Plastic waste surrounds daily life, from food containers and grocery bags to shampoo bottles and medical supplies. Much of it ends up buried or drifting into ecosystems because recycling it is slow, costly, and frustrating. A new study from chemists at Northwestern University suggests that problem may soon ease. Their research introduces a powerful nickel-based catalyst that can break down common plastics without the painstaking sorting that recycling systems depend on today.

The study describes a method that turns low-value plastic waste into useful liquid oils and waxes. Those products can later become fuels, lubricants, or everyday items like candles. The process focuses on polyolefins, plastics made from polyethylene and polypropylene that account for nearly two-thirds of global plastic use. These materials are everywhere, and they are also among the hardest to recycle.

“One of the biggest hurdles in plastic recycling has always been the necessity of meticulously sorting plastic waste by type,” said Tobin Marks, the study’s senior author at Northwestern. He said the new catalyst could remove that step for common plastics and make recycling more practical and affordable.

Most recycling systems rely on careful separation. Different plastics melt at different temperatures and behave differently during processing. Even small mistakes can ruin an entire batch. A little food residue or a stray piece of the wrong plastic can send tons of material straight to a landfill.

Polyolefins are especially stubborn. Their chemical structure consists of strong carbon bonds that resist breaking apart. “When we design catalysts, we target weak spots,” said Yosi Kratish, a co-corresponding author of the study. “But polyolefins don’t have any weak links. Every bond is incredibly strong and chemically unreactive.”

Because of that strength, many facilities simply shred polyolefins and melt them into lower-quality plastic. This downcycling limits how many times the material can be reused. Another approach involves heating plastic to extreme temperatures, sometimes over 400 degrees Celsius. While that method works, it consumes massive amounts of energy and drives up costs.

“Everything can be burned, of course,” Kratish said. “But we wanted an elegant way to add the minimum energy to get the most valuable product.”

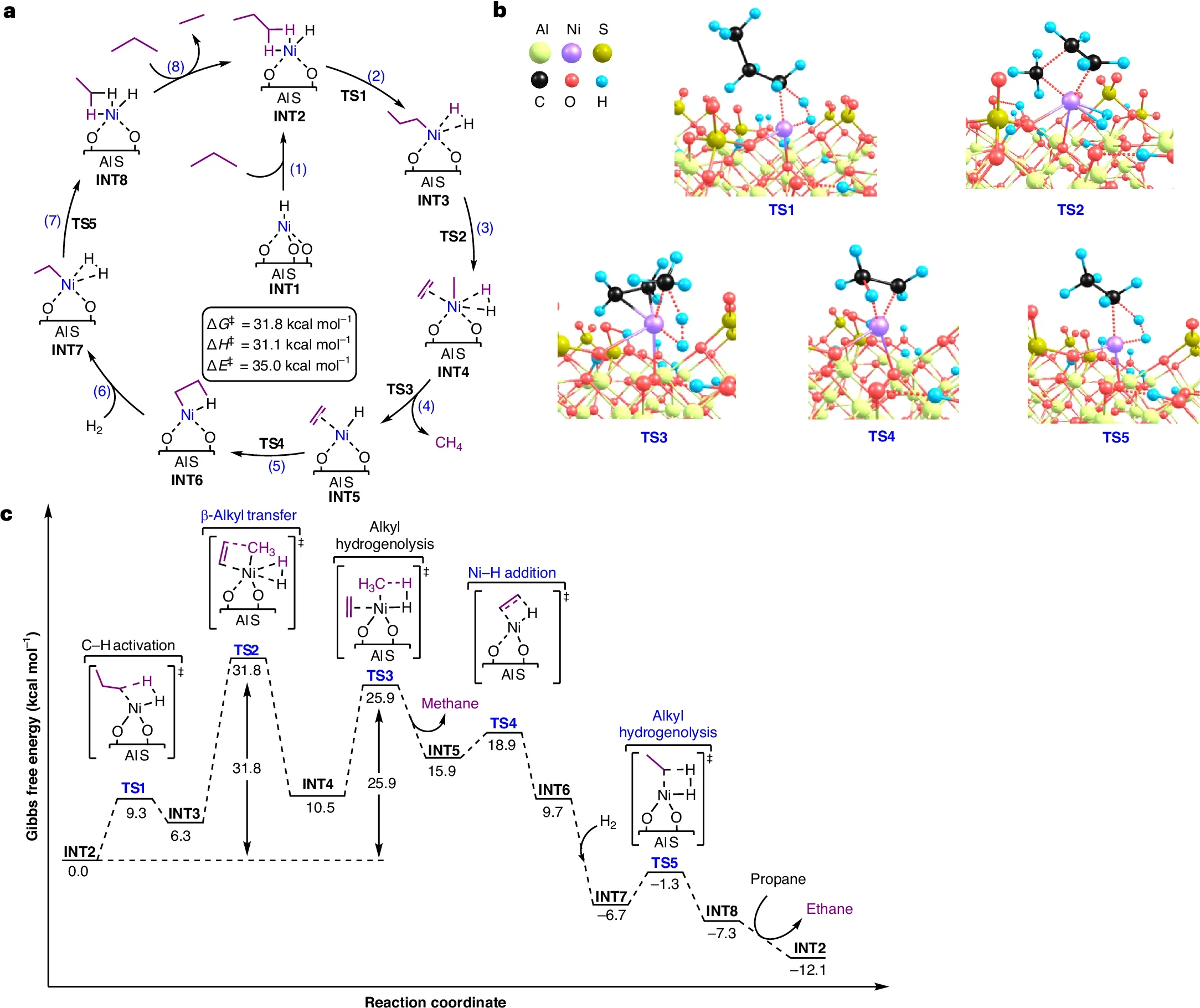

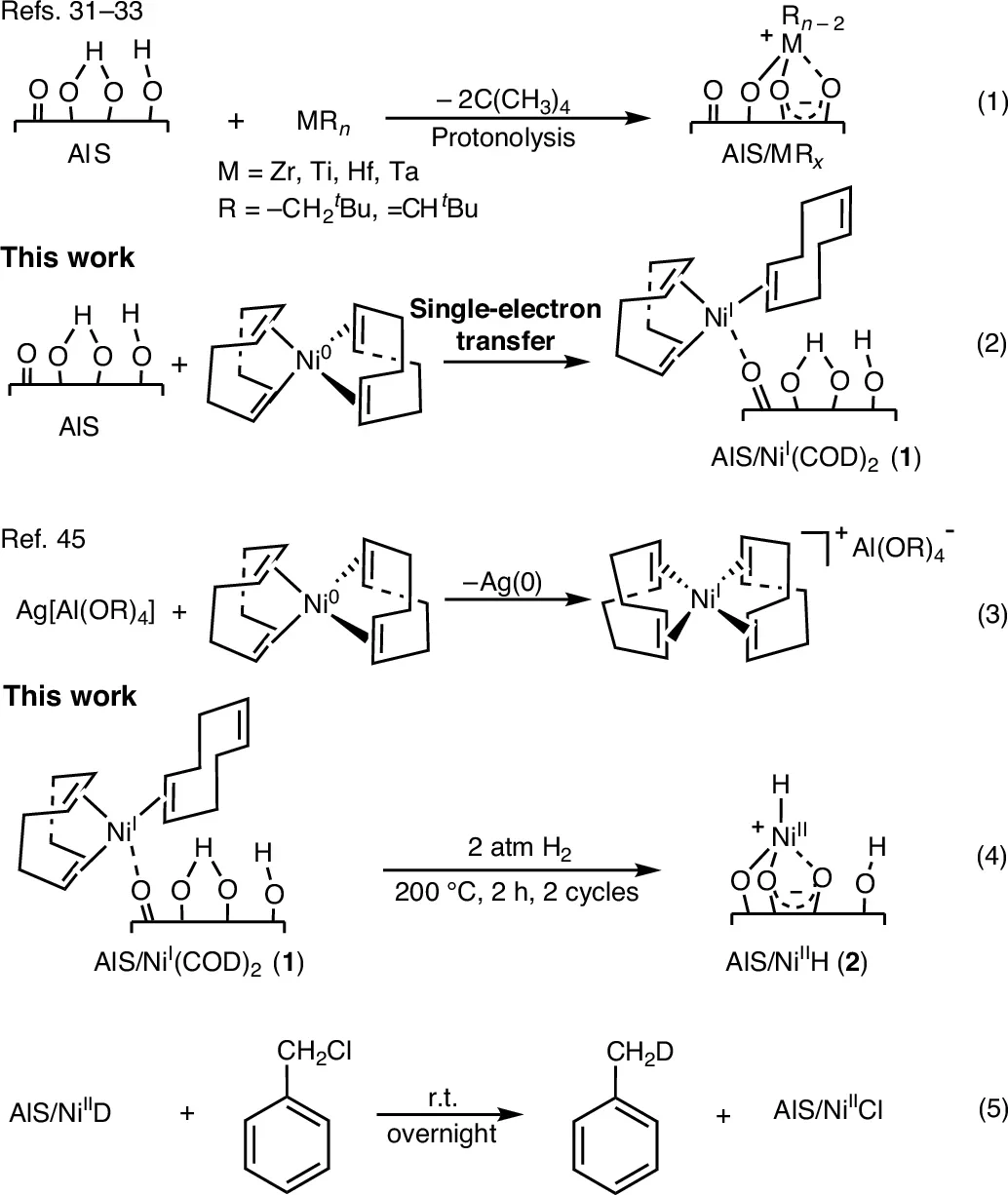

The Northwestern team turned to a process called hydrogenolysis. It uses hydrogen gas and a catalyst to break long plastic chains into smaller molecules. Existing hydrogenolysis methods rely on expensive metals like platinum or palladium and require harsh conditions. That makes them impractical on the scale needed for global plastic waste.

The new approach replaces those metals with nickel, which is far more abundant and affordable. Qingheng Lai, the study’s first author, said supply matters. “The polyolefin production scale is huge, but global noble metal reserves are limited,” he said. “We cannot use the entire metal supply for chemistry.”

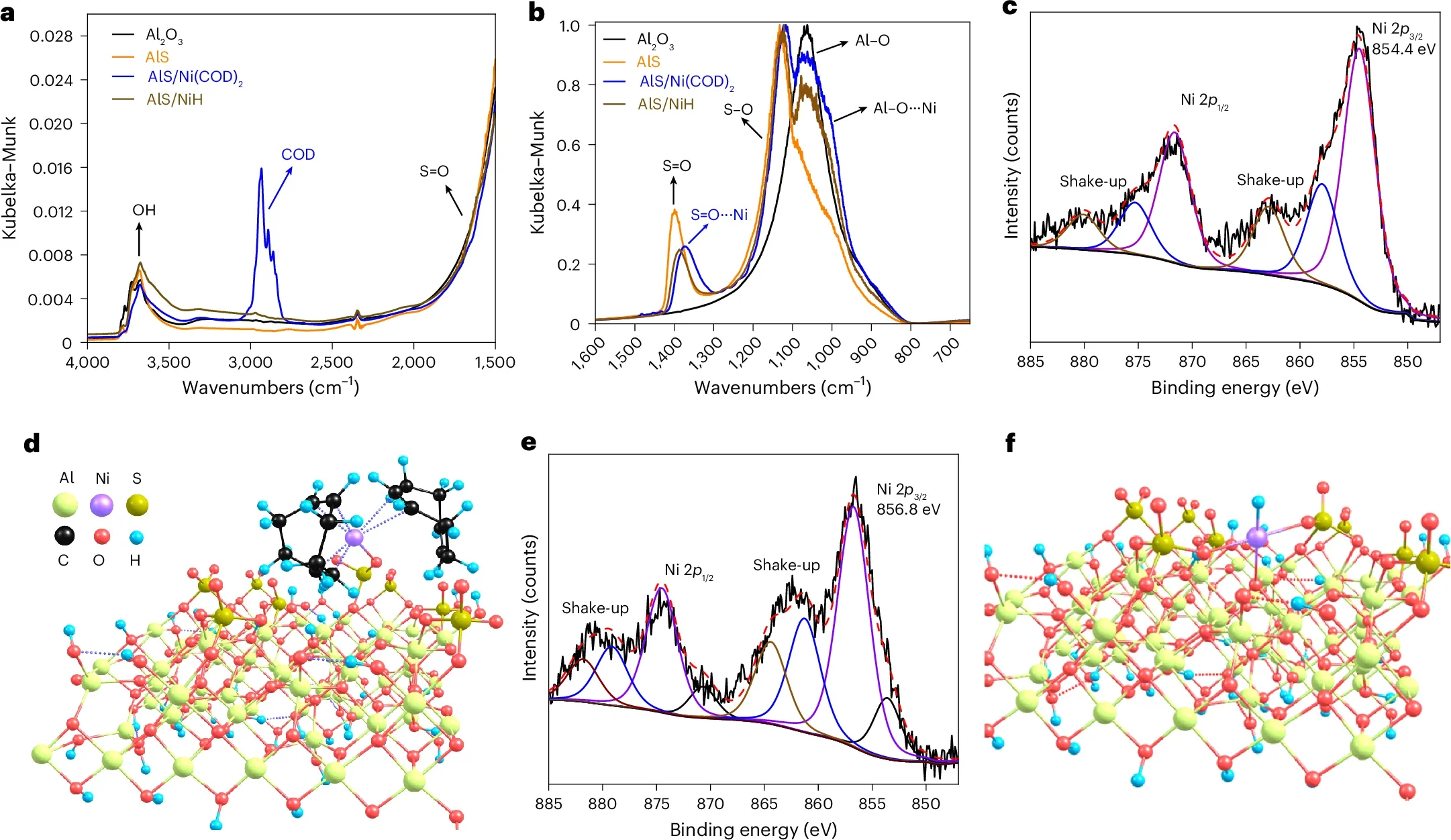

What sets this catalyst apart is its single-site design. Each nickel atom acts alone instead of clustering with others. This allows the catalyst to behave like a precise cutting tool instead of a blunt force. It selectively breaks certain carbon bonds while leaving others intact.

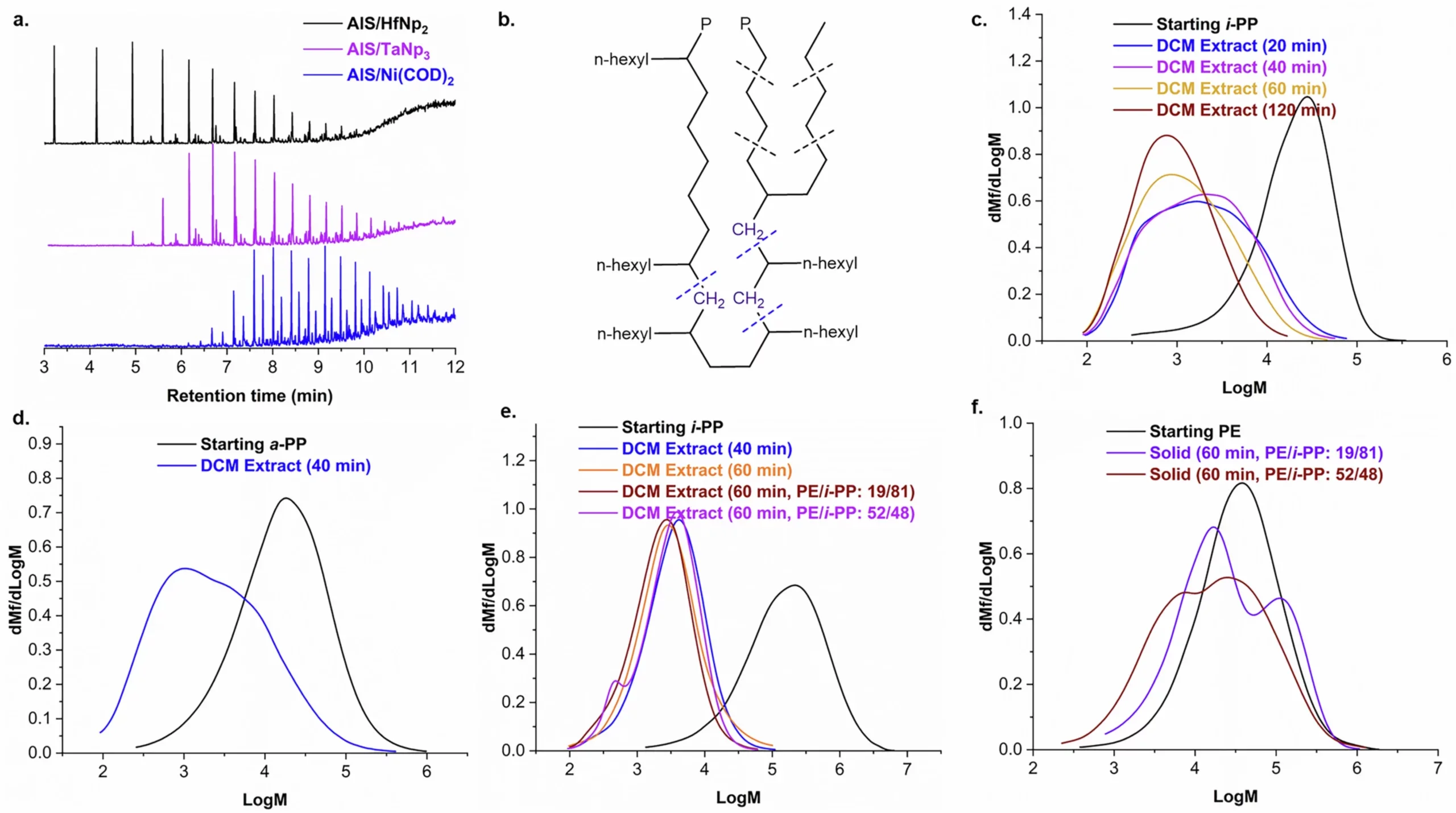

That precision allows the catalyst to target branched polyolefins, such as isotactic polypropylene, even when mixed with unbranched plastics. In effect, it separates plastics chemically rather than mechanically.

Tests showed the catalyst works under milder conditions than previous systems. It operates at temperatures about 100 degrees lower and uses half the hydrogen pressure of similar methods. It also requires much less catalyst material while delivering higher activity.

“We are winning across all categories,” Kratish said.

The products formed during the reaction are not useless scraps. The solid plastic turns into liquid oils and waxes that have higher value and broader uses. These liquids can serve as building blocks for new materials or energy products, helping close the loop on plastic use.

Another key advantage is durability. The catalyst remains stable through repeated cycles and can be regenerated using a simple and inexpensive treatment. That reusability is critical for any future industrial application.

One of the most surprising findings involved contamination. Polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, is a plastic widely used in pipes and flooring. It looks similar to other plastics, but when heated, it releases hydrogen chloride gas that usually destroys catalysts. Because of that, PVC contamination often makes recycling impossible.

In this study, PVC did not shut the process down. Instead, it made it faster. Even when PVC made up a quarter of the plastic mixture, the catalyst continued working and showed improved performance.

“Adding PVC to a recycling mixture has always been forbidden,” Kratish said. “But apparently, it makes our process even better. That is crazy.”

This unexpected result suggests the method could handle real-world plastic waste far better than existing technologies. Mixed and dirty waste streams are the norm, not the exception.

The scale of the plastic problem is immense. Industry produces more than 220 million tons of polyolefin plastics each year. Yet global recycling rates remain shockingly low, often below 10 percent. Much of the waste persists for decades, slowly breaking into microplastics that harm wildlife and enter food chains.

By removing the need for sorting and tolerating contamination, the nickel catalyst addresses two major barriers at once. It offers a path toward treating plastic waste as a resource instead of a burden.

The research brought together experts from multiple institutions, including Purdue University and Ames National Laboratory. The team believes the work could guide the next generation of recycling systems.

This discovery could reshape industrial recycling by allowing mixed plastic waste to be processed together, cutting labor, time, and cost. It could reduce landfill use and limit plastic pollution in the environment.

The ability to turn waste into valuable products may encourage wider adoption of recycling technologies.

Over time, this approach could help build a more circular economy where plastics are reused instead of discarded.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Powerful catalyst could make mixed plastic recycling a reality appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.