Obesity now affects nearly half of adults worldwide. Global estimates show about 43 percent of adults are overweight, and 16 percent live with obesity. These numbers matter because excess weight sharply raises the risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and several cancers. For years, fat tissue was seen as passive storage. Research now shows it acts as a dynamic organ that shapes metabolism across the body.

Inside this tissue, a process called adipogenesis turns immature precursor cells into fat-storing adipocytes. When this process becomes overactive, fat tissue expands and metabolic disease follows. Understanding what controls this shift remains one of the central challenges in obesity research.

A new study led by Professor Hyun Kook at Chonnam National University Medical School in the Republic of Korea sheds light on one of those controls. The work identifies Ret finger protein, or RFP, also known as TRIM27, as a key driver of fat cell formation and metabolic dysfunction. The findings were published in Experimental & Molecular Medicine, Volume 57.

“We discovered that RFP behaves like a hidden accelerator for obesity,” Kook said. “When RFP levels are high, fat cells form and expand much more easily, and when RFP is absent, the body resists weight gain, even under a high-fat diet.”

RFP was not new to this research team. Earlier studies showed it acts as a brake on muscle formation. It suppresses myogenesis by blocking muscle-related genes and promoting the breakdown of MyoD, a master muscle regulator. During muscle injury experiments in mice lacking RFP, researchers noticed lipid-filled spaces in muscle tissue. That unexpected detail raised a new question. Could RFP help decide whether precursor cells become muscle or fat?

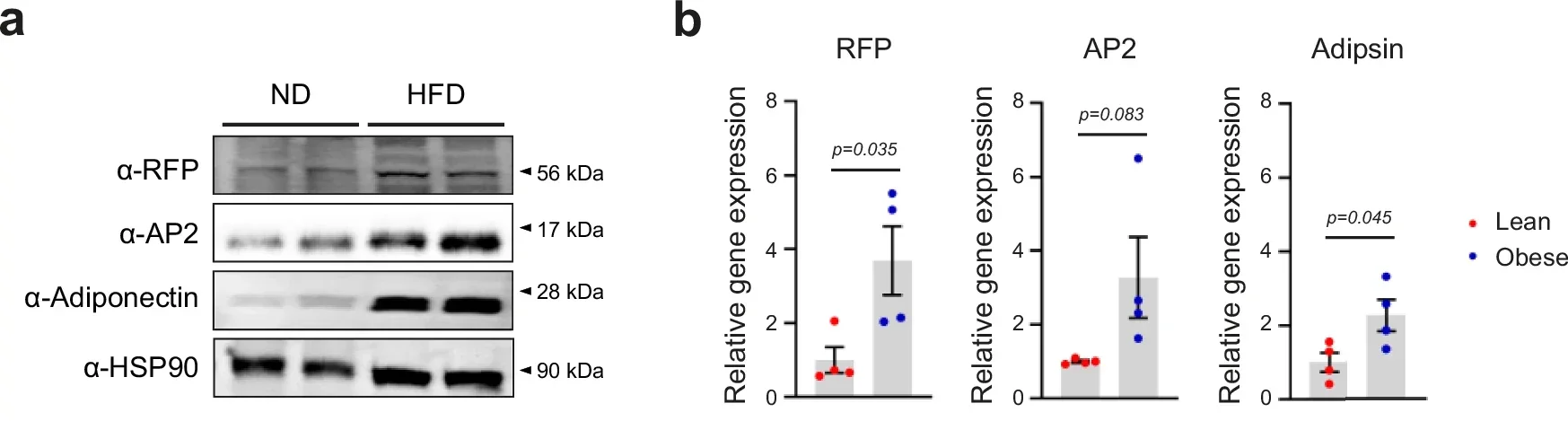

To explore this idea, the team first examined whether RFP levels change with obesity. Wild-type mice were fed either a standard diet or a diet where 60 percent of calories came from fat. In visceral fat tissue, the high-fat diet boosted classic fat cell markers like AP2 and adiponectin. RFP levels rose alongside them.

Human data told a similar story. Fat samples taken from the abdomen of obese individuals showed higher levels of RFP and adipogenic markers than samples from lean individuals. Imaging revealed RFP clustered in cell nuclei, with stronger signals in obese tissue. These findings suggested RFP responds directly to an overfed state.

The researchers then asked what happens when RFP is removed. Male mice lacking RFP and their normal littermates were fed either a regular or high-fat diet for up to 12 weeks. Body weight and food intake were carefully tracked.

On the high-fat diet, normal mice gained significant weight and fat mass. Mice without RFP remained largely protected. They accumulated far less visceral and subcutaneous fat, despite eating similar amounts of food. Brown fat, which plays a role in heat production, showed little difference between groups.

Microscopic analysis offered a clear explanation. In normal mice, fat cells grew large and swollen under the high-fat diet. In mice lacking RFP, fat cells stayed smaller. Gene analysis showed that many fat-building genes rose sharply in normal mice but remained muted when RFP was absent.

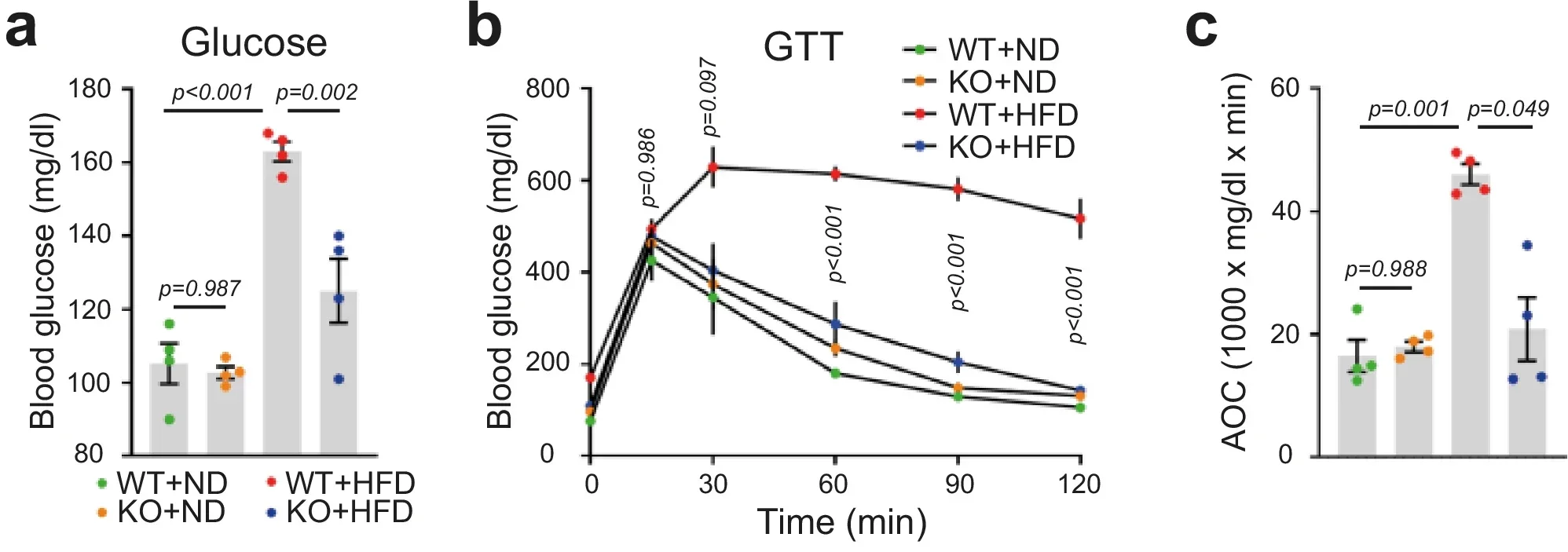

Excess fat often disrupts glucose control. To test this, the team ran glucose and insulin tolerance tests. Normal mice on a high-fat diet showed prolonged spikes in blood sugar and high insulin levels, signs of insulin resistance. Mice lacking RFP cleared glucose more efficiently and maintained healthier insulin levels.

Blood markers linked to obesity also improved. Levels of leptin, free fatty acids, and triglycerides were lower in mice without RFP. When placed in metabolic cages, these mice burned more energy at rest. Food intake and physical activity did not differ much, suggesting a metabolic shift rather than behavioral changes.

Because metabolism involves many organs, the researchers created mice lacking RFP only in fat cells. These adipocyte-specific knockout animals showed the same protection against weight gain and metabolic decline as mice lacking RFP throughout the body.

They gained less weight on a high-fat diet, stored less fat, and maintained smaller adipocytes. Blood sugar and lipid profiles improved, and energy expenditure increased. These results pointed to fat tissue itself as the main site where RFP drives metabolic changes.

One open question remained. Does RFP affect fat breakdown, known as lipolysis? Lower circulating fatty acids in RFP-deficient mice could reflect either reduced fat release or simply less fat overall.

To sort this out, the team used fasting and refeeding experiments and tested isolated fat cells with drugs that trigger fat breakdown. In each case, fat release looked similar regardless of RFP status. These findings showed RFP does not control fat burning. Instead, it promotes fat building.

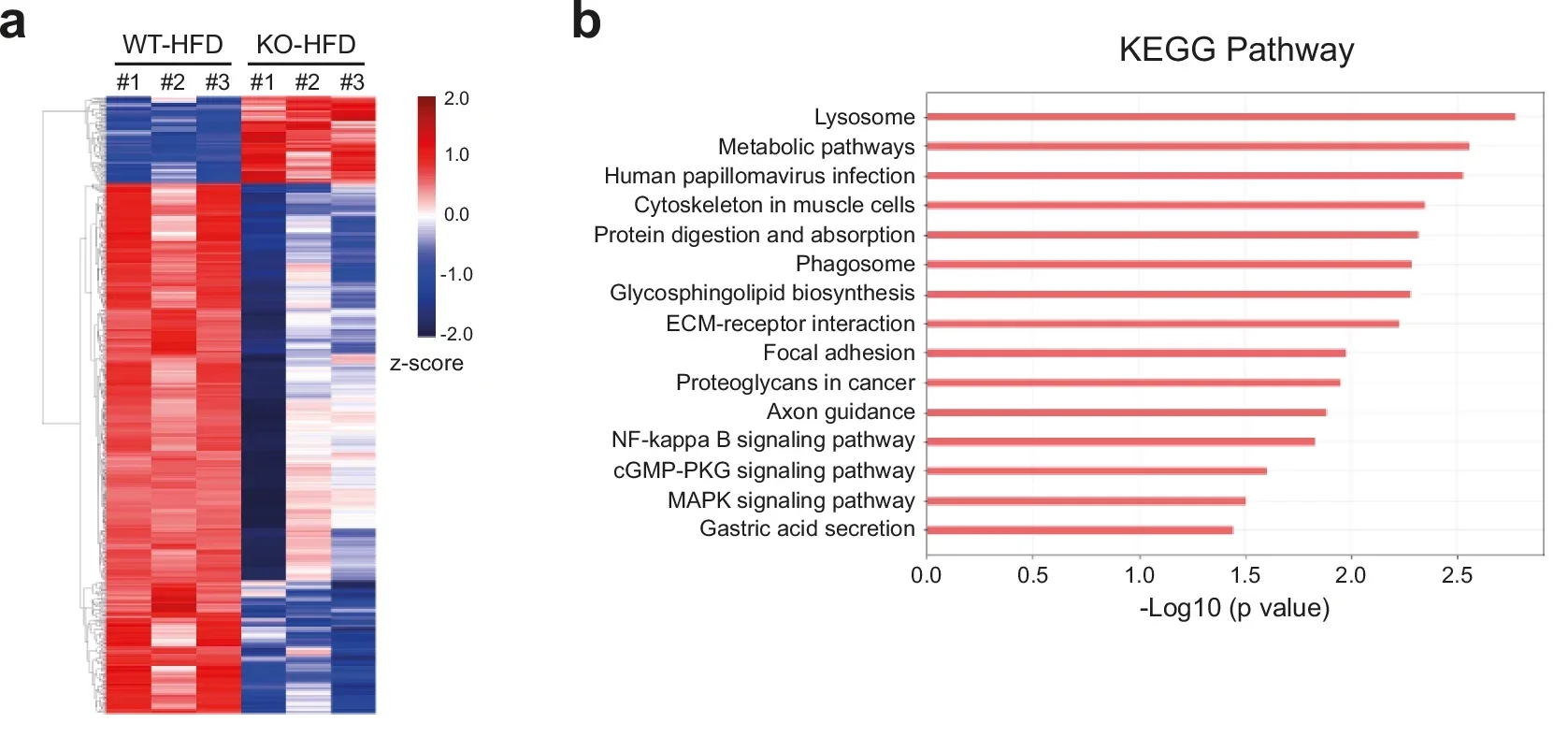

At the molecular level, RFP exerts its influence by partnering with PPAR-γ, the master regulator of fat cell formation. Gene sequencing revealed that fat tissue from RFP-deficient mice showed broad suppression of adipogenesis and obesity-related gene programs.

“Cell experiments confirmed the mechanism. We found that sharply reducing RFP levels limited lipid accumulation, while increasing RFP enhanced it. Further tests showed RFP binds directly to PPAR-γ in the cell nucleus, strengthening its ability to activate fat-building genes like AP2 and adiponectin.” Kook shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“The mechanism connects everything,” he continued. “RFP strengthens PPAR-γ signaling, pushing fat cell formation forward. Without RFP, fat cell formation is suppressed and the metabolic profile improves.”

These findings deepen understanding of how fat tissue expands and why obesity develops. By identifying RFP as a molecular driver of adipogenesis, the study highlights a potential new point of intervention.

Future therapies might aim to temper fat cell formation rather than only suppress appetite or boost calorie burning.

While RFP itself may not become a direct drug target, mapping its interaction with PPAR-γ could guide safer strategies to prevent obesity and its complications before they take hold.

Research findings are available online in the journal Experimental & Molecular Medicine, Volume 57.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Ret finger protein behaves like a hidden accelerator for obesity, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.