In medieval Denmark, death could double as a display of status. The closer your grave lay to a church wall or inside a monastery, the more it likely cost. Wealth followed you into the ground.

That raised a harder question. If someone carried a disease tied to stigma, would that person still rest near the altar?

A team led by Dr. Saige Kelmelis of the University of South Dakota set out to test that idea. Working with Vicki Kristensen and Dr. Dorthe Pedersen of the University of Southern Denmark, Kelmelis examined nearly a thousand skeletons from medieval cemeteries. Their findings appear in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology.

“When we started this work, I was immediately reminded of the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, specifically the scene with the plague cart,” Kelmelis said. “I think this image depicts our ideas of how people in the past — and in some cases today — respond to debilitating diseases. However, our study reveals that medieval communities were variable in their responses and in their makeup. For several communities, those who were sick were buried alongside their neighbors and given the same treatment as anyone else.”

That image of townspeople crying “bring out your dead” has shaped modern assumptions. The medieval world often gets painted as fearful, dirty, and quick to cast out the ill. The bones from Denmark tell a more complicated story.

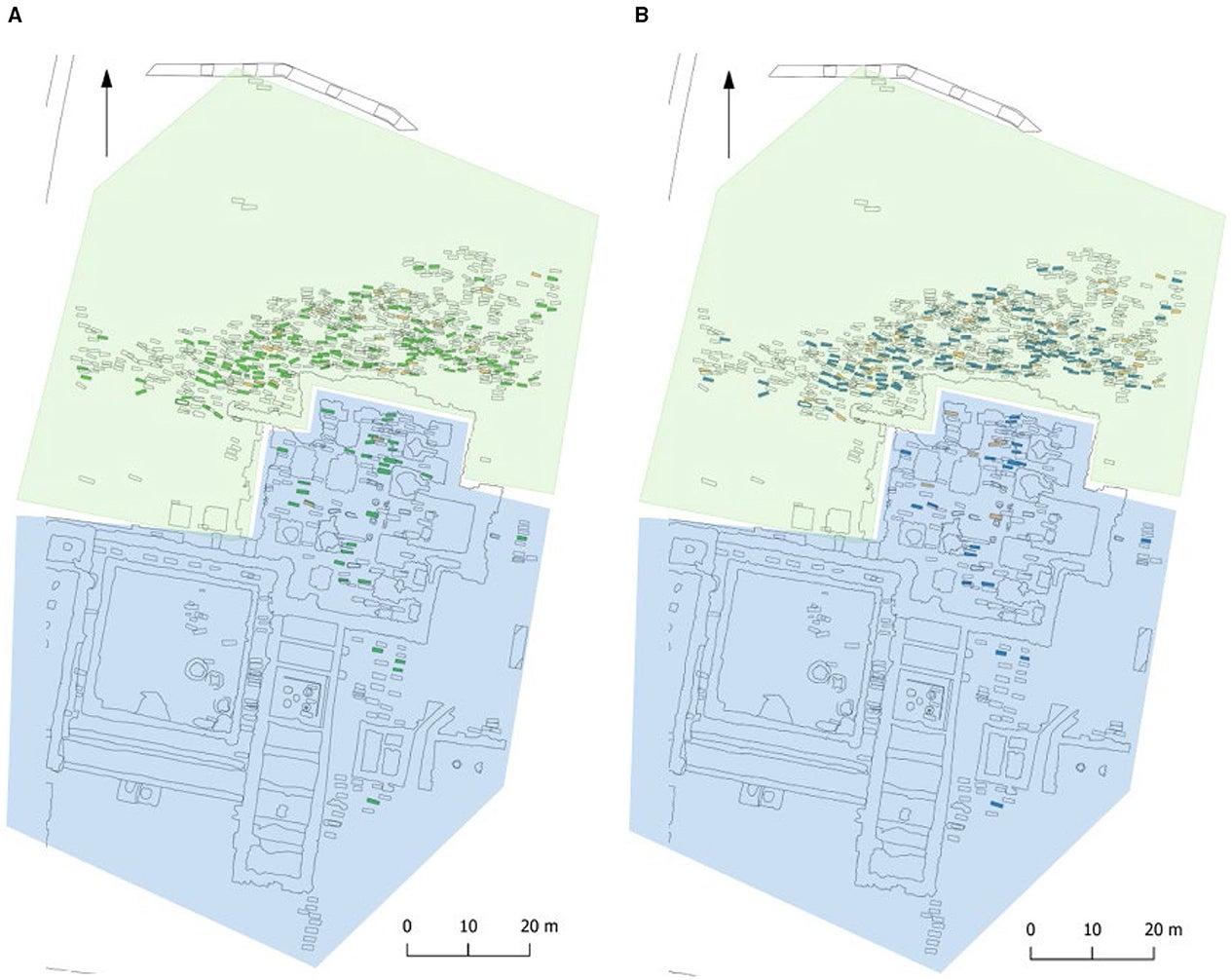

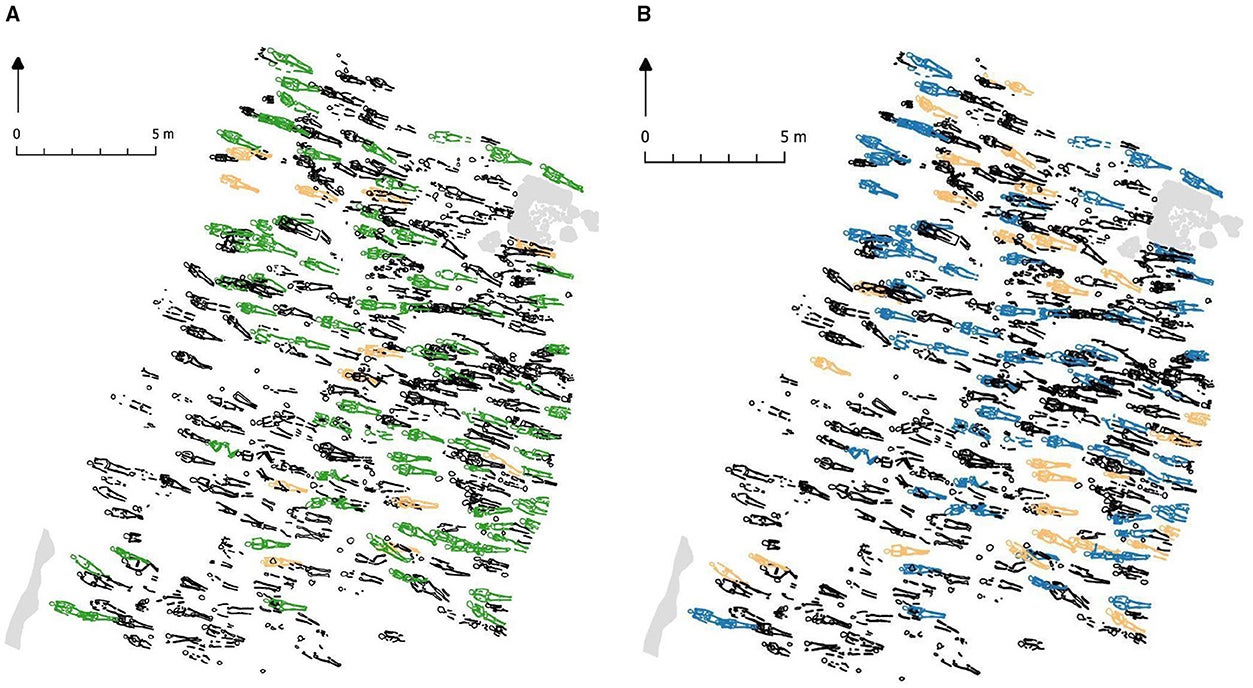

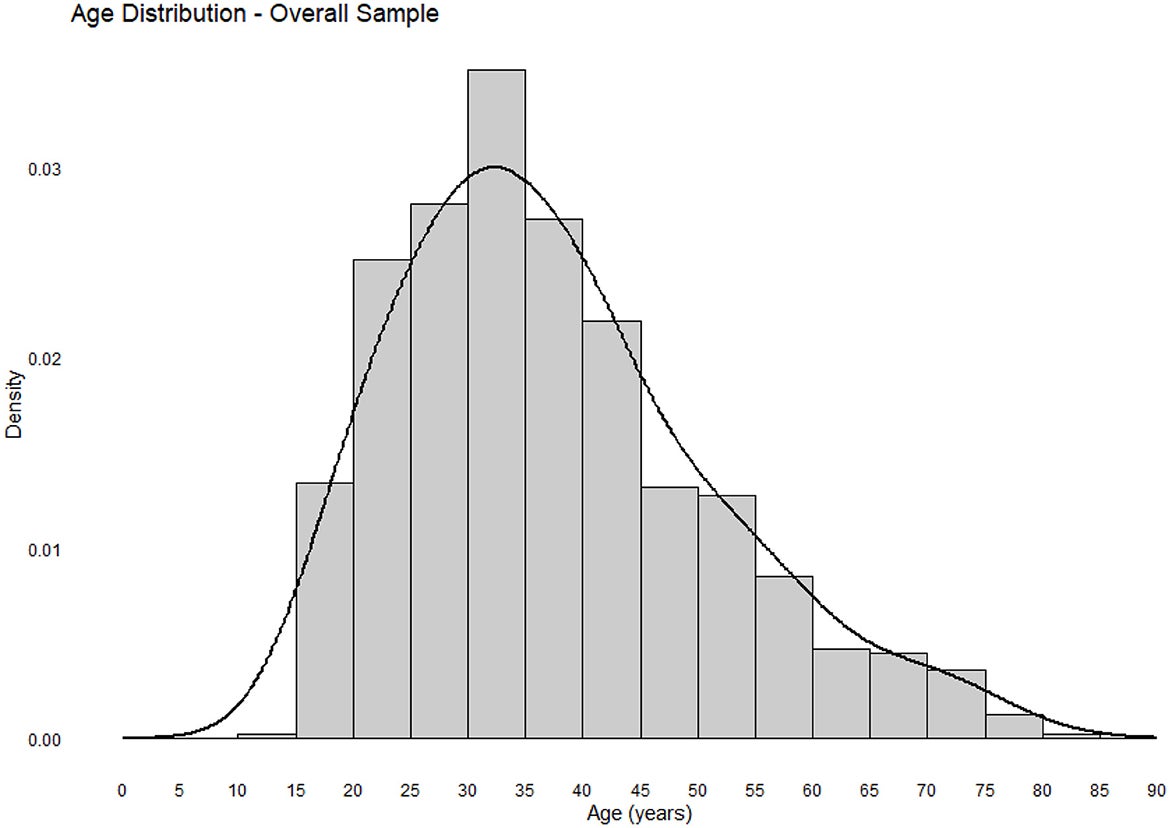

The researchers studied 939 adult skeletons from five cemeteries dating from about 1050 to 1536. Three sites were urban: Ribe Grey Friars, Drotten in Viborg, and St. Mathias, also in Viborg. Two were rural: Sejet and the Cistercian monastery Øm Kloster.

They searched for skeletal signs of leprosy and tuberculosis. Leprosy can damage the face, hands, and feet. Tuberculosis often leaves marks on ribs, vertebrae, and joints near the lungs.

Leprosy carried visible signs. Facial lesions could mark someone as different. Tuberculosis often did not.

“Tuberculosis is one of those chronic infections that people can live with for a very long time without symptoms,” Kelmelis said. “Also, tuberculosis is not as visibly disabling as leprosy, and in a time when the cause of infection and route of transmission were unknown, tuberculosis patients were likely not met with the same stigmatization as the more obvious leprosy patients. Perhaps medieval folks were so busy dealing with one disease that the other was just the cherry on top of the disease sundae.”

Each skeleton received a disease score based on established criteria. The team then mapped every burial. Graves near church buildings or inside monastery complexes counted as higher status. Those farther away counted as lower status.

If stigma shaped burial, a pattern should have appeared on those maps.

It did not.

Across the full sample, there was no overall link between disease and burial location. People with leprosy or tuberculosis appeared in both high- and low-status areas.

Leprosy rates differed by location. The urban parish cemeteries in Viborg had low leprosy frequencies, 3.4 percent at Drotten and 4.6 percent at St. Mathias. Rural Sejet reached 13 percent. Øm Kloster stood at 11.9 percent. Ribe Grey Friars fell in between at 8.9 percent.

That likely reflects the presence of leprosaria in towns such as Viborg and Ribe. Urban sufferers with severe facial symptoms may have been buried in those institutions instead of parish cemeteries.

Tuberculosis told another story. It was far more common. At Drotten, 51.6 percent of individuals showed skeletal signs. Other sites ranged between 21.8 percent and 32 percent.

At Ribe Grey Friars, 32.6 percent of those in the lower-status northern cemetery had tuberculosis, compared with 12 percent in the higher-status church and monastery complex. That was the only clear link between disease and burial area.

When the team pooled all cemeteries, social status did not significantly predict who had leprosy or tuberculosis.

They also examined survival patterns using statistical models. Urban residents overall faced higher mortality risk than rural residents. Yet variation between individual cemeteries was striking. Drotten, an urban site, showed lower mortality risk than several other locations.

Leprosy did not significantly affect survival. Tuberculosis produced a surprising pattern: individuals with skeletal signs of TB showed higher survivorship than those without lesions.

That does not mean tuberculosis was mild. Bone lesions form only if someone survives long enough for the disease to leave marks. Those who died quickly from TB would not show skeletal damage. The paradox has long been known in bioarchaeology.

“Individuals may have been carrying the bacteria but died before it could show up in the skeleton,” Kelmelis cautioned. “Unless we can include genomic methods, we may not know the full extent of how these diseases affected past communities.”

The broader picture challenges a simple narrative of exclusion. Medieval Denmark saw the rise of more than 40 leprosaria by the time of the Protestant Reformation in 1536. These institutions likely filtered some urban burials. But parish cemeteries still included people with visible disease.

The researchers found no strong evidence that visibly ill individuals were pushed to cemetery margins in most of the sites examined. Burial location followed social rank more than disease status.

Monastic rules at Øm Kloster required simple graves for the sick, with cleansing and prayer before burial. Christian custom emphasized east–west alignment and modest interment. Those patterns held whether someone bore lesions or not.

The image of medieval society as uniformly cruel toward the sick does not fit these data. In many communities, neighbors lay side by side in death, regardless of infection.

The ticket to a grave near the altar seems to have depended less on illness and more on wealth.

This study reshapes how medieval health crises are understood. It suggests that stigma did not automatically dictate burial treatment. Social class and access to religious institutions mattered more than visible disease.

For historians and archaeologists, the findings warn against reading exclusion into every case of illness. Disease patterns must be viewed alongside economic and religious structures.

For a modern audience, the work offers perspective. Societies under stress do not always respond in predictable ways. Even in periods marked by epidemics, communities could balance fear with charity and shared ritual.

Research findings are available online in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology.

The original story “Rich medieval Danes bought graves ‘closer to God’, study finds” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Rich medieval Danes bought graves ‘closer to God’, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.