Low Earth orbit no longer feels distant or empty. On a clear November night, a Falcon 9 rose from Cape Canaveral and released 29 Starlink satellites into a busy band of sky about 340 miles up. The launch looked routine. It was anything but. By late November, SpaceX had logged 152 Falcon 9 missions in 2025 alone, a company record. Across the globe, Europe, China, India, Japan, Russia, Israel, and South Korea also sent hardware aloft. This year’s total will approach 300 orbital launches for the first time.

Jonathan MacDowell, who tracks flights for Harvard and the Smithsonian, says the surge is hard to grasp. “We’re now at 12,000 active satellites, and it was 1,200 a decade ago, so it’s just incredible.” Industry filings hint that the count could climb toward 100,000 within two decades.

As constellations swell, a quieter crisis grows with them: the trash.

Millions of lifeless objects whirl above you at up to 17,000 miles per hour. They range from dead satellites and spent rocket stages to shards from long-ago crashes. Even a chip the size of a grain of rice can punch a hole through a spacecraft. The European Space Agency estimates more than 34,000 large debris objects alone, most in low orbit.

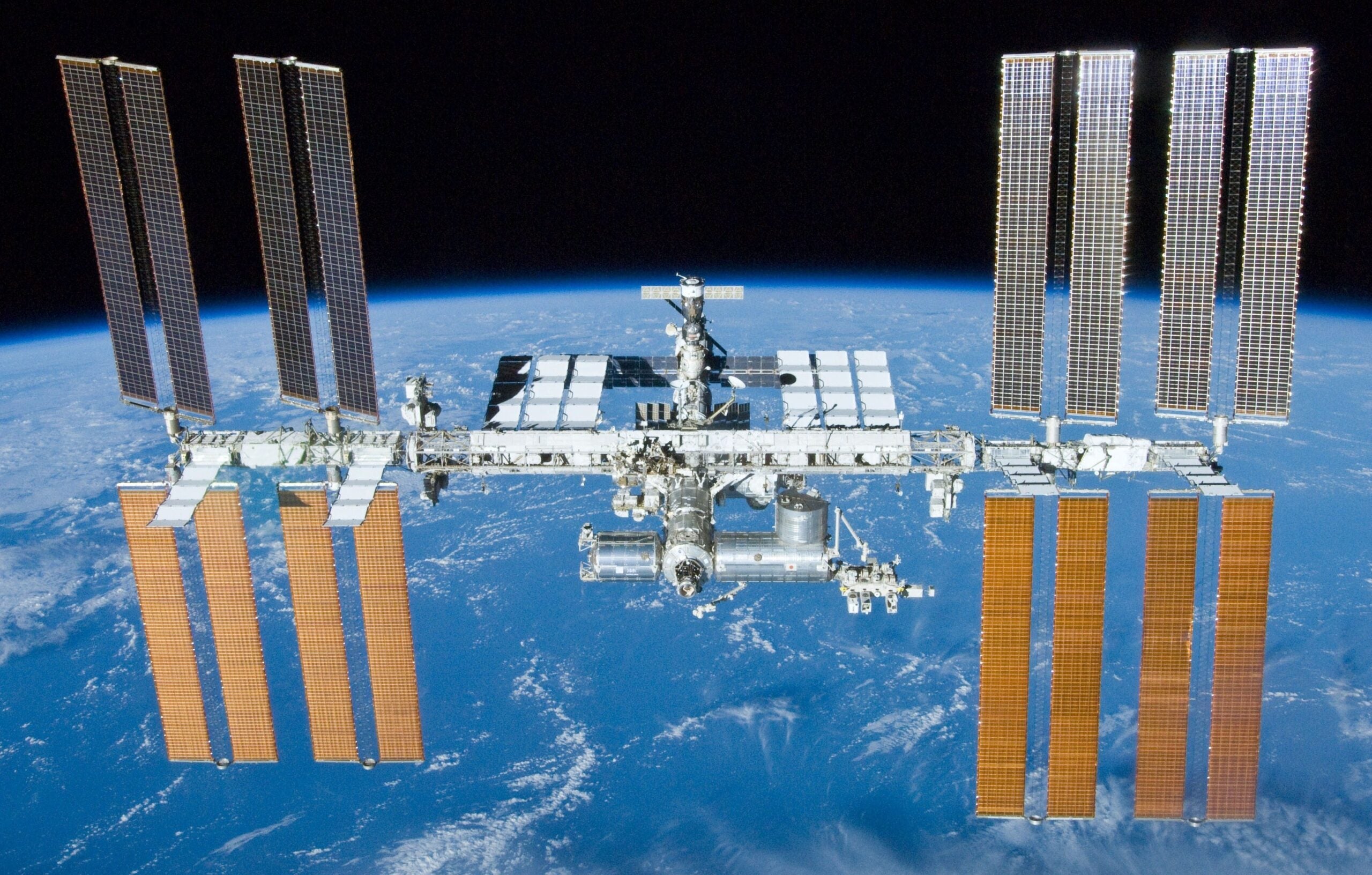

Assistant Professor Hao Chen, who studies space systems, puts it plainly. “Even if a tiny, five-millimeter object hits a solar panel or a solar array of a satellite, it could break it. And we have over 100 million objects smaller than one centimeter in orbit.” Crews on the International Space Station sometimes shelter in capsules when alerts spike. Every warning, every maneuver, every near miss costs money and risk.

Living with space junk is not free. Operators pay for alerts, course changes, fuel, and repairs. Worst of all is a collision, which can destroy a satellite and spray thousands of fragments that linger for decades. That chain reaction, known as a cascade, raises the odds of the next crash.

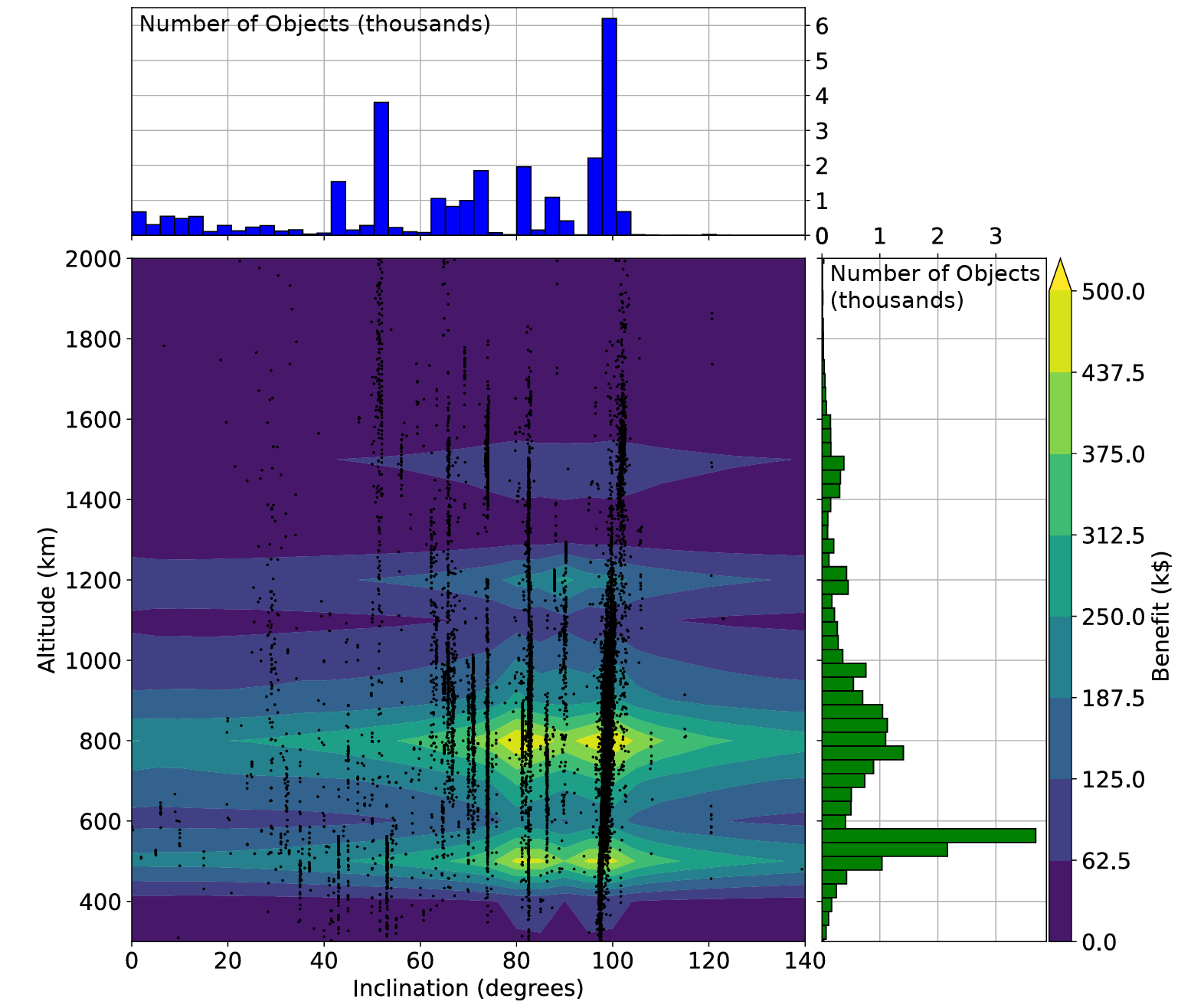

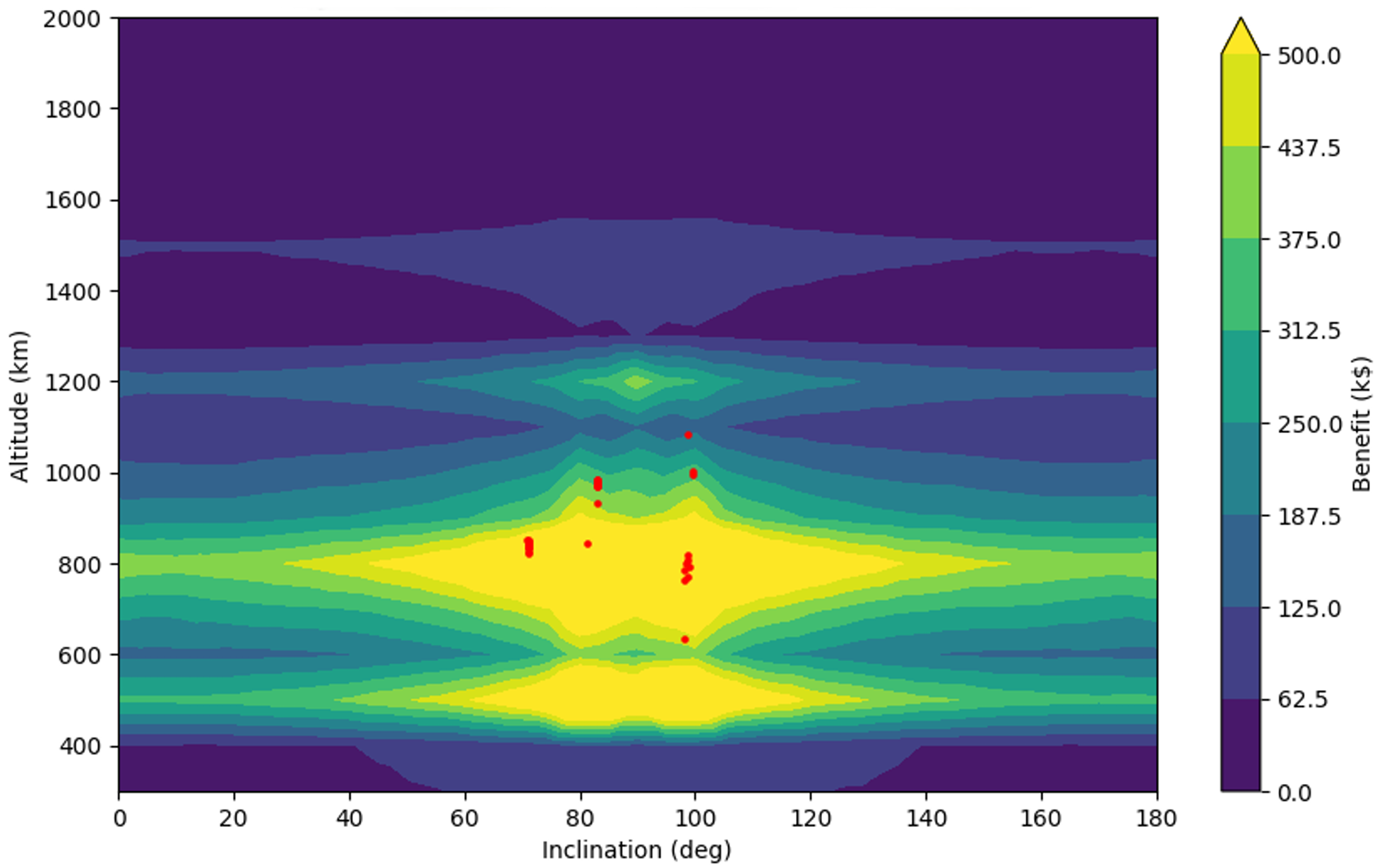

A new study asked a blunt question: Could a profit motive finally push cleanup beyond talk and into action? In “Space Logistics Analysis and Incentive Design for Commercialization of Orbital Debris Remediation,” published in Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, Chen and colleagues tested whether private firms could make money by removing the worst offenders, and how to split the gains fairly.

The team used a collision model that estimates how often a piece of debris would trigger alerts, force a maneuver, or cause a crash in a typical year. Each event carries a price tag, from hundreds of dollars for alarms to hundreds of millions for a wreck. Remove one object, and you avoid its future bills.

They also counted the hidden risk: what happens if a large hulk shatters. Past work suggests a single smash can spawn about 3,000 fragments. Spread across height and tilt, those pieces haunt busy orbits for years. Take away one big threat, and you also block a cloud of future danger. The study rolls this into a measure the authors call “debris-years,” an estimate of how long risks would linger if an object stayed aloft.

The research tested three cleanup paths, each carried out by a service satellite that captures debris.

Uncontrolled return brings junk down to about 350 kilometers. Drag does the rest. It is cheaper, but the landing spot is uncertain. Controlled return lowers debris to roughly 50 kilometers, then guides it into the air. It costs more fuel, but it reduces danger on the ground. Recycling ferries trash to a factory in orbit. Metals, mainly aluminum, are reclaimed for new builds, saving launch costs from Earth.

Chen explains the math behind the lure of recycling. “It takes about $1,500 per kilogram to launch anything from Earth to space. So if you don’t have to launch from Earth, it’s a benefit.”

The team treated cleanup like a delivery network in the sky, with routes, fuel tanks, time windows, and vehicle limits. They priced launches, vehicles, fuel, and operations, then aimed to remove the 50 most risky objects first.

Results surprised even the team. For both return methods, benefits overtook costs after about 20 to 21 objects. At that point, avoided crashes and maneuvers saved more money than the missions spent. Recycling, though, was trickier. It only crossed into profit with more than about 35 objects and stayed there if recovery rates were high.

Costs also hinged on launch prices. If sending mass skyward gets expensive, the margin shrinks. Recycling becomes fragile if less metal can be recovered. On the flip side, debris high above Earth can circle for centuries. If removal averts risks for longer than assumed, the payoff grows fast.

Here is the rub. Debris removers foot the bill. Satellite firms reap the safety. Without a nudge, no one rushes to clean.

Chen’s group borrowed an idea from game theory to propose a deal. Operators would pay a fee equal to a share of the savings from a cleaner sky. That money becomes the incentive for the cleanup crew. The best split, the paper argues, is one that leaves both sides better off than before. The math points to a wide zone where that happens, especially for the cheaper, uncontrolled returns.

“We will need some agency to create an incentive for the debris remediators,” Chen says. “The money should come from the people who enjoy all those benefits.” He adds, “Our analysis shows that there is a surplus to be generated from the remediation of orbital debris, and that surplus can be optimally shared by space operators and debris remediators.”

Trash in orbit is only half the story. The other half rains through your air.

When satellites die, many are designed to burn up. Their vapor condenses into fine particles that drift into the stratosphere. A field study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found traces of aluminum, copper, lithium, and even niobium in high-altitude samples. Aluminum oxide is the standout worry. A paper in Geophysical Research Letters estimates one satellite can yield about 70 pounds of these particles, which may hover for decades and nibble at ozone.

Rockets add their own scars. The most common fuel, refined kerosene, sheds soot high in the atmosphere. Models led by Christopher Maloney at the University of Colorado suggest that black carbon could warm the stratosphere by up to 1.5 degrees Celsius in a heavy-growth future, thinning ozone over the north.

Liquid methane burns cleaner but tempts with scale. SpaceX hopes to fly Starship often, perhaps daily someday. Eloise Marais of University College London warns the math cuts both ways. “The amount of black carbon emissions from burning LNG may be 75 percent less than from RP-1. But the issue is that the Starship rocket is so much bigger. There’s so much more mass that’s being launched.”

Jonathan MacDowell ties it together. “We are now in this regime where we are doing something new to the atmosphere that hasn’t been done before.”

Europe is moving first. The European Space Agency held a workshop in September and plans two years of field campaigns. NASA scientists have sketched a similar plan, but budgets wobble.

Designs may shift too. Some engineers now talk about “design to survive,” not burn. Atmos is testing an inflatable shield to bring cargo home. Japan’s space agency flew a wooden satellite to test safer materials. Former NASA engineer Moriba Jah urges a circular economy in orbit with modular parts that can be reused.

Rules will matter as much as tech. “Regulations often translate into additional costs,” Marais says, “and that’s an issue, especially when you’re privatizing space.” Andrew Lawrence of the University of Edinburgh worries growth alone cannot guide the future. He calls for goals closer to zero impact. “I thought we were safe,” he admits. “But no, we’re not.”

The sky is no longer just a view. It is a neighborhood, and it is getting crowded.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Space is filled with junk, and scientists say it is time to start cleaning appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.