A research team at the British Museum, led by Nick Ashton and Rob Davis, reports evidence that ancient humans could make and manage fire about 400,000 years ago. The findings, published in Nature, come from East Farm Barnham in Suffolk, England. The discovery pushes strong evidence for deliberate fire-making back by about 350,000 years.

Until now, the oldest widely accepted signs of fire-making tools came from Neanderthal sites in northern France dated to about 50,000 years ago. Earlier sites in Africa and the Middle East show burning, but often in ways that could reflect natural fires. Barnham stands out because the signals look local, repeated, and maintained.

The work also includes outside perspective from the Natural History Museum. Professor Chris Stringer said: “The people who made fire at Barnham at 400,000 years ago were probably early Neanderthals, based on the morphology of fossils around the same age from Swanscombe, Kent, and Atapuerca in Spain, who even preserve early Neanderthal DNA.”

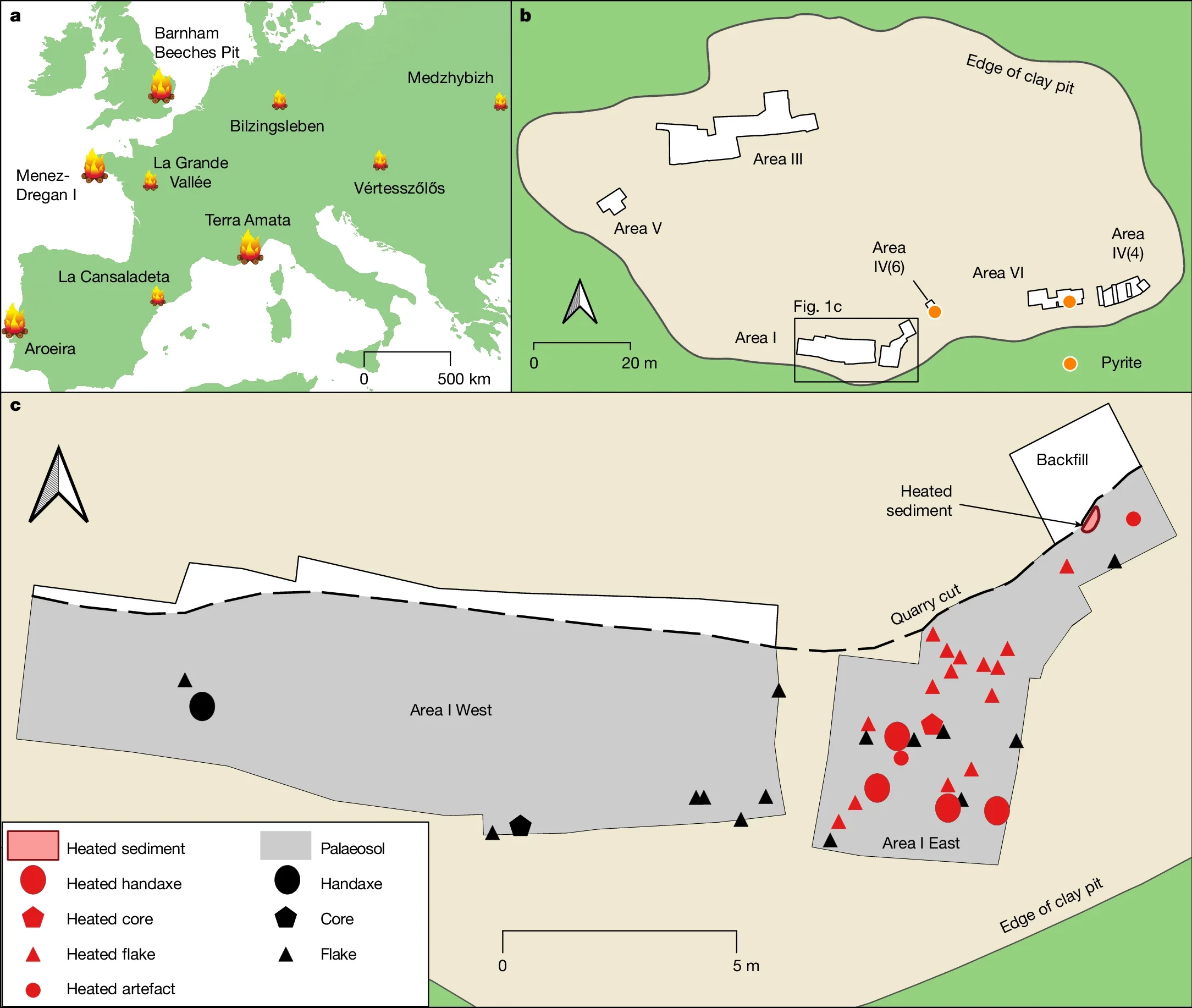

Barnham sits inside an old clay pit in the Breckland region. The site preserves sediments from a warm interglacial period after the Anglian glaciation. Those layers let researchers place artifacts within a clear time window, around marine isotope stage 11c.

Archaeologists identified two main occupations at the site. One includes cores and flakes in older sands and silts. Another, later occupation sits in an ancient soil layer and includes handaxes and debris from making them. Most heat-altered material clusters with this second occupation.

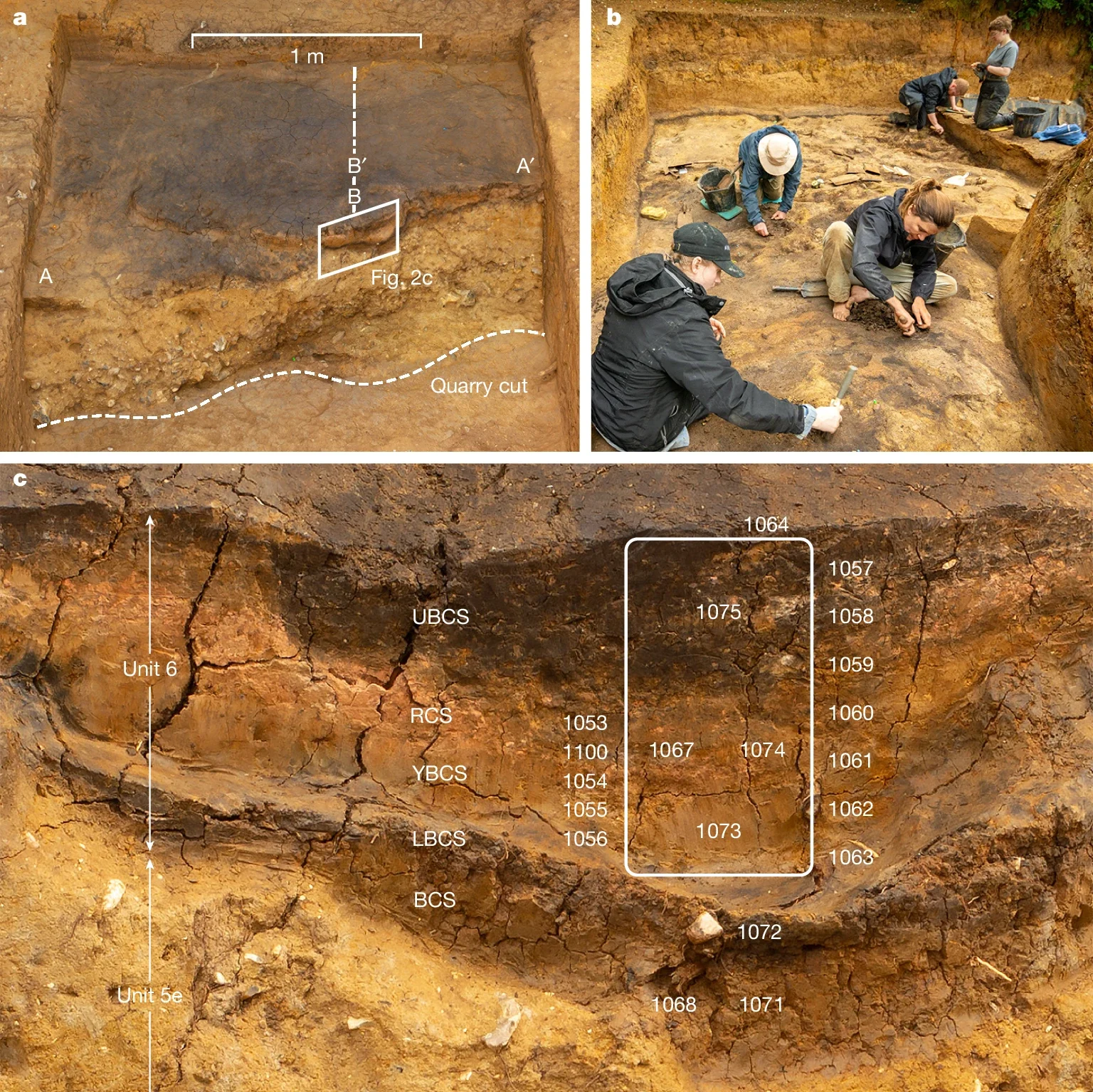

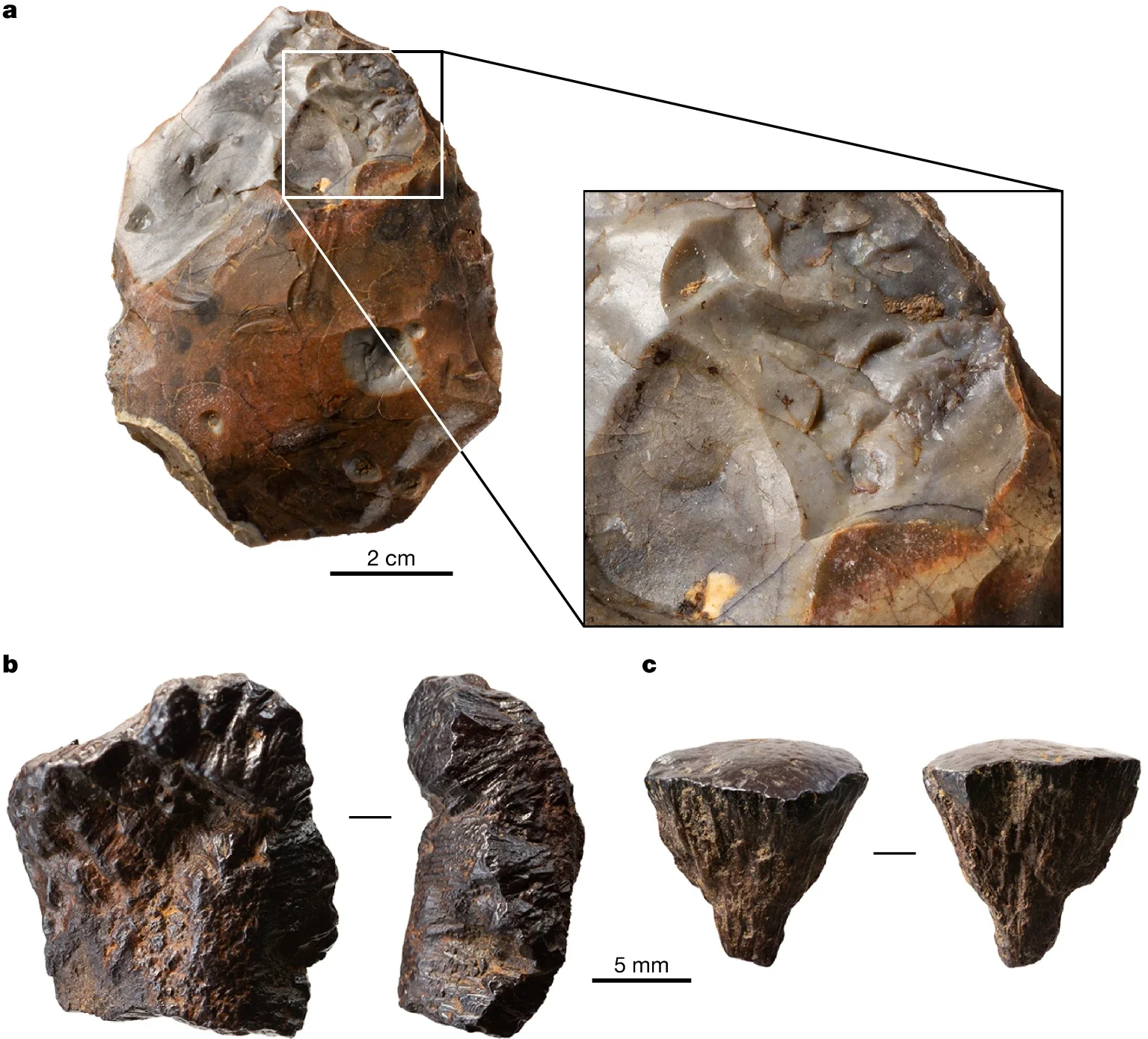

The key feature is a concentrated patch of reddened clayey silt inside that ancient soil. Excavators found the heated patch near an unusually dense cluster of stone artifacts. Many pieces show cracking, spalling, and color changes typical of strong heat. In the same zone, 76% of artifacts show clear signs of heating, including flakes, a core, and several handaxes.

Burned traces often vanish over time. Ash and charcoal can wash away or blow off. Heated sediment can erode. Even burned stone can be hard to interpret because wildfires also heat rock.

That is why the Barnham team spent four years testing whether the reddened patch came from a natural fire or repeated human activity. They used several approaches, each looking for a different fingerprint of burning.

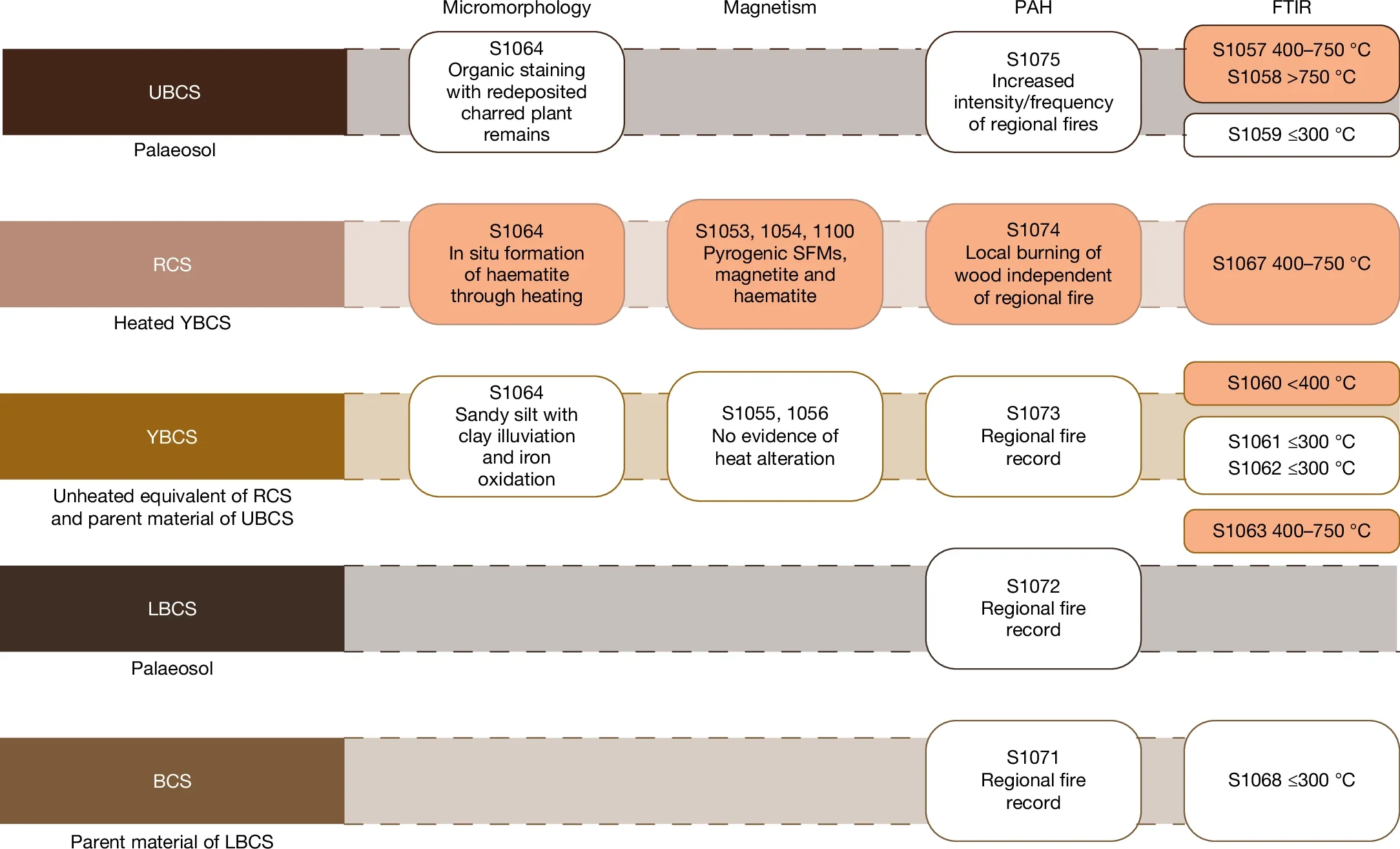

Microscopic sediment work linked the reddening to haematite formed through heating. The mineral pattern appeared uniform and in place, not dumped or transported. Samples taken beside the patch showed no heating, which points to a tight, localized heat source.

Magnetic tests found minerals consistent with burning and compared them with heating experiments. The pattern most closely matched many short heating events, not one long burn. Some mixing occurred later through soil processes, but the heated signature remained strong.

Chemical tests of smoke-related compounds also supported a hearth-like source. A sample from the reddened patch showed a higher abundance of heavier PAHs than nearby control samples. That profile fits localized wood burning more than regional wildfire smoke.

Infrared tests of clay minerals pointed to a range of heating, including samples consistent with very high temperatures. Some signals aligned with heating above 750°C. Together, the evidence supports repeated, confined burning in the same place.

“Our team found two small pieces of pyrite that had oxidized over time. Pyrite matters because it can be struck against flint to throw sparks into tinder. That method is well documented in experimental work and later archaeology,” Davis told The Brighter Side of News.

At Barnham, pyrite appears rare in local deposits. The researchers examined a large dataset of more than 121,000 clasts from 26 sites, including more than 33,000 from the Barnham area. None contained pyrite fragments. That absence strengthens the case that ancient visitors carried pyrite to the site rather than finding it underfoot.

One pyrite fragment came from the ancient soil in an area with heated flint and tools. The other lay on the soil surface and may have shifted. Even so, the combination of a maintained combustion feature, many heated artifacts, and imported pyrite supports an argument for deliberate ignition, not just careful use of a natural flame.

Ashton called the find personal and professional peak. “This is the most remarkable discovery of my career, and I’m very proud of the teamwork that it has taken to reach this groundbreaking conclusion.

“It’s incredible that some of the oldest groups of Neanderthals had the knowledge of the properties of flint, pyrite and tinder at such an early date.”

Davis emphasized the larger meaning. “The implications are enormous. The ability to create and control fire is one of the most important turning points in human history with practical and social benefits that changed human evolution.

“This extraordinary discovery pushes this turning point back by some 350,000 years.”

This work reshapes how researchers time key steps in human behavior. If early Neanderthal groups could ignite fire on demand, then planning, materials knowledge, and repeated domestic activity likely emerged earlier than many timelines suggest. That can change how archaeologists interpret older burned layers at other sites, including cases once dismissed as wildfire damage.

The findings also help explain how humans expanded into cooler, less predictable landscapes. Reliable fire supports warmth, protection, and safer food. Cooking can reduce pathogens and toxins, and it can make tough foods easier to digest. That shift may have freed energy for the brain and supported larger groups.

For future research, Barnham offers a blueprint for how to test ancient burning. The study shows the value of combining microscopic sediment work, magnetic signatures, chemical markers, and mineral changes.

That multi-test approach can help separate true hearths from natural burns at other early sites, tightening the story of how human life became more organized, social, and adaptable.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists discover the earliest evidence of human fire-making dating back 400,000 years appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.