Electronics keep shrinking, but silicon is starting to run into physical limits. To go smaller, researchers are turning to something far tinier than any transistor on a chip: single molecules that act as circuit elements in their own right. One of the biggest roadblocks has been surprisingly simple to state and very hard to solve. How do you make a clean, stable electrical connection between a single molecule and metal electrodes so those tiny parts can work together as a real circuit for you to use?

A team in Japan has now taken a major step toward that goal. Researchers at the Institute of Science Tokyo and partner institutes have built silver based atomic switches that can reliably connect individual molecules to electrodes in a solid device. Their work shows how to build and break metal filaments one atom thick, then let a single molecule slip into that gap and carry current.

This sounds abstract, but the goal is concrete. If engineers can wire up molecules in a repeatable way, future circuits could be incredibly compact and sip tiny amounts of energy. You could hold devices in your hand that pack far more computing power than today’s chips, while using less power and generating less heat.

Associate Professor Satoshi Kaneko puts it simply. “The utilization of AS enables stable molecular wiring within a solid-state environment, allowing voltage to be applied directly to functional molecules.” That shift moves molecular electronics from delicate lab tricks toward genuine technology that could one day end up in devices you rely on.

Traditional molecular junction experiments often use mechanical break junctions. In those setups, researchers physically bend or pull a metal wire until it thins to a narrow neck, then snaps. If a molecule happens to bridge the gap, a junction forms. That method is powerful, but it is slow, fragile, and hard to scale up. It is not something you can build into a commercial chip with millions of elements.

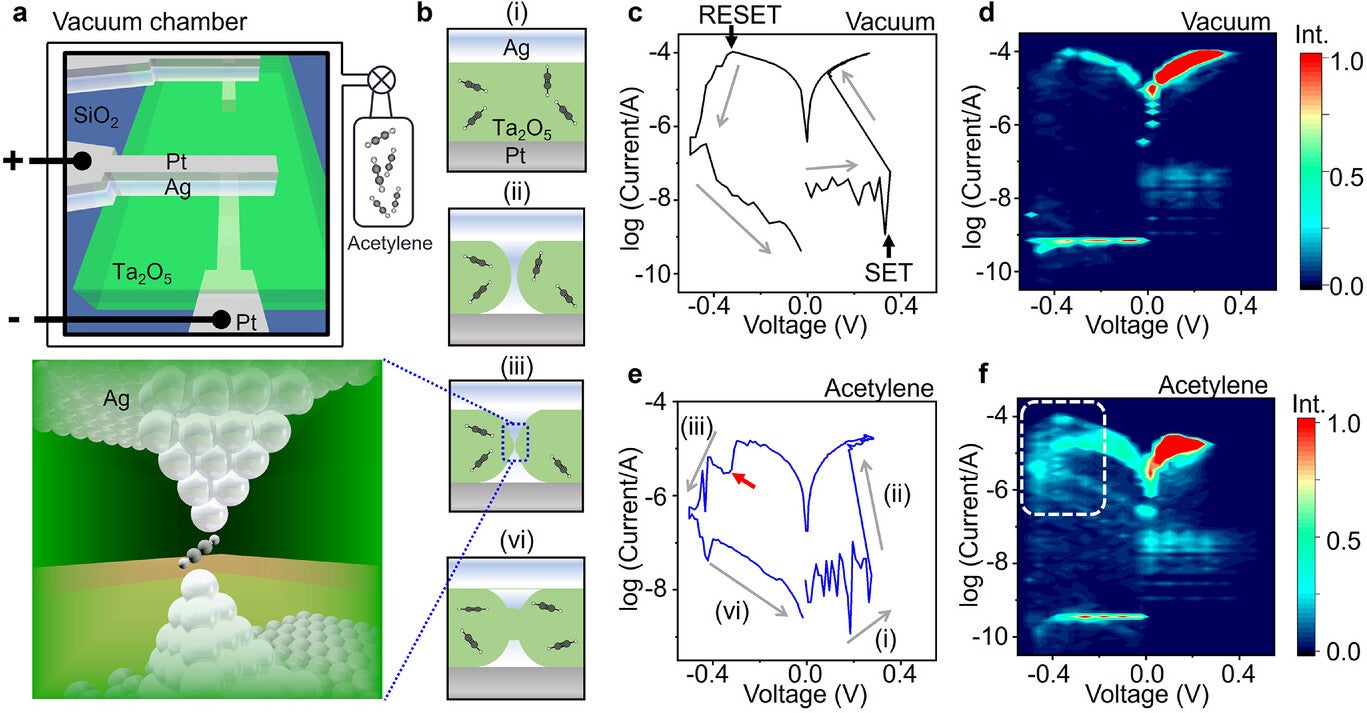

The Japanese team chose a different route. They built an atomic switch on a thin layer of tantalum oxide, known as Ta₂O₅. On one side sits silver, on the other side a counter electrode. When they apply a small positive voltage, around 0.3 volts, silver atoms move through the oxide and line up into a tiny filament that links the two electrodes. Current flows and the switch turns “on.”

Reverse the voltage and the filament dissolves back into ions. The connection breaks, and the switch turns “off.” That cycle of growth and rupture repeats reliably at very low voltages under ultra high vacuum and also in the presence of gas.

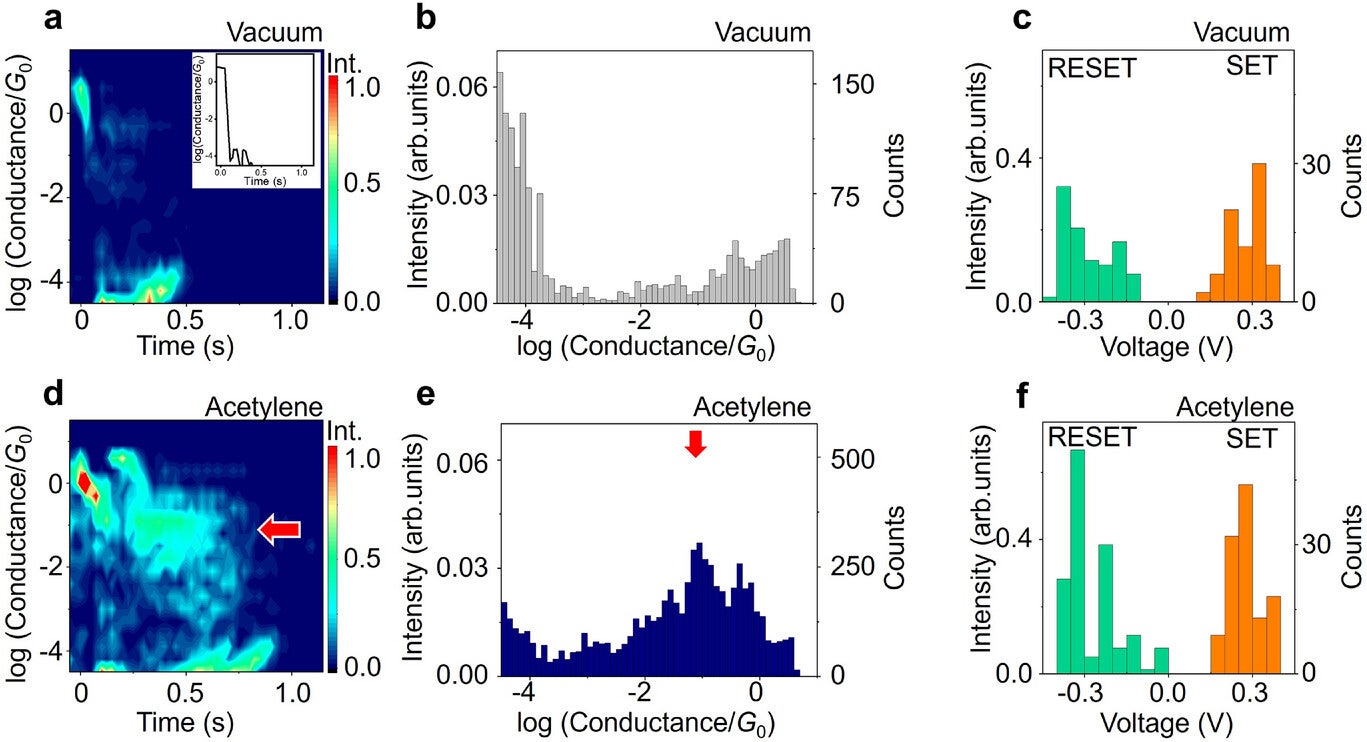

The key twist comes when the researchers introduce acetylene gas. As the silver filament breaks, an acetylene molecule can become trapped between the last silver atoms at each side. In that moment, the molecule itself bridges the gap and becomes the conductor. The device is no longer just a metal filament switch. It has turned into a single molecule junction that can join one molecular component to another.

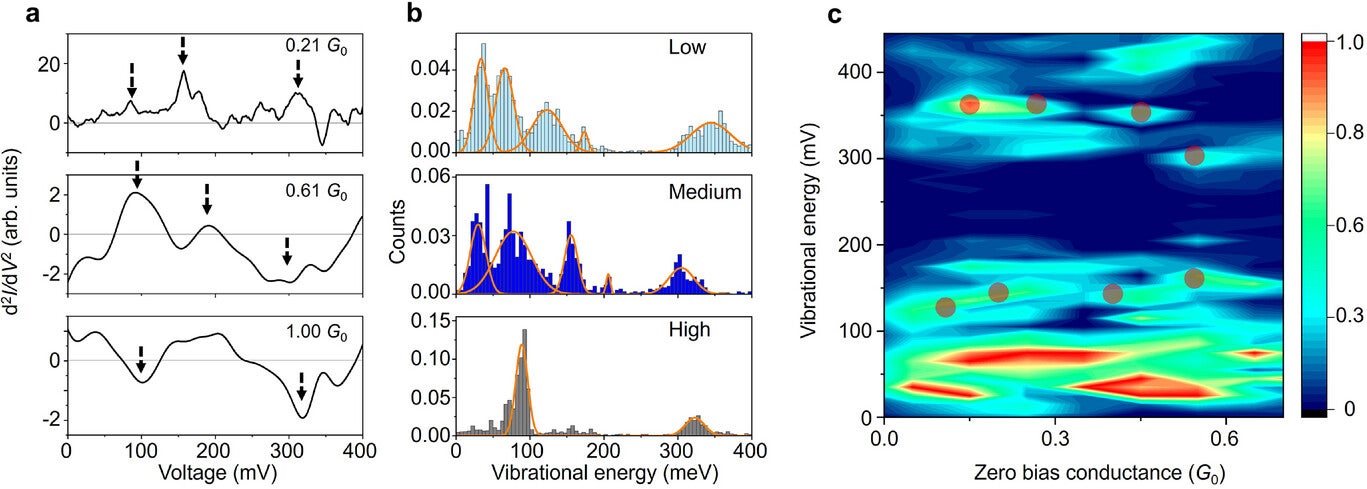

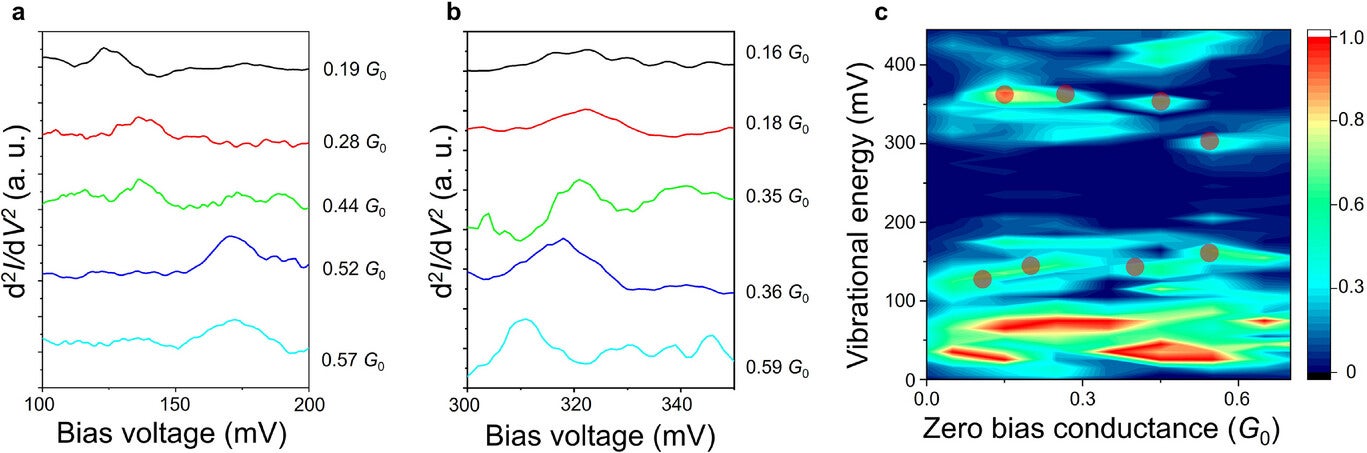

To confirm that acetylene really sat in the middle and carried current, the team relied on a powerful tool called inelastic electron tunneling spectroscopy. In simple terms, this method listens to how molecules vibrate when electrons pass through them. Each molecule has a unique set of vibrational “notes.” When those notes appear in the electrical signal, you know the molecule is part of the current path.

The acetylene molecules in the device produced clear vibrational fingerprints. That proved they were attached directly to the silver filament and helping to carry charge. Without acetylene in the chamber, those signals disappeared.

The researchers also looked at how easily current flowed, a property called conductance. They found values between 10⁻³ and 10⁻¹ times G₀, where G₀ is the fundamental quantum of conductance. That range is typical for single molecule junctions and shows that the connection forms at the scale of just one or a few molecules, not a larger clump of material.

For you, that level of control means these are not vague nanoscale blobs. They are well defined electrical elements, much closer to the robust building blocks needed for real molecular circuits.

One of the most important parts of this work is what the researchers did not have to do. They did not need to move or bend electrodes with nanometer precision in order to form each junction. The atomic switch grows and erases the silver filament under purely electrical control. Molecules slip into place during the normal operation of the switch.

That change has big consequences for scale. Because the process relies on voltage rather than mechanical motion, many switches could operate at once on the same chip. Multiple molecular junctions could form automatically and in parallel. As Kaneko notes, the approach “eliminates the need for mechanical manipulation of electrodes, simplifying device design and enabling parallelization and integration.”

The low operating voltage, around 0.3 volts, also matters. It keeps energy use down and reduces heat, which is crucial if hundreds of thousands of these elements ever run inside a compact device that you carry or wear.

There are still limits. In the current study, the team focused on one molecule, acetylene, and one metal, silver. The junctions stayed stable for fractions of a second, long enough to study them, but not yet long enough for long lived memory or logic devices. Even so, this is a strong proof of concept that atomic switch based molecular wiring can work under solid state conditions.

“In the long term, this research could reshape how electronic hardware is built and how it feels to use. Circuits made from molecules rather than silicon transistors could reach far higher densities. That would let designers pack more memory and logic into a much smaller space. Your future phone, watch, or medical implant might run longer on a single charge and stay cooler, because each operation would use less energy,” Kaneko told The Brighter Side of News.

Molecular junctions also naturally display quantum effects, such as conductance quantization and energy dependent transport. Engineers could harness these features to make ultra sensitive chemical or biological sensors. A device might detect a single molecule of a toxin or a biomarker for disease and convert that event into a clear electrical signal.

Because the atomic switch approach allows many junctions to form at once, it could accelerate research on molecular logic, neuromorphic computing, and new types of memory that blur the line between storage and processing. That shift would change not only how fast devices respond, but how they learn and adapt.

Finally, the method points to more sustainable electronics. Smaller elements that run at lower voltages and use less material can cut energy demand and reduce waste. Over time, that can benefit both human health and the environment that supports every device you use.

Research findings are available online in the journal Small.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists use atomic switches to reliably connect individual molecules to electrodes appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.