The fate of the woolly mammoth is a story shaped by survival, isolation, and one final mystery still unsolved. Once scattered across the sweeping tundras of the Ice Age, these towering animals thrived in cold, open landscapes. But as the ice receded and their habitat shrank, their numbers thinned. In the end, a small group of them held on in one of the world’s most remote corners—Wrangel Island, off the coast of Siberia.

Cut off by rising sea levels nearly 10,000 years ago, the island became a frozen sanctuary for the last of the mammoths. A genetic study now suggests their story didn’t end in slow decline. Instead, something sudden and unexpected triggered their final collapse.

“This suggests that something else, and very sudden, caused the population to collapse,” said Marianne Dehasque, an evolutionary geneticist at Uppsala University and lead author of the study published in Cell.

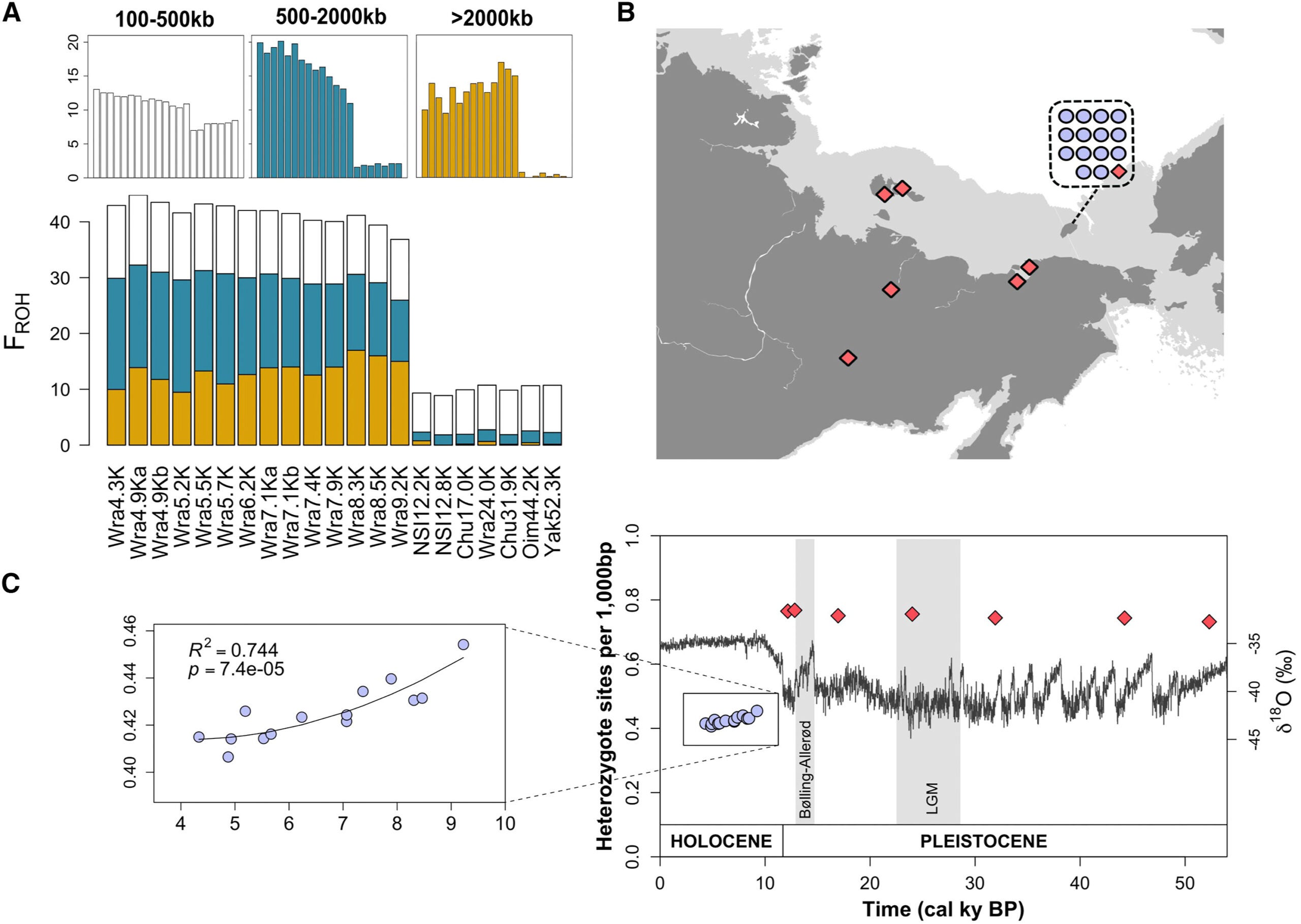

Dehasque and her team used ancient DNA to build the most detailed genetic timeline yet for the Wrangel Island mammoths. Their analysis found that the population likely began with just eight individuals.

Over the next few centuries, their numbers grew to roughly 200–300 and remained steady for more than 6,000 years. This stability, despite the challenges of inbreeding and isolation, hints at a population that adapted surprisingly well.

The genetic picture that emerged was more complicated than expected. The mammoths carried harmful mutations, and their genetic diversity was low—but not dangerously so. Some scientists had expected a sharp genetic decline, but the data told a more resilient story. Damaging mutations, especially the worst ones, were often removed naturally. Animals with severe defects reproduced less, slowly purging the gene pool of the most harmful changes.

Still, not all traits fared equally. Genes tied to the immune system stood out for their lack of diversity. That could have left the mammoths more prone to disease. On an island where help wasn’t coming, even a minor outbreak might have tipped the balance. But without direct evidence, researchers can only speculate.

Related Stories

A photograph from Wrangel Island captures a lonely tusk lying in a riverbed near Doubtful village—a quiet symbol of a species’ final chapter. The mammoths had survived climate shifts, genetic pressure, and centuries of isolation. What they couldn’t survive remains unclear.

The research, which analyzed genomes from 14 Wrangel Island mammoths and seven mainland ancestors dating back 50,000 years, found no evidence of a gradual genetic decline.

“If low genetic diversity or harmful mutations had doomed the population, we would expect a slow decline with increasing inbreeding,” explained Love Dalén, an evolutionary geneticist from the Centre for Palaeogenetics. “But this is not what we see. The population size was stable through time.”

The mammoths’ troubles began as the Ice Age ended. Rising global temperatures transformed their steppe tundra habitat into wetter forests, confining the species to northern Eurasia.

On Wrangel Island, mammoths adapted to the limited resources of their Arctic home. Stable population numbers over thousands of years suggest they managed well, despite the challenges of isolation.

“This is probably also how mammoths eventually ended up on Wrangel Island,” said Dehasque. “It may have even been a single herd that populated the island.” The genome data supports this, showing a remarkably small founding population that sustained itself through efficient adaptation.

Human involvement, a frequent cause of large mammal extinctions, seems unlikely in this case. Archaeological evidence shows humans arrived on Wrangel Island 400 years after the mammoths vanished. There is no indication of interaction, such as tools, fire hearths, or reworked bones. “The mystery of the mammoth’s demise continues,” Dehasque noted.

Inbreeding and genetic decline are also improbable causes. Over the 6,000 years of isolation, there was no significant increase in inbreeding or loss of genetic diversity. This stability is unusual for such a small population, defying expectations of genetic deterioration.

The study’s findings point toward a sudden and external cause for the mammoths’ extinction. One possibility is an infectious disease, potentially brought by birds, which might have exploited the reduced immune system diversity. Alternatively, environmental disasters such as tundra fires, volcanic activity, or extreme weather could have triggered a catastrophic loss of food resources.

“Given how small the population was, it would have been vulnerable to such random events,” said Dalén. A single season of poor plant growth on the island could have been enough to push the fragile population over the edge. “In other words, it seems to me that maybe the mammoths just got unlucky.”

The fate of Wrangel Island’s mammoths underscores the precarious balance small populations must maintain. While genetic adaptation can allow survival over long periods, environmental pressures and chance events can still have devastating effects.

For conservation efforts today, this serves as a sobering reminder of the challenges faced by species at the brink of extinction.

The woolly mammoths’ story is not just a tale of survival but also one of vulnerability. It reminds us that while science can illuminate the past, the intricate dance between genetics, environment, and luck continues to shape the natural world.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists discover what caused the woolly mammoth to die-off appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.