Debangshu Banerjee, a recent graduate of the Centre for Earth Observation Sciences at the University of Manitoba, with Dr. Karen Alley of the same center and Dr. David Lilien of Indiana University Bloomington., and partner institutions have uncovered a clear pattern behind the slow unraveling of a critical Antarctic ice shelf.

Their findings were published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface and form part of the Thwaites Amundsen Regional Survey and Network, a core project within the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a major U.S.-U.K. research effort.

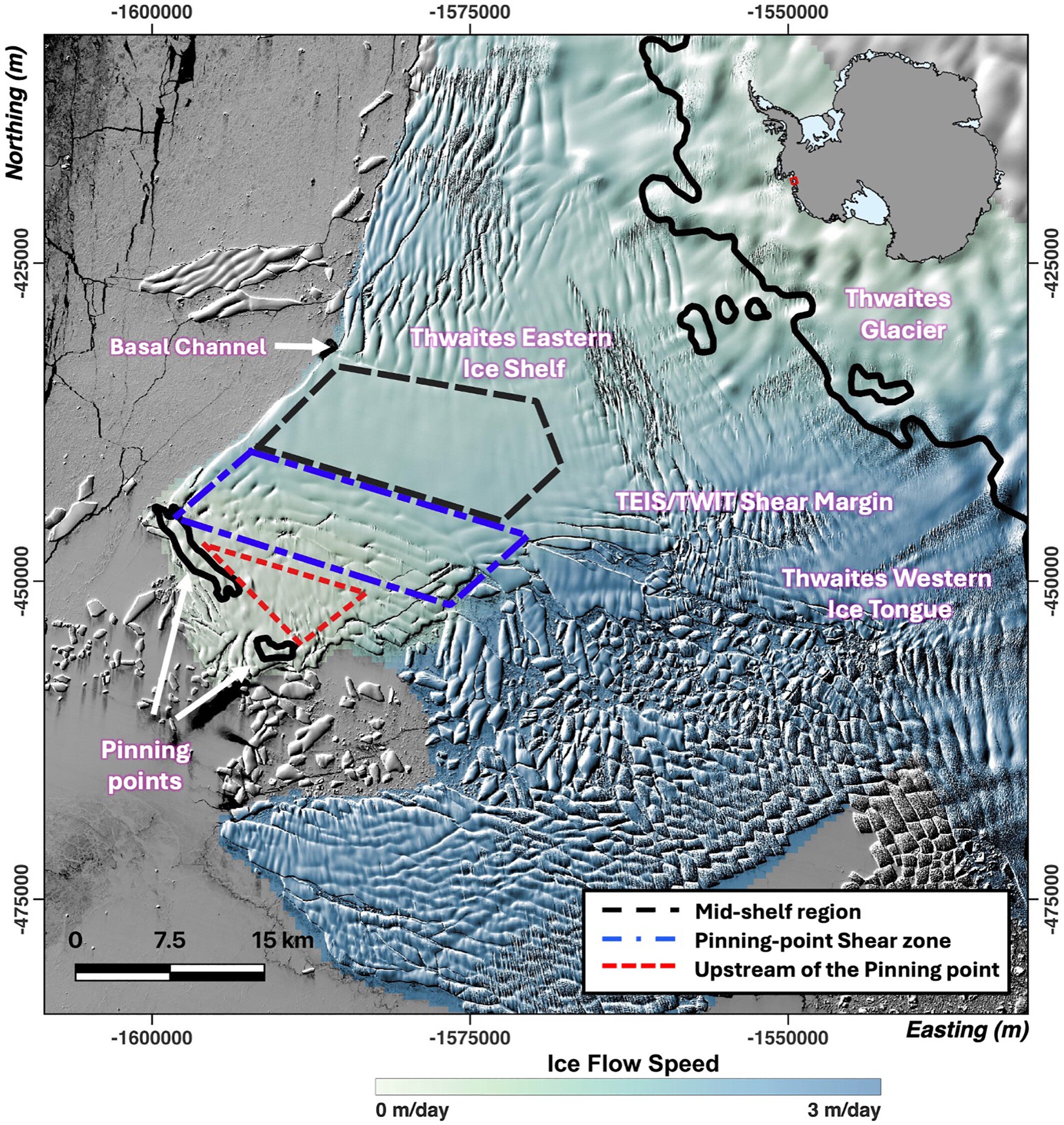

The focus of the study is the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf, a floating extension of West Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier. Thwaites holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by about 65 centimeters. Its rapid change has earned it the nickname “Doomsday Glacier,” yet the new research shows that its weakening follows an organized sequence rather than random collapse.

For decades, the eastern ice shelf was partly held in place by a rocky ridge on the seafloor at its northern edge. This feature, known as a pinning point, acted like a brake. It resisted ice flow and helped stabilize the glacier upstream. Over the past 20 years, that stabilizing role has steadily faded.

To understand how this happened, the research team analyzed satellite images, ice flow speed data, and GPS measurements collected between 2002 and 2022. They tracked the growth of cracks within a narrow shear zone just upstream of the pinning point. This region sits where different parts of the ice shelf move at different speeds, making it vulnerable to stress.

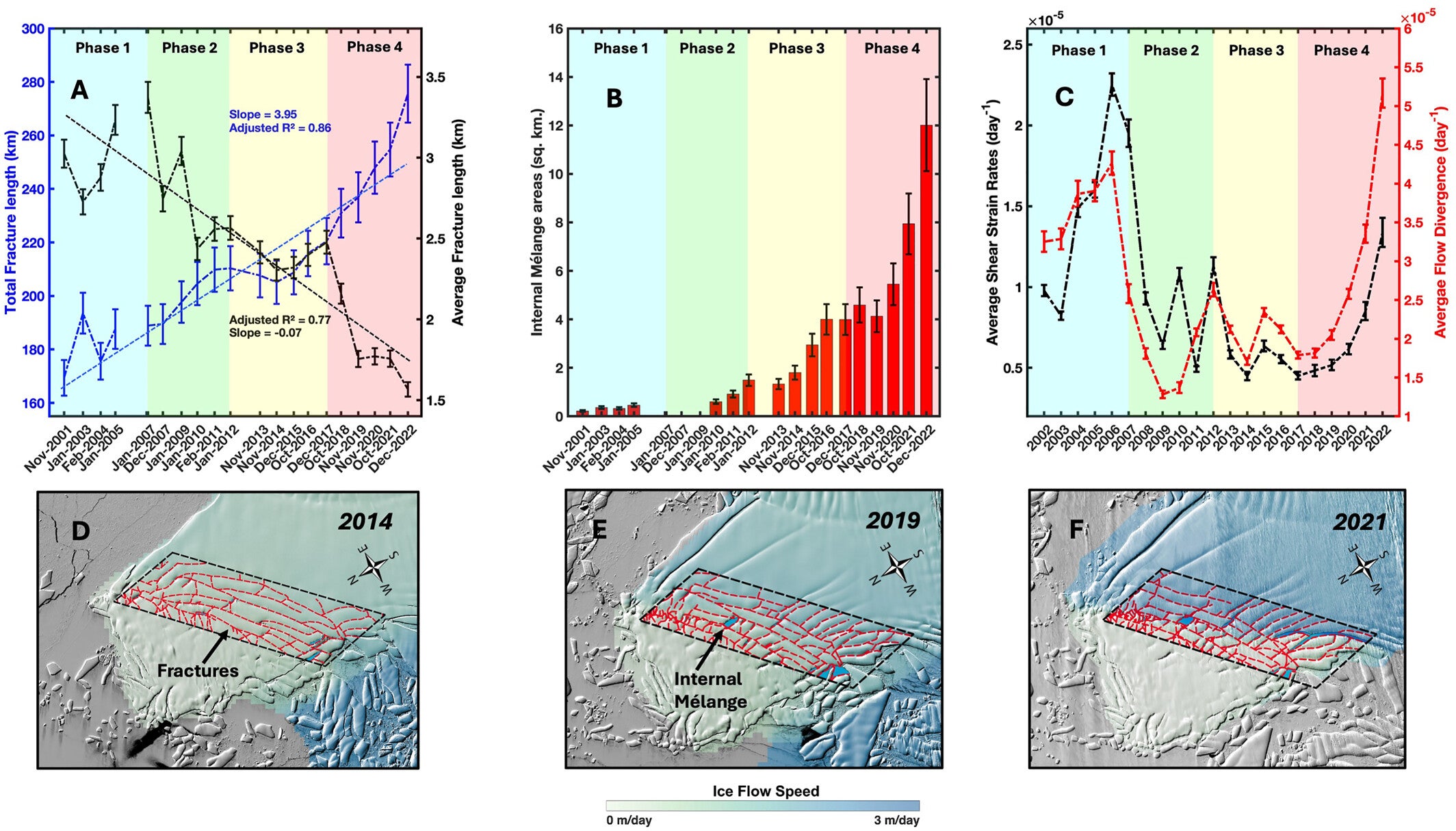

The data revealed that fractures expanded in a predictable way. Total crack length in the shear zone increased from about 165 kilometers in 2002 to more than 330 kilometers by 2021. At the same time, the average length of each crack dropped by more than half. This shift shows that the ice did not fail through a few dramatic breaks. Instead, it weakened as many smaller cracks filled in the shelf.

“Our research team identified four stages in this process. From 2002 to 2006, the western portion of the glacier sped up and dragged the eastern shelf forward. This motion stretched ice farther upstream while squeezing ice near the pinning point. Large, flow-aligned cracks grew during this period,” Banerjee told The Brighter Side of News.

Between 2007 and 2011, the shear margin connecting the eastern and western ice shelves collapsed. Once that connection broke, the eastern shelf slowed. Stress concentrated around existing fractures near the pinning point rather than being spread across the shelf.

From 2012 to 2016, long cracks continued creeping eastward. Speeds stayed relatively steady, but the link between the ice shelf and its rocky anchor weakened further. By around 2017, the system entered a final phase. Cracks cut across most of the shelf’s width, and the ice upstream began to accelerate again.

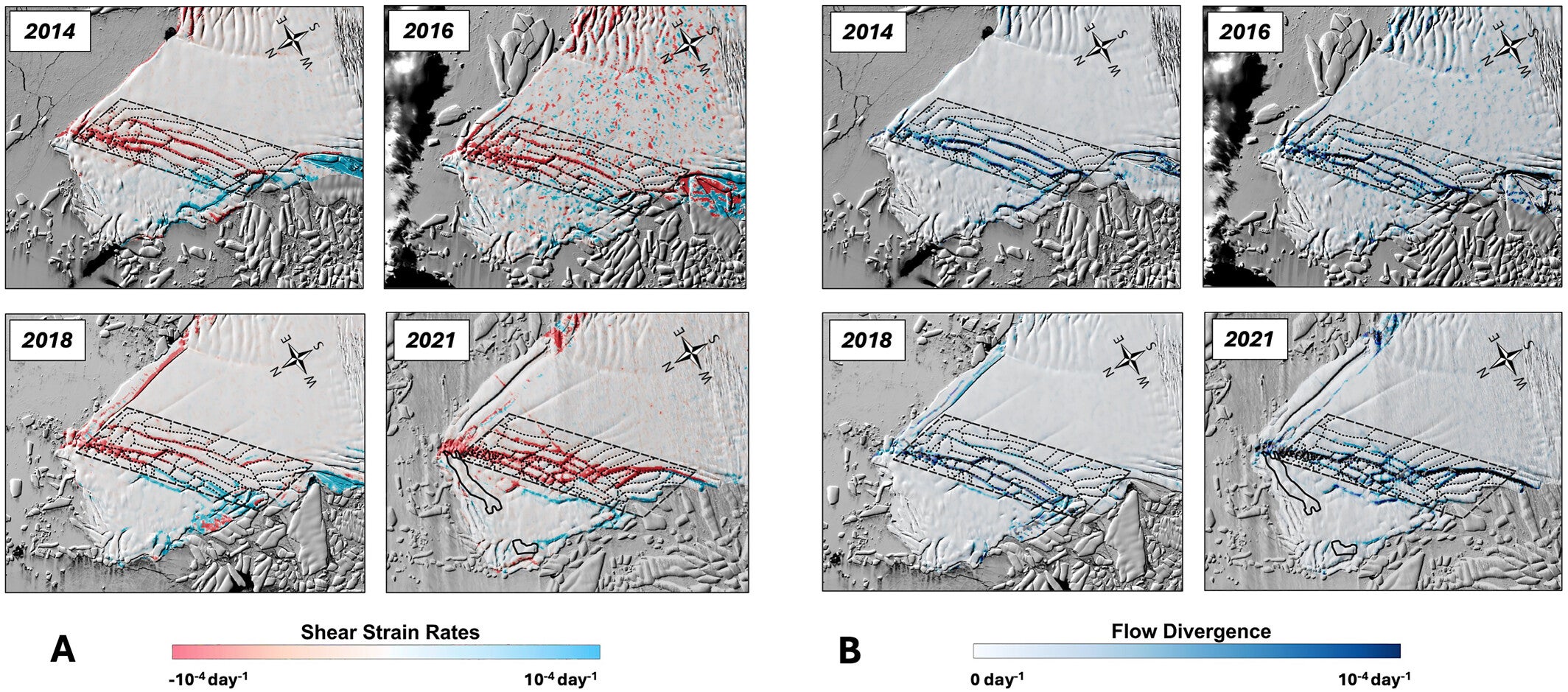

One of the most important findings is the discovery of a feedback loop between cracking and ice motion. As fractures grow, they concentrate stress. That added stress speeds up ice flow. Faster flow then creates new fractures, which further weaken the shelf.

GPS stations placed on the ice shelf between 2020 and 2022 captured this process in real time. During the austral winter of 2020, the instruments recorded a sharp jump in ice acceleration. Satellite images from the same period showed a new boundary forming between slow and fast-moving ice. That boundary migrated upstream as a major rift widened.

The researchers observed that changes near the pinning point spread across the shelf at speeds of up to about one kilometer per year. This showed that damage in a small area could influence ice motion far upstream, even without sudden surface melting.

The fractures themselves formed in two stages. First came long cracks aligned with the direction of flow. Later, dense fields of shorter cracks appeared at right angles to the flow. This second stage marked a shift from compression to stretching across much of the shelf and coincided with the strongest acceleration.

Early in the record, the pinning point helped stabilize the ice shelf by resisting motion. Over time, thinning ice reduced its grip. What had once been a single grounded feature split into smaller ice bumps, with ice flowing between them. Eventually, stress around this area promoted cracking instead of preventing it.

The study shows that the pinning point did not simply lose influence. It changed roles. By the later stages, it had become a focal point for damage. “The accumulation of structural damage concentrates stress and speeds up ice flow,” the authors wrote, reinforcing the feedback cycle that drives further weakening.

Similar behavior has preceded the collapse of other Antarctic ice shelves. The researchers point to past examples where stabilizing features later became the starting points for failure. Thwaites sits on a seafloor that slopes downward inland, a configuration known to favor unstable retreat once it begins.

The findings help clarify how ice shelves fail and why some collapses accelerate suddenly after years of slow change. For scientists, the detailed fracture record offers valuable data for improving models that predict sea level rise. Many existing models focus on melting alone. This study shows that internal stresses and fracture feedbacks can play a dominant role.

For society, the work underscores why Thwaites Glacier remains a global concern. Even small increases in ice flow from this region can add measurable amounts to sea levels each year. Better forecasts can help coastal planners and governments prepare for future risks. The research also provides warning signs to watch for on other Antarctic ice shelves that may be nearing similar tipping points.

Research findings are available online in the journal JGR Earth Surface.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Quiet cracking is destabilizing Antarctica’s Doomsday Glacier leading to irreversible collapse appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.