Plastics are deeply woven into modern life, valued for their strength, clarity, flexibility, and affordability. However, the production and disposal of these materials pose serious environmental threats. In 2022, global plastic production reached 400.3 million metric tons, much of it derived from petroleum-based processes.

These methods contribute to climate change and generate plastic waste that lingers in ecosystems for centuries. With growing concerns about sustainability, researchers are exploring biological alternatives—developing bacteria that can produce biodegradable polymers from simple carbon sources like glucose.

One of the most promising biopolymers under study is polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), natural polyesters that microbes store as energy reserves. PHAs have been recognized as a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics.

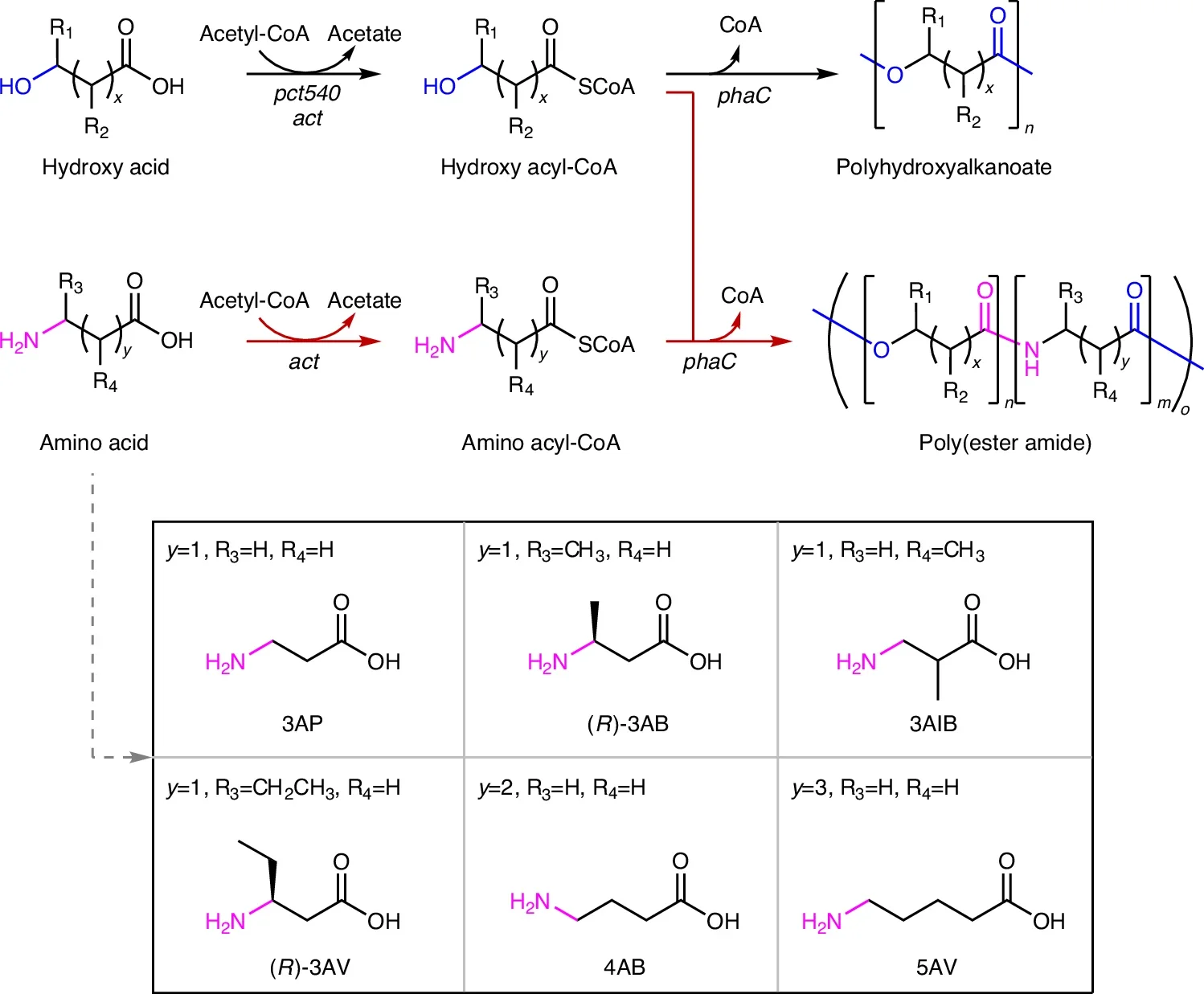

More than 150 hydroxy acid monomers can be incorporated into PHAs, allowing for adjustable material properties. The key enzyme responsible, PHA synthase (PhaC), links molecules through ester bonds, producing various forms of polyesters.

This bacterial system is flexible and capable of integrating different small molecules into its polymeric structure. Given this adaptability, researchers speculated that it might be possible to engineer bacterial strains to create poly(ester amide) (PEAs), a class of polymers with both ester and amide bonds.

These materials combine the mechanical strength of polyamides with the biodegradability of polyesters, making them suitable for both industrial and biomedical applications.

PEAs have traditionally been manufactured through chemical synthesis, but no natural biological pathways exist for their production. To overcome this, scientists sought to introduce synthetic metabolic pathways into bacteria, allowing them to generate these novel polymers from simple carbon sources.

Related Stories

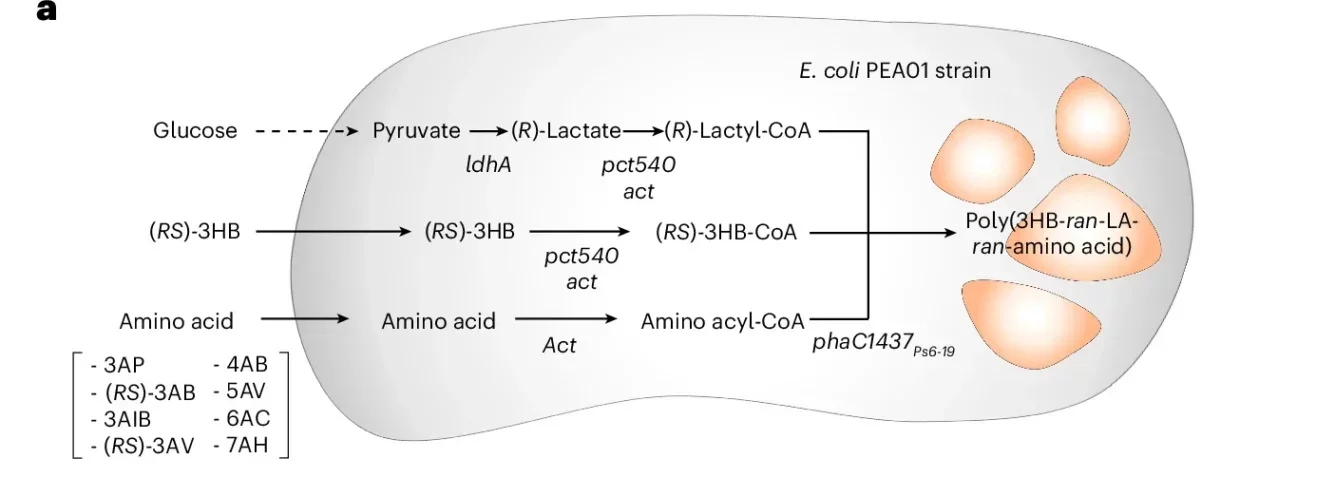

A team of researchers, led by Professor Sang Yup Lee at KAIST, focused on manipulating Escherichia coli to produce PEAs. Their approach involved introducing two key enzymes: one from Clostridium, which attaches molecules to coenzyme A (CoA), and another from Pseudomonas, a modified version of PHA synthase that could polymerize amino acid monomers. These enzymes enabled bacteria to create PEA precursors and link them into polymer chains.

Initially, the process was inefficient. One of the engineered enzymes was mildly toxic to E. coli, slowing its growth. To address this, researchers evolved bacterial strains that tolerated the enzyme better. The modified E. coli began producing small amounts of an amino acid-based polymer. Further refinements—such as adding extra genes to boost lysine production—improved polymer yields.

Another challenge involved reducing unwanted lactic acid incorporation into the polymer structure. Lactic acid is a natural byproduct of glucose metabolism and can form ester bonds, influencing polymer properties. By knocking out the gene responsible for lactic acid production, researchers minimized its presence, making the polymers more uniform.

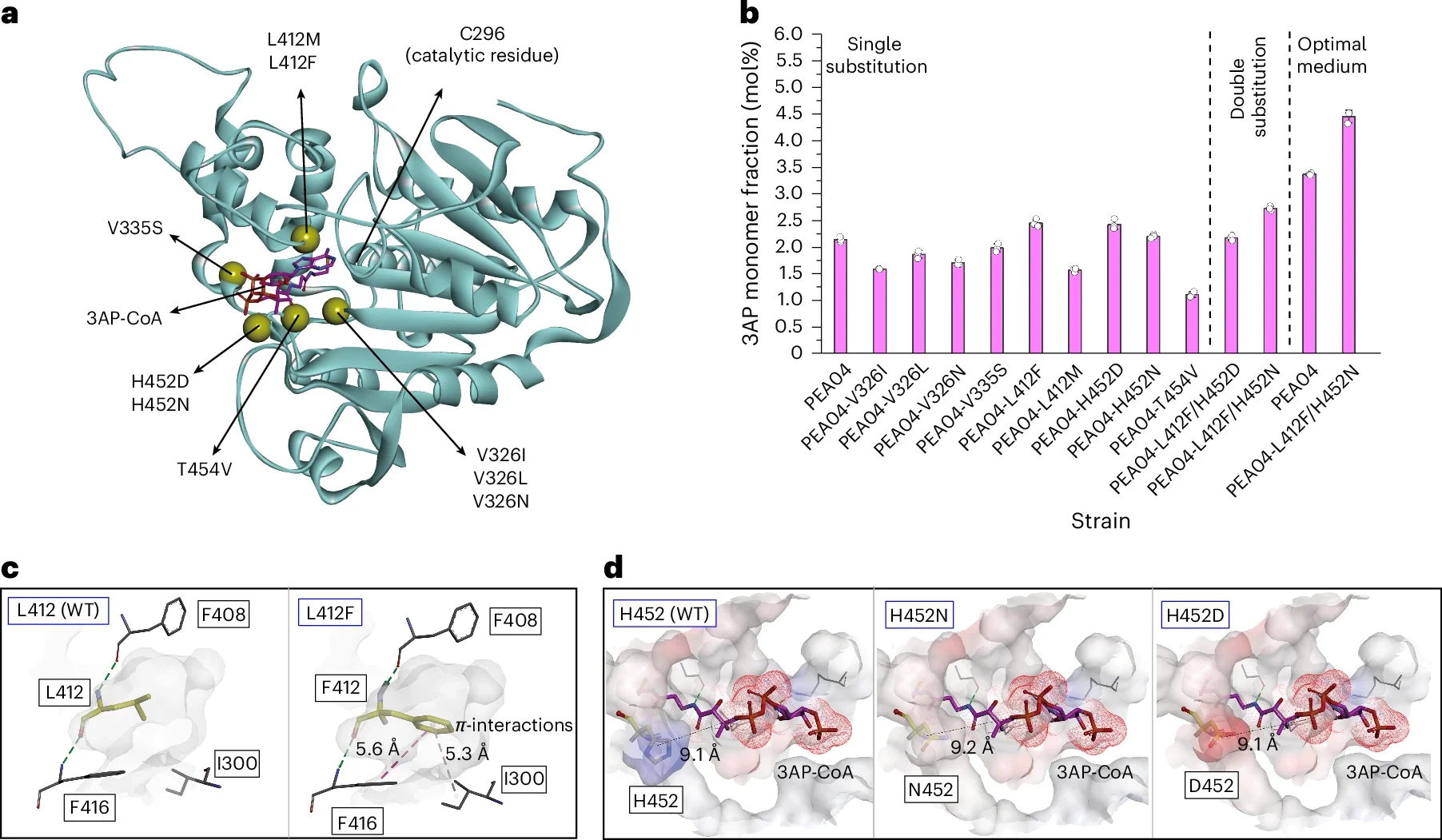

Through additional genetic modifications, the polymer yield increased significantly. At peak efficiency, the engineered bacteria converted over 50% of their dry weight into polymer. Further experiments showed that mutations in PHA synthase could bias polymer composition toward specific amino acids, allowing researchers to fine-tune material properties.

The ability to engineer bacteria for biodegradable plastic production is a major scientific breakthrough. These bio-based materials could reduce dependence on fossil fuels and mitigate plastic waste. The enzymatic bonds within these polymers make them naturally biodegradable, ensuring they break down more easily than traditional plastics.

Despite these advantages, several hurdles remain. The bacterial system does not allow complete control over polymer composition. While researchers can influence which amino acids or other chemicals are incorporated, the process remains somewhat unpredictable.

Additionally, separating the polymers from other bacterial byproducts remains a complex and costly step. Finally, the speed of bacterial polymer production is significantly slower than large-scale industrial methods.

While these bioengineered plastics are not yet ready to replace traditional plastics on a global scale, they highlight the vast potential of biological manufacturing. With further refinement, bio-based polymers could become a viable alternative, paving the way for a more sustainable future.

Scientists continue to explore enzyme engineering, metabolic pathway optimization, and large-scale fermentation techniques to improve efficiency and scalability.

Biotechnology is revolutionizing material science, offering solutions to one of the world’s most pressing environmental challenges. By harnessing the power of microbes, researchers have taken a significant step toward producing biodegradable, petroleum-free plastics.

Though there is still work to be done, bio-based polymer production holds the promise of reducing waste, lowering carbon emissions, and moving industries toward a more sustainable model.

As efforts continue, collaboration between scientists, policymakers, and industry leaders will be essential to bring bio-based plastics to commercial viability.

The journey toward sustainable plastics has begun, and with each breakthrough, the vision of a world free from persistent plastic waste comes closer to reality.

Research findings were published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists engineer bacteria to replace fossil-fuel-based plastics appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.