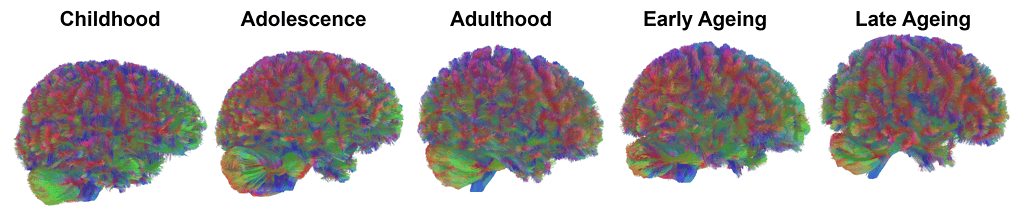

New research indicates that the structural organization of the human brain does not develop in a continuous, linear fashion but rather progresses through five distinct phases separated by specific turning points. By analyzing brain scans from thousands of individuals ranging from infants to ninety-year-olds, scientists identified significant shifts in neural architecture occurring around ages nine, 32, 66, and 83.

These findings, published in Nature Communications, provide a new framework for understanding how the brain reorganizes itself throughout the human lifespan and suggests that structural adolescence may extend well into the third decade of life.

Previous research has established that brain structure and function evolve as people age. However, many of these studies focused on specific developmental windows, such as early childhood or old age, rather than the entire life course. When studies did examine broader age ranges, they often relied on models that assumed smooth, gradual trajectories, such as a simple peak in adulthood followed by a steady decline.

The authors of the new study argued that these approaches might miss complex, non-linear shifts in how the brain is organized. By mapping these structural changes across the full spectrum of life, the research team aimed to create a baseline for typical development.

“We know that the brain changes it’s connections across the lifespan, however, we’ve lacked clarity on the general patterns of these changes. This is important information because the way the brain is wired is related to neurodevelopment, mental health disorders, and neurological conditions,” said study author Alexa Mousley, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Cambridge.

“Therefore, knowing what the brain is expected to be doing at specific points in time, we might better understand what the brain is best at or most vulnerable to specific ages. For example, 2/3rds of people who will develop a mental health disorder do so before the age of 25.”

To construct this lifespan trajectory, the researchers aggregated data from nine distinct neuroimaging datasets. This compilation resulted in a total sample of 4,216 individuals, aged zero to 90 years. From this larger group, the team analyzed a subset of 3,802 scans from neurotypical individuals to establish a standard model of development.

The researchers utilized diffusion-weighted imaging, a type of MRI that tracks the movement of water molecules in brain tissue. This method allows scientists to map white matter tracts, which serve as the cabling system connecting different regions of the brain.

The research team employed graph theory to analyze the organization of these brain networks. They calculated twelve specific metrics to describe the topology of the brain. Topology refers to the way parts of a network are arranged and connected.

Key metrics included global efficiency, which measures how easily information can travel across the whole network, and modularity, which assesses how well the network is divided into specialized, self-contained communities.

To make sense of this high-dimensional data, the researchers utilized a machine learning technique known as Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). This method projects complex, multi-variable data into a lower-dimensional space, allowing researchers to visualize distinct patterns and trajectories.

By analyzing these projections, the research team developed an algorithm to identify “turning points.” These points represent ages where the trajectory of brain development shifts significantly, indicating a transition from one phase of organizational change to another.

The analysis revealed four major turning points across the lifespan, occurring approximately at ages nine, 32, 66, and 83. These boundaries define five distinct epochs of structural development.

The first epoch spans from birth to age nine. This period corresponds with rapid changes in brain volume and the consolidation of neural networks. In early childhood, the brain overproduces synapses, which are subsequently pruned back to remove weak or unnecessary connections.

The study data indicates that topological efficiency decreases during this phase, while local segregation increases. The turning point at age nine aligns with the typical onset of puberty and significant increases in cognitive capabilities.

The second epoch, lasting from age nine to 32, represents a prolonged period of “adolescence” in terms of brain structure. During this phase, the brain focuses on increasing network integration.

The researchers observed that connections became more efficient, allowing for rapid communication across the entire brain. This period is characterized by a rise in “small-worldness,” a property where a network is both highly clustered locally and efficiently connected globally.

The turning point at age 32 was identified as the strongest shift in the entire lifespan. It marks the end of the period where efficiency increases and signals a transition into a new trajectory.

The third epoch extends from age 32 to 66, covering the majority of adulthood. In contrast to the rapid changes of the previous epoch, this phase is characterized by relative stability and a plateau in network integration.

The dominant trend during these years is an increase in segregation, meaning brain regions become more compartmentalized. This period aligns with observations from psychological research suggesting that personality and fluid intelligence tend to stabilize during middle adulthood.

The fourth epoch runs from age 66 to 83, labeled as early aging. The turning point at age 66 coincides with the typical onset of age-related health conditions, such as hypertension, which can impact brain health.

During this phase, the researchers observed a decline in the network integrity that was built up earlier in life. The trajectory shifts toward a simplification of the network structure, often associated with the degeneration of white matter connections.

The final epoch identified in the study begins at age 83 and extends to age 90, the upper limit of the sample. This late aging phase is marked by further reductions in global connectivity.

The topology of the brain shifts such that the importance of individual nodes in the network becomes more critical than the global connections. The researchers noted that the relationship between age and topological organization appears to weaken in this final stage, although the sample size for this oldest group was smaller than for younger groups.

One of the most notable outcomes of this analysis is the alignment of these structural turning points with major biological and social milestones. The shift at age nine corresponds with the beginning of hormonal changes associated with puberty and increased vulnerability to mental health issues.

The turning point at 32 aligns with the cessation of white matter growth and the peak of certain physical capabilities. The shift at 66 matches the retirement age in many societies and the increased prevalence of cognitive decline.

The findings indicate that “the brain develops non-linearly – it’s not one steady increase or decline,” Mousley told PsyPost. “The brain goes through phases where it changes differently than at other points in the lifespan.”

While the study provides a comprehensive overview of population-level trends, it contains limitations inherent to its design. The research utilized cross-sectional data, meaning it compared different individuals at different ages rather than tracking the same individuals over time. Consequently, it remains unclear if every individual follows these exact trajectories or if the turning points vary significantly from person to person.

The researchers also noted that the study focused exclusively on brain structure. The findings describe how neural “hardware” changes but do not directly measure behavior, maturity, or cognitive ability.

The extension of the “adolescent” structural phase to age 32 does not imply that individuals in their thirties exhibit adolescent behavior, but rather suggests that their brain networks are still optimizing for efficiency in a manner similar to younger adults.

“Many people are interested in the finding that adolescence goes until around 32 years old,” Mousley said. “It is important to note that we ONLY studied changes in brain architecture. Therefore, our work does not support anything about behavior or cognition.”

The researchers suggest that future research should apply these methods to longitudinal datasets to validate the trajectories at the individual level. Additionally, investigating how these topological turning points differ in individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders or mental health conditions could provide new insights into the biological underpinnings of these challenges.

The study, “Topological turning points across the human lifespan,” was authored by Alexa Mousley, Richard A. I. Bethlehem, Fang-Cheng Yeh, and Duncan E. Astle.