Chronic kidney disease can quietly reshape a life long before the first lab test comes back abnormal. More than 700 million people worldwide live with damaged kidneys, and for many, the risk begins in their DNA long before any symptoms appear.

One gene, called APOL1, has drawn special attention. Certain versions of this gene protect people of West African ancestry from deadly infections like African sleeping sickness. The same variants, however, come with a serious tradeoff.

Two high-risk forms of APOL1 occur in up to 13 percent of people with West African roots, and about 38 percent carry at least one copy. If you inherit both risky versions, your chance of developing severe kidney disease rises sharply. Doctors call this APOL1-mediated kidney disease, or AMKD.

Even with that knowledge, one big question has remained open: how does a small change in APOL1 trigger damage inside the kidney, and why do some people stay healthy for years while others decline quickly?

To answer that, Siebe Spijker and colleagues at Leiden University turned to a surprisingly personal model of the disease. They started with skin samples from people already living with AMKD. From those tiny biopsies, they created induced pluripotent stem cells, a special type of cell that can be reprogrammed to form many tissues.

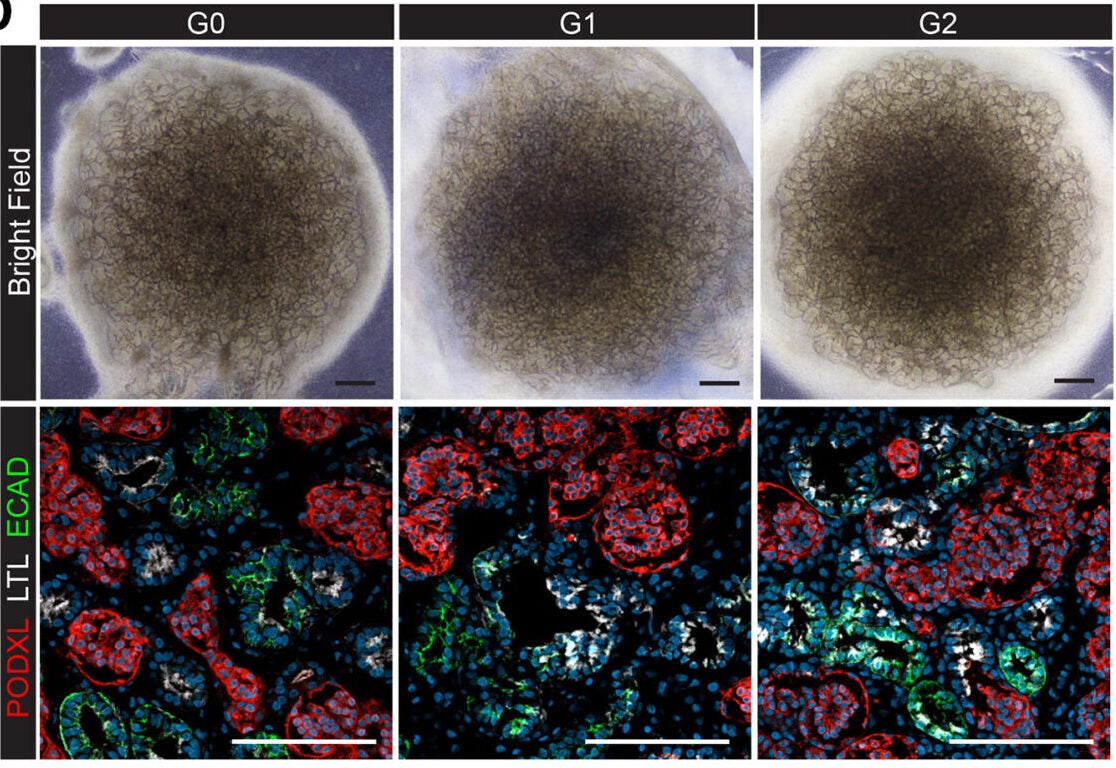

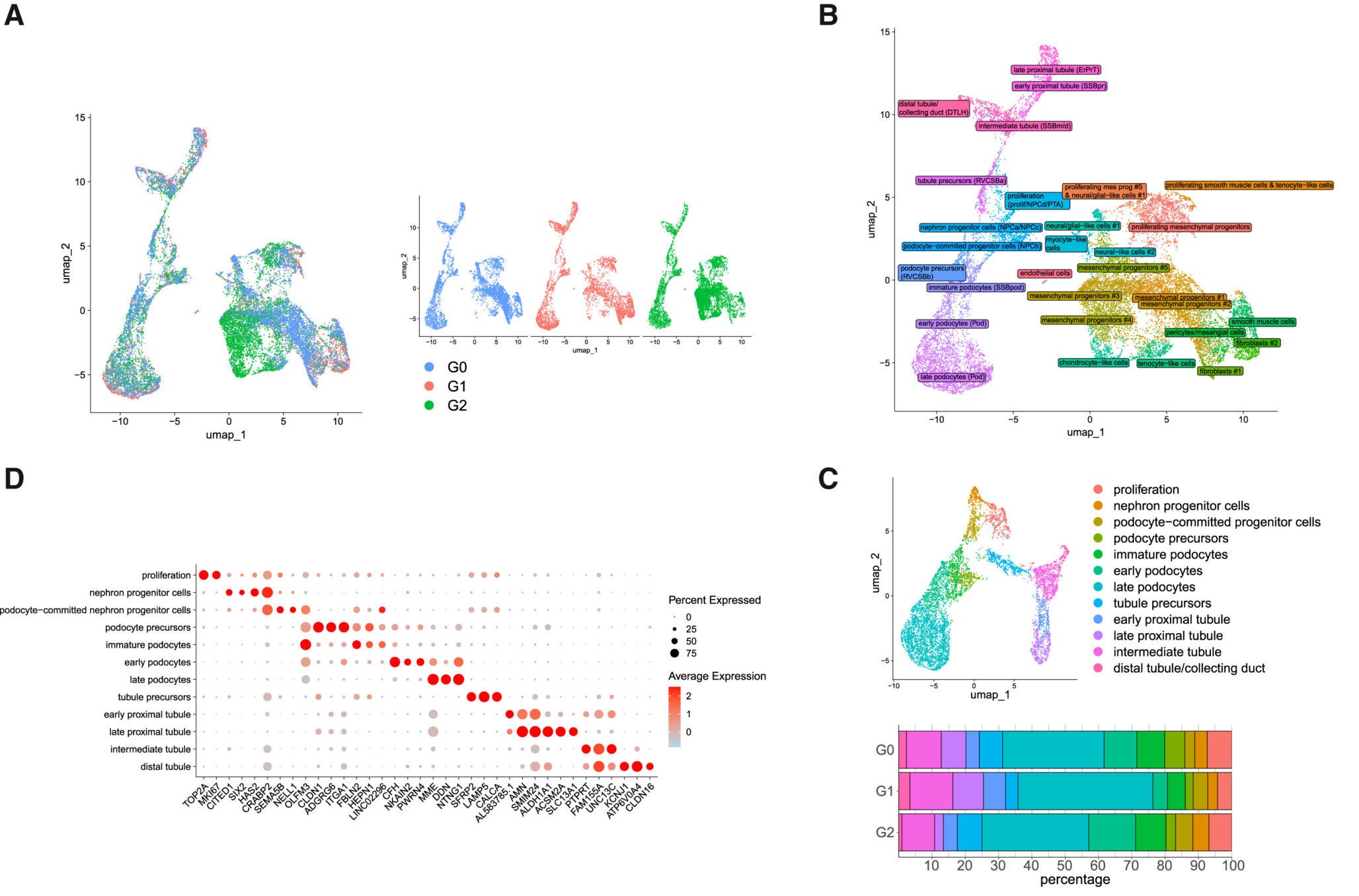

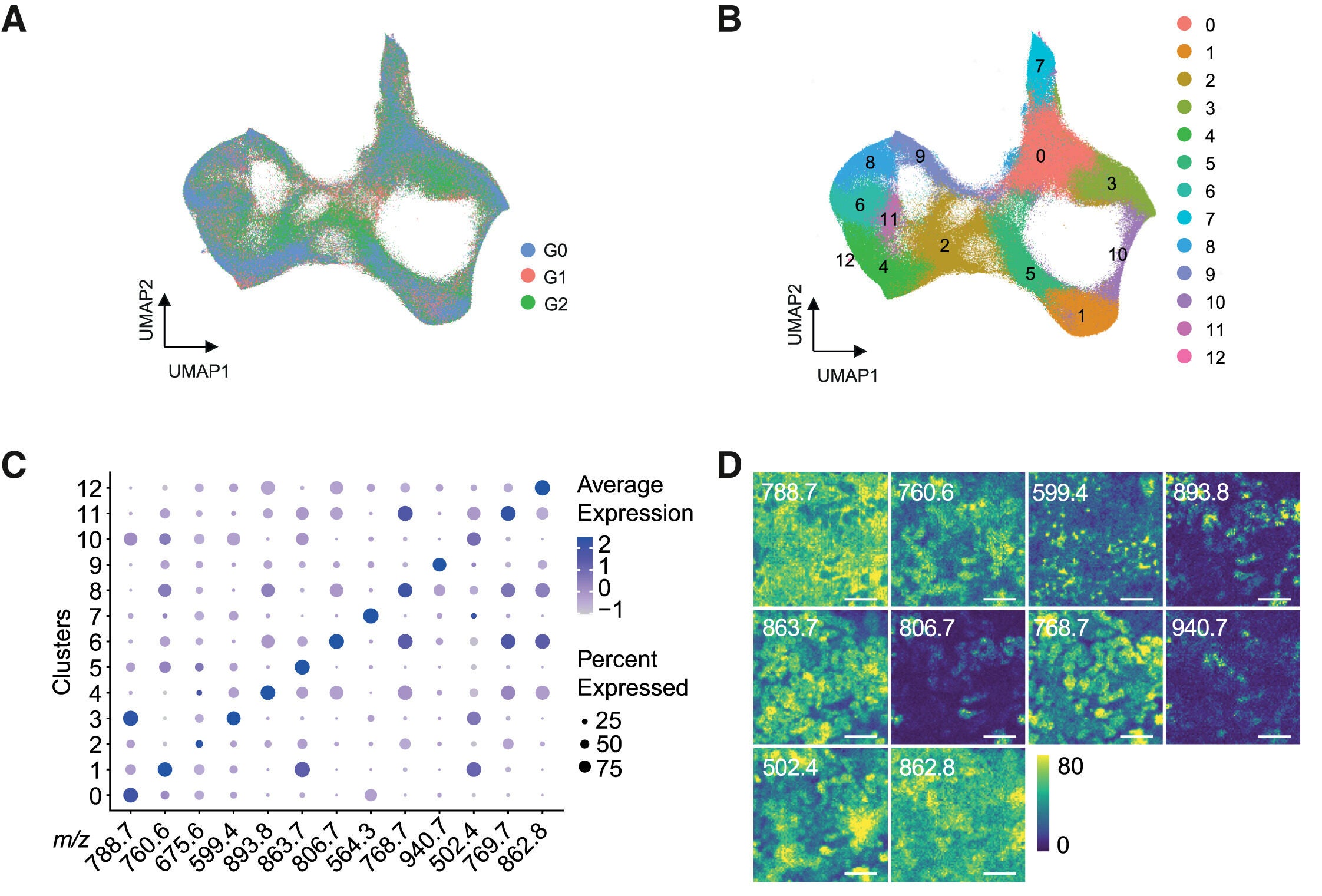

In the lab, the team coaxed those stem cells into forming three-dimensional “kidney organoids,” tiny structures that mimic key parts of a real kidney. These mini organs contained many of the same cell types that sit inside your own filters, including podocytes, the cells that wrap around glomerular capillaries and help separate waste from what your body needs to keep.

To make sure APOL1 itself was the culprit, the researchers used gene editing to correct the risk variants in some of the organoids. That gave them two versions of each mini kidney: one with the original high-risk APOL1, one with the repaired gene. Any differences between the two pointed straight toward the effects of the mutation.

When the team probed these organoids with a battery of tests, a clear pattern emerged. The risky version of APOL1 disrupted mitochondria, the small structures that act as energy factories in your cells. These powerhouses help produce the fuel that keeps each cell alive and working.

Podocytes took the hardest hit. These cells make more APOL1 protein than other cells in the kidney, so any defect in the gene hits them first. In organoids carrying the risk variants, podocytes showed signs that their mitochondria were not working properly. Energy production faltered, and the normal balance of metabolism shifted.

Crucially, those problems became most obvious under stress. When the researchers exposed the organoids to inflammatory molecules, similar to the signals that surge during a viral infection or an autoimmune flare, the damaged mitochondria struggled. Podocytes with mutant APOL1 could not keep up with the energy demand.

That finding fits what many patients experience. People with high-risk APOL1 often stay stable until a major inflammatory event, such as a serious infection, pushes their kidneys past a tipping point. The study suggests that inflammation flips a switch, revealing an energy weakness that had been hiding in their filtering cells.

“Traditional animal models have not been able to fully capture this disease. Rodents do not naturally express APOL1 in their kidneys, so they cannot show the same genetic risk that humans carry. That gap has slowed progress toward real treatments, Spijker told The Brighter Side of News.

“By contrast, the organoids created in Leiden come directly from patients’ own cells. They carry the exact APOL1 variants and the full human genetic background. That makes them a powerful test bed for studying how the disease starts and for trying new drugs,” he continued.

“We anticipate that this human kidney organoid model will advance our understanding of AMKD and accelerate drug discovery, particularly given that APOL1 is not endogenously expressed in rodents,” Spijker said.

Because the team also built “fixed” organoids with corrected APOL1, they can now compare healthy and risky versions side by side in a dish. That setup lets researchers watch how podocytes change over time, how inflammation worsens those changes, and how different treatments might protect the fragile mitochondria inside.

This work paints a sharper picture of AMKD as a disease of energy failure in specific kidney cells. Mutant APOL1 does not simply sit in the background. It pushes podocytes toward a less efficient way of making energy and leaves them vulnerable whenever inflammation rises.

That insight gives drug developers several new options. One path is to design medicines that stabilize mitochondria in podocytes so they can keep producing fuel even when inflammatory signals are high. Another approach is to dampen the harmful response of APOL1 to those signals without blocking its helpful role in fighting infections.

For you, especially if you come from a community where APOL1 risk variants are more common, this research also underscores the importance of preventing and treating serious infections and chronic inflammation. Every avoided inflammatory hit might help protect already stressed filtering cells in your kidneys.

The study, published in Stem Cell Reports, does not offer an immediate cure. It does, however, move the field from broad associations to a concrete mechanism inside real human cells. That kind of detailed understanding is often the first step toward therapies that do more than slow damage and instead go after its root cause.

These findings reshape how scientists and doctors think about APOL1-mediated kidney disease. By showing that mutant APOL1 directly harms mitochondrial function in podocytes, the study identifies energy failure as a central driver of kidney injury in high-risk patients. In practical terms, this means future treatments can focus on stabilizing mitochondria, supporting cellular metabolism, or blocking the harmful response of APOL1 during inflammation.

For researchers, patient-derived kidney organoids now offer a human model that avoids the limits of rodent studies and can be used to screen potential drugs far more quickly. For clinicians, the link between inflammation and mitochondrial stress helps explain why flare-ups of infection or autoimmune disease often precede kidney decline in people with APOL1 variants.

In the long run, combining genetic testing for APOL1 with strategies that limit inflammatory stress and protect podocyte energy supply could delay or prevent kidney failure, improving outcomes for millions of people at risk.

Research findings are available online in the journal Stem Cell Reports.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Single gene reveals why inflammation triggers kidney failure appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.