Cells do more than carry out chemical reactions. New theoretical work suggests they may also generate usable electrical energy through constant motion in their membranes, offering a fresh way to think about how biology powers itself.

Researchers at the University of Houston and Rutgers University report that tiny ripples in the fatty membranes surrounding cells could create voltages strong enough to support important biological tasks. Their study focuses on how active motion inside cells, driven by energy-consuming proteins, may turn membrane bending into a source of electrical power.

“Cells are not passive systems; they are driven by internal active processes such as protein activity and ATP consumption,” the researchers write. “We show that these active fluctuations, when coupled with the universal electromechanical property of flexoelectricity, can generate transmembrane voltages and even drive ion transport.”

Inside living cells, membranes constantly bend, stretch, and ripple. Some of this motion comes from heat, but much of it comes from proteins that consume adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the cell’s main energy currency. These proteins push and pull on membranes as they work, creating motion that is not random in time.

The study examines how that motion interacts with flexoelectricity, a property found in all dielectric materials. When a material bends, its electrical charges can shift, creating polarization and voltage. In biological membranes, which bend easily, this effect offers a direct link between mechanical motion and electrical signals.

This idea differs from better-known effects like piezoelectricity, which requires rigid crystal structures rarely found in cells. Flexoelectricity works in soft, fluid membranes and operates in both directions. Bending creates electrical changes, and electrical changes can influence bending.

Thermal ripples alone cannot power anything useful. At equilibrium, random motion cancels itself out. The researchers argue that living cells are never in equilibrium. Their internal activity breaks that balance, opening the door to harvesting energy from motion that looks random but is actually time-correlated.

To test this idea, the team built a theoretical model of a cell membrane that includes both mechanics and electricity. The model tracks how the membrane bends and how electrical polarization responds. It also includes two kinds of noise. One comes from thermal motion. The other comes from active forces generated by proteins that consume energy.

The researchers treated active proteins as drivers of membrane bending. Electrical effects follow through flexoelectric coupling. This choice allowed them to isolate how mechanical activity alone could produce electrical output.

Because the system is not in equilibrium, a standard free energy does not exist. Instead, the researchers used an energy-like function that captures steady-state behavior. This approach let them predict how average properties of the membrane change when active motion is present.

The calculations consider realistic cell dimensions. The membrane thickness is set at about five nanometers, and the membrane spans micrometer-scale regions. Known values for membrane stiffness, surface tension, dielectric properties, and electrical resistance are included.

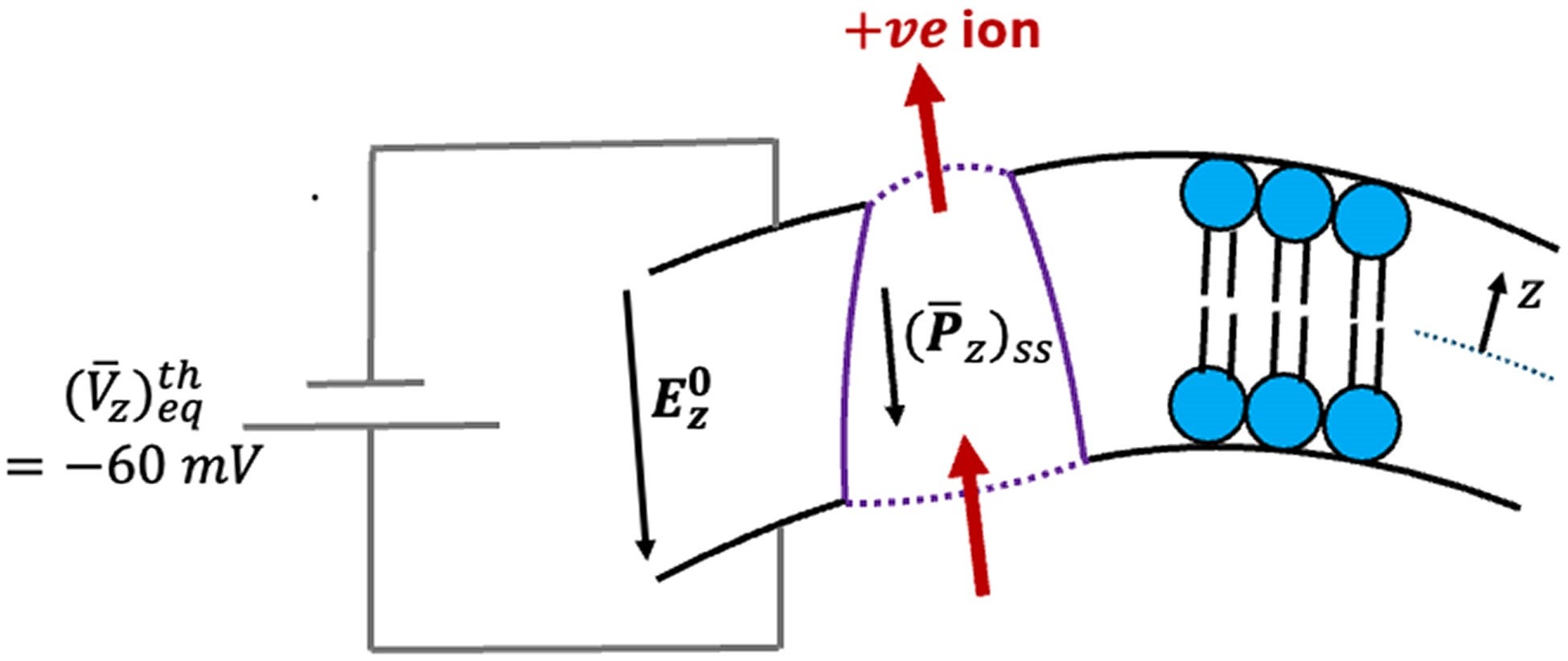

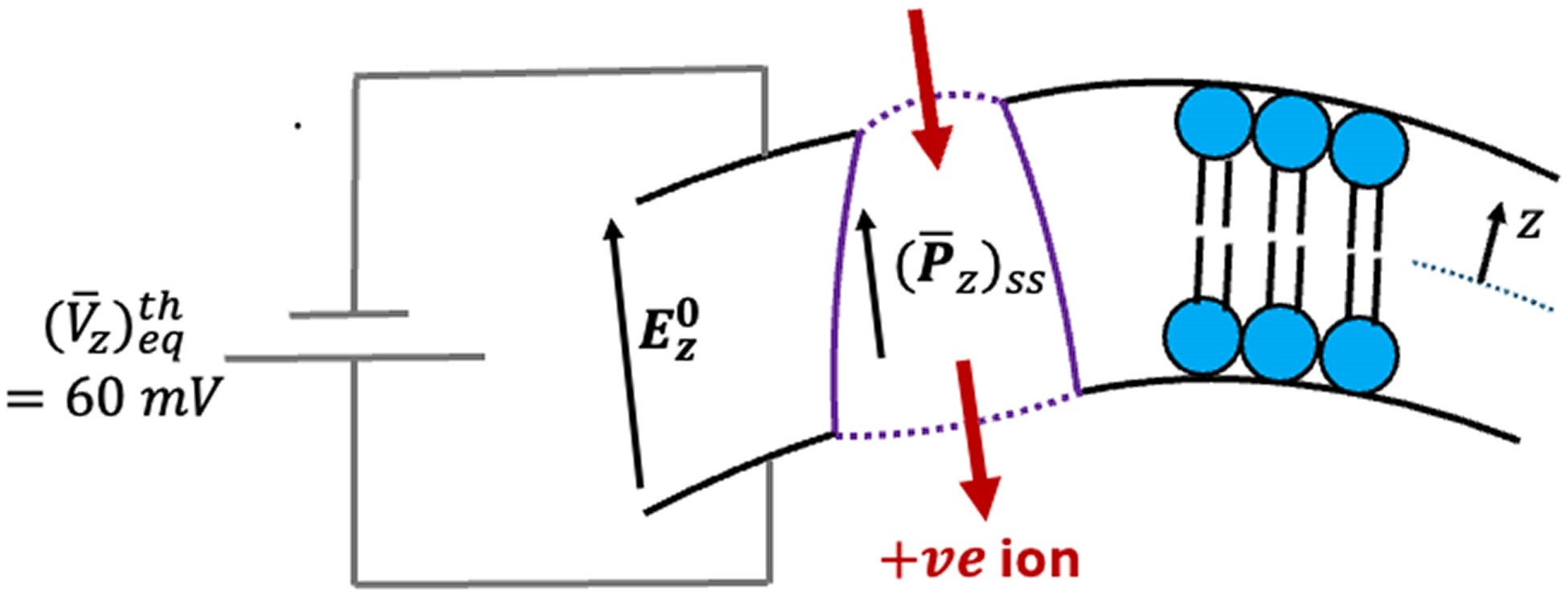

The most striking result comes from linking membrane polarization to voltage across the membrane. Under typical conditions, cells maintain a resting voltage of about minus 60 millivolts. The model predicts that active membrane motion could shift this voltage by as much as 90 millivolts.

That change unfolds over milliseconds, matching the timescale of nerve signals. The predicted voltage rise even resembles the charging curve seen during a neuron’s action potential, though the researchers stress this is a motivating comparison, not a claim that the mechanism replaces known ion channel dynamics.

“Our results reveal that activity can significantly amplify transmembrane voltage and polarization, suggesting a physical mechanism for energy harvesting and directed ion transport in living cells,” the researchers write.

Such voltages are large enough to influence how ions move. Ions are charged atoms, and their movement underlies nerve impulses, muscle contraction, and many other biological processes.

Beyond voltage generation, the model offers a possible way to explain active ion pumping. In cells, ions often move against their natural gradients, a process that requires energy.

The study suggests that changes in membrane polarization inside ion-transporting proteins could bias ion motion. Depending on the existing voltage across the membrane, active motion could either increase or decrease local polarization. In both cases, the effect can push positive ions in a direction that opposes the resting voltage.

This means mechanical activity inside the membrane could help drive ion transport, using energy harvested from internal motion rather than relying solely on chemical reactions.

The direction of this pumping depends on several factors, including membrane elasticity, dielectric properties, protein structure, and the state of the cell. The researchers emphasize that this complexity reflects real biology, where many variables shape cellular behavior.

The implications may extend beyond individual cells. If many membranes fluctuate in coordinated ways, their electrical effects could add up. This idea could help explain how tissues generate large-scale electrical patterns involved in development, healing, and communication between cells.

The study also highlights an important feature of living systems. Even though the basic flexoelectric coupling is linear, the presence of active motion makes the overall response nonlinear. That nonlinearity allows threshold-like behavior, where small changes lead to large effects, a hallmark of biological signaling.

The authors suggest that future work could test these predictions in real cells and explore how electromechanical effects operate in networks of neurons.

“Investigating electromechanical dynamics in neuron networks may bridge molecular flexoelectricity and complex information processing, with implications for both understanding brain function and discovering bio-inspired computational materials,” they write.

This research offers a new way to think about how cells generate and use energy. By showing that membrane motion can produce meaningful electrical signals, it adds a physical layer to existing biochemical models. For researchers, it opens new questions about how mechanics, electricity, and chemistry work together in living systems.

In the long term, the findings could influence medicine and technology. Understanding membrane-based energy conversion may shed light on neurological disorders, hearing loss, or muscle diseases where electrical signaling goes wrong.

Beyond biology, the principles could inspire new synthetic materials or computing systems that mimic how living cells process information using motion and electricity together.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists may have discovered a usable source of electrical power within cells appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.