Revisiting traumatic memories can take a toll on mental well-being, leaving individuals vulnerable to emotional distress and cognitive impairment. However, groundbreaking research reveals a promising solution: reactivating positive memories during sleep to diminish the grip of negative ones.

This innovative approach, known as targeted memory reactivation (TMR), leverages the brain’s natural memory-processing mechanisms during non-rapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep to alter how memories are stored and retrieved.

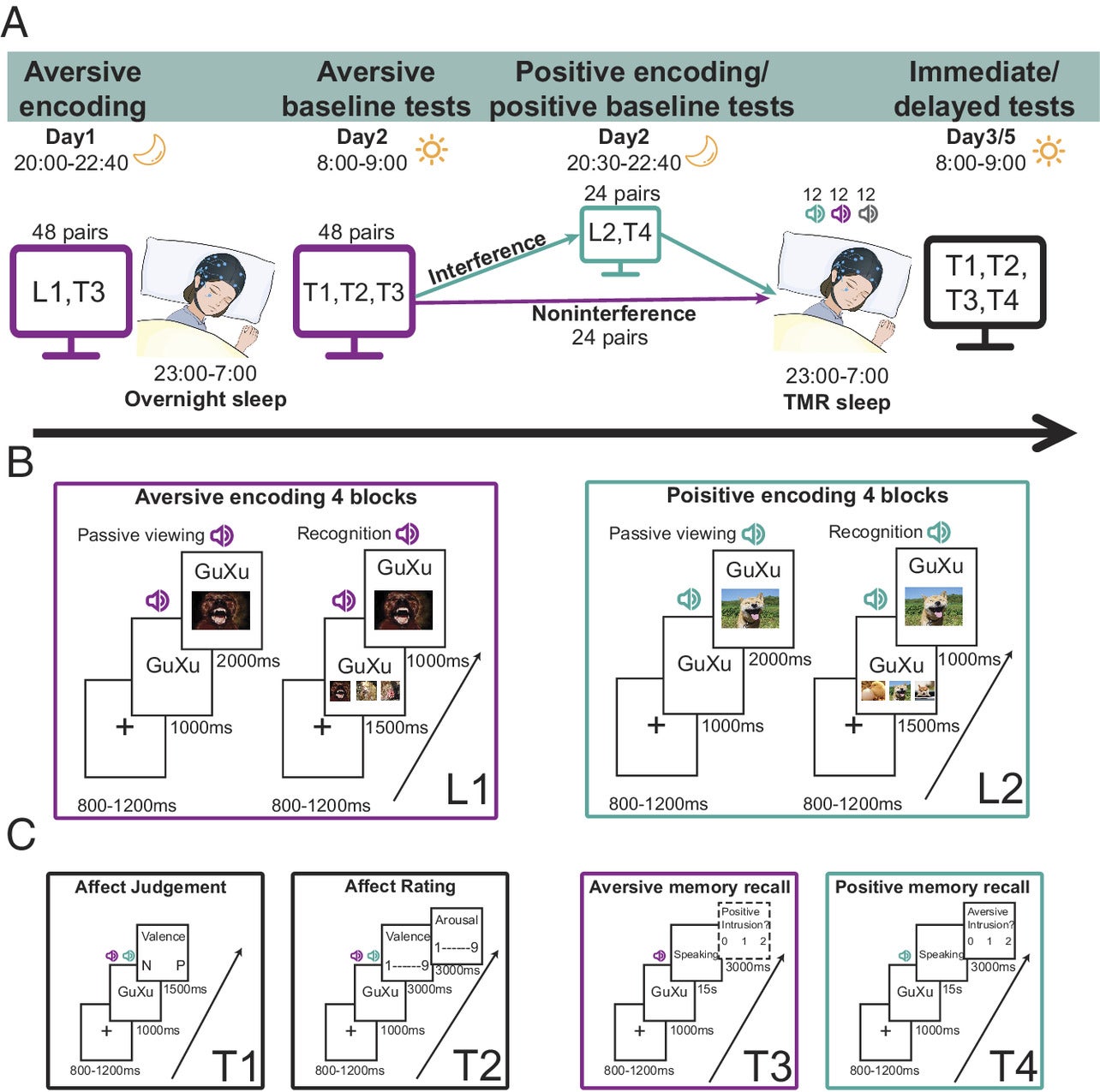

Researchers conducted a multi-day study involving 37 participants. On the first evening, participants formed associations between nonsense words and emotionally negative images, such as distressing scenes or threatening animals.

After a night’s sleep, these memories consolidated, becoming more entrenched. The next evening, participants were introduced to positive associations for half of the words, creating a set of “interfering” memories.

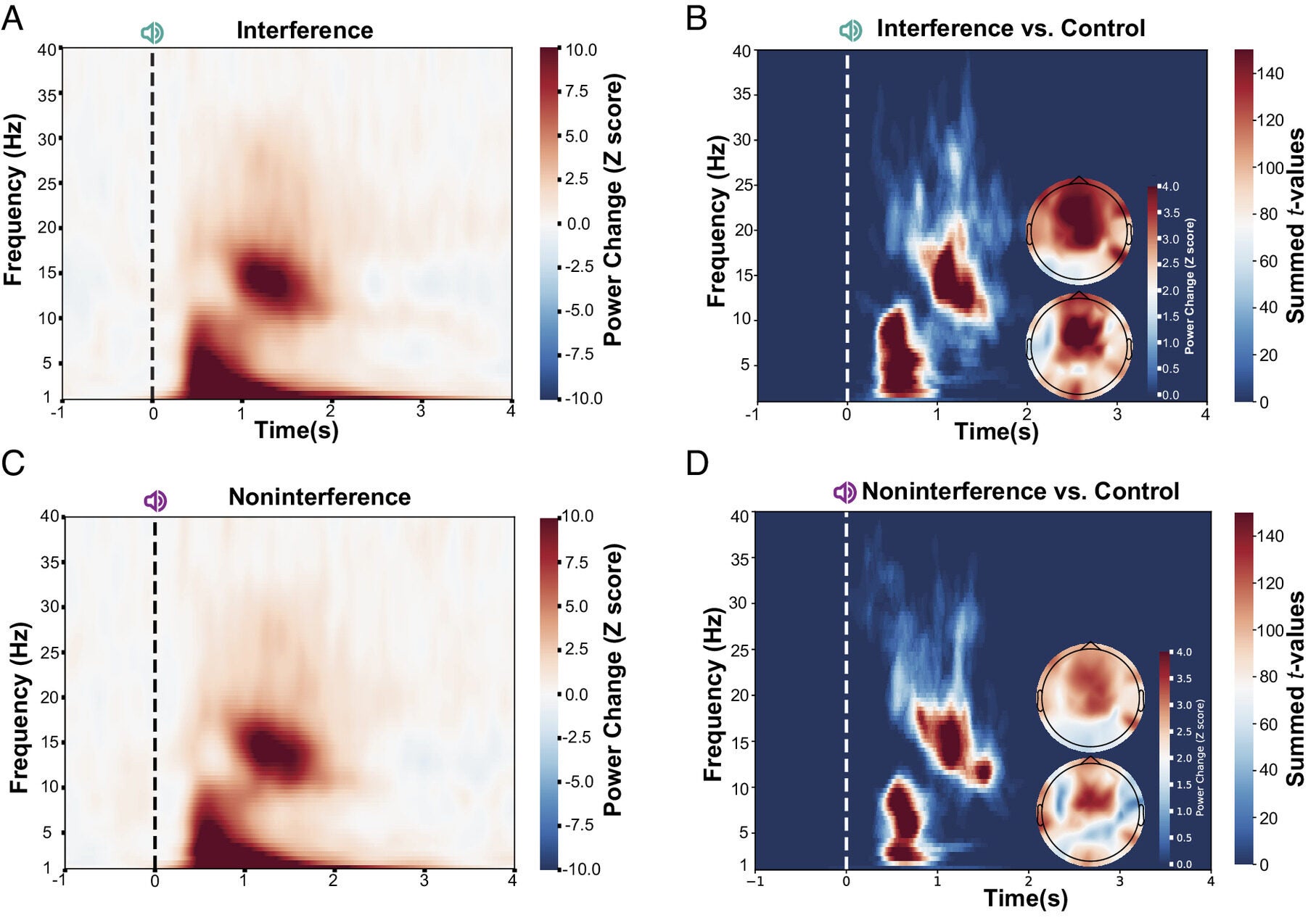

During the second night of sleep, researchers played auditory cues—the nonsense words—at low volumes to subtly trigger memory recall without waking participants. Electroencephalography (EEG) tracked brain activity, focusing on theta-band oscillations linked to emotional memory processing. These cues preferentially reactivated the newly created positive memories, gradually weakening the emotional intensity of the older, negative ones.

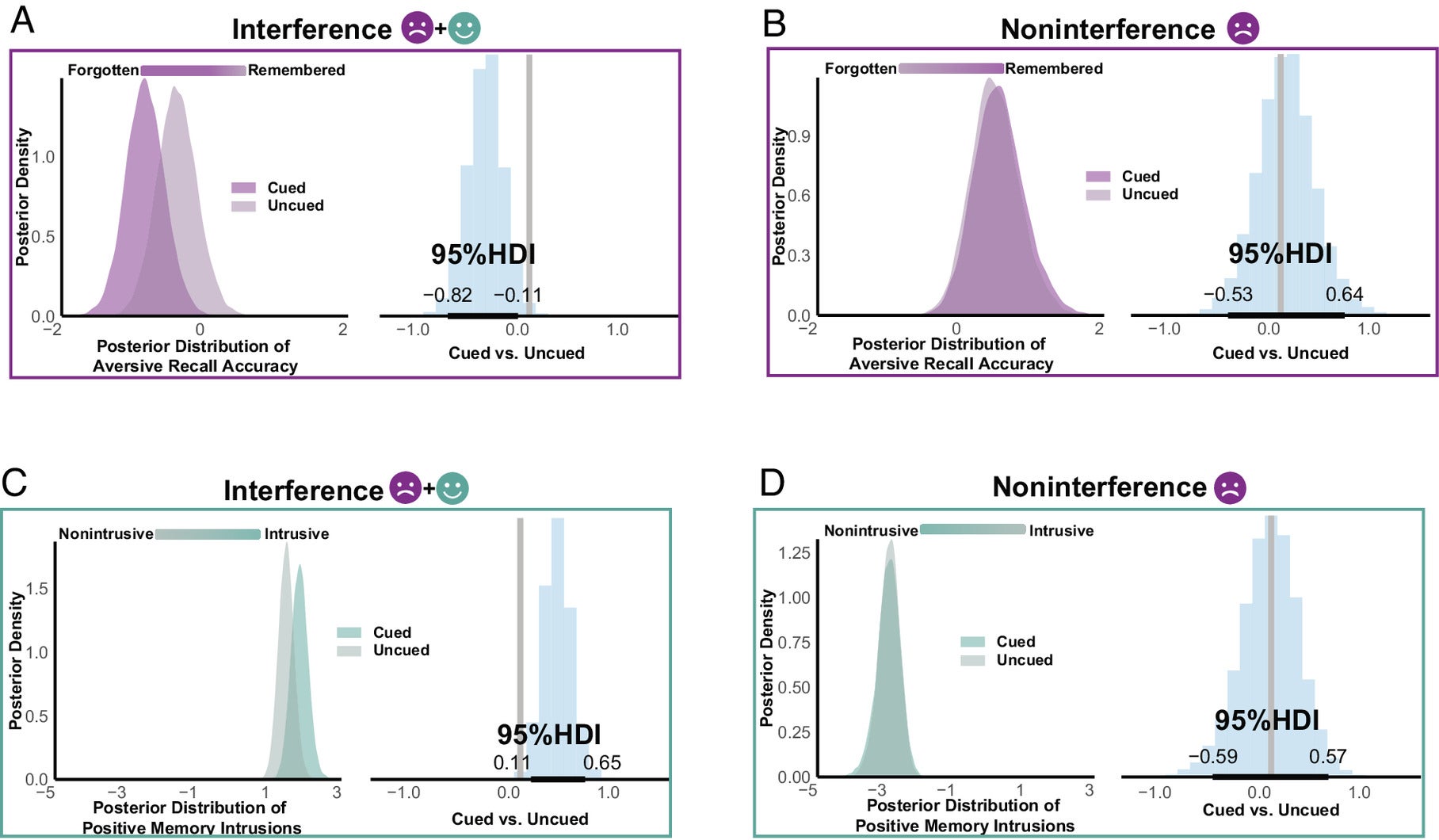

“We found that this procedure weakened the recall of aversive memories and also increased involuntary intrusions of positive memories,” the researchers reported in the journal PNAS. This noninvasive technique not only reduced the recall of negative memories but also fostered a positive emotional bias in participants’ responses.

Sleep has long been recognized as critical for memory consolidation. During NREM sleep, the brain replays daily experiences, reinforcing or weakening neural connections. Scientists have leveraged this natural replay process through TMR, which uses sensory cues to selectively influence memory consolidation. While TMR has primarily been explored to strengthen memories, this study highlights its potential for weakening distressing ones.

Related Stories

Prior research on emotional memory reactivation during sleep produced mixed results. Some studies showed that TMR could strengthen emotional memories or reduce arousal, while others found neutral or null effects. This research stands out by introducing positive interfering memories to counteract older aversive ones. The process effectively reactivates competing memories, shifting emotional responses toward positivity.

Theta-band activity in the brain emerged as a key player in this process. Higher theta activity correlated with increased positive memory recall and reduced negative memory recall. This suggests that theta rhythms during sleep are instrumental in the emotional reprocessing of memories.

The study’s design provided crucial insights into memory interference. By pairing half of the words with both positive and negative images, researchers created a competition between conflicting associations. Memory cues played during sleep selectively reactivated the positive associations, making them more dominant. Participants’ ability to recall the negative images weakened, while their recall of positive memories strengthened.

“Our findings open broad avenues for seeking to weaken aversive or traumatic memories,” the researchers stated. The implications are profound for individuals suffering from conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), where distressing memories disrupt daily life.

Importantly, the study avoided the use of medications, which often come with side effects. Instead, it demonstrated how sleep-based interventions could naturally modify memory storage. This approach aligns with existing therapeutic practices, such as exposure therapy, but introduces a novel dimension by leveraging sleep to reinforce positive experiences.

Despite its promise, the research has limitations. The emotional memories used in the experiment were artificially created in a controlled laboratory setting. Real-life traumatic experiences are far more complex and emotionally charged, making them harder to overwrite. The study’s findings must be validated with naturalistic or autobiographical memories to assess their applicability in real-world scenarios.

Additionally, the focus on NREM sleep leaves questions about the role of other sleep phases, such as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is known for emotional processing. Future studies could explore how different sleep phases interact with TMR to influence memory reactivation and emotional outcomes.

The long-term effects of this technique also remain unclear. While the study demonstrated that positive memory reactivation reduced negative recall up to five days later, further research is needed to determine whether these changes persist over months or years. Ethical considerations must also be addressed, particularly when applying memory-altering techniques to individuals with severe trauma.

“This study continues to show ways to treat these conditions without the use of medications, which oftentimes are fraught with adverse side effects,” noted Dr. Earnest Lee Murray, a neurologist unaffiliated with the study.

The potential of sleep to reshape emotional memories could revolutionize mental health treatments. By demonstrating that aversive memories can be weakened through positive interference, this research opens new pathways for managing trauma, depression, and anxiety. The findings underscore the brain’s remarkable capacity to adapt and heal during sleep.

“Our brains are unpacking, processing, and repacking emotions in our sleep,” said Dr. Alex Dimitriu, a psychiatrist and sleep medicine expert. He emphasized that interventions targeting specific sleep phases could significantly impact emotional well-being.

While challenges remain, the promise of TMR as a noninvasive, drug-free method for modifying memory highlights the need for continued exploration. Future advancements could refine these techniques, enabling clinicians to tailor interventions to individual needs.

As research progresses, the dream of easing emotional suffering through sleep moves closer to reality.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists discover sleep can ‘erase’ bad memories appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.