Concern about insect losses has grown steadily, but most evidence comes from small studies focused on certain species or places. That makes it hard to understand what is happening at larger scales. A new study set out to answer that question in an unusual way. Instead of nets or traps, the team used weather surveillance radar to track insects flying high above the ground across the entire contiguous United States.

The work was led by Elske Tielens at the Swiss Research Institute, alongside Jeff Kelly at the University of Oklahoma and Phil Stepanian, who worked at Oklahoma during the study and is now at MIT Lincoln Laboratory. By analyzing radar data from 140 stations, the researchers created the first continental-scale time series of flying insect abundance in the United States. Their findings were published in the journal Global Change Biology.

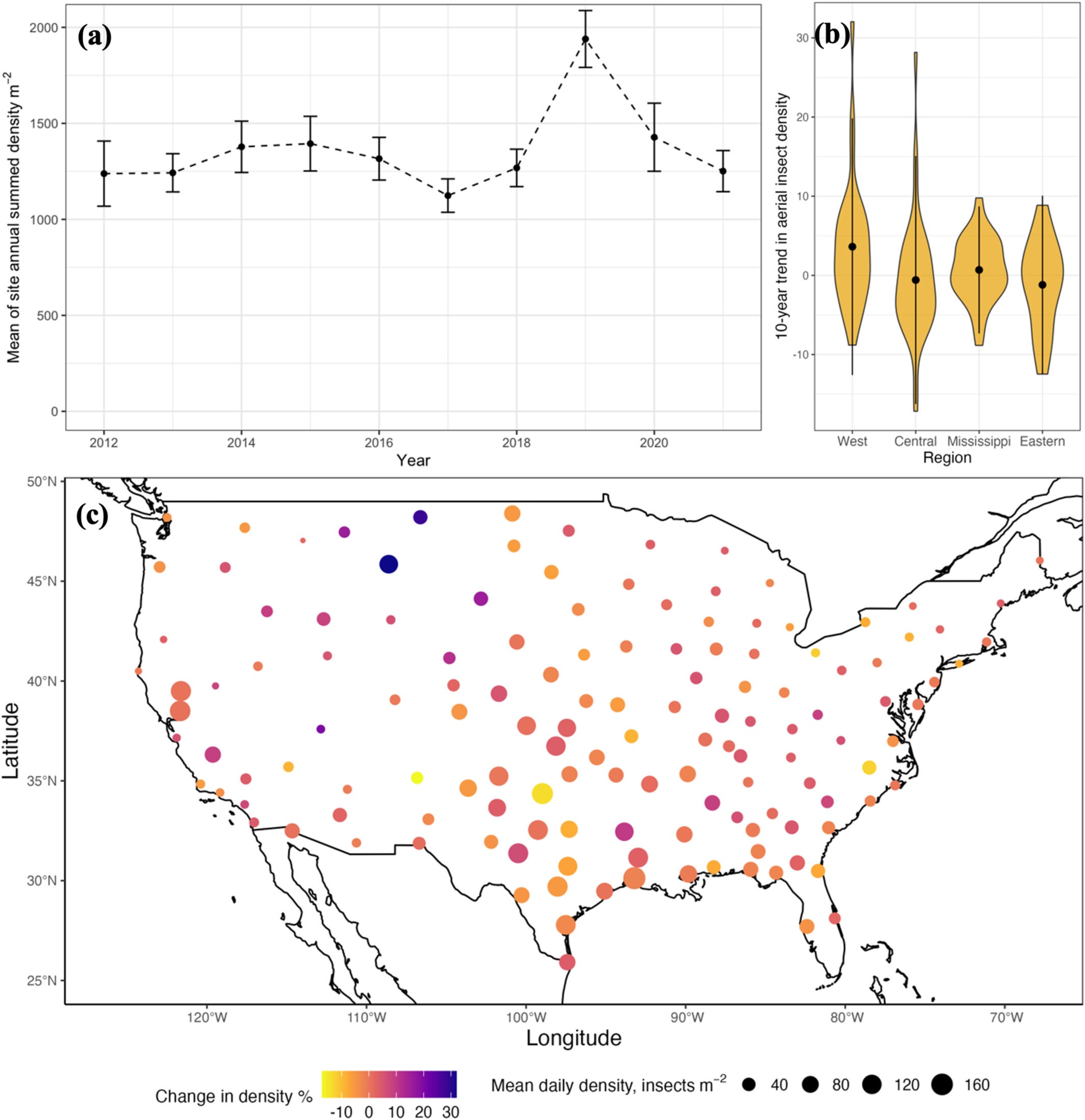

Rather than revealing a nationwide collapse, the results show that overall numbers of day-flying insects in the air remained broadly stable between 2012 and 2021. That stability, however, masks sharp regional differences, with some areas gaining insects and others losing them.

Weather radars are designed to track storms, not animals. Yet anything flying through the air can reflect radar signals. The researchers used data from the U.S. NEXRAD network, which provides high-resolution Doppler radar coverage across the country. They focused only on years when each radar had dual-polarization upgrades, which allow scientists to tell apart different types of objects in the air.

“To avoid confusion with buildings or terrain, our team first identified and removed permanent ground signals. We analyzed radar scans from early January, when insect activity was minimal, and flagged pixels that consistently reflected signals as fixed features. Those areas were then masked from the full dataset,” Kelly explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“Next came the challenge of separating insects from rain and birds. Dual-polarization radar provided several measurements that described shape and orientation. By combining these variables, we filtered out weather signals and excluded returns that matched the size and flight patterns of birds. What remained were signals most consistent with insects,” he continued.

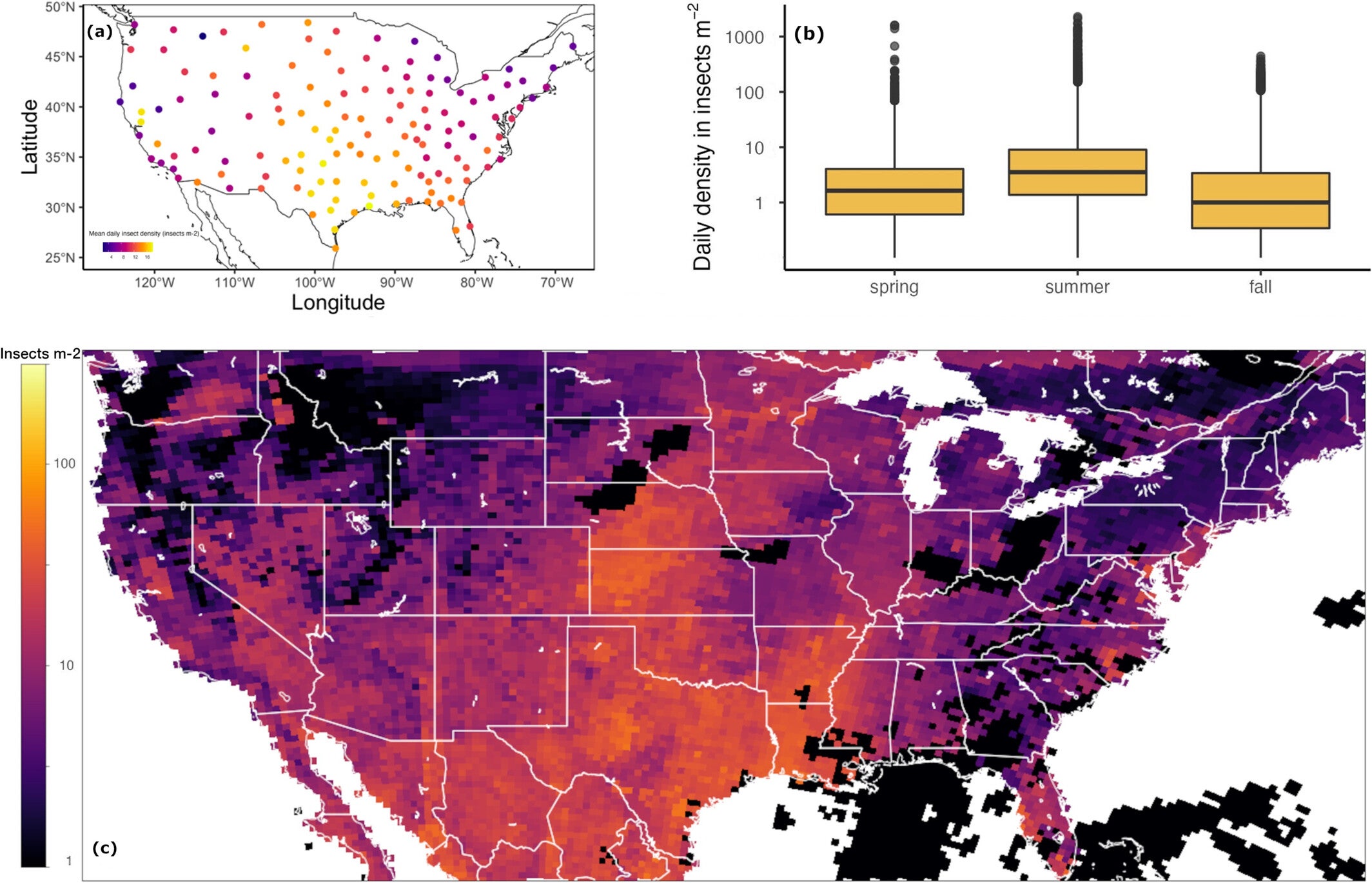

The radar reflectivity data were then converted into estimates of insect density. By assuming an average radar cross section typical of small day-flying insects, the team calculated how many insects occupied a column of air up to three kilometers high above each radar site. On average, about 4.3 insects occupied each square meter of that air column at midday.

Insects were most abundant during summer, with lower numbers in spring and fall. Densities were highest near the Gulf Coast and declined toward northern latitudes. Using weather data to scale these observations, the researchers estimated that on a typical summer day roughly 100 trillion insects fly above the contiguous United States.

When the data were combined across all sites, the trend over the decade showed no clear increase or decrease. Year-to-year variation was strong, but the overall line stayed flat. That finding contrasts with many local studies reporting steep insect losses, and it highlights how scale matters.

Looking site by site, the picture became more complex. About 52 percent of radar locations showed rising insect density over the decade, while 48 percent showed declines. Gains were more common in parts of the northern Plains and the western United States. Losses appeared more often near the coasts. No simple geographic rule explained the pattern.

The team also examined how climate influenced yearly ups and downs. Insect numbers tended to be higher after wetter springs and warmer summers. In contrast, warmer winters in the previous year were linked to lower insect densities. Summer warmth and spring rain boosted insect activity, but mild winters appeared to work against it.

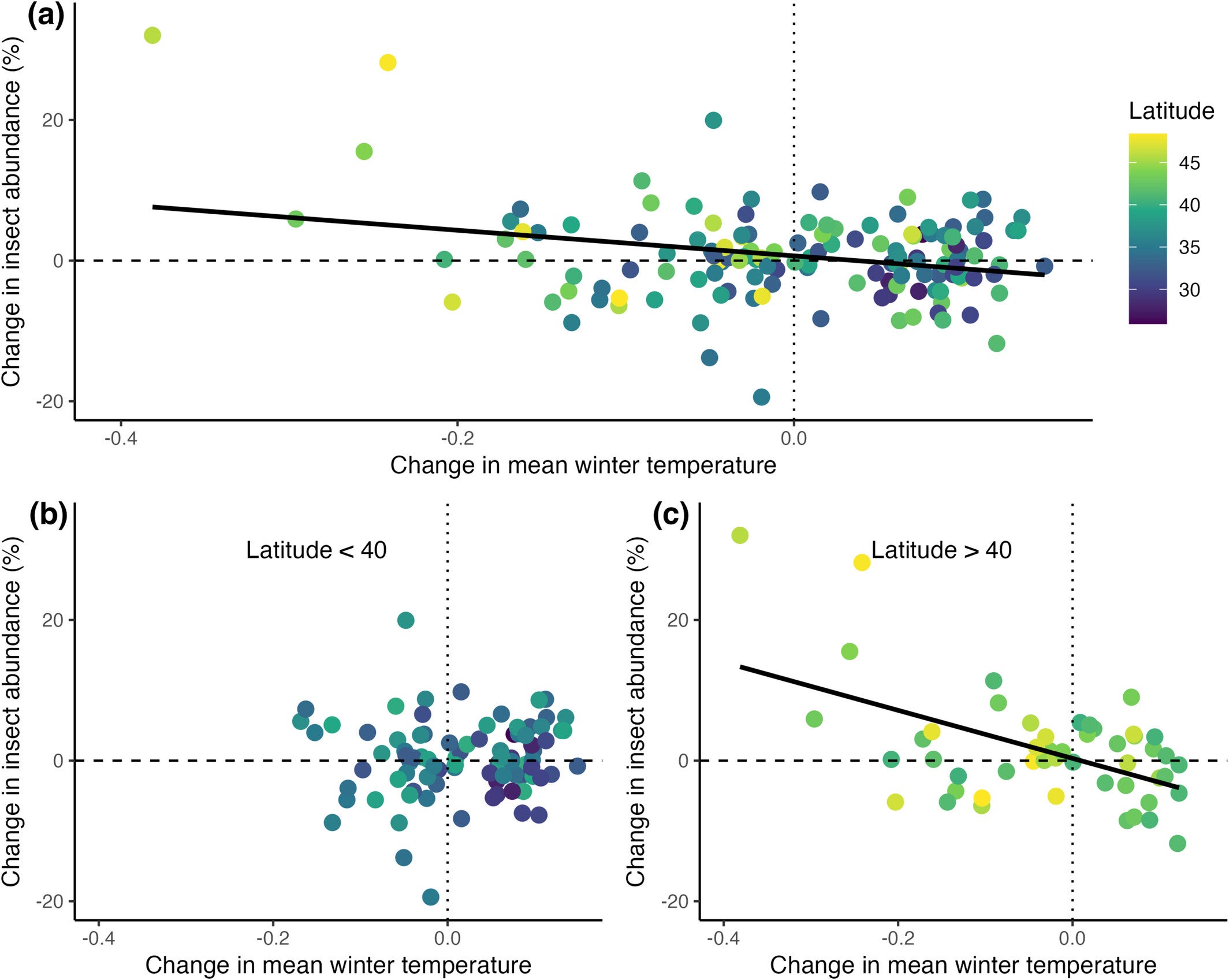

Long-term trends pointed to winter temperature as a key factor. Sites that experienced stronger winter warming over the decade were more likely to show declines in flying insects. This effect was especially clear at higher latitudes, above about 40 degrees north. In those regions, warming winters coincided with sharper drops in insect density.

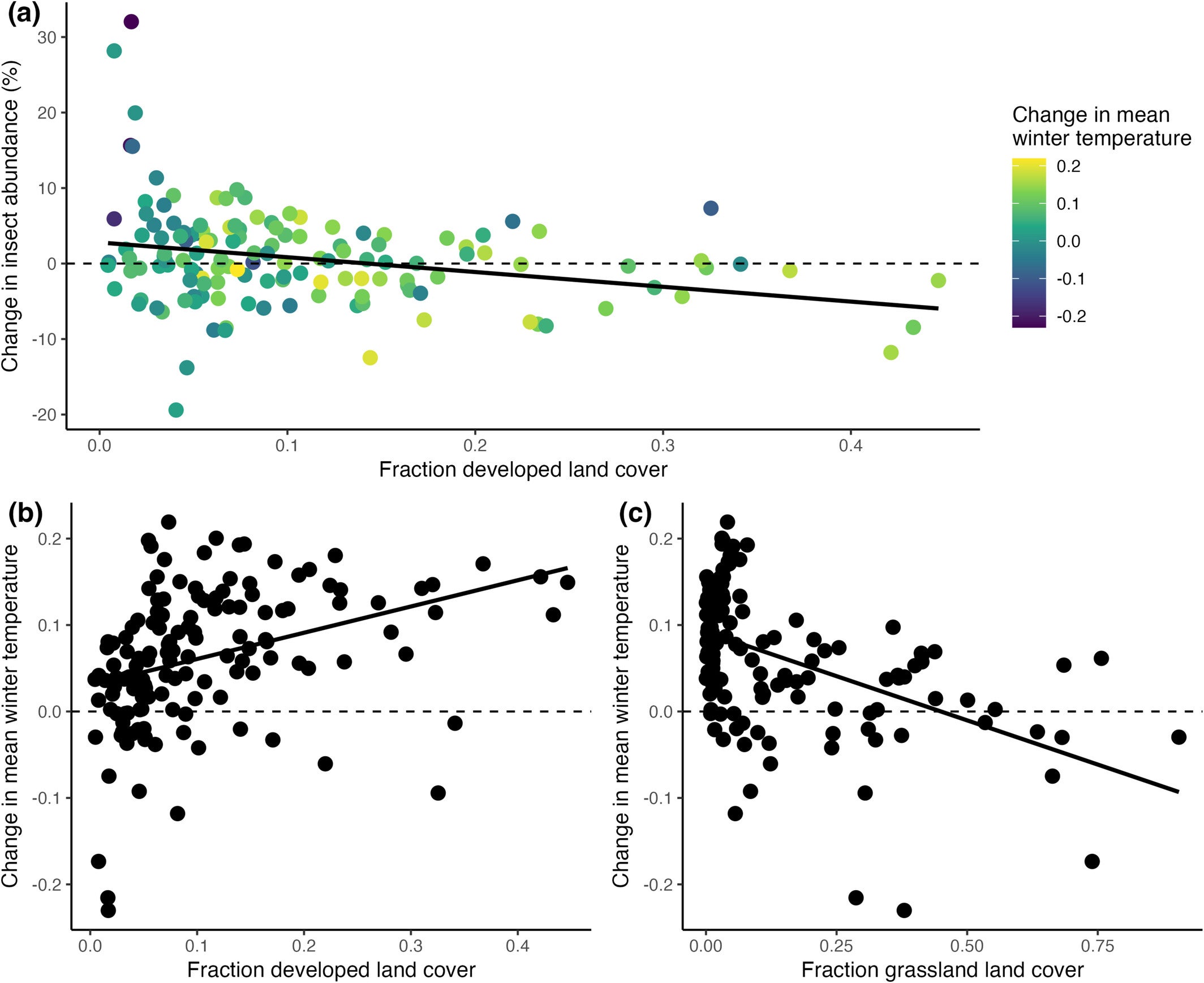

Land use also mattered. Radar sites surrounded by more developed land showed steeper declines over time. Urban and suburban areas tended to warm more in winter, reflecting heat island effects. Grassland-dominated regions often showed weaker warming and more stable insect numbers.

Importantly, winter warming and development each played a role even when accounting for the other. This suggests that rising winter temperatures and human land use place separate pressures on insect populations.

The apparent national stability may seem surprising given widespread concern about insect declines. One explanation is that local losses are being offset by gains elsewhere. Different species and communities respond in different ways, and their changes are not synchronized across the landscape.

The insects detected by radar represent a broad mix, from aphids and thrips to hoverflies, wasps, dragonflies, and some butterflies. Many groups are included, even though individual species cannot be identified. Because of this diversity, radar trends likely reflect broad patterns in insect abundance, not just a few species.

Another reason for caution is timing. The radar record begins in 2012, long after major land-use changes and climate shifts began. “It is likely that the most severe decline in insect populations already took place between the 1970s and 1990s, i.e., before our archived data,” Tielens said. A flat line today does not rule out large losses in earlier decades.

Radar also cannot detect which species are declining. Sensitive insects may be disappearing while more common or adaptable ones increase. “It is therefore important to combine radar data with other data sources; local surveys, citizen science, and so on,” Tielens said.

This study shows that existing weather radar networks can double as powerful tools for tracking insect populations. Because these systems already operate continuously, they offer a low-cost way to monitor insects at continental scales. Extending analyses to older radar archives could reveal longer-term trends and help identify when major changes occurred.

For people, this matters because insects support pollination, pest control, and healthy ecosystems. Early warning of regional declines could guide conservation and land-use decisions before losses become severe. In parts of the world where insect surveys are rare, radar could help fill major data gaps.

By combining aerial monitoring with ground-based studies, scientists can build a clearer picture of how insects respond to climate change and human pressure, and how best to protect them.

Research findings are available online in the journal Global Change Biology.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists reveal the staggering number of insects flying in the sky above the US appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.