Astronomers have chased hypervelocity stars for more than a century. These rare objects move so fast that the Milky Way cannot keep them. When a star exceeds the galaxy’s escape speed, it becomes “unbound” and heads outward.

Now a team in Beijing, led by Haozhu Fu of Peking University, has widened that search. The group drew on large star catalogs and new sky measurements. Their results appear in The Astrophysical Journal. They focused on an unusual target; RR Lyrae stars.

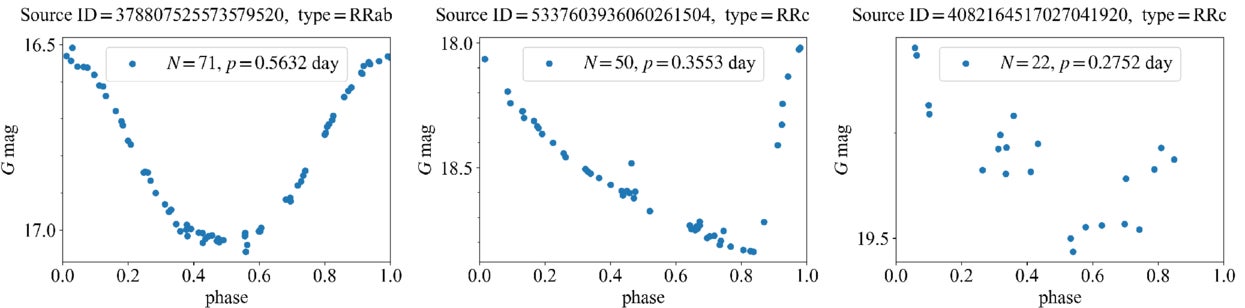

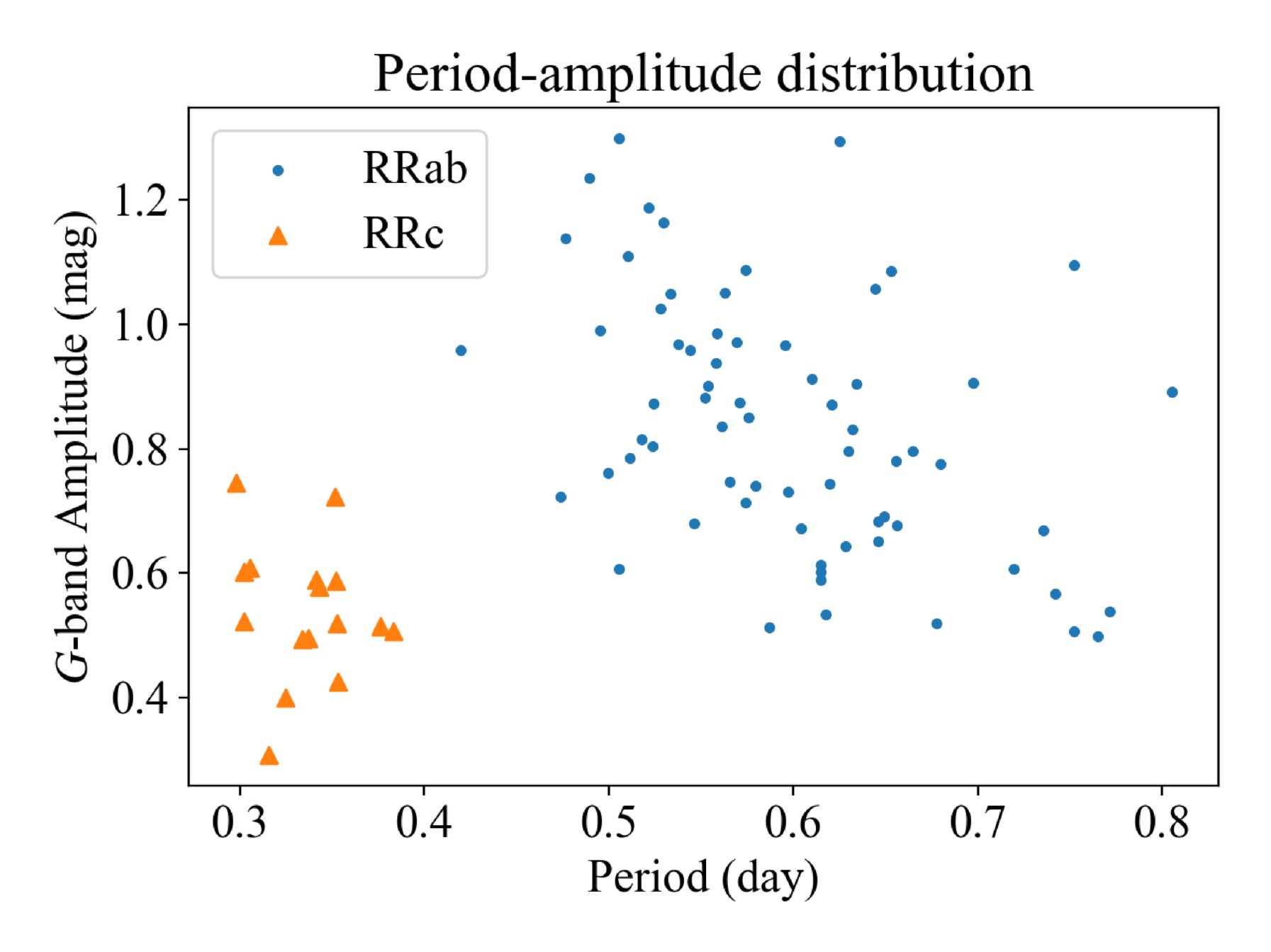

RR Lyrae stars pulse in brightness with steady, predictable rhythms. That regular beat lets you estimate how far away they are. Those distance estimates matter because speed depends on distance. Get the distance wrong, and a normal star can look like a galactic sprinter.

To track motion, the researchers relied on the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite. Gaia measures tiny shifts in a star’s position over time. Those shifts reveal proper motion, meaning motion across the sky. When you combine proper motion with distance, you can estimate tangential speed.

Escape velocity is the speed needed to break free from gravity. Earth’s escape speed is 11.2 kilometers per second. The sun’s escape speed is about 618 kilometers per second at its surface. From Earth’s orbit, it is far lower.

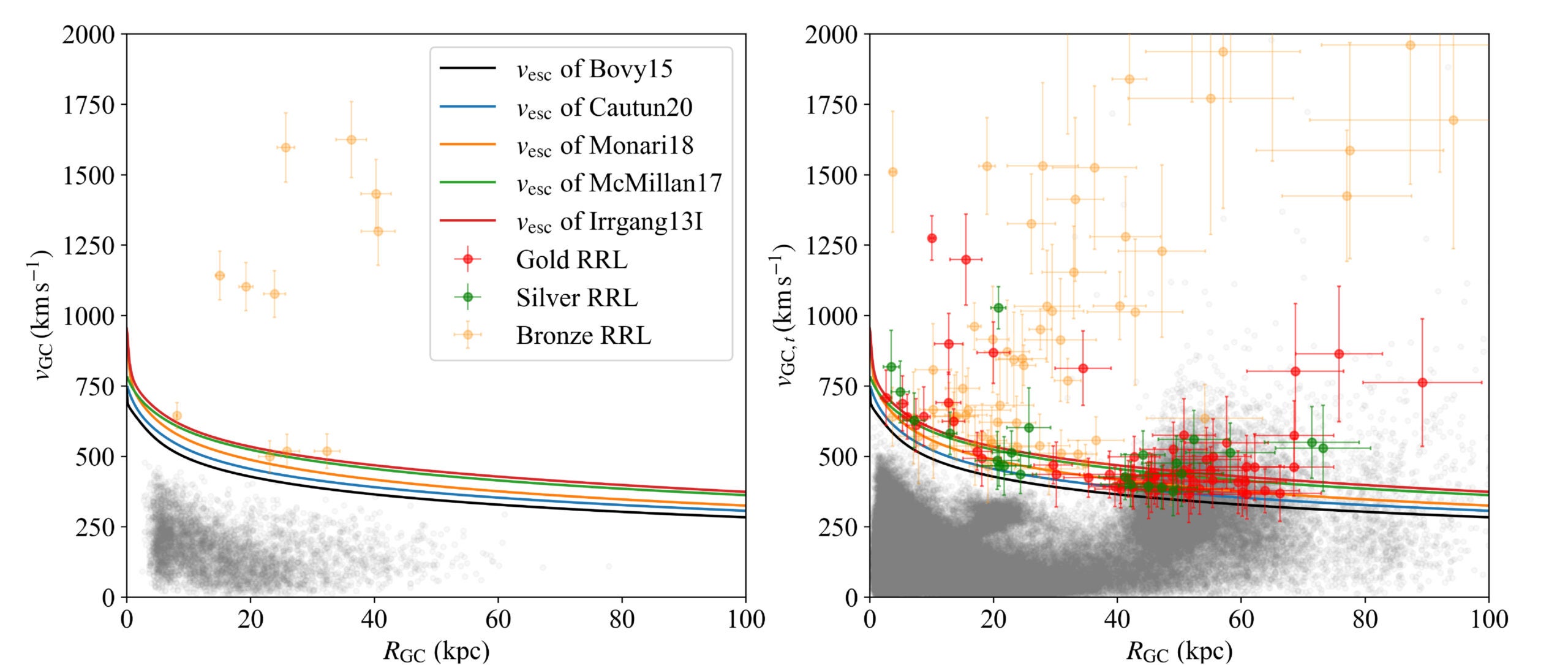

For the Milky Way, escape speed near the sun is often described as roughly 550 kilometers per second. Hypervelocity stars can reach about 1,000 kilometers per second or more. At those speeds, the galaxy’s pull is not enough.

One classic explanation involves the Milky Way’s central black hole, Sagittarius A*. In 1988, astronomer Jack Hills proposed a process now called the Hills mechanism. A binary star pair drifts too close to the black hole. Gravity tears the pair apart. One star gets captured, and the other is launched outward.

These runaway stars are not just oddities. If you trace their paths backward, you can test the Milky Way’s gravitational potential. That can also help you study the galaxy’s dark matter halo. But first, you must find strong candidates.

Fu and his colleagues began with two major RR Lyrae catalogs. One held 8,172 RR Lyrae stars from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Another contained 135,873 RR Lyrae stars with metallicity and distance estimates from Gaia photometry.

RR Lyrae stars help because their intrinsic brightness is constrained. Their pulse period, absolute magnitude, and metallicity link together. If you know how bright the star truly is, and how bright it looks from Earth, you can estimate distance.

“Our team merged catalogs and removed duplicates. They then cross-matched the stars with Gaia’s third data release, often called DR3. Gaia’s strength is astrometry, not spectroscopy. That matters because faint, distant stars often lack good radial velocity data,” Fu explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“Instead of requiring a full 3D speed, our study often used tangential speed alone. The logic is direct. If tangential speed exceeds escape speed, the total speed must be even higher. That star becomes a hypervelocity candidate,” he continued.

Distance errors still pose a risk. Small proper-motion mistakes can inflate speed at large distances. So the researchers applied strict Gaia quality filters. After that screening, they kept 110,823 RR Lyrae stars for analysis.

To handle uncertainty, the team ran 2,000 Monte Carlo simulations per star. They treated key measurements as distributions, not fixed values. From those simulations, they calculated an “unbound probability,” called Punb. That value reflects how often a star’s simulated speed beats escape speed.

This step produced 8,090 RR Lyrae stars with Punb above 0.5. The team then removed stars with large relative velocity uncertainties. That left 6,838.

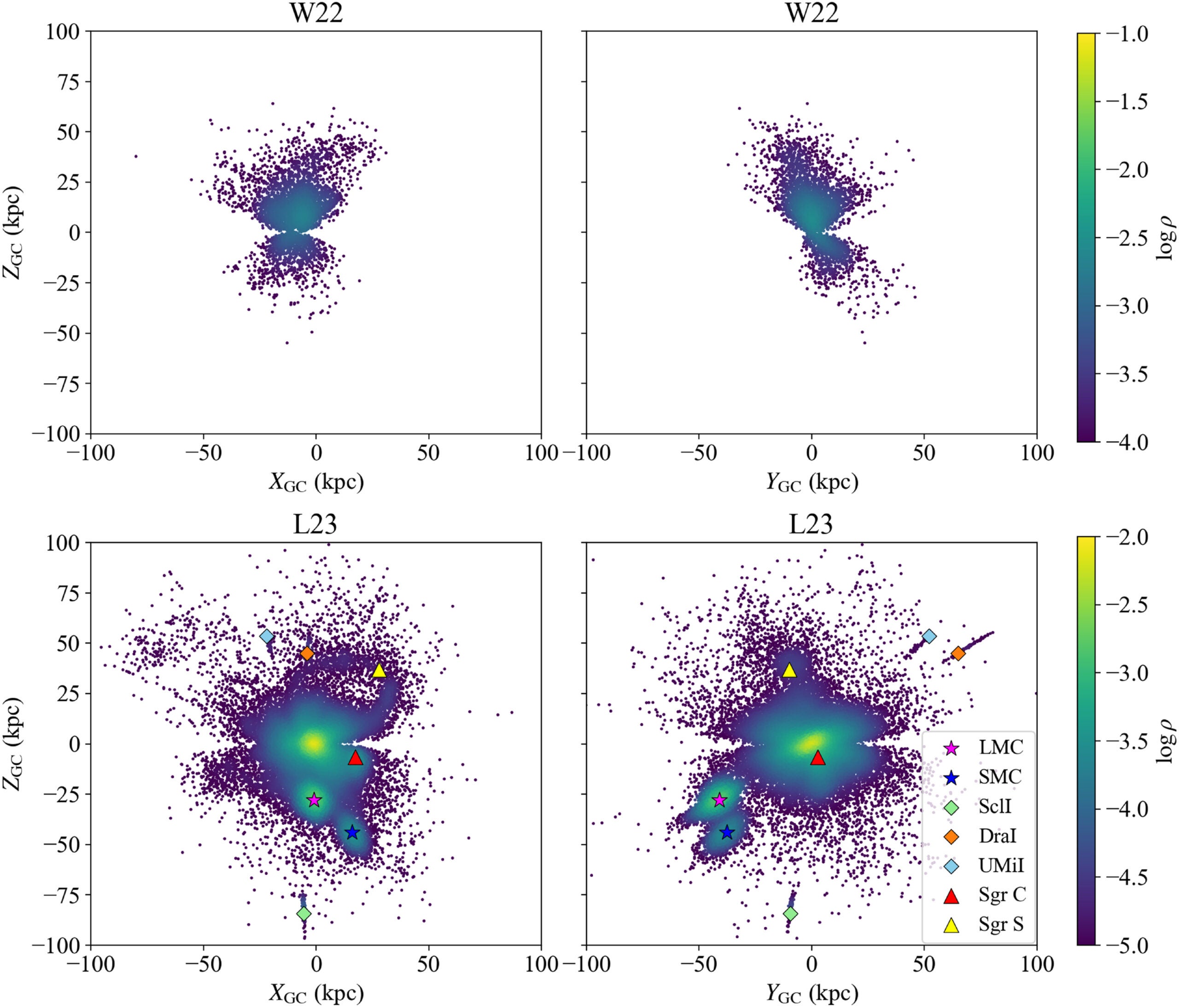

Most of those were not treated as isolated escapees. Many sit in known structures, like dwarf galaxies and star clusters. The researchers checked for associations with globular clusters, dwarf galaxies, the Magellanic Clouds, and the Sagittarius system.

That filtering removed 97.6% of the unbound set. It left 165 “unbound field stars” that were not tied to known substructures. Those became the study’s final list of hypervelocity RR Lyrae candidates.

Then came a reality check. RR Lyrae distances depend on correct classification and clean light curves. So the team inspected light curves using Gaia DR3 and other survey data. They sorted candidates into “gold sample,” “silver sample,” and “bronze sample.”

The “gold sample” looked like clear RR Lyrae behavior. The “silver sample” looked plausible but noisier. The “bronze sample” raised doubts about classification, which can distort distance and speed.

Among the more reliable gold and silver stars, several stood out. Seven had tangential speeds above 800 kilometers per second. Three exceeded 1,000 kilometers per second.

Their positions on the sky revealed two clear groupings. One group lies near the Milky Way’s center, consistent with ejection by the central black hole. Another cluster appears near the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, two nearby dwarf galaxies.

This second group raised questions. The Magellanic Clouds move quickly themselves and have strong gravity. When the researchers accounted for the Large Magellanic Cloud’s pull, many nearby candidates no longer appeared truly unbound from the Milky Way.

That suggests some stars may still be tied to the Magellanic system rather than escaping the galaxy.

Chemical makeup offered another hint. Stars closer to the galactic center tended to have slightly higher metal content. Stars near the Magellanic Clouds and in the outer halo were more metal-poor. The difference was small but noticeable.

Most candidates lack full velocity data. Without radial velocity measurements, astronomers cannot trace exact paths back in time. That limits certainty about where these stars came from.

One exception in the study had a measured radial velocity. After correcting for the star’s pulsation, it still exceeded the local escape speed. Even so, its path did not clearly point back to the galactic center. It may have passed near a globular cluster instead.

The researchers stress that more spectroscopy is needed. Better data can confirm which stars are truly escaping and which only appear fast due to motion within other systems.

Research findings are available online in the journal The Astrophysical Journal.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Runaway stars within the Milky Way may reveal dark matter’s hidden structure appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.