The first place tobacco often shows its damage is not the lungs. It is the mouth. If you smoke, your gums face a daily chemical assault. Over time, that can turn mild irritation into a chronic disease that loosens teeth and eats away at bone.

Scientists have long known smoking makes periodontitis worse. The condition is a severe, ongoing inflammation of gum tissue. It starts when microbes slip into the gums and the immune system reacts in an unhealthy way. As the reaction continues, gums pull back. The bone that anchors teeth weakens. Teeth can loosen and fall out.

Now, researchers say they have pinned down key cellular changes that help explain why smokers often develop faster, more severe disease. A team from Sun Yat-sen University in China used a high-resolution method to map gene activity in gum tissue.

The study points to a chain reaction that begins at the gum surface, spreads through support cells, then escalates through immune cells. At the center is one chemical signal, CXCL12, released by blood vessel cells. The researchers say it helps pull in immune cells and pushes them into a more harmful state. That signal could become a target for future therapies.

Your gums are not just padding around teeth. Periodontal tissue feeds teeth, defends against microbes, and helps teeth handle chewing forces. When it is healthy, it forms a tight barrier against the bacteria that live in the mouth.

Periodontitis breaks that barrier. The immune system tries to contain microbes that enter the tissue. In severe cases, the response does not calm down. Instead, it keeps smoldering for years.

Smoking makes this cycle harder to stop. Past research linked tobacco to changes in the epithelial barrier, fibroblast function, and immune responses. But the exact cell-by-cell mechanics stayed blurry. Older tools could not show where specific cell types sat in tissue, or how they “talked” to neighbors during disease.

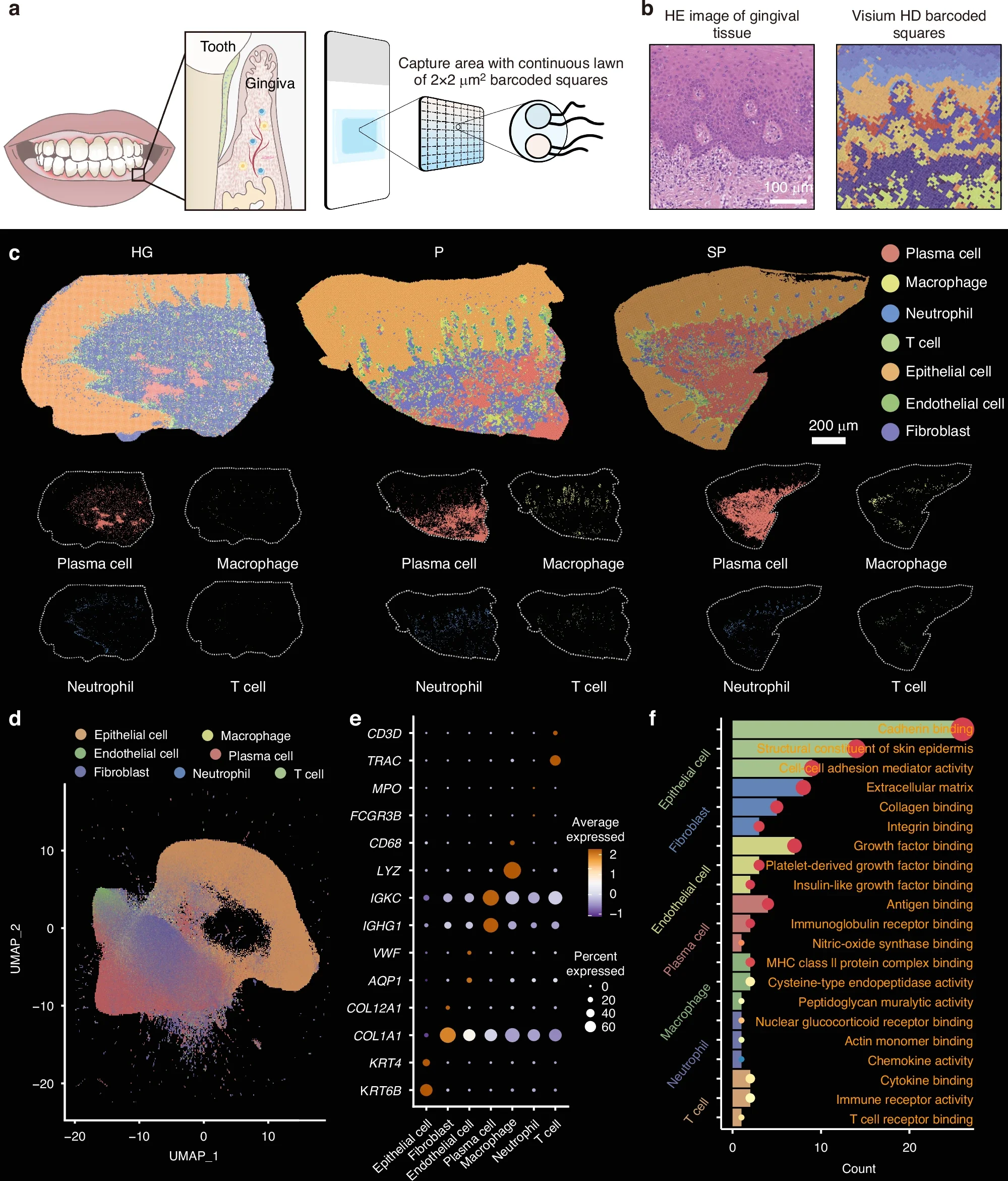

Professor Chuanjiang Zhao and colleagues used Visium HD single-cell spatial transcriptomics. That tool lets you measure which genes are active, and where that activity sits inside a tissue sample. It is like reading the gum’s molecular story while keeping the map intact.

“Understanding the complex cellular interactions that contribute to disease progression in smoking-associated periodontitis is important,” Zhao said. “By employing the Visium HD platform, we aimed to map the spatial distribution of different cell types within healthy and diseased periodontal tissues and identify smoking-induced changes in gene expression patterns across various cell populations.”

The team compared three groups: healthy gum tissue, non-smokers with periodontitis, and smokers with periodontitis. That allowed them to separate changes tied to disease itself from changes linked to smoking.

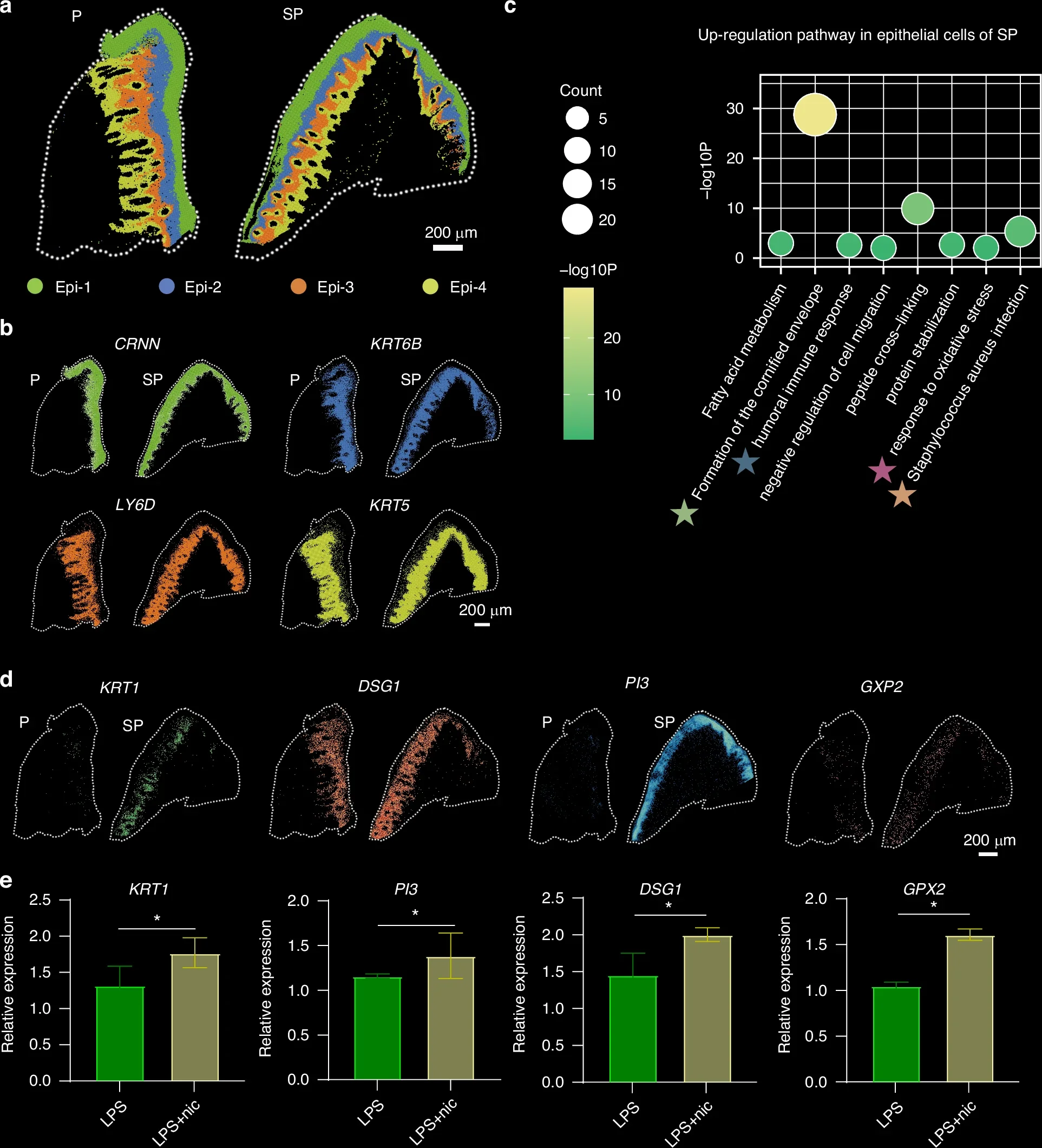

“The surface of your gums is made of epithelial cells. They form a seal. That seal matters because it blocks microbes and irritants from sinking deeper,” Zhao shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“To test how smoking compounds bacterial stress, our team first ran a targeted experiment. We exposed epithelial cells to bacterial lipopolysaccharide, also called LPS. Then we compared that to LPS plus nicotine,” he continued.

Nicotine changed the response. The combination produced larger shifts in genes tied to structure, barrier strength, cell-to-cell communication, and inflammation. In plain terms, nicotine appeared to make the gum surface more vulnerable. It also seemed to prime it for a stronger inflammatory reaction.

That matters because the earliest stages of gum disease often begin with barrier failure. Once microbes and their products cross the surface, the immune system must respond. In smokers, the study suggests, the surface may break down more easily, and the alarm signals may ring louder.

A weakened surface can also help explain why treatments work less well in smokers. Even after a dental cleaning or other care, an unstable barrier may keep letting triggers leak in.

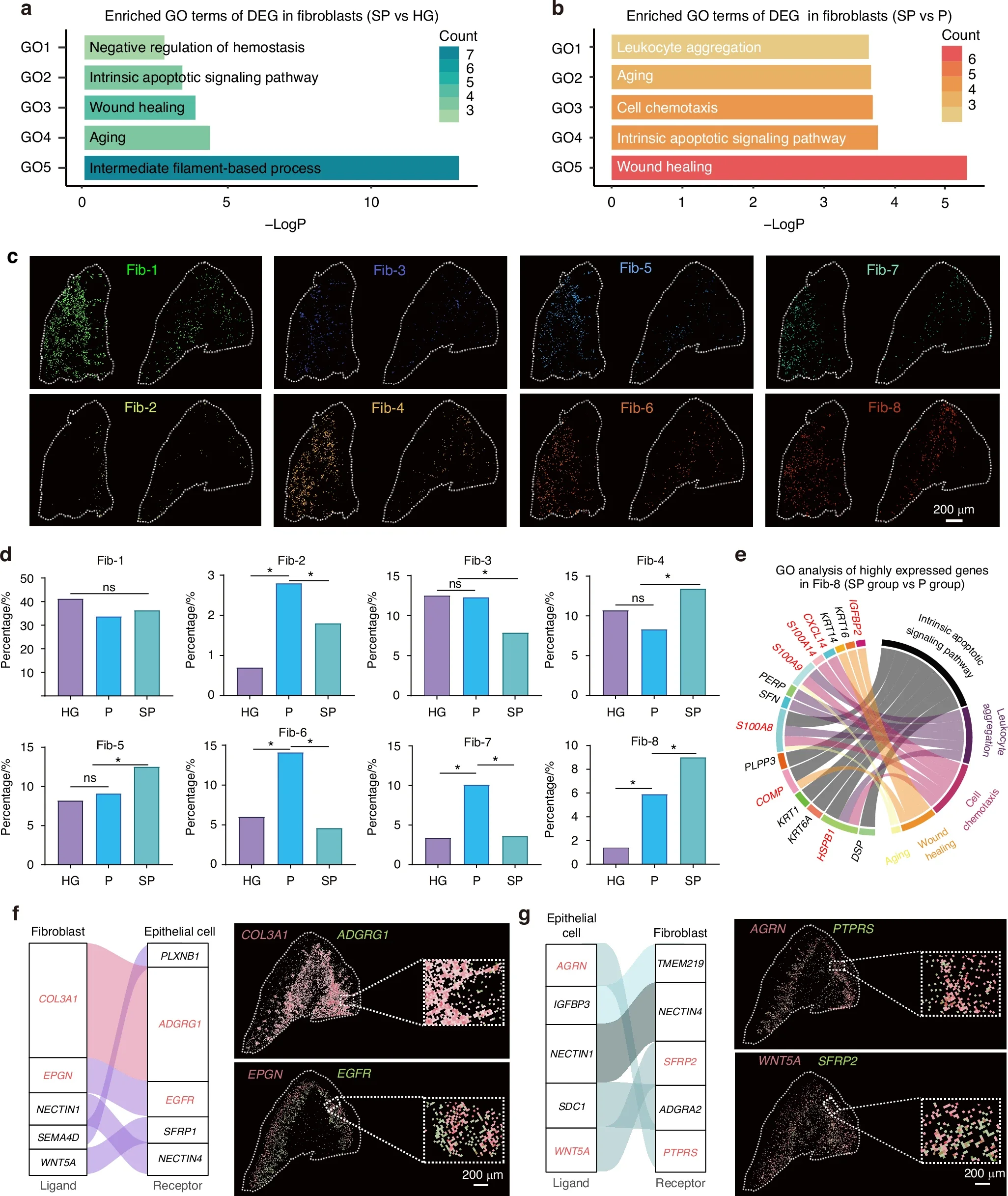

Below the surface, fibroblasts help keep gum tissue stable. They support structure and participate in repair. When they change, the whole system shifts.

The spatial gene maps showed fibroblasts in smoking-associated periodontitis carried a different molecular profile than fibroblasts in healthy gums. Zhao said the smoking group showed higher activity in genes tied to aging, intrinsic apoptosis signaling, and mitotic processes.

“Our results revealed that individuals in the smoking group, as opposed to healthy controls, presented upregulated expression of genes linked to ageing, intrinsic apoptotic signalling, and mitotic processes,” Zhao said.

The study also found fibroblasts in smokers showed higher expression of genes tied to inflammation and recruitment of immune cells. That detail matters because fibroblasts do not just hold tissue together. They also influence who enters the neighborhood.

If fibroblasts send out stronger “come here” signals, more immune cells arrive. That can help fight microbes at first. But in chronic disease, it can also mean more damage, more swelling, and more bone loss.

This shift may help explain the faster progression many smokers experience. The tissue support system may tilt toward stress and breakdown, instead of steady repair.

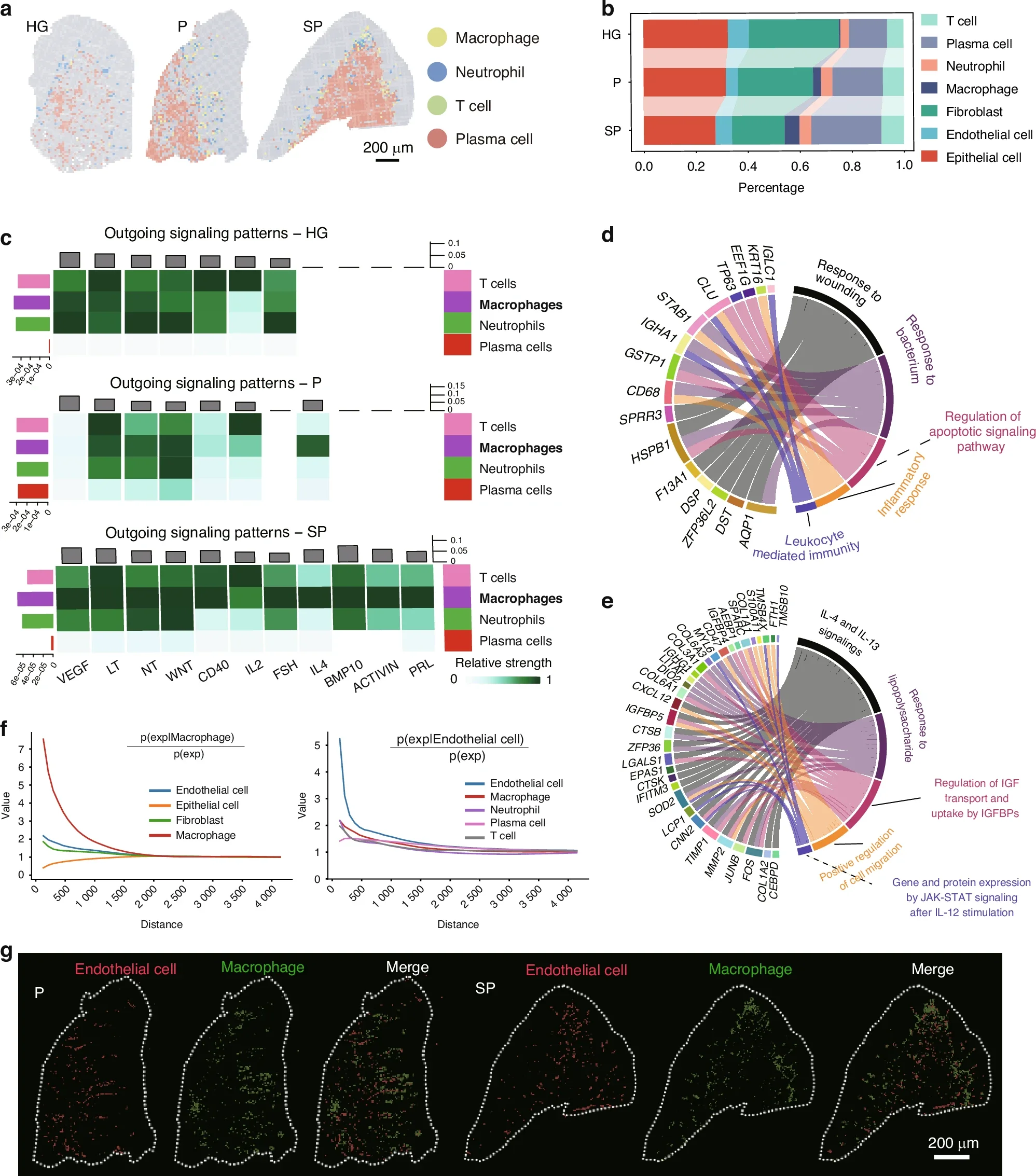

Inflammation is not just about how many immune cells appear. It is also about where they gather and how they interact.

The spatial maps revealed a striking pattern in smoking-associated disease. Endothelial cells, which line blood vessels, sat close to macrophages in smokers with periodontitis. That close positioning did not appear the same way in non-smokers.

Macrophages are immune cells that can either calm inflammation or intensify it. In smokers, the tissue contained a higher proportion of pro-inflammatory macrophages. The researchers describe these cells as central drivers of periodontal destruction.

The maps suggest smoking changes the tissue layout in a way that strengthens inflammatory cross-talk. When endothelial cells and macrophages sit side by side, signals from blood vessels can shape macrophage behavior more strongly. That can turn routine immune defense into a sustained attack.

The team traced much of that recruitment and activation to one molecule: CXCL12.

CXCL12 is secreted by endothelial cells. In the study, its presence supported macrophage recruitment and pushed macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory state. When the researchers suppressed CXCL12 secretion, macrophages shifted toward an anti-inflammatory profile.

That is a key pivot point. It suggests smoking does not only add more inflammation. It may reroute immune cells into a more damaging mode.

To test whether CXCL12 is more than a marker, the researchers went further. They used a mouse model of periodontitis aggravated by nicotine.

In that model, suppressing CXCL12 reduced inflammation and bone damage. The finding supports the idea that CXCL12 is not just present, but influential. It may function like a traffic signal that controls immune cell arrival and behavior.

The work does not claim a therapy is ready now. But it does point to a specific target. It also gives scientists a clearer explanation for why smoking-linked periodontitis can be so severe and so stubborn.

For many patients, gum disease feels like a slow loss of control. You brush. You floss. You show up for cleanings. Yet your gums keep pulling back. This study suggests smoking may be changing the tissue rules at a deep level, making calm healing harder to reach.

This study offers a clearer map of how smoking reshapes gum disease, and it highlights a promising treatment path. If future work confirms CXCL12’s role in human patients, therapies that reduce CXCL12 signaling could help blunt excessive inflammation in smokers with periodontitis. That could mean less tissue breakdown and less bone loss, even when quitting smoking is difficult.

The findings may also guide better risk tracking. By identifying gene patterns tied to weakened epithelial integrity, stressed fibroblasts, and pro-inflammatory macrophages, researchers can look for biomarkers that flag high-risk patients earlier. That could support more tailored care, including closer monitoring and more aggressive prevention for smokers.

Finally, the study shows the value of high-resolution spatial transcriptomics for complex diseases. By seeing which cells sit together and which genes turn on in place, scientists can move beyond broad labels like “inflammation.” They can pinpoint specific cellular relationships to target with precision.

Research findings are available online in the International Journal of Oral Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists discover why smoking loosens teeth and eats away at bone appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.