Climate can change fast, even when the planet looks stable. Earth has flipped into new patterns within decades in the past. During the last Ice Age, Greenland warmed by as much as 16°C over short spans. The North Atlantic also saw repeated iceberg surges. Scientists call these abrupt jumps Dansgaard–Oeschger and Heinrich events.

For years, many researchers tied those rapid swings to ice sheets. That link made sense in an icy world. It also left a major puzzle. How could climate lurch on thousand-year timescales during hot “greenhouse” periods with little or no polar ice?

An international team now offers a strong answer. Professor Chengshan Wang of the China University of Geosciences (Beijing) led the work with collaborators in Belgium, Austria, and China. Paleoclimatologist Michael Wagreich of the University of Vienna was among the co-authors. The group reports that Earth’s orbital wobble; not ice sheets; can trigger millennial-scale climate cycles in an ice-free world. Their study appeared in Nature Communications.

The researchers focused on the Late Cretaceous, about 83 million years ago. That era had high carbon dioxide and no large ice sheets. It offers a clean test of whether fast climate cycles need ice.

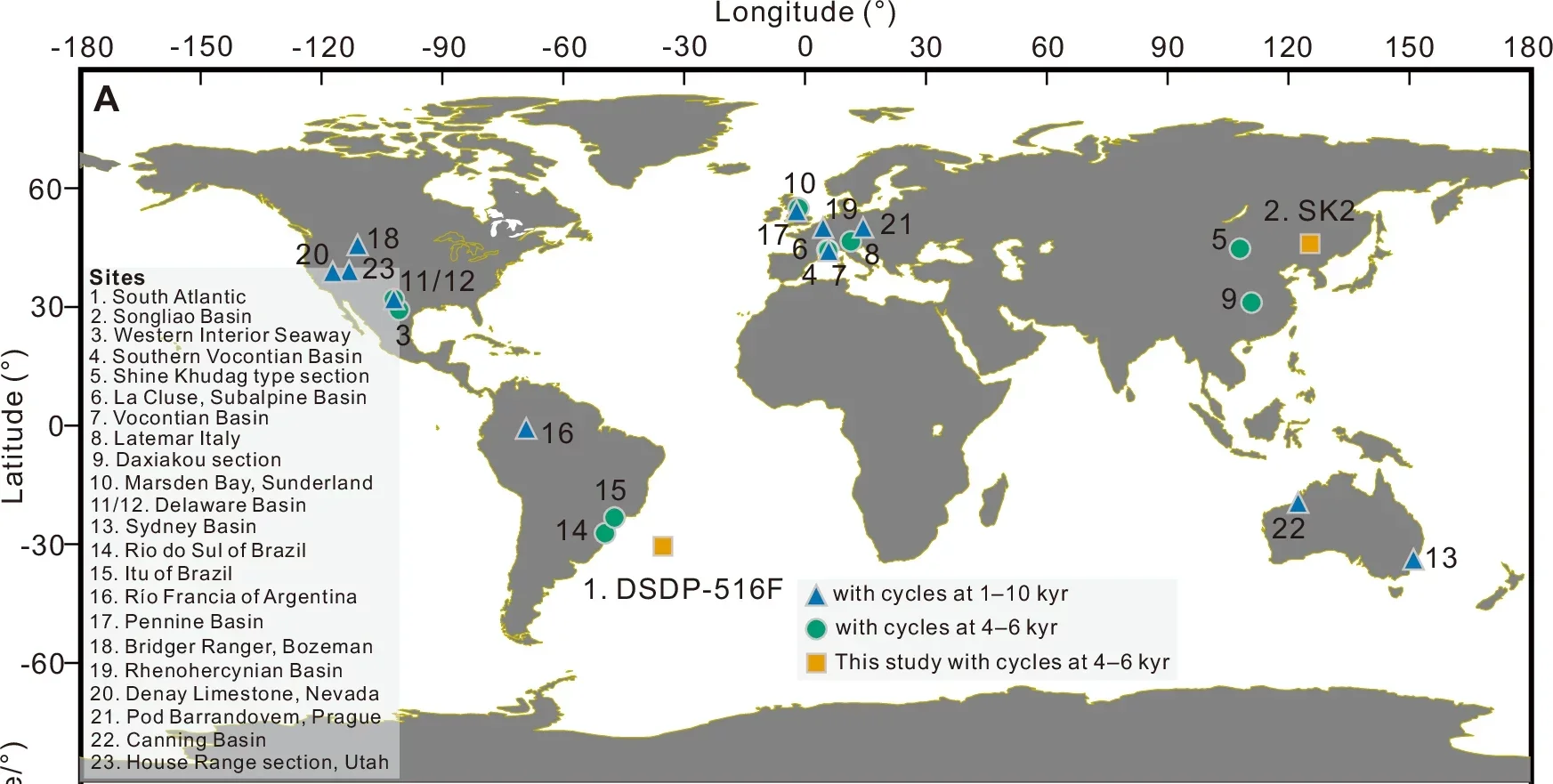

The backbone of the study comes from sediment cores in China’s Songliao Basin. Those rocks formed in a deep lake during the early Campanian stage. The cores were recovered through the Cretaceous Continental Scientific Drilling Project, an international effort launched in 2006 by Wang.

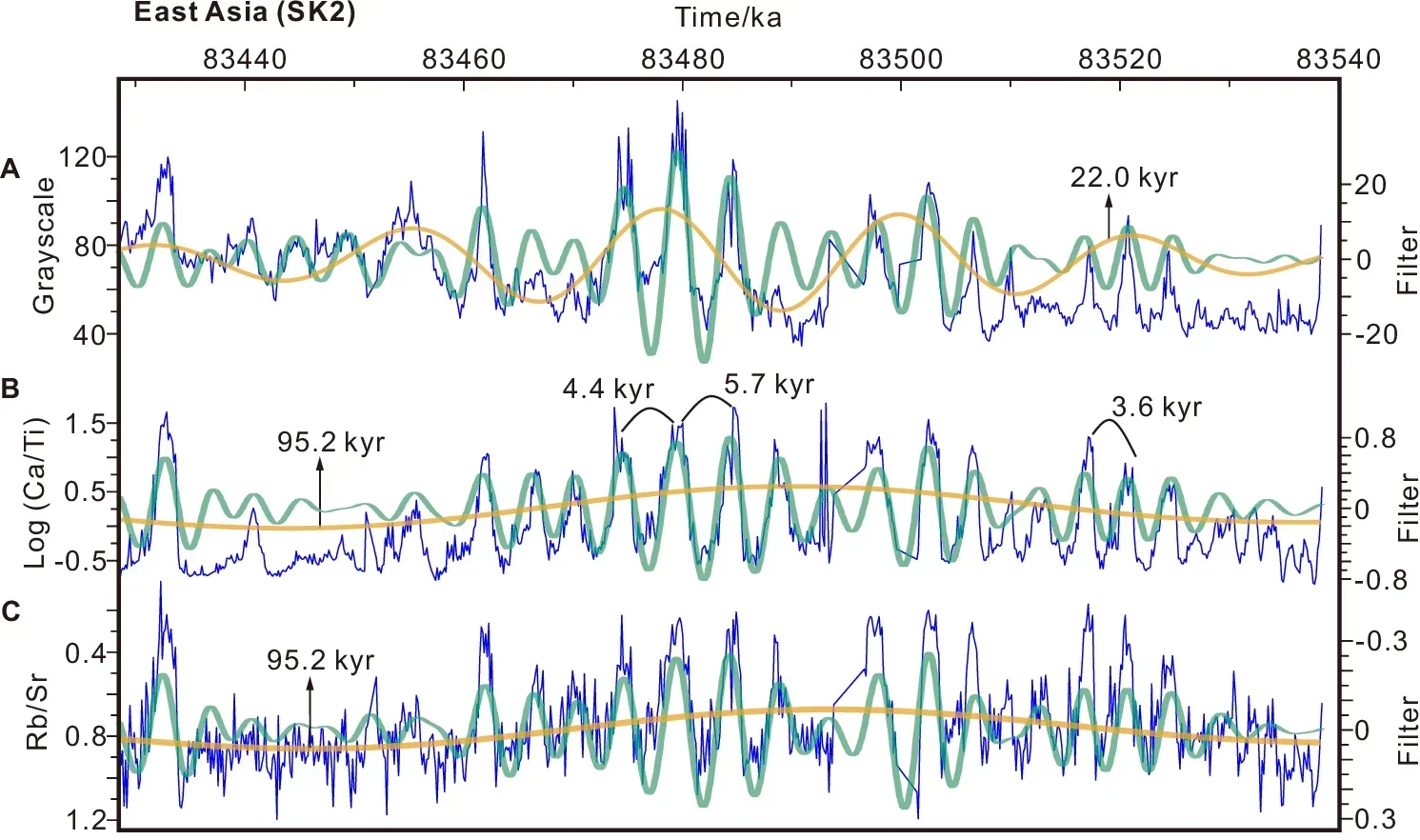

The team studied a rhythmic slice of the SK2 drill core. The interval spans 83.428 to 83.538 million years ago. It sits within the lower Nenjiang Formation. In the core, dark, silica-rich mudstone alternates with gray, carbonate-rich layers. A deep-lake setting matters because it reduces random local sediment shifts.

To track climate shifts closely, the scientists sampled at very fine spacing. They measured grayscale changes and key chemical ratios. One ratio, Rb/Sr, reflects chemical weathering strength. Another, log(Ca/Ti), tracks lake conditions linked to dryness and salinity. Higher Ca/Ti points to lower lake levels and drier conditions.

The team also examined a marine record from the low-latitude South Atlantic. They revisited a core from DSDP–516F. Earlier work hinted at short cycles there, but dating was uncertain. The new study improved the timeline using magnetostratigraphy and cyclostratigraphy.

The marine record relied on color reflectance values called L*. Sampling was also high resolution. The interval spans 81.473 to 80.702 million years ago. The researchers tuned the time scale using the TimeOpt method. That approach helped estimate sedimentation rates and align cycles more confidently.

“Using both a lake record and an ocean record strengthened the test. If similar rhythms appear across hemispheres and settings, a broader driver becomes more likely. A local quirk becomes less convincing,” Wang told The Brighter Side of News.

“In both archives, our team found climate variability on timescales of thousands of years. The strongest signal clustered around 4 to 5 thousand years,” he continued.

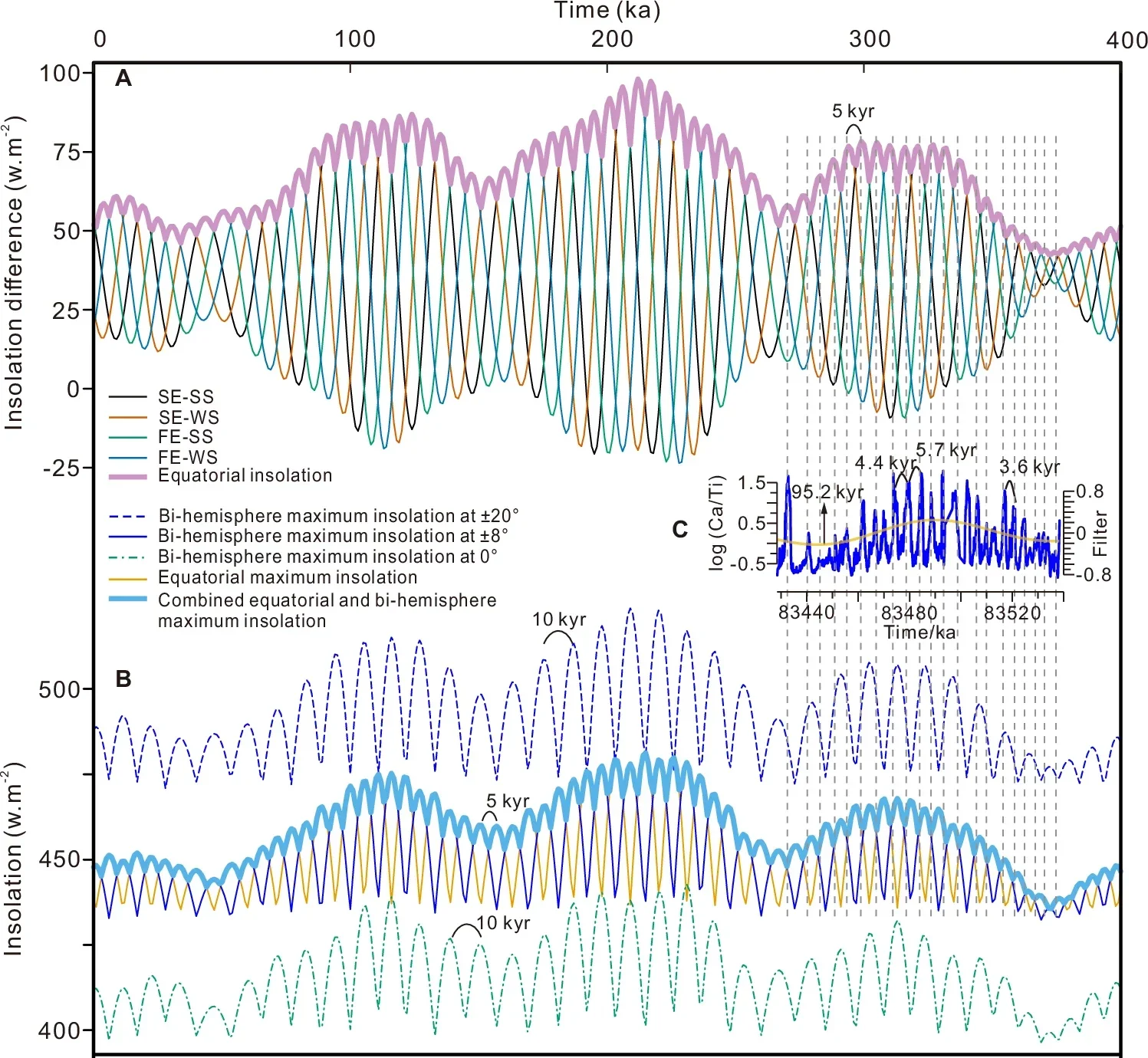

The engine behind the new explanation begins with precession. Earth’s axis wobbles like a spinning top. One full wobble takes about 26,000 years. When that wobble interacts with the slow rotation of Earth’s elliptical orbit, it produces two main precession cycles. Those cycles are about 19,000 and 23,000 years.

Precession changes how sunlight falls across seasons and hemispheres. At the equator, sunlight has a distinctive pattern. Solar energy peaks near the equinoxes and dips near the solstices. That geometry can create four strong “beats” in seasonal contrast within one precession cycle. In theory, this yields a quarter-precession rhythm near 5,000 years.

The Songliao Basin data match that expectation. The proxies shift together in a consistent pattern. Higher grayscale and higher Ca/Ti align with lower Rb/Sr. Mineral evidence links those layers to carbonate-rich mudstones. The team interprets those as arid phases with lower lake levels. The opposite layers suggest humid phases. More rain boosts weathering, raises lake levels, and increases runoff.

The marine record showed a similar rhythm. Spectral analysis found peaks near 5.5, 4.8, and 4.1 thousand years. It also showed that each precession cycle subdivided into smaller repeats. Each precession cycle contained two semi-precessional cycles and four quarter-precessional cycles. That repeating “quadripartite” structure fit the quarter-precession idea.

The study also found that the strength of the 4-to-5-thousand-year swings rose and fell with longer orbital cycles. Those longer cycles reflect eccentricity, or how stretched Earth’s orbit becomes. The team reports modulation near about 100,000 years and 405,000 years. That linkage supports an orbital origin.

Not every peak was treated as a direct orbital “clock.” The researchers argue that some shorter cycles; such as 1.8 to 4 thousand years; can emerge through nonlinear climate responses. Others may reflect interactions among the main precession-related frequencies. The marine record required extra caution for the shortest cycles because sediment mixing can blur very fast signals.

The results reshape how you can think about climate stability in a warming world. The Late Cretaceous had no big ice sheets to collapse. Yet it still swung between wetter and drier states. The driver appears tied to predictable orbital mechanics.

The study also frames the Cretaceous as a useful comparison for modern risk. “During the Late Cretaceous, atmospheric CO₂ levels reached about 1,000 parts per million—comparable to projections for the end of this century,” says Prof. Michael Wagreich, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Vienna. “This makes the Cretaceous greenhouse climate a meaningful analogue for understanding Earth’s future.”

The authors stress that orbital cycles will not stop. “Because Earth’s orbital configuration will remain stable for billions of years, the unveiled close link we identified between astronomical precession and millennial-scale climate cycles implies that high-frequency climate oscillations, like those seen in the Cretaceous, could also emerge in a warmer future—potentially in ways that are more predictable than previously thought,” concludes the study’s first author, Zhifeng Zhang.

These findings matter because they widen the list of ways climate can change quickly. You cannot assume that losing ice sheets ends abrupt shifts. The study suggests that even in a hot world, rainfall patterns can swing on thousand-year scales.

For researchers, the work offers a clearer target for climate models. If quarter-precession forcing can organize fast variability, models can test when and where such swings amplify. That can sharpen long-term projections for monsoons, drought risk, and ocean-atmosphere connections.

For society, the benefit is not a forecast of a sudden movie-style freeze. The value is a stronger warning about instability. A warmer climate may still carry natural “pulses” that reshape water supply over long spans. Understanding those pulses can improve planning for agriculture and infrastructure. It can also guide future field campaigns that look for similar rhythms in other warm periods.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Slow orbital wobbles drove drastic climate swings on Earth appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.