Reaching net zero carbon emissions will not bring quick relief from extreme heat. New research shows that once the world stops adding carbon dioxide, dangerous heatwaves will still come often and last longer, not for decades but for at least 1,000 years.

The study, published in Environmental Research: Climate, looked beyond the usual short-term forecasts. It asked what happens after emissions fall to zero and the climate settles. The answer is blunt. Net zero is vital, but it does not switch the climate back to normal.

Heatwaves were measured as runs of at least three days above the hottest 10 percent for a given time of year, using 1850 to 1900 as the baseline. By that yardstick, extreme heat has already grown across most regions since the 1950s. Human-driven warming is the main cause, not natural swings in weather.

Here is the core result. The later the world reaches net zero, the worse heatwaves become, and the difference never disappears. Waiting even five years adds lasting harm.

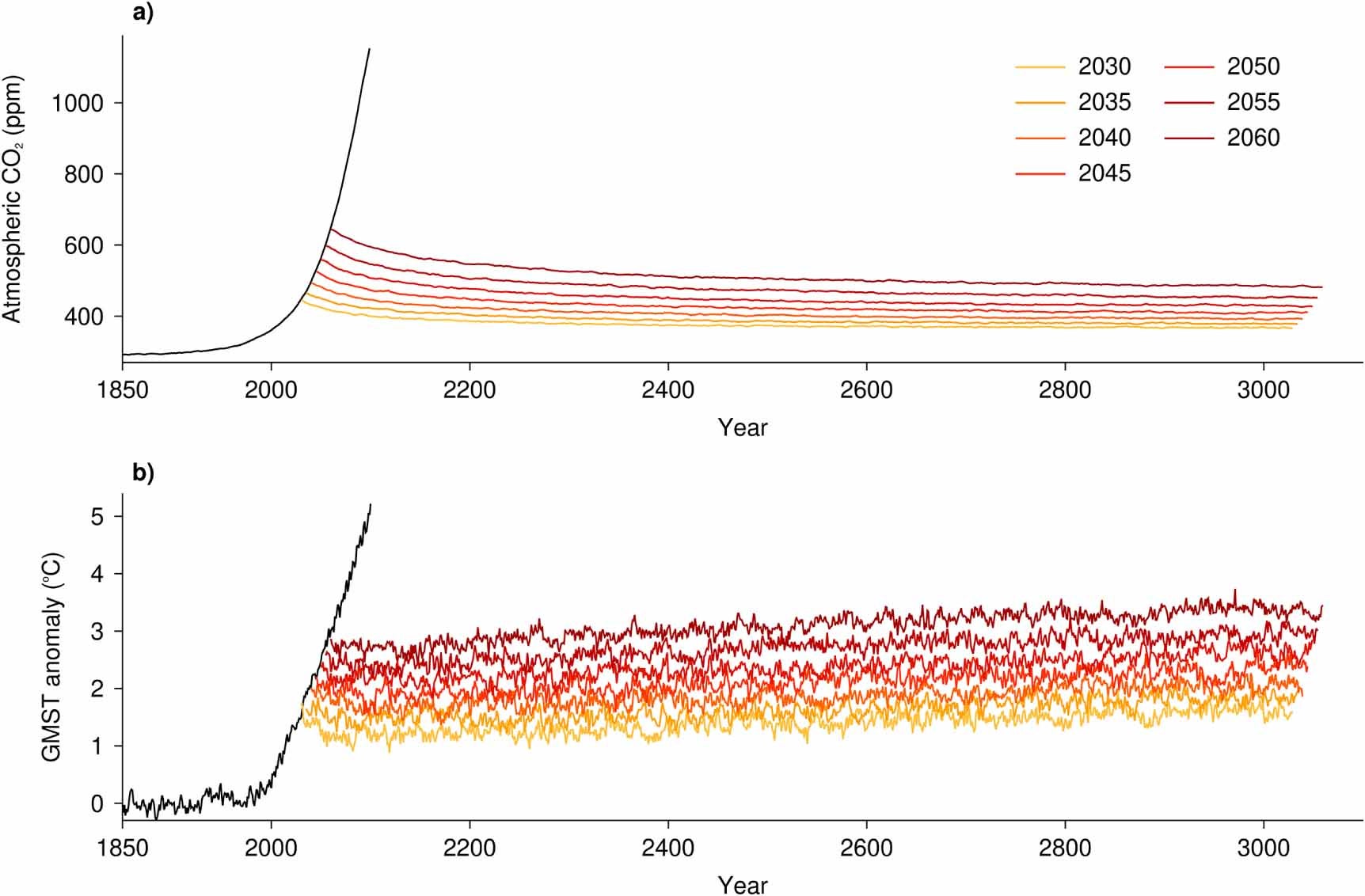

To study a net zero world, scientists used the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator, called ACCESS-ESM1-5. Seven simulations branched from a high-emissions path between 2030 and 2060, in five-year steps. At each branch point, carbon dioxide emissions fell to zero and stayed there for 1,000 years.

The model allowed forests and oceans to keep soaking up or releasing carbon, so atmospheric levels declined slowly. Other gases and particles were set at preindustrial values. By design, global temperature barely changed across the next millennium, about 0.03 degrees Celsius per century.

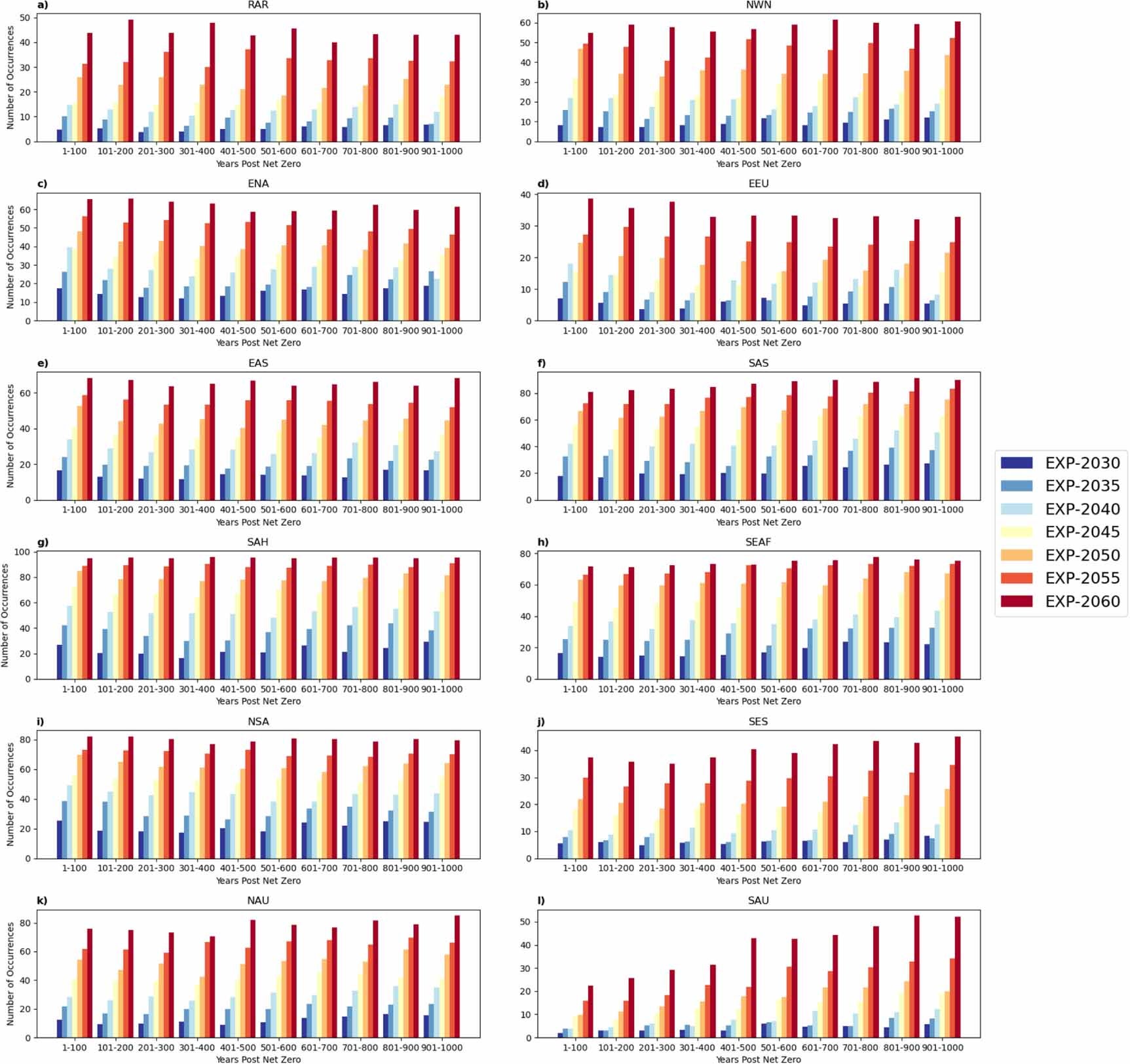

Researchers tracked three features of heatwaves: how many days per season they occurred, how long each event lasted, and how much extra heat they delivered above the old 90th percentile line. They studied 12 land regions defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and compared early and late paths.

This approach let the team test a simple idea. If average temperature stays high, what happens to daily extremes? They found the extremes stay high too.

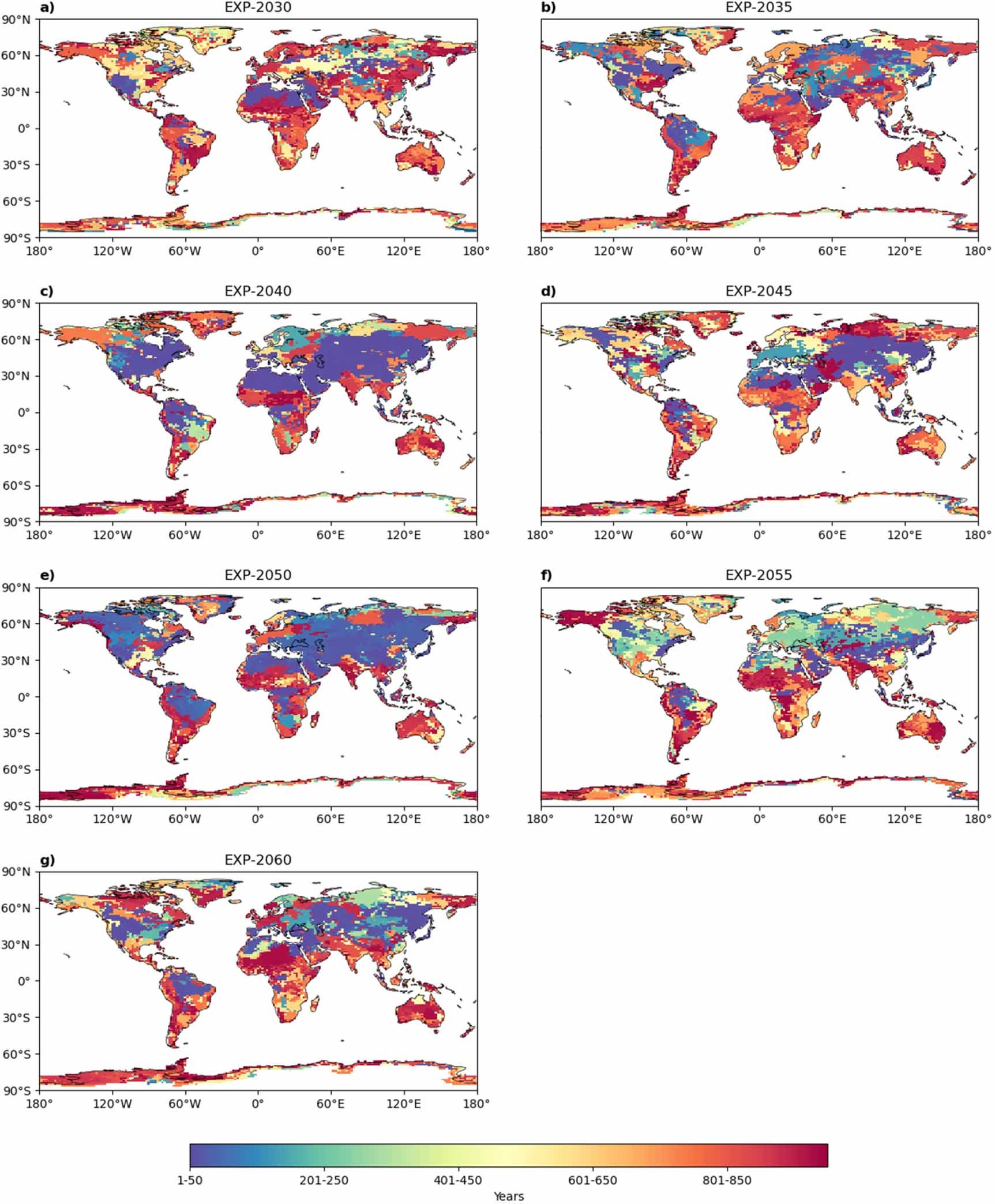

Midway through the millennium, the gap between early and late action is stark. A world that waits until 2060 to reach net zero faces many more heatwave days each summer than one that stops in 2030.

In Central Africa and northern South America, the later timeline adds about 70 extra heatwave days per season. Southern Asia and the Middle East gain roughly 50 to 80 days. Australia picks up 40 to 50 days. Regions north of 30 degrees latitude gain 15 to 45 days.

Length and strength follow the same pattern. Pushing net zero to 2060 brings longer spells and more excess heat. In parts of Africa, the Middle East and the northern Andes, summers start to resemble one long preindustrial heatwave.

Waiting also erodes the benefit step by step. Reaching net zero in 2040 is clearly better than 2060, and still worse than 2030. Even a five-year delay from 2055 to 2060 leaves a measurable scar that lasts through the millennium.

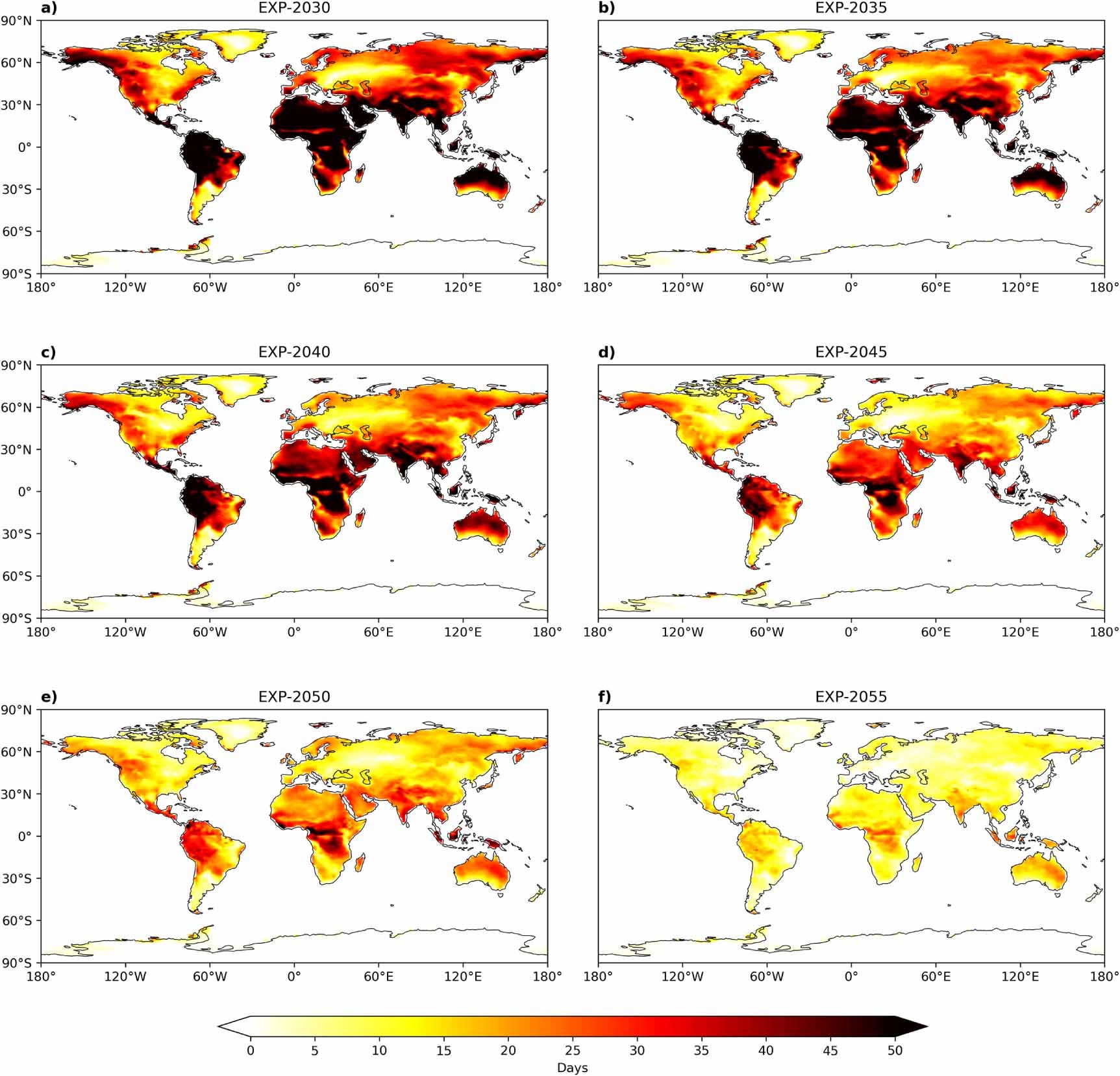

The team compared these futures with two common targets, a world that has just crossed 2 degrees Celsius of warming and one that has reached 3 degrees while still heating up.

If emissions stop early, heatwaves are fewer than in a transient 2-degree world. Across Africa, tropical South America and the Middle East, early action cuts 40 to 60 heatwave days per year compared with a planet that is still warming to 2 degrees.

Delay flips that story. When net zero arrives in 2055 or 2060, heatwaves become more common than in a newly 2-degree world. Some regions add 10 extra days per year, while others add 40 or more across sub-Saharan Africa, southern Asia and Australia.

Against a 3-degree world, net zero still looks safer overall. But the edge shrinks as action slips. In parts of Australia, southern Asia and Africa, a 2060 net zero path can even bring more heatwave days than a planet warming through 3 degrees.

Across all 12 regions, earlier net zero always means fewer heatwave days over the next 1,000 years. Delaying from 2030 to 2060 often doubles the seasonal count.

Several Southern Hemisphere regions keep worsening through time, not just staying high. South Asia, southeast Africa, southeast South America and much of Australia all show long-term upward trends in heatwaves under every timeline.

Elsewhere, the best outcome is a plateau at levels far above the past. Only Eastern Europe and East North America show hints of slow decline in some late paths, and those changes may take centuries to notice.

Records also get shattered. The historical “worst season” happened about once every 160 years. In a 2030 net zero world, similar seasons strike 5 to 20 times per century. In a 2060 world, they arrive 30 to 90 times per century, close to every year.

Low-latitude areas face the greatest danger. Small shifts in average warmth there cause a large jump in days above the old extreme line. People and ecosystems adapted to narrow temperature ranges are hit hardest.

Global temperature does not fall in any of the simulations, even after 1,000 years. That keeps daily extremes locked in.

Several forces likely help. The Southern Ocean keeps warming, sea ice shifts and there is no active carbon removal in the scenarios. Natural drawdown alone does not cool the planet back.

Professor Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick of the Australian National University led the study. “While our results are alarming, they provide a vital glimpse of the future, allowing effective and permanent adaptation measures to be planned and implemented,” she said.

University of Melbourne co-author Dr. Andrew King warned that delay brings danger, especially near the equator. “This is particularly problematic for countries nearer the equator,” he said. “A heatwave that breaks records can be expected at least once every year or more often if net zero is delayed until 2050 or later.”

He added that planning cannot wait. “Investment in public infrastructure, housing, and health services to keep people cool and healthy during extreme heat will very likely look quite different under earlier versus later net zero,” King said. “This adaptation process is going to be the work of centuries, not decades.”

The findings set a clear agenda. Rapid cuts buy relief that lasts for centuries. Every year of delay fixes a higher level of risk into the climate system. That reality should guide energy policy, city design and health planning.

Expect heat to shape daily life. Buildings need cooling that is efficient and affordable. Power grids must handle heavy demand. Hospitals and outdoor workplaces need stronger protections. Early warning systems and shade in public spaces will save lives.

Justice also matters. The harshest impacts fall on places with fewer resources to adapt. Faster action narrows that gap and prevents widening health and economic losses.

For science, the work shifts attention past 2100. It replaces wishful thinking with long-range evidence and highlights the need for research on safe carbon removal and heat resilience. The core message is simple. Reaching net zero sooner locks in a safer future, even if perfection remains out of reach.

Research findings are available online in the journal Environmental Research: Climate.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Record-breaking heatwaves will persist for 1,000 years, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.