Morning routines can feel small until you picture what happens right after breakfast. Sugar hits your mouth. Bacteria in plaque go to work. They ferment those sugars and release acids that soften enamel. If those acid attacks repeat, cavities follow.

A clinical trial from Aarhus University in Denmark suggests a simple helper already present in your body may blunt that acid drop. The helper is arginine, an amino acid found in saliva. In the study, arginine made dental biofilms less acidic after sugar, shifted their sticky carbohydrate makeup, and slightly reshaped which bacteria thrived.

The work matters because it moves beyond lab dishes. It tests biofilms in real mouths, in people with active tooth decay. It also looks at plaque as it truly exists, layered, uneven, and full of tiny “hot spots” where acids can pool.

Dental caries starts with chemistry. You carry many bacteria in your mouth. When sugars arrive, some bacteria ferment them and generate acids. Those acids lower pH in plaque, and enamel begins to break down.

Plaque is not a smooth film. It is a community called a dental biofilm. It has channels, pockets, and a glue-like matrix that traps acids near the tooth surface.

Arginine has drawn attention for years because some helpful bacteria can break it down through an arginine deiminase system, or ADS. That pathway creates alkali that can neutralize acids. More arginine can support these alkali-producing bacteria. At the same time, it can make life harder for acid-producing bacteria.

Earlier studies outside the mouth suggested arginine could change biofilms. This clinical trial set out to see if that also happens in people.

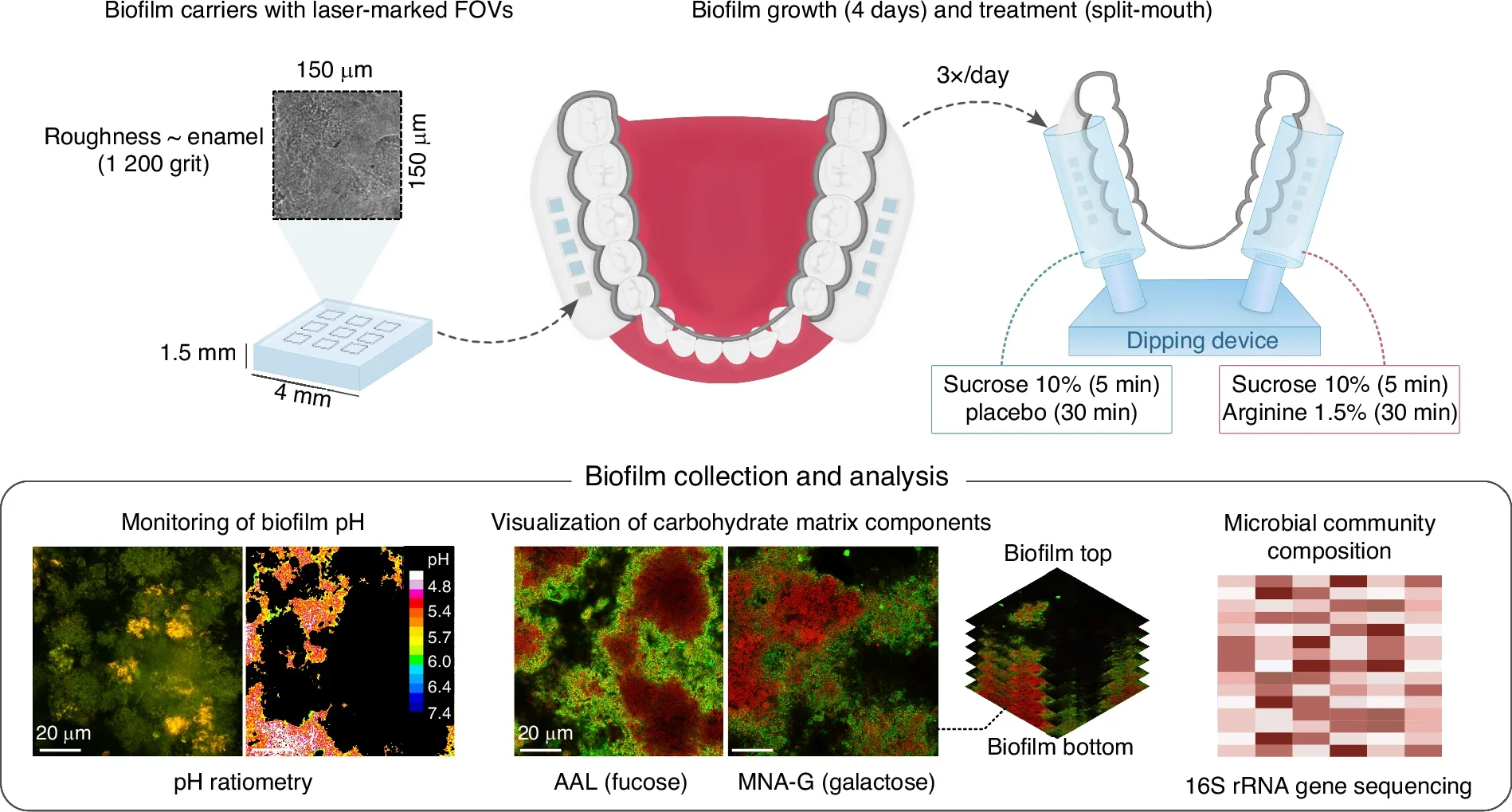

The research team recruited 12 participants with active caries. To collect intact biofilms, the team prepared specialized dentures. These dentures allowed biofilms to grow on both sides of the jaw in a controlled way.

Participants followed a strict routine. Three times a day, they dipped the dentures in a sugar solution for five minutes. Immediately after, they dipped one side in distilled water, used as a placebo, and the other side in arginine for 30 minutes. The arginine always went on the same side for each person.

“The aim was to investigate the impact of arginine treatment on the acidity, type of bacteria, and the carbohydrate matrix of biofilms from patients with active caries,” said Schlafer, a professor at the Department of Dentistry and Oral Health.

After four days of repeated sugar challenges and treatments, the dentures were removed. The biofilms were then analyzed in detail.

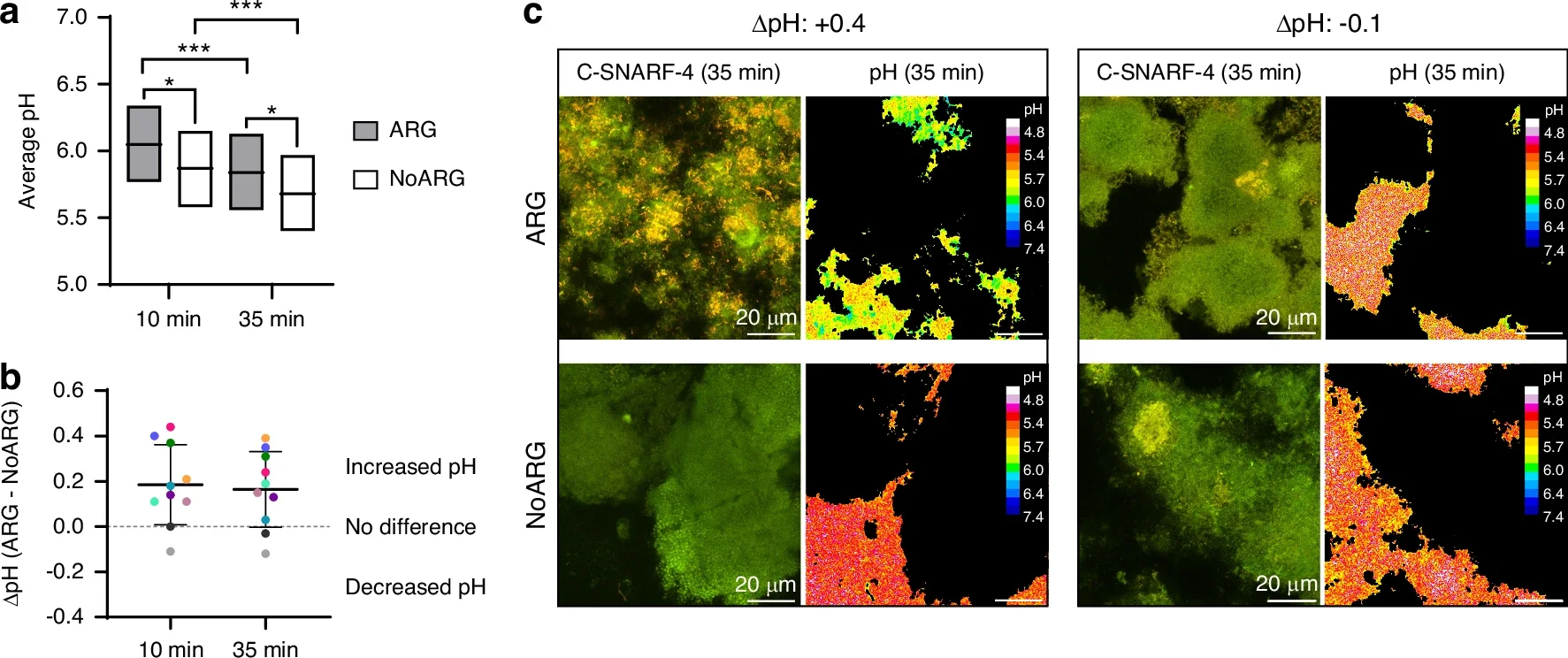

To measure acidity inside the biofilms, researchers used a pH-sensitive dye called C-SNARF-4. This dye lets scientists map pH across different spots in a biofilm instead of relying on one average value.

The results showed a consistent trend. Biofilms treated with arginine kept a significantly higher pH at 10 and 35 minutes after a sugar challenge. Higher pH means lower acidity, which is better for enamel.

“Our results revealed differences in acidity of the biofilms, with the ones treated with arginine being significantly more protected against acidification caused by sugar metabolism,” Del Rey said.

This is the kind of change that matters in daily life. Cavities form when plaque stays acidic long enough and often enough. Even if sugar hits, a faster return toward safer pH can reduce harm.

The mapping also highlighted something you may already suspect from experience. Not every area of plaque behaves the same. Some spots become far more acidic than others, creating small “acidic pockets” that can quietly drive decay.

Plaque bacteria live in a scaffold. That scaffold is a carbohydrate-rich matrix that helps the biofilm cling to surfaces and hold together under chewing and brushing.

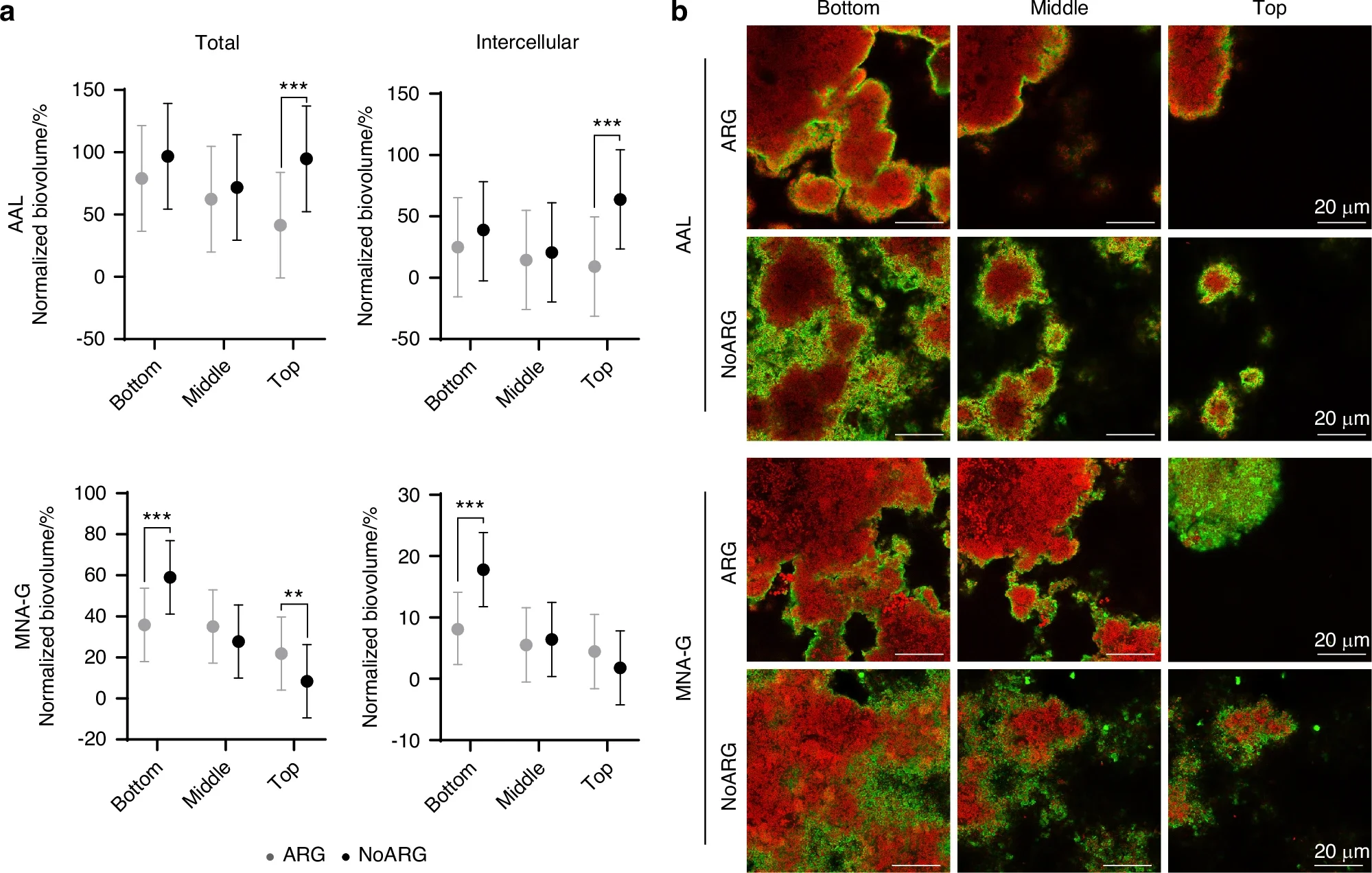

The team stained two common carbohydrate components in the biofilm, fucose and galactose, using carbohydrate-binding proteins called lectins tagged with fluorescent dye. These carbohydrates make up a large portion of dental biofilms and may help create acidic pockets.

With arginine treatment, researchers saw an overall reduction in fucose-based carbohydrates. That shift may make the biofilm less harmful, since the matrix can influence how acids collect and how hard plaque is to disrupt.

The galactose story was more complex. The total amount did not simply drop. Instead, the biofilm’s structure appeared to change. Galactose-containing carbohydrates decreased at the bottom and increased at the top.

That matters because the bottom of the biofilm sits closest to enamel. If the lower layer becomes less supportive of deep acidic pockets, the tooth surface may gain a small but meaningful buffer.

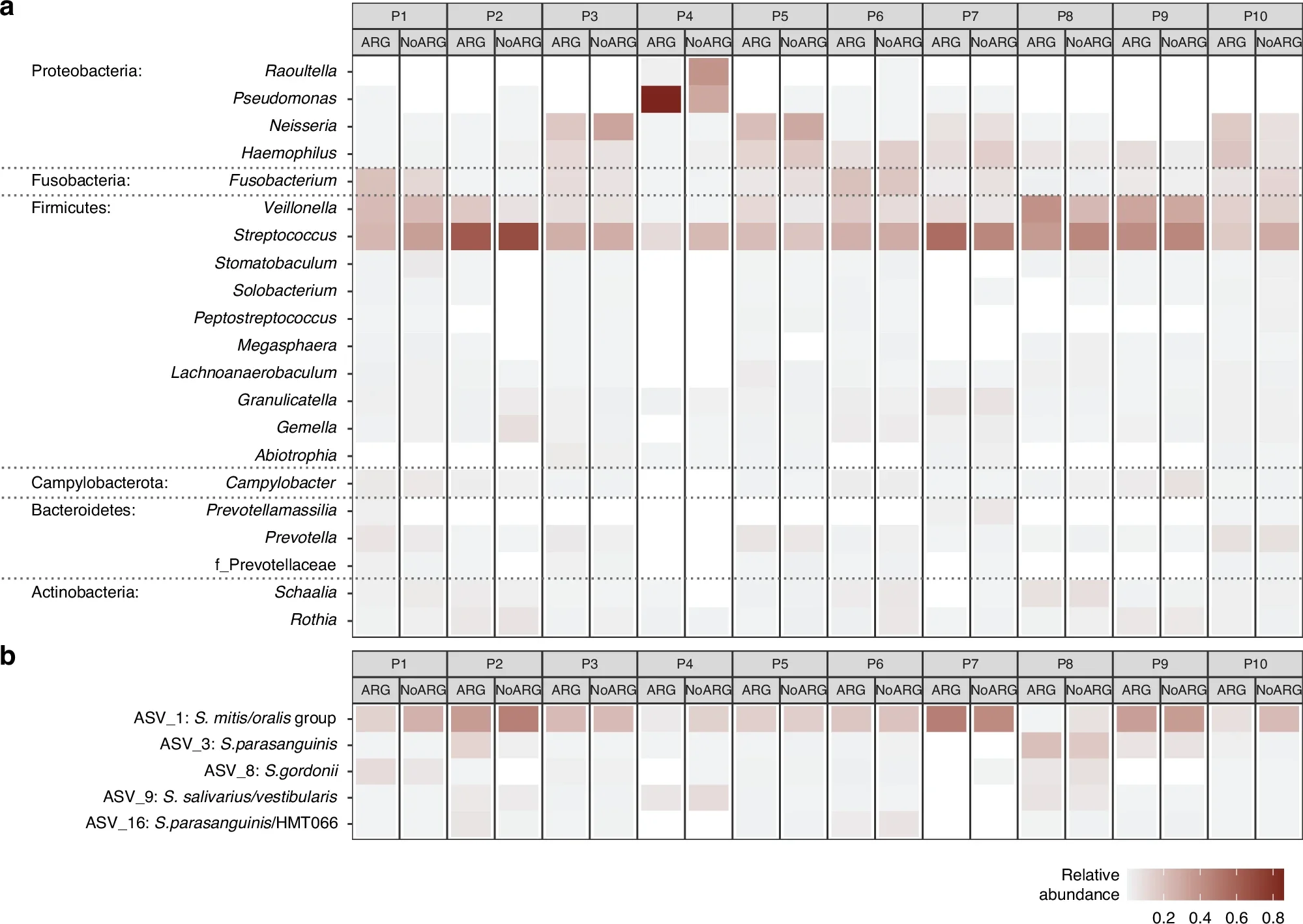

The researchers also looked at which bacteria were present using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, a method that identifies bacteria by reading genetic signatures.

Both arginine-treated and placebo biofilms were dominated by Streptococcus and Veillonella species. That matches what you expect in dental biofilms.

Still, arginine produced important shifts. It significantly reduced the mitis-oralis group of streptococci. These bacteria produce acid but do not strongly produce alkali. The treatment also slightly increased streptococci with considerable arginine metabolism, which can support higher pH.

Put together, the microbial changes match the pH results. Arginine nudged the community toward a less acidic state, without completely rewriting which groups dominate.

The study’s overall message is not that arginine “kills” bad bacteria. It is that it changes the biofilm’s internal economy. More arginine can reward bacteria that neutralize acid. It can also reduce the advantage of bacteria that thrive in low pH.

This trial gives dentists and researchers stronger clinical evidence that arginine can make plaque less damaging after sugar exposure, at least in people with active caries. That matters because sugar-driven acid attacks happen every day, often several times a day. If a safe, naturally occurring amino acid can reduce how sharply plaque acidifies, it could support a more protective oral environment.

The findings also point to new prevention strategies that do not rely only on removing plaque or avoiding sugar. Arginine appears to influence three linked parts of the cavity process: acidity, the biofilm’s carbohydrate scaffold, and the mix of bacteria. That multi-part effect could be helpful for people who remain at higher risk even with good brushing, such as those with frequent snacking, dry mouth, or a history of repeated cavities.

The study also suggests practical product pathways. The authors note that supplementation of arginine in toothpastes or oral rinses could help people more susceptible to caries. Because arginine is naturally produced in the body and present in dietary proteins, it is described as harmless and could even find use in children.

Future research can now focus on dosage, timing, and which patients benefit most, using the same kind of in-mouth biofilm collection methods to test real-world routines.

Research findings are available online in the International Journal of Oral Science.

The original story “Simple amino acid in saliva could help you keep that beautiful smile” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Simple amino acid in saliva could help you keep that beautiful smile appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.