After a long trail race, some of your red blood cells may not bend the way they should.

That matters because red blood cells have a tight job description. They ferry oxygen, nutrients, and waste through vessels that can be narrower than the cells themselves. To do it, they have to stay flexible.

A new study in the American Society of Hematology journal Blood Red Cells & Iron reports that extreme endurance running can leave those cells stiffer and more chemically battered, with the strongest effects occurring after the longest event in the study.

“Participating in events like these can cause general inflammation in the body and damage red blood cells,” said the study’s lead author, Travis Nemkov, PhD, associate professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Colorado Anschutz. “Based on these data, we don’t have guidance as to whether people should or should not participate in these types of events; what we can say is, when they do, that persistent stress is damaging the most abundant cell in the body.”

Researchers collected blood from 23 endurance-trained runners right before and immediately after two world-class events in the Alps: the Martigny-Combes à Chamonix race, or MCC (40 kilometers, elevation gain 2,300 meters), and the Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc, or UTMB (171 kilometers, elevation gain 10,000 meters).

The MCC group included 11 runners (five women, six men) with an average age of 35.7 ± 8.6 years. The UTMB group included 12 runners (four women, eight men) with an average age of 38 ± 6.4 years.

The team did not just run standard blood counts. They paired traditional hematology and “hemorheology” tests with a broad set of molecular measurements, using multi-omics to track thousands of molecules in both plasma and red blood cells.

In plasma and red cells combined, the dataset included hundreds to more than a thousand proteins, hundreds of lipids, hundreds of metabolites, and a handful of trace elements. Specifically, the study reports 440 or 1105 proteins, 659 or 647 lipids, 197 or 271 metabolites, and 8 or 6 trace elements in plasma or red blood cells, respectively.

The point of that molecular haul was to map what stress looks like inside a cell that cannot easily repair itself. Red blood cells lack nuclei and organelles, so they cannot replace damaged proteins and lipids through new synthesis.

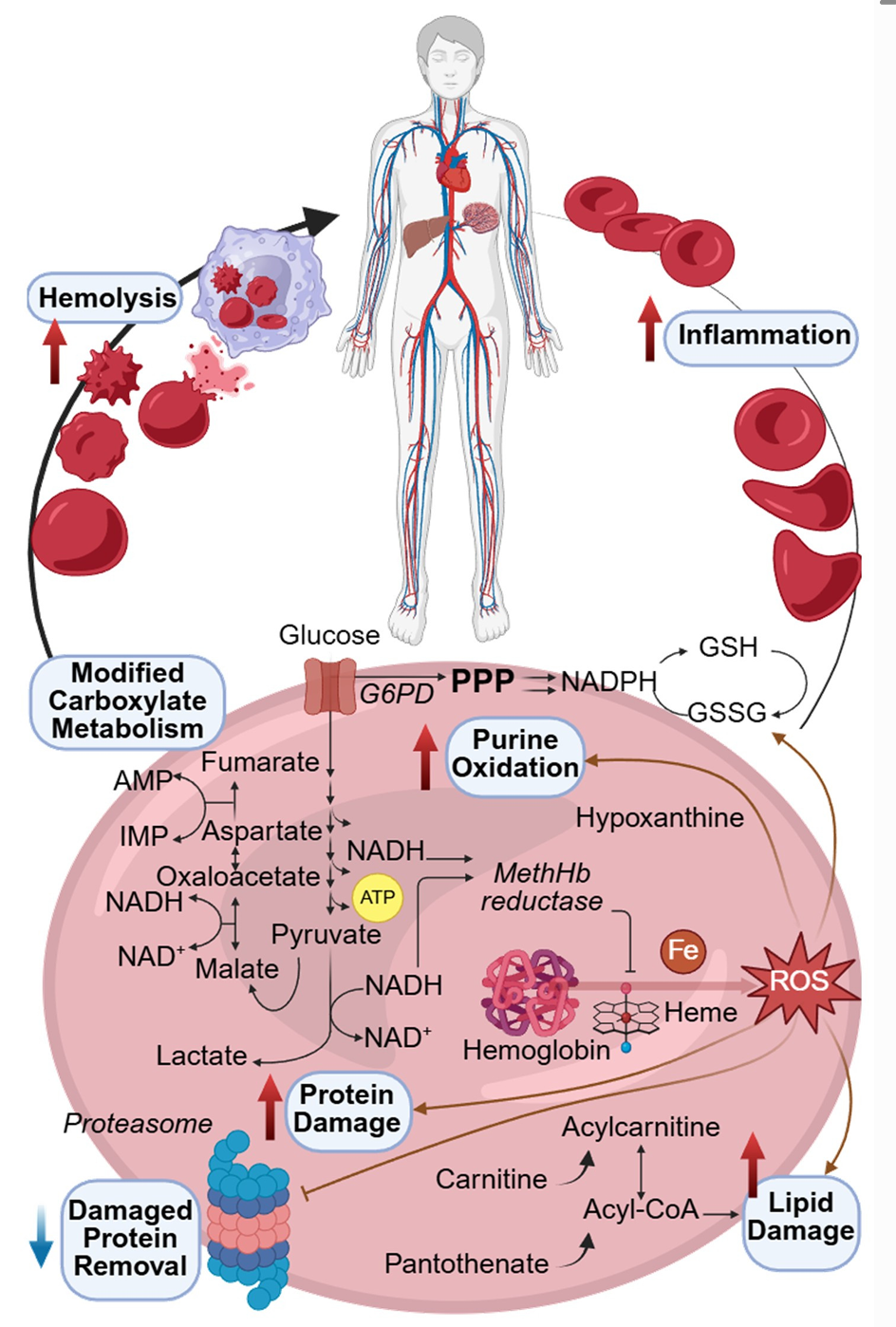

Signs of red blood cell stress appeared even after the 40-kilometer race. The study describes evidence of damage driven by both mechanical and molecular forces.

Mechanically, the authors point to running-related changes in fluid pressure as cells circulate. Molecularly, they link changes to inflammation and oxidative stress, a state in which antioxidant defenses are low compared with damaging molecules.

The longer UTMB race pushed those patterns further. The researchers write that distance and time under load dictated how much remodeling the red blood cells underwent, with the 171-kilometer race crossing a threshold where the harm became easier to measure.

“At some point between marathon and ultra-marathon distances, the damage really starts to take hold,” Nemkov said. “We’ve observed this damage happening, but we don’t know how long it takes for the body to repair that damage, if that damage has a long-term impact, and whether that impact is good or bad.”

Performance differed between events, which the team tracked as part of the analysis. Runners averaged 6.1 km/h in the MCC and 4.4 km/h in the UTMB, with a reported p-value of 0.009.

Plasma chemistry also split by race length. The MCC was marked by increases in acylcarnitines and fatty acids, which the authors interpret as consistent with greater fat use. The UTMB plasma showed decreases in several lipid groups and higher levels of hypoxanthine, creatine kinase (KCRM), and acute-phase proteins including CRP and SAA1/2, a pattern the authors link to metabolic stress and tissue damage.

One striking theme in the paper is repair work, not just injury.

Red blood cell membranes take damage from oxidation, and the study highlights a shared response after both races: changes consistent with activation of the Lands cycle, a membrane repair process that replaces damaged fatty acid chains. In both races, acylcarnitines rose and lysophospholipids fell, which the authors tie to that repair pathway.

Pantothenate, a precursor needed for CoA, decreased in both races. Carnitine rose only after the UTMB, which the authors suggest may reflect heavy use of the acyl-CoA pool during the longer event.

Oxidized lipid species also increased, including hydroxy- and hydroperoxy-derivatives of linoleate and linolenate. The study reports these rose especially after the MCC.

Inside red blood cells, the metabolite story also diverged by race. The UTMB samples included hydroxylated acylcarnitines, the oxidized linoleate derivative 13(S)-HODE, and kynurenine. They also showed increases in biliverdin and bilirubin after the UTMB but not the MCC.

The authors note that red blood cells are devoid of heme oxygenase, so they interpret those signals as consistent with oxidation-driven heme breakdown, while also acknowledging their high-throughput method does not resolve biliverdin isomers.

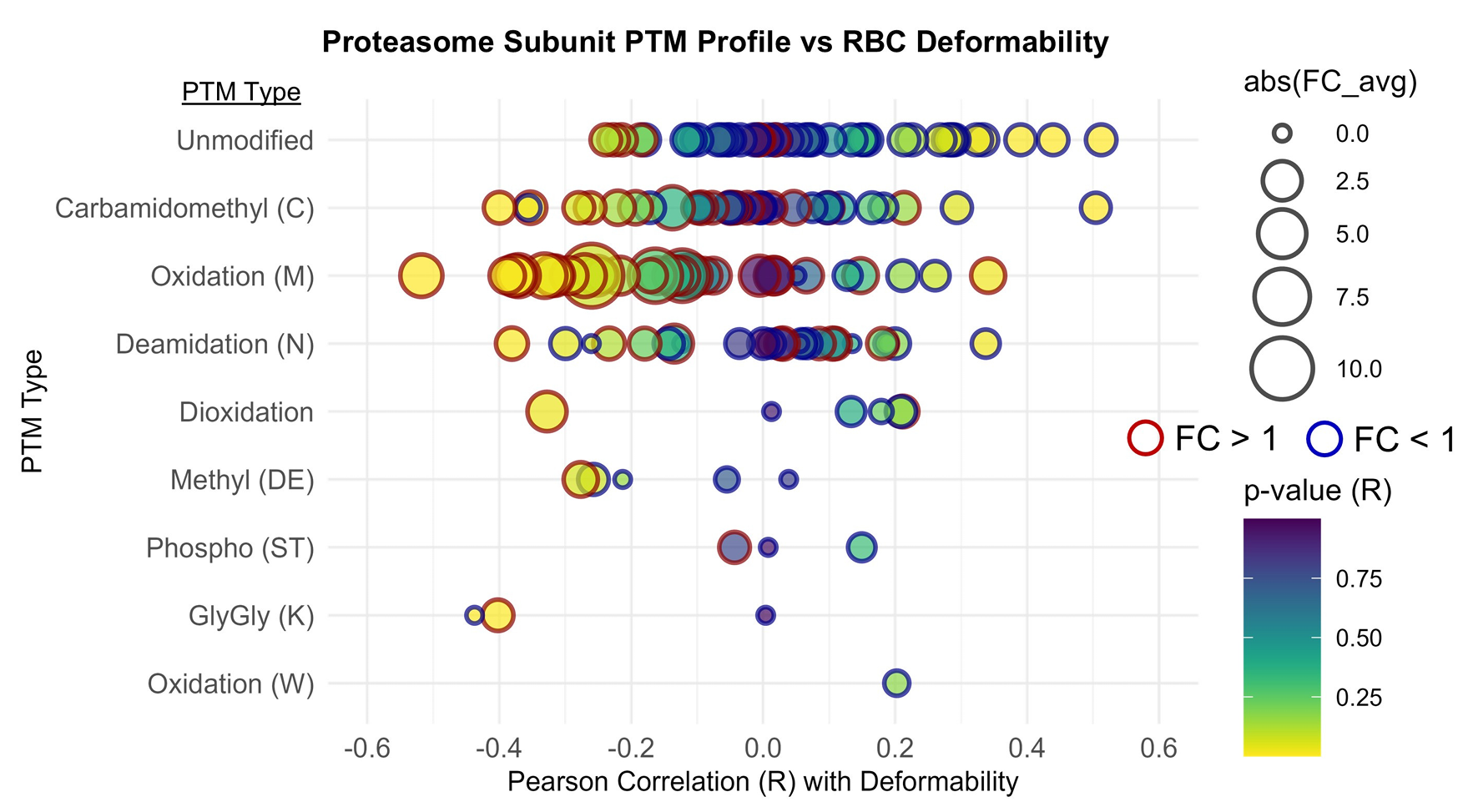

The study connects chemistry to function using deformability tests. Red blood cell deformability declined significantly after the UTMB but not after the MCC.

Proteomics offered one possible reason. Oxidative modifications increased after both races, and oxidation was more pronounced after the UTMB when normalized to total peptide signal. The study highlights methionine oxidation, which rose after both races, and notes that it tracked with reduced deformability and an oxidized glutathione ratio.

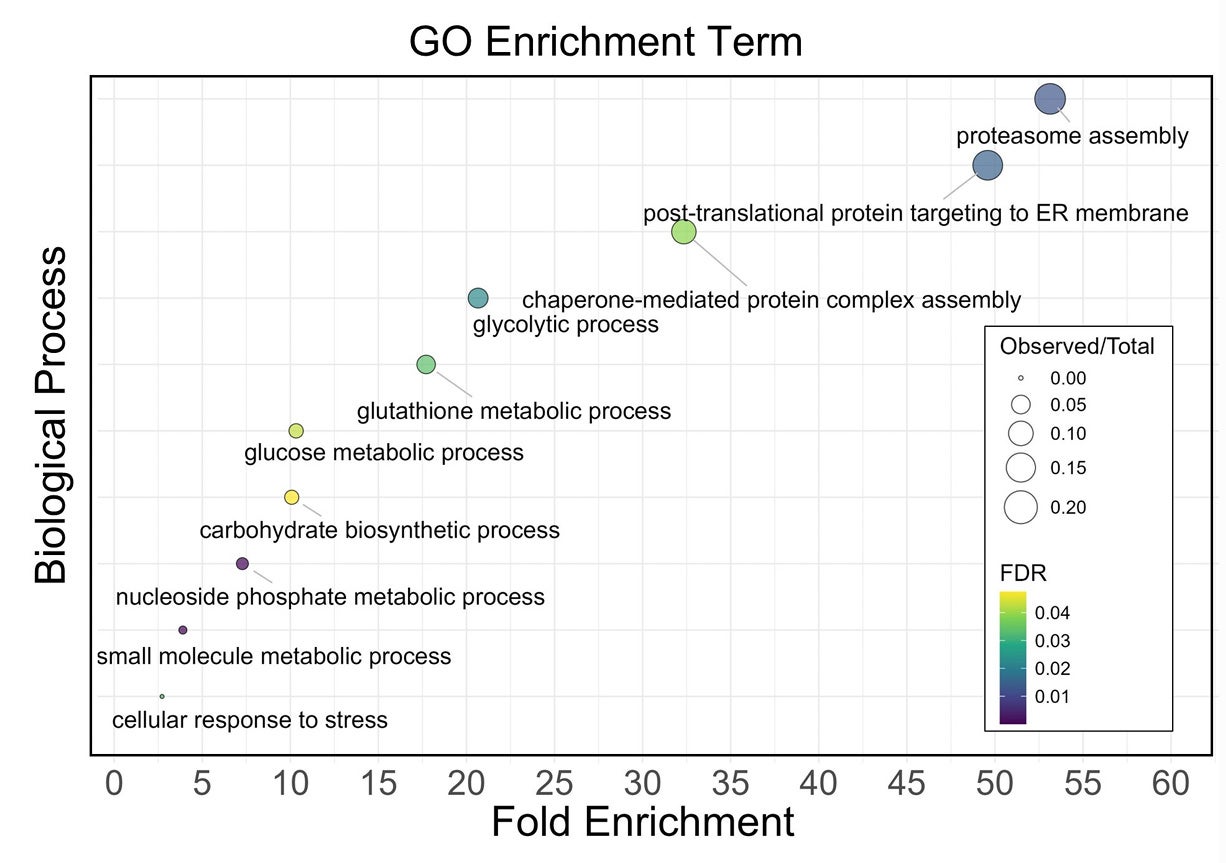

The researchers report that oxidation targeted proteins tied to antioxidant defense, metabolism, the proteasome system, and the cell’s structural scaffold, including spectrin, ankyrin, and band 3. They also report enrichment of proteins shared with neurodegenerative pathways, including Parkinson, Huntington, and Alzheimer pathways, which they present as an example of converging stress on protein maintenance systems.

Metals added another layer. Copper levels rose after the UTMB and correlated inversely with deformability across shear stresses. The authors note copper accumulation is a known feature of the acute-phase response, and that free copper can catalyze lipid peroxidation and impair membrane fluidity in red blood cells.

“Red blood cells are remarkably resilient, but they are also exquisitely sensitive to mechanical and oxidative stress,” said study co-author Angelo D’Alessandro, PhD, professor at the University of Colorado Anschutz and member of the Hall of Fame of the Association for the Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies. “This study shows that extreme endurance exercise pushes red blood cells toward accelerated aging through mechanisms that mirror what we observe during blood storage. Understanding these shared pathways gives us a unique opportunity to learn how to better protect blood cell function both in athletes and in transfusion medicine.”

Classic explanations for runner’s anemia have often leaned on “foot-strike hemolysis,” where repeated impact contributes to red cell breakdown. The authors argue that their data point to more than trauma alone, with oxidative and inflammatory forces shaping damage to membranes, structural proteins, and metabolic pathways.

The paper also leans toward extravascular clearance, meaning the body removes damaged cells through organs like the spleen and liver, rather than widespread bursting of cells in the bloodstream. In support of that, the study links changes such as bilirubin and hypoxanthine patterns to reduced hematocrit after the UTMB, and notes haptoglobin decreased after both races.

The authors also flag an unresolved debate about how much of the post-race drop in hematocrit comes from plasma volume expansion during ultrarunning, versus actual red cell loss. Their data add support for increased removal of damaged cells, but they do not claim a single cause.

The study has clear limits. It involved only 23 participants, lacked racial diversity, and sampled blood at only two time points, immediately before and after races. The authors say they are planning studies with more participants, more sampling, and additional post-race measurements.

Research findings are available online in the journal Blood Red Cells & Iron.

The original story “Researchers link ultra-endurance running to accelerated red blood cell aging” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Researchers link ultra-endurance running to accelerated red blood cell aging appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.