A new study published in Brain Sciences provides evidence that dopamine promotes movement by directly altering the excitability of key neurons in the brain’s motor circuitry. The research identifies a specific ion channel, known as the inwardly rectifying potassium channel or Kir, as a critical mechanism through which dopamine activates behavior-promoting neurons in both healthy and Parkinsonian brains. The findings help resolve long-standing confusion over how dopamine affects these neurons and suggest that targeting Kir could offer new strategies for treating Parkinson’s disease.

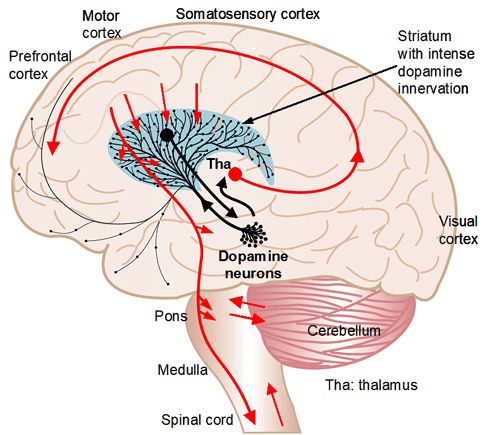

Dopamine is a chemical messenger that plays a major role in the brain’s reward, motivation, and motor systems. One of the brain regions most densely packed with dopamine signaling is the striatum, a central part of the basal ganglia network responsible for initiating and regulating movement. Within the striatum, two main types of neurons—direct pathway medium spiny neurons (also called D1-MSNs) and indirect pathway medium spiny neurons—work together to balance motion and rest. The D1-MSNs are stimulated by dopamine binding to D1-type receptors and tend to promote movement when activated.

The ability of dopamine to increase the activity of D1-MSNs is well-established at the behavioral level. When dopamine is depleted, as occurs in Parkinson’s disease, movement becomes severely impaired. Treatments such as L-dopa aim to restore dopamine levels and often restore mobility. Yet, despite decades of research, the precise cellular mechanism by which dopamine increases D1-MSN activity has remained controversial. Past studies offered conflicting results, with some suggesting dopamine reduces excitability of these neurons, which would not align with its known role in promoting movement.

To resolve this discrepancy, the researchers behind the new study turned to ion channels. These are microscopic gates in the neuronal membrane that control the flow of charged particles, helping regulate whether a neuron is at rest or fires an electrical signal. The Kir channel in particular is known to dampen neuronal activity by keeping the cell’s membrane potential low. If dopamine were to inhibit Kir, it would make the neuron more likely to fire. This study set out to test that hypothesis directly.

“I have been studying the brain dopamine system since 30 years ago, driven by the facts that loss of brain dopamine causes loss of motor function, i.e., Parkinson’s disease, and excessive brain dopamine activity can cause cognitive and behavioral abnormalities as demonstrated in schizophrenia and cocaine abusing. However, it was not known how dopamine produces these profound effects,” said study author Fu-Ming Zhou, a professor of pharmacology at the University of Tennessee College of Medicine.

“Based on our extensive past observations and experiments including failed experiments, we conducted our present study, a 5-year project that focused on medium spiny neurons in the striatum that receive intense dopamine innervation and express a high level of D1 type dopamine receptor.”

The research team used two different mouse models that mimic the loss of dopamine seen in Parkinson’s disease. One model lacked a gene essential for dopamine neuron development, while the other had a targeted knockout of tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme necessary to produce dopamine. These models allowed the researchers to examine how neurons respond to dopamine in a context where dopamine receptors are especially sensitive, due to the absence of normal dopamine levels.

To investigate how dopamine affects neuronal excitability, the team prepared brain slices from both normal and dopamine-depleted mice and conducted electrophysiological recordings on D1-MSNs. They applied dopamine directly to the brain tissue and measured the electrical properties of these neurons.

In slices from normal mice, dopamine had a modest effect. It caused a slight depolarization of D1-MSNs, meaning it made the cells slightly more excitable. Input resistance also increased, which means the neurons were more responsive to incoming signals. These effects were consistent with a moderate inhibition of Kir, supporting the idea that dopamine suppresses this potassium current to stimulate behavior-promoting neurons.

But in brain slices from dopamine-depleted mice, the effects of dopamine were much stronger. The D1-MSNs in these mice showed significantly greater depolarization, greater increases in input resistance, and a larger number of action potentials in response to stimulation. These hyperactive responses suggest that in the absence of normal dopamine signaling, D1-type receptors become sensitized, making the neurons far more responsive to dopamine when it is present.

To directly test whether the Kir channel was involved, the researchers used barium chloride, a known Kir channel blocker. When barium was applied, the excitatory effects of dopamine were largely eliminated. This indicated that dopamine’s action on D1-MSNs is mediated through Kir inhibition. Blocking Kir alone, without dopamine, also increased neuronal excitability, further strengthening this conclusion.

To confirm that Kir inhibition could also influence behavior, the researchers conducted experiments in live mice. They injected barium chloride directly into one side of the striatum in dopamine-deficient mice and observed increased movement, specifically contralateral rotation. This behavioral effect was similar to what is seen when dopamine agonists are injected.

When the researchers combined barium chloride with a D1 receptor agonist, the combined effect was not stronger than barium alone. This suggests that both treatments act on the same pathway and that Kir inhibition plays a central role in the behavioral effects of D1 receptor activation.

“We found that dopamine renders these neurons more excitable, allowing them to facilitate motor and cognitive neural circuits and related behaviors,” Zhou told PsyPost. “These findings are a solid step toward understanding the neuronal mechanisms underlying dopamine’s powerful regulation of brain function. The experiments were conducted in mice, but the brain dopamine system is highly conserved among mammalian animals including humans. So these new findings are likely applicable to humans.”

“Data in our present study and our prior studies show clearly and consistently that the dopamine system in the striatum is the main brain dopamine system and therefore is the main target of antipsychotic drugs, anti-Parkinson drugs, Ritalin (used to treat ADHD), and cocaine. A clear implication is that L-dopa doses (L-dopa is the precursor for dopamine) should be moderate for Parkinson’s disease patients; high L-dopa doses can overdrive the brain to produce excessive/abnormal motor activity and behavior.”

Previous studies have reported a wide range of findings regarding how dopamine influences D1-MSN activity. Some found that dopamine reduces excitability, while others reported no consistent effect. The authors suggest that many of these discrepancies can be explained by technical limitations or differences in experimental design. For instance, some studies used mixed populations of neurons that made it difficult to distinguish D1-MSNs from other types. Others may have applied dopamine in conditions that obscured its true effects.

By using genetically defined mouse models and recording from specifically identified neurons, the present study offers a clearer picture. It provides evidence that dopamine does increase the excitability of D1-MSNs and that this is primarily due to its inhibition of Kir channels.

“My long-term goal is to delineate, reliably, the anatomy, physiology and pharmacology of the striatal dopamine system (the brain’s main dopamine system), therefore contributing reliable knowledge that can be used to develop better treatments for brain diseases,” Zhou said.

The study, “Dopaminergic Inhibition of the Inwardly Rectifying Potassium Current in Direct Pathway Medium Spiny Neurons in Normal and Parkinsonian Striatum,” was authored by by Qian Wang, Yuhan Wang, Francesca-Fang Liao, and Fu-Ming Zhou.