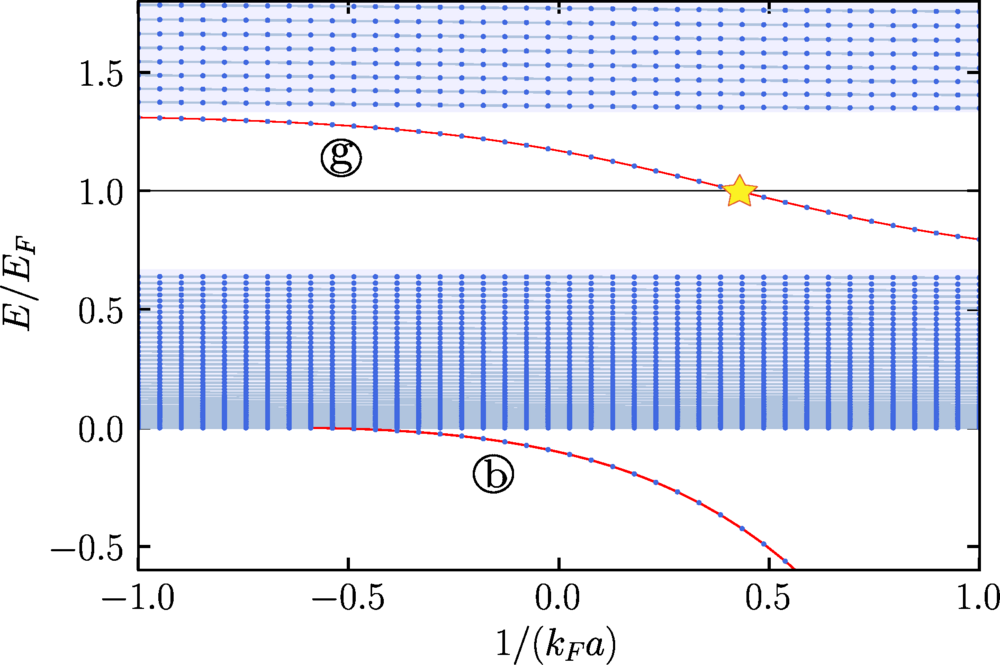

Impurity-induced mass gaps provide an important connection between the impurity and the surrounding fermions. When an impurity has any finite mass, something interesting happens—the impurity has a mass-induced energy gap, which is present at low energies, as given by the many-body spectrum near the Fermi surface.

This mass gap reflects the fact that the impurity cannot remain stationary, and as the mass of the impurity becomes larger, the mass gap becomes smaller. Once the impurity exceeds infinite mass, the gap will become zero and the system will return to the orthogonality catastrophe limit.

Therefore, as a result of this type of mass gap, Dizer and his co-workers have discovered a special type of in-gap state, which exists for any strength of interactions. The authors developed a way of thinking about the physical interactions occurring between an impurity and its surrounding medium that is more consistent with previous theories. This framework illustrates how these multiple states will be filled with electrons when the characteristics of the impurity and the nature of its medium allow for bound states to arise from attraction between the two constituents.

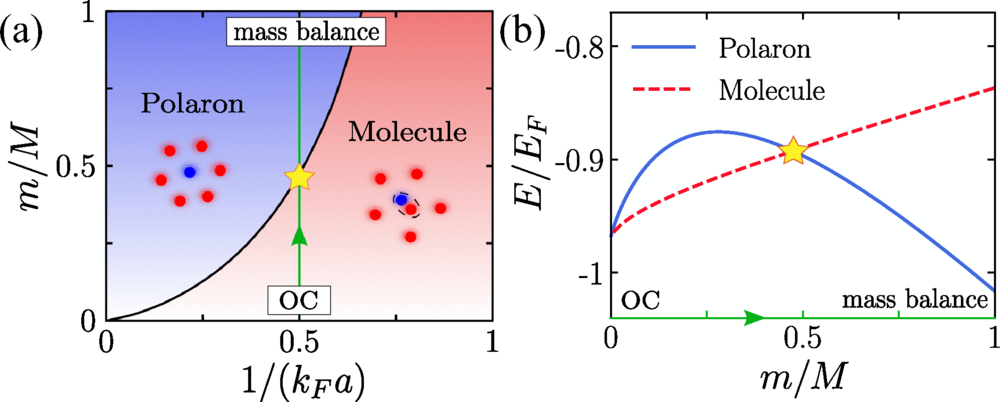

By understanding how these filled or empty states correspond to different types of hybrid states (polarons, molecular states, etc.), the authors are able to explain how the energy of these states varies with strength of interaction between the impurity and its surroundings.

This transition from one state to another appears to be similar to a first-order phase transition, as indicated by a sharp change in the slope of the ground-state energy at the crossing point of the two states. The exact point of this transition is dependent on the mass ratio of the impurity to that of the fermions that reside in its neighborhood. The more massive the impurity becomes, the narrower the gap becomes; consequently, when the gap closes, the in-gap state disappears and the distinction between polaron and molecular state vanishes, as was originally predicted by Anderson.

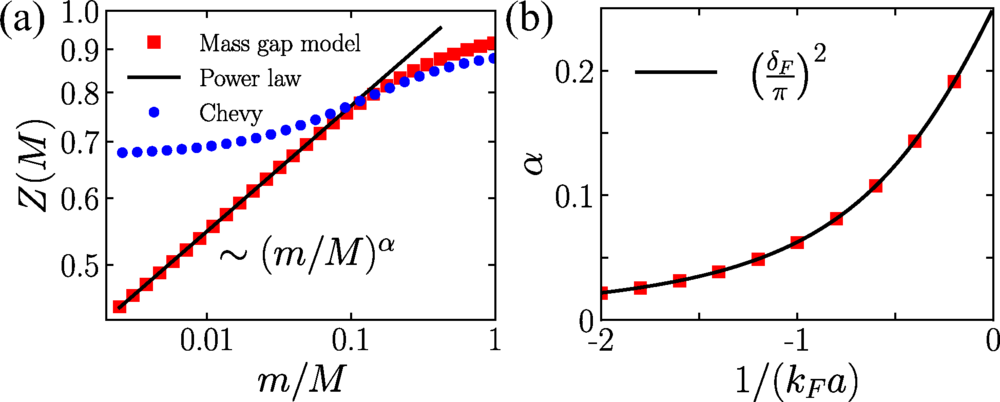

The same logic that applies to the transition from polaron to molecular state also applies to explaining why quasiparticles have a finite weight even though they are produced by mobile impurities. The orthogonality catastrophe results from the accumulation of very low-energy excitations that arise near the Fermi surface. When the mass of these impurities increases, their local gap region blocks low-energy excitations from existing on the Fermi surface.

As a result, the ground state of the system that interacts with the impurity retains a non-zero overlap with the Fermi sea. The model predicts that this overlap continues to decrease as the impurity becomes more massive, but is not discontinuous; the model also demonstrates that large mass imbalances, which are frequently found in ultracold atomic experiments, are capable of producing quasiparticles that are well defined.

According to Prof. Schmidt, “Our work opens new avenues for understanding and controlling quantum impurity phenomena and has broad implications for current research.” The authors hope to inspire new directions for both theoretical and experimental research in this area.

Research findings are available online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New unified theory connects two fundamental domains of modern quantum physics appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.