Time feels steady and familiar in daily life, but at the quantum level it becomes slippery. That puzzle now has a fresh twist thanks to new research led by physicists at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, or EPFL. The team, led by Professor Hugo Dil and first author Fei Guo, has found a way to measure how long certain quantum events actually take, without using an external clock.

“The concept of time has troubled philosophers and physicists for thousands of years, and the advent of quantum mechanics has not simplified the problem,” Dil says. “The central problem is the general role of time in quantum mechanics, and especially the timescale associated with a quantum transition.”

Some quantum processes unfold in just tens of attoseconds, or billionths of a billionth of a second. At that scale, light cannot cross the width of a virus. Measuring such short intervals is hard, partly because external timing tools can disturb the process itself.

“Although the 2023 Nobel prize in physics shows we can access such short times, the use of such an external time scale risks to induce artefacts,” Dil says. “This challenge can be resolved by using quantum interference methods, based on the link between accumulated phase and time.”

The EPFL team reports its findings in a peer reviewed physics journal, offering a new approach to one of the field’s oldest questions.

The researchers focused on photoemission, a process in which light hits a material and knocks electrons free. When an electron absorbs a photon and escapes, it carries subtle clues about what happened inside the material.

“These experiments do not require an external reference, or clock, and yield the time scale required for the wavefunction of the electron to evolve from an initial to a final state at a higher energy upon photon absorption,” Guo says.

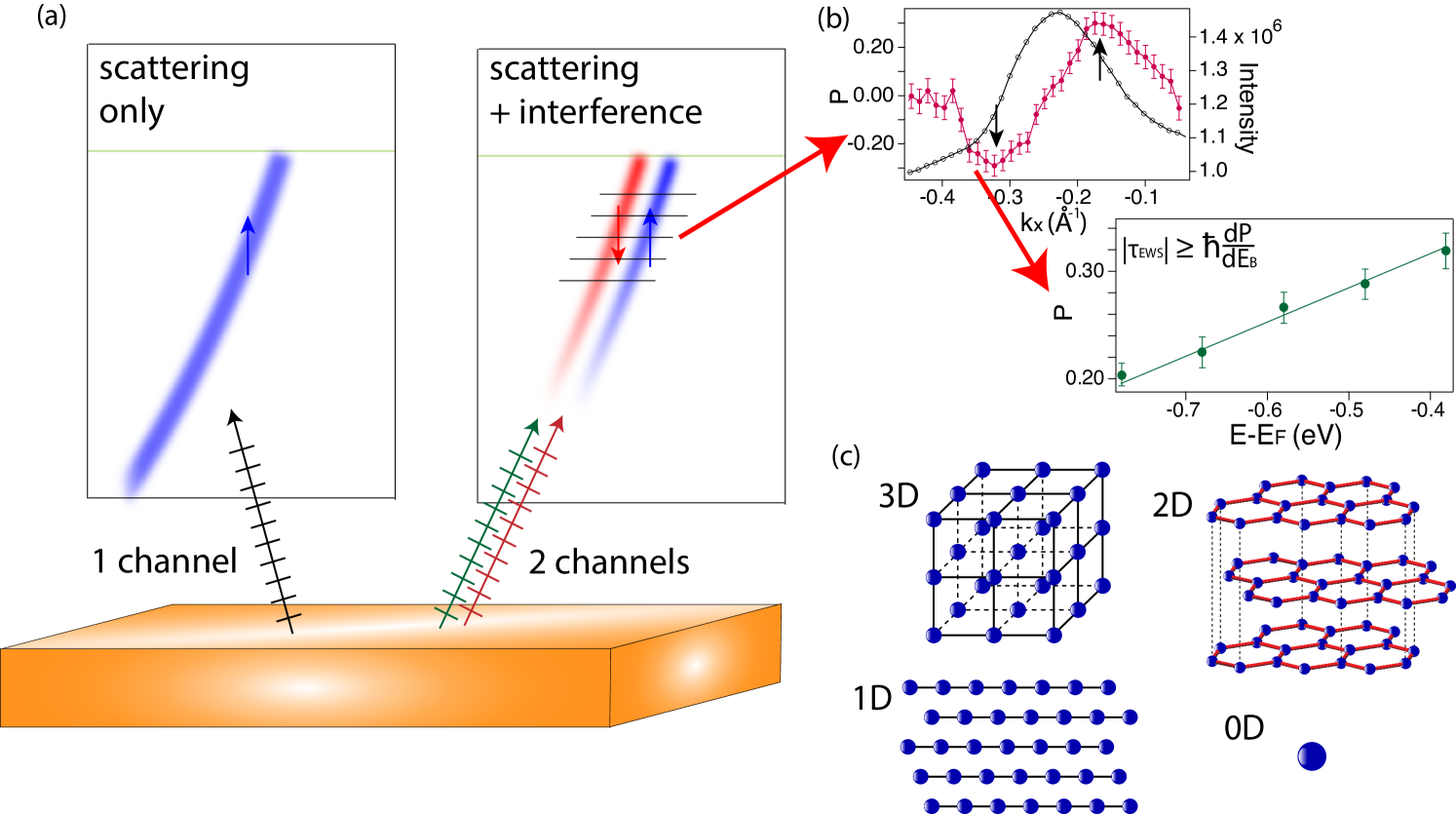

The key signal comes from electron spin. As electrons exit a material, their spin shifts in ways that depend on the quantum paths they took. Light can push an electron along several routes at once, and those routes interfere with each other. That interference leaves a fingerprint in the spin pattern of the emitted electron.

By tracking how spin changes with energy, the researchers could calculate how long the transition lasted. Time, in this case, is extracted from quantum phase rather than measured against a stopwatch.

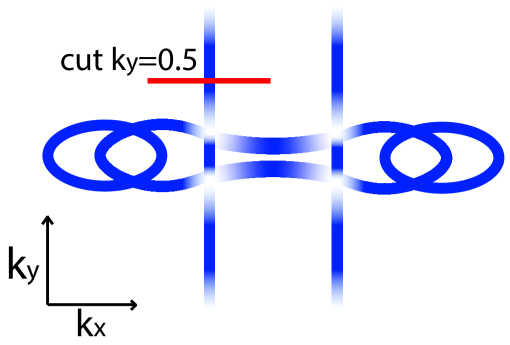

To do this, the team used spin and angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy, known as SARPES. The method uses intense synchrotron light to excite electrons and then records their energy, direction, and spin as they leave the material.

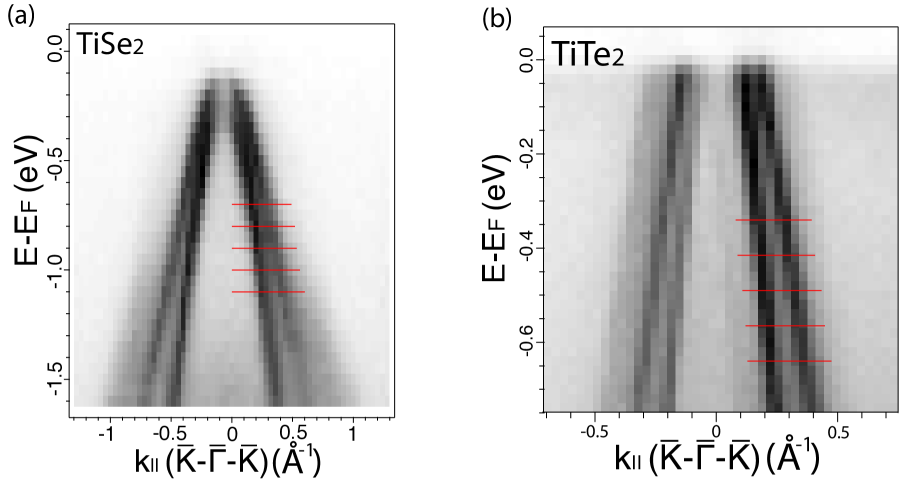

The study compared materials with very different atomic structures. Ordinary copper is fully three dimensional. Titanium diselenide and titanium ditelluride are layered materials that behave more like flat sheets. Copper telluride forms chain like structures that are close to one dimensional.

Those differences turned out to matter a lot. In three dimensional copper, the photoemission process lasted about 26 attoseconds. In the layered materials, the transition slowed to roughly 140 to 175 attoseconds. Meanwhile, in copper telluride, the most reduced structure tested, the time stretched beyond 200 attoseconds.

The trend was clear. As the atomic structure became simpler and less symmetric, the quantum transition took longer. Lower symmetry appeared to slow the process.

“Besides yielding fundamental information for understanding what determines the time delay in photoemission, our experimental results provide further insight into what factors influence time on the quantum level, to what extent quantum transitions can be considered instantaneous, and might pave the way to finally understand the role of time in quantum mechanics,” Dil says.

Physicists have debated the meaning of time in quantum mechanics for nearly a century. Many processes were long assumed to happen instantly. Over the past two decades, attosecond experiments have shown that this is not always true.

The new work adds a fresh perspective. Instead of treating time as an external background, the researchers pull time information directly from the quantum system itself. The delay is linked to how the phase of an electron’s wave changes with energy during photoemission.

Earlier studies hinted that strong electronic interactions might slow these transitions. The EPFL results suggest another major factor: symmetry. As symmetry decreases, whether by layering or chain like structure, the time delay grows.

That idea fits with examples from atomic physics, where more asymmetric systems show longer delays. It also explains why materials with similar chemistry but different structures can behave so differently in time sensitive measurements.

This work goes beyond settling a philosophical debate. Knowing how long quantum transitions last can help researchers design materials with precise electronic behavior. That matters for future quantum technologies, where control at the attosecond scale could improve sensors, computing elements, and communication systems.

The method also gives scientists a new tool for probing complex materials. By reading spin patterns, researchers can learn how electrons interact, how symmetry shapes behavior, and how quantum states evolve in real time.

More broadly, the findings suggest that time in quantum mechanics is not fixed. It depends on structure and symmetry. As those ideas are tested in more systems, they may reshape how physicists think about the flow of time at nature’s smallest scales.

Research findings are available online in the journal Newton.

The original story “Physicists measured time without a clock at the quantum scale” is published on The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Physicists measured time without a clock at the quantum scale appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.