More than 300 years ago, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus began an ambitious effort to identify and name every living organism. His system of binomial names still shapes how you understand life today. That project, however, remains unfinished. New research led by scientists at the University of Arizona shows that the effort to formally describe Earth’s species is not slowing. Instead, it is accelerating.

The study, published in Science Advances, is led by John Wiens, a professor in the university’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. His team examined how fast scientists are formally describing species across nearly all branches of life. Their focus was not on guessing how many species exist overall. Instead, they asked how quickly species move from being unknown to officially recognized by science.

That distinction matters to you. A species does not count in conservation law, databases, or policy until scientists formally describe and name it. Before that step, it is effectively invisible.

“Some scientists have suggested that the pace of new species descriptions has slowed down and that this indicates that we are running out of new species to discover, but our results show the opposite,” Wiens said. “In fact, we’re finding new species at a faster rate than ever before.”

To reach their conclusions, the researchers analyzed taxonomic records for about 2 million living species. They used the Catalogue of Life and related databases, excluding fossils and viruses. Their analysis extended through 2020, the most recent year with reliable global data.

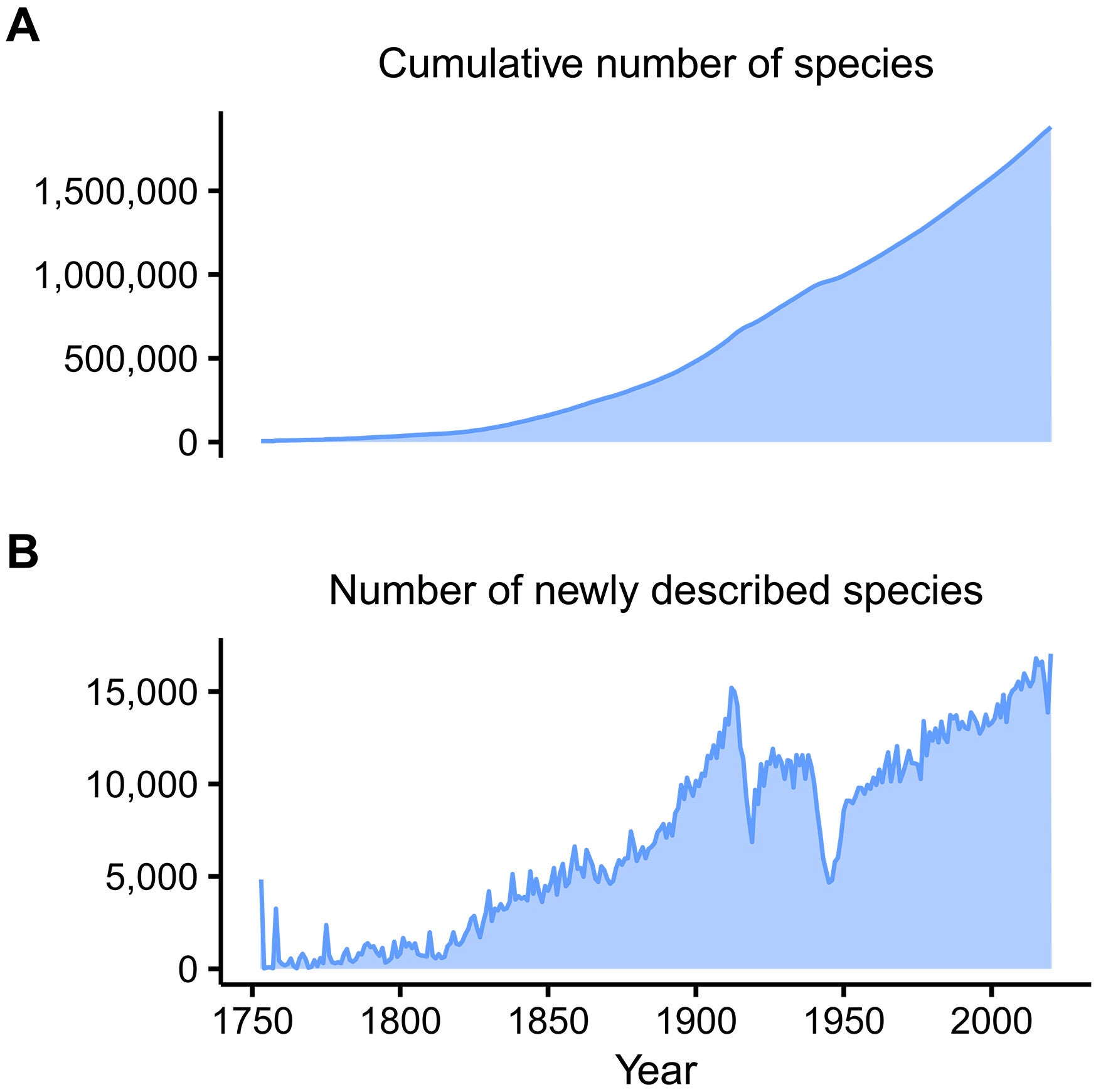

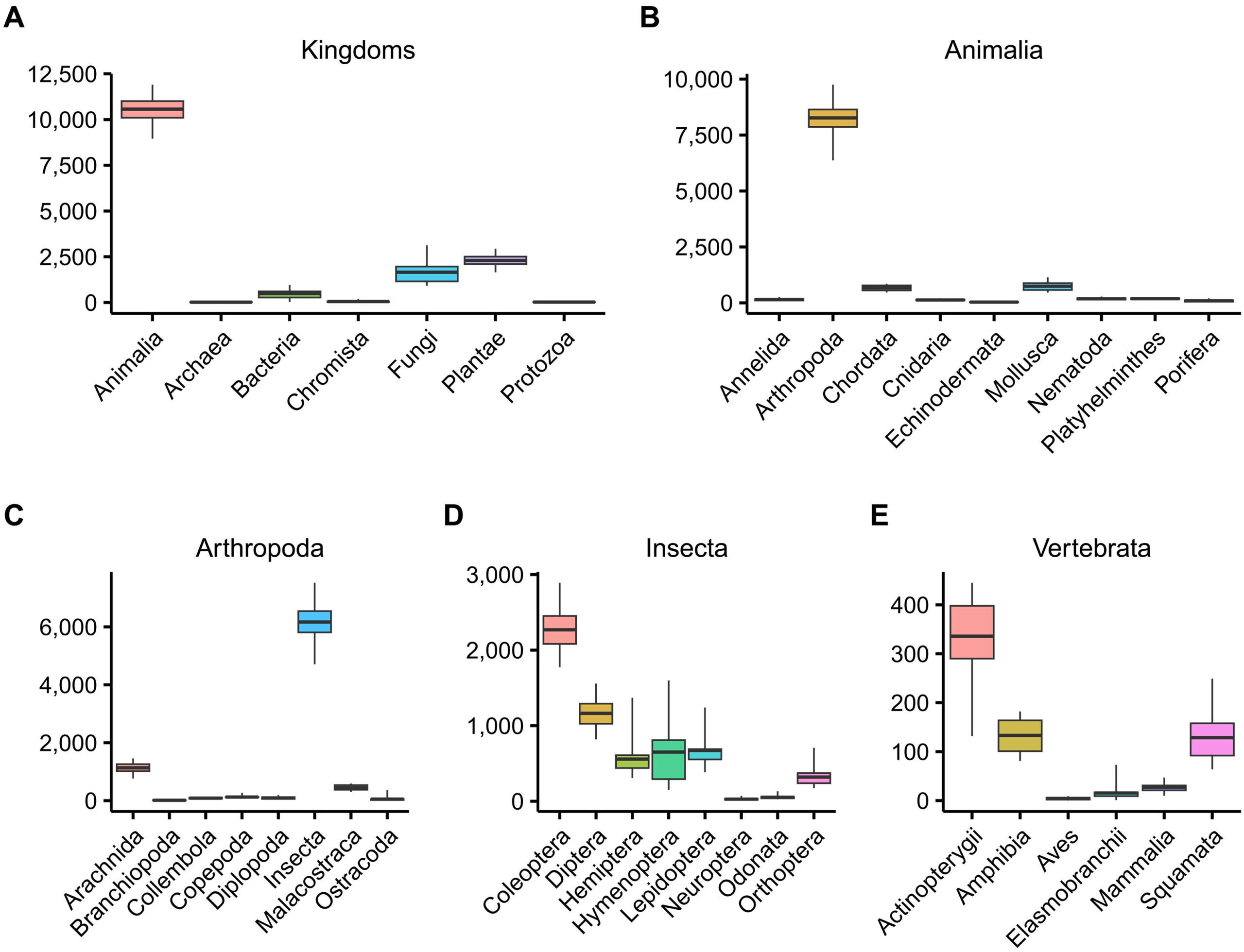

Between 2015 and 2020, scientists formally described more than 16,000 new species each year on average. That includes over 10,000 animals, mainly insects and other arthropods, about 2,500 plants, and roughly 2,000 fungi. The single busiest year on record was 2020, when scientists named 17,044 new species.

These numbers overturn older claims that species discovery peaked around 1900. Earlier studies relied on narrower datasets and did not capture the surge of work in recent decades. According to this analysis, description rates did not surpass early 20th-century highs until after 2008. Since then, they have continued to climb.

“Our good news is that this rate of new species discovery far outpaces the rate of species extinctions, which we calculated to about 10 per year,” Wiens said, referring to another study his team published earlier. “These thousands of newly found species each year are not just microscopic organisms, but include insects, plants, fungi and even hundreds of new vertebrates.”

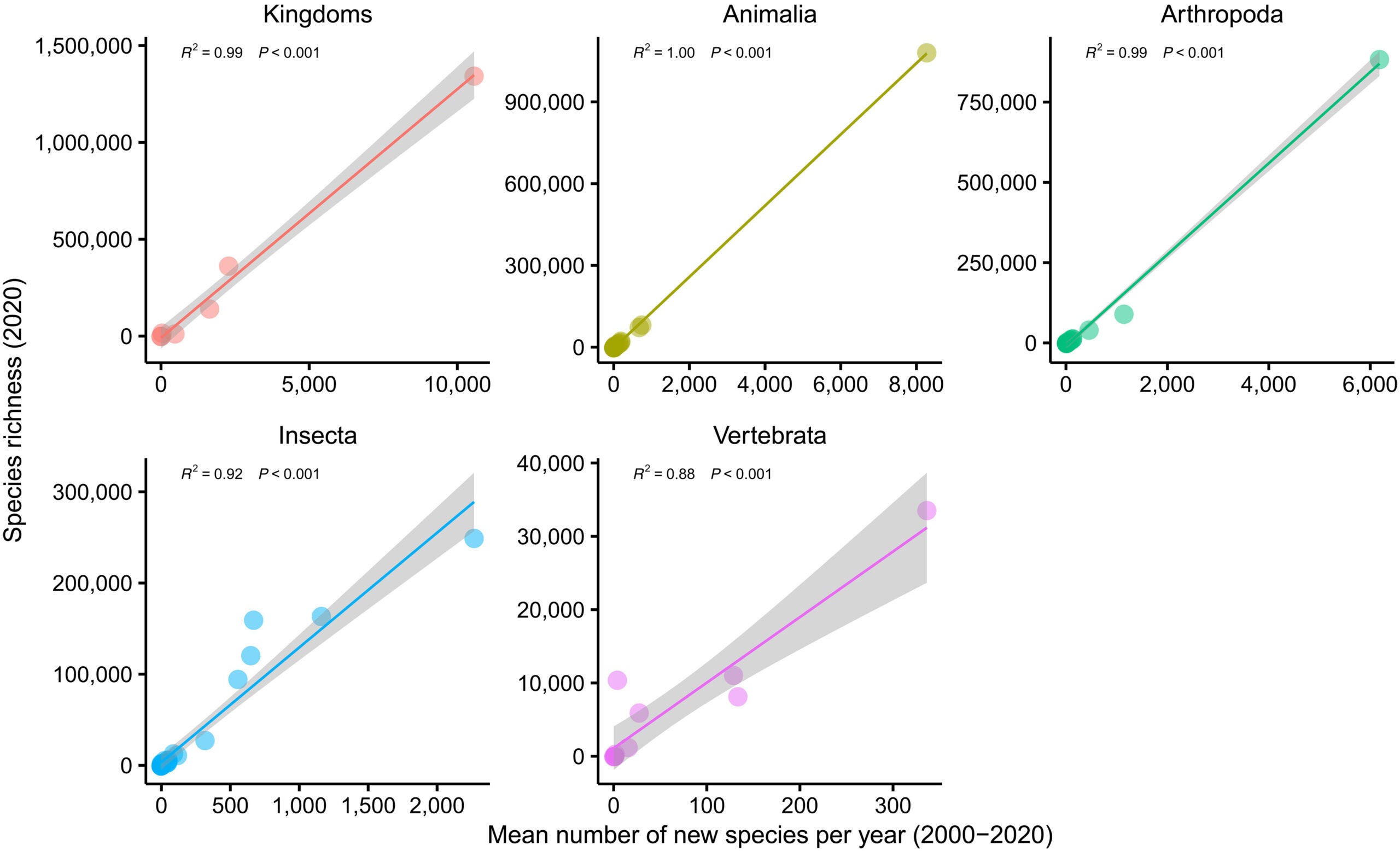

When you look closely, the growth in known species is not evenly spread. Larger groups tend to gain new species faster than smaller ones. Animals lead all kingdoms in annual discovery rates. Within animals, arthropods dominate. Insects grow fastest among arthropods, with beetles standing out even among insects. Among vertebrates, ray-finned fishes top the list.

From 2000 to 2020 alone, animals added species equal to about 17 percent of their total known diversity in 2020. Beetles increased by nearly one-fifth. Ray-finned fishes grew by more than 20 percent. In just two decades, taxonomists expanded many groups by roughly one-sixth or more.

This pattern surprised the researchers. Smaller or neglected groups could have been catching up. Instead, the biggest branches of life continue to pull further ahead, both in total species and in new discoveries each year.

Over longer time scales, species description follows a patchwork shaped by history. Animal discoveries show clear dips during World Wars I and II. Peaks appear in the early 1900s and again in the early 2000s. Plants follow a different path, with relatively steady rates over 150 years and renewed growth in recent decades.

Microbial life tells another story. Bacteria, archaea, and fungi show strong acceleration in the past 20 years. Improved genetic tools have made it easier to detect species that look identical but differ at the DNA level.

“Right now, most new species are identified by visible traits,” Wiens said. “But as molecular tools improve, we will uncover even more cryptic species; organisms distinguishable only on a genetic level.”

Insects show mixed patterns. Many major groups peaked in the early 1900s. Beetles and grasshoppers, however, continue to rise and reached record levels in the 2000s. Among vertebrates, fishes, amphibians, and lizards are still accelerating. Birds and mammals are not. Both peaked in the 1700s, and bird discovery rates have declined since.

“Our researcher team considered how many species scientists might formally describe by the year 2400. Using growth models that account for slowing over time, we projected that known animal species could reach about 2.6 million. Plants may exceed half a million species. Fungi could more than double their current total. Ray-finned fishes alone may surpass 110,000 described species, compared with about 33,000 today. Amphibians could grow fivefold,” Wiens shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“Some groups do not show signs of leveling off even by 2400. That suggests many species will remain unnamed well beyond that date. A second forecasting method predicted even larger increases, but we are treating those estimates cautiously,” he continued.

As Wiens also noted, “Right now, we know of about 2.5 million species, but the true number may be in the tens or hundreds of millions or even the low billions.”

The study also highlights challenges. Some species take years to appear in databases after description. Others later turn out to be duplicates of older names. Climate change may drive extinctions before species are ever described. These so-called dark extinctions leave no scientific trace.

Even so, the authors argue that the current pace of taxonomy is a bright spot. Fifteen percent of all known species were described in just the past 20 years. That fact alone reshapes how you should think about biodiversity.

“Even though Linnaeus’ quest to identify species began 300 years ago, so much remains unknown,” Wiens said.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists are discovering new species faster than ever, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.