A new study in Nature Physics ties together two ideas that long seemed to live in different corners of condensed matter physics. One is quantum criticality, the restless tipping point where a material cannot settle into a single state. The other is electronic topology, the math-like “twists” in an electron’s wave behavior that can make certain properties unusually robust.

The work was co-led by Rice University physicist Qimiao Si and Vienna University of Technology (TU Wien) physicist Silke Bühler-Paschen. Their teams argue that strong electron interactions can create a topological state, rather than destroy it, even in a regime where the usual picture of electrons as particle-like “quasiparticles” breaks down.

“This is a fundamental step forward,” said Si, the Harry C. and Olga K. Wiess Professor of Physics and Astronomy and director of Rice’s Extreme Quantum Materials Alliance. “Our work shows that powerful quantum effects can combine to create something entirely new, which may help shape the future of quantum science.”

Physicists often describe electric current using a simple mental model. Electrons behave like tiny objects with a position and a velocity. That picture stays useful in many metals, even complicated ones.

But quantum-critical materials can refuse to cooperate. Near a quantum critical point, electrons can fluctuate so strongly that they stop behaving like stable quasiparticles. In that case, the old “moving particles” story no longer fits.

At the same time, topological states usually come packaged with that same particle-like language. Many topological theories assume well-defined energies and velocities. That link has shaped how researchers search for topological materials, favoring systems where electrons act mostly independent.

The new research challenges that divide. “By merging these fields, we ventured into uncharted territory,” said Lei Chen, a Rice graduate student and co-first author. “We were surprised to find that the quantum criticality itself could generate topological behavior, especially in a setting with strong interactions.”

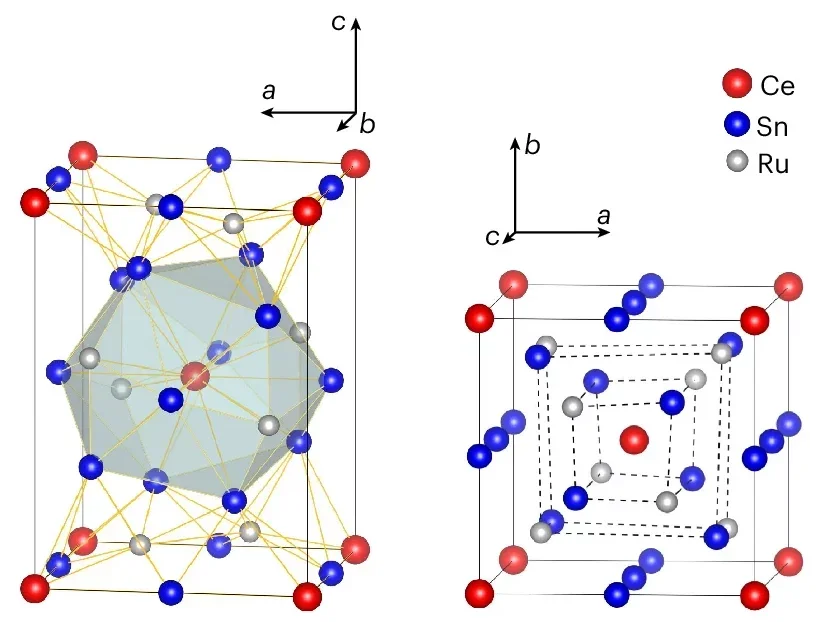

The central material in the study is CeRu₄Sn₆, made of cerium, ruthenium and tin. It belongs to a class called heavy-fermion compounds, where interactions make electrons behave as if they carry extra inertia. Those interactions can push a system toward unusual phases that do not show up in ordinary metals.

At TU Wien, Bühler-Paschen’s group examined CeRu₄Sn₆ at extremely low temperatures. The material sits close to a quantum critical regime, where it fluctuates between competing tendencies.

“Near absolute zero, it exhibits a specific type of quantum-critical behavior,” said Diana Kirschbaum, first author of the publication. “The material fluctuates between two different states, as if it cannot decide which one it wants to adopt. In this fluctuating regime, the quasiparticle picture is thought to lose its meaning.”

That statement sets up the problem. If quasiparticles lose meaning, then classic topological descriptions, built on neat electronic bands, should fail. Yet theory suggested CeRu₄Sn₆ might still host a topological semimetal state.

Topology comes from mathematics, and it classifies shapes by features that do not change under gentle deformation. A bread roll can deform into an apple shape, but not into a donut, because the donut’s hole cannot appear without tearing.

“In a similar way, states of matter can be described,” Bühler-Paschen said. She emphasized that topological properties can stay stable even when a material has defects or small distortions.

“For example, an apple is topologically equivalent to a bread roll, because the roll can be continuously deformed into the shape of an apple. A roll is topologically different from a donut, however, because the donut has a hole that cannot be created by continuous deformation.”

That robustness is why topological effects attract attention for quantum information, sensing and new ways to steer current. Still, many topological tools assume electrons behave like well-defined particles.

CeRu₄Sn₆ forced an uncomfortable question: could topology survive where the particle picture fails?

Kirschbaum decided to test the topological prediction directly, even though the system looked quantum critical. The team focused on a key fingerprint: a Hall effect, where voltage appears sideways to the current.

In standard Hall measurements, a magnetic field bends charge carriers and produces a transverse voltage. In CeRu₄Sn₆, the team saw a transverse response below about 1 kelvin even without an applied magnetic field.

They interpreted the signal as a spontaneous nonlinear Hall effect, consistent with topological behavior in a material that breaks inversion symmetry while keeping time-reversal symmetry. In simple terms, the sideways response can come from the material’s internal electronic geometry, not from an external magnet.

“What is particularly remarkable is that the charge carriers behave as if they were particles, even though the particle picture seems to fail in this material,” Bühler-Paschen told The Brighter Side of News. “This was the key insight that allowed us to demonstrate beyond doubt that the prevailing view must be revised.”

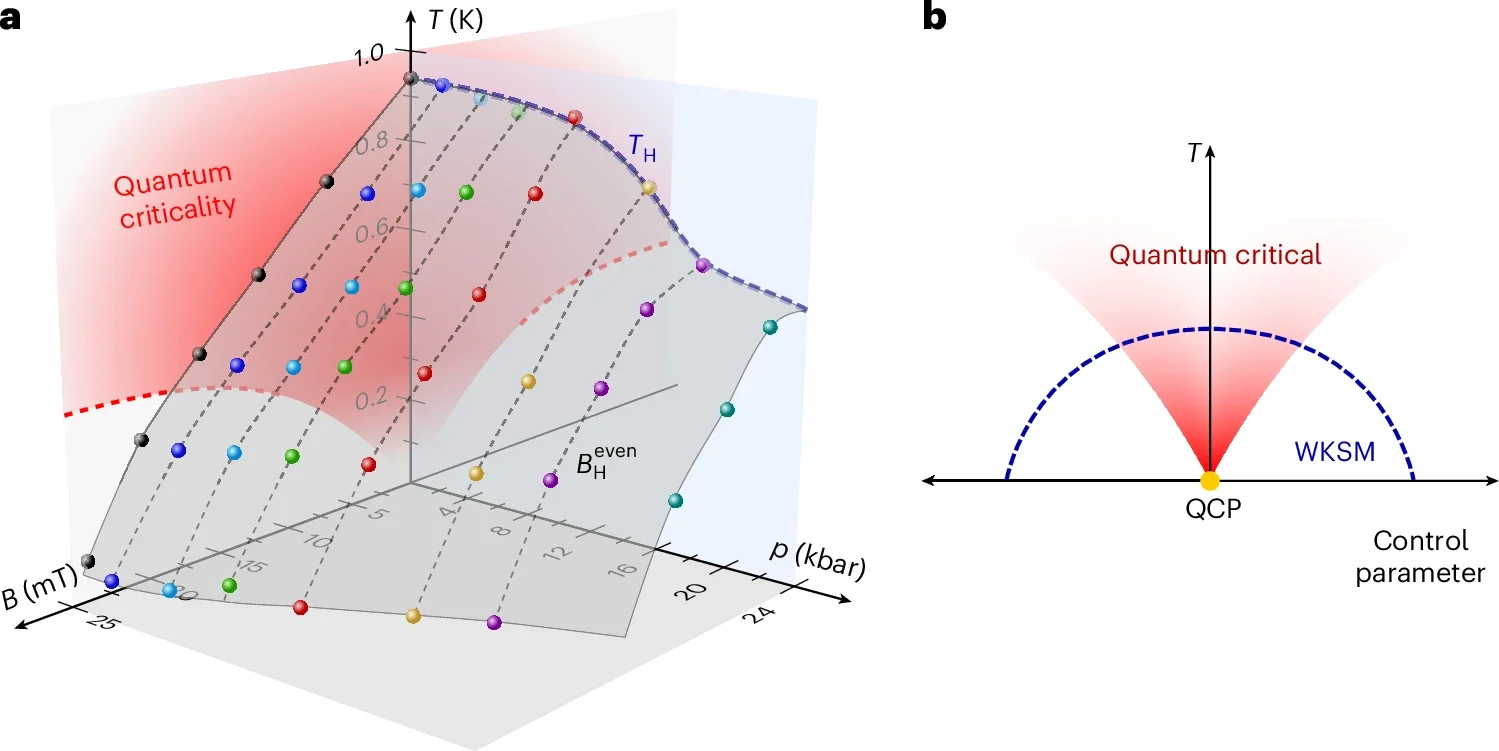

The measurements also showed something else. The topological response peaked where fluctuations were strongest. “And there is more,” Kirschbaum added. “The topological effect is strongest precisely where the material exhibits the largest fluctuations. When these fluctuations are suppressed by pressure or magnetic fields, the topological properties disappear.”

To probe the connection, the team tuned CeRu₄Sn₆ using hydrostatic pressure and magnetic field. Pressure pushed the system away from its most fluctuating state.

As pressure increased, the spontaneous Hall response weakened, and its onset temperature dropped. At high pressures, the effect became hard to detect. Magnetic field produced a similar pattern, suppressing the nonlinear Hall signatures tied to topology.

Taken together, the data supported a picture of a dome-like region where the topological semimetal state appears. The dome centers on the quantum critical regime, and it shrinks when pressure or field reduces the strongest fluctuations.

For researchers who hunt new quantum phases, that geometry matters. It suggests a practical clue: quantum criticality may point to where topology emerges, instead of hiding it.

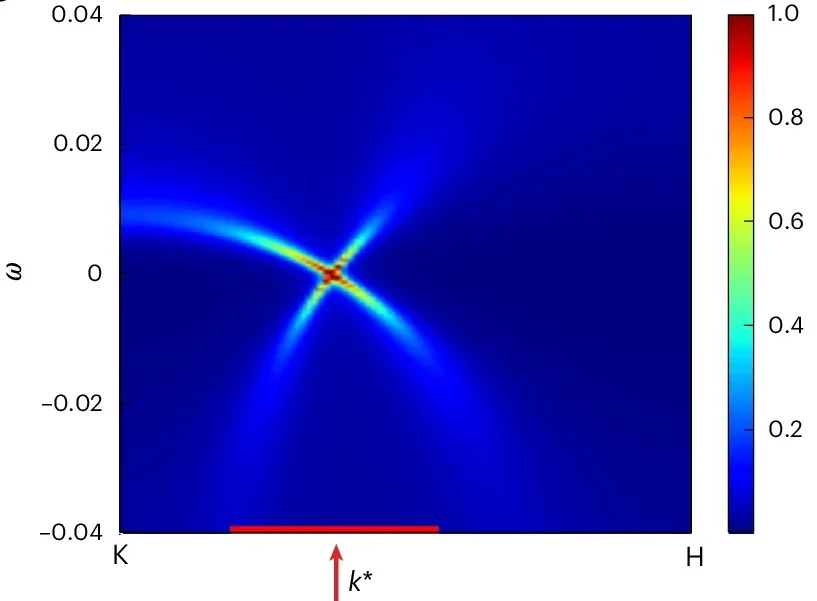

The study also confronts the theory problem head-on. Standard band topology relies on clean quasiparticle bands. But a Kondo destruction quantum critical point can erase quasiparticles.

The teams propose a broader approach. Rather than defining a topological node as a crossing of quasiparticle bands, they define it through the single-particle spectral function and the interacting Green’s function. In that framework, symmetry can still force crossings, and a generalized Berry curvature can remain meaningful.

“In fact, it turns out that a particle picture is not required to generate topological properties,” Bühler-Paschen said. “The concept can indeed be generalized; the topological distinctions then emerge in a more abstract, mathematical way. And more than that; our experiments suggest that topological properties can even arise because particle-like states are absent.”

For Si’s group, the message also cuts against an old assumption. “The findings address a gap in condensed matter physics by demonstrating that strong electron interactions can give rise to topological states rather than destroy them,” Si said. “Additionally, they reveal a new quantum state with substantial practical significance.”

This work offers a new strategy for finding quantum materials that combine stability with strong quantum behavior. Instead of starting with materials where electrons act nearly independent, future searches can focus on quantum-critical compounds where interactions run strong. That shift could widen the pool of candidate materials, because quantum criticality appears in many families of solids and can be identified with established measurements.

If researchers can reliably build or tune materials into this emergent topological regime, the payoff could reach beyond basic physics. Topological effects tend to resist disruption, and quantum-critical systems can amplify sensitivity to small changes in pressure, field or composition. Together, those traits could guide designs for more durable quantum components, ultrasensitive detectors, or low-power electronic concepts that rely on subtle electron behavior rather than brute-force current.

The deeper impact may be conceptual. By expanding topology beyond the quasiparticle picture, the study gives theorists and experimentalists a shared language for strongly interacting systems. That shared language can speed progress in materials science, where many promising compounds sit in the “messy” middle between simple metals and clean insulators.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Physics.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists discover new quantum state where electrons stop acting like particles appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.