On a warming planet, your food supply depends on crops that can survive heat, drought and fast spreading disease. Now engineers at the University of California San Diego have built a spray on shield for plants that could help them endure both bacterial infections and dry spells.

Published in ACS Materials Letters, the work points to a future where farmers might protect fields with a simple mist, not just heavy chemicals. It also hints at a new way to tap into plants’ own defenses rather than replacing them.

Bacterial diseases already cause huge crop losses worldwide. Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria trigger wilt, blight, speck and canker in many major crops. As temperatures rise, these pathogens are moving into new regions, so fields meet more unfamiliar threats each season.

At the same time, drought is hitting farms more often and more intensely. When plants are thirsty, they weaken and become easier targets for infection. That double hit threatens the food on your plate and pushes up prices at your grocery store.

Current tools, including many pesticides and antibiotics, can help but bring problems. They may harm non target organisms, leave residues and lose power as microbes evolve resistance. Farmers and scientists are looking for plant friendly tools that are tougher on bacteria and gentler on everything else.

To address that need, researchers from the labs of Jon Pokorski and Nicole Steinmetz joined forces at UC San Diego’s Jacobs School of Engineering. Their goal was direct: create a coating that sticks to leaves, kills bacteria and does not choke the plant.

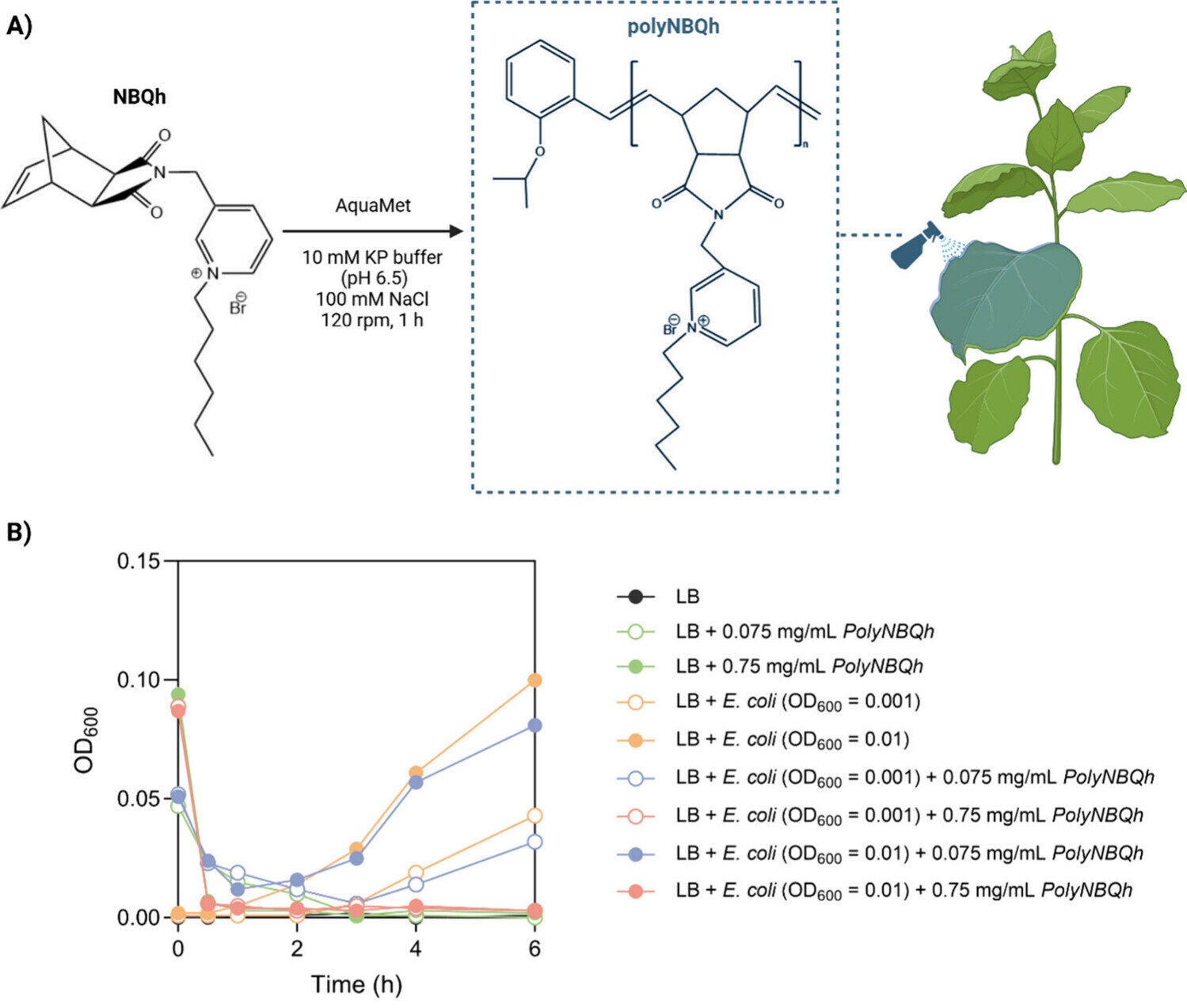

The team designed a synthetic polymer with positively charged chemical groups along its backbone. Those positive charges interact with bacterial membranes and disrupt them, which helps kill a wide range of harmful microbes.

The key twist came from how they made the material. “Typically, polymers are synthesized using organic solvents that are toxic to plants,” said co first author Luis Palomino, a chemical and nano engineering Ph.D. candidate in Pokorski’s lab. “What we did differently here is we made the polymer in buffer conditions in water.”

That change sounds simple, but it matters for you and for farmers. It means the material can be dissolved directly in water and sprayed, without plant harming solvents or complicated steps. The polymer belongs to a class called polynorbornene and is permeable to gases, so coated leaves can still breathe and grow.

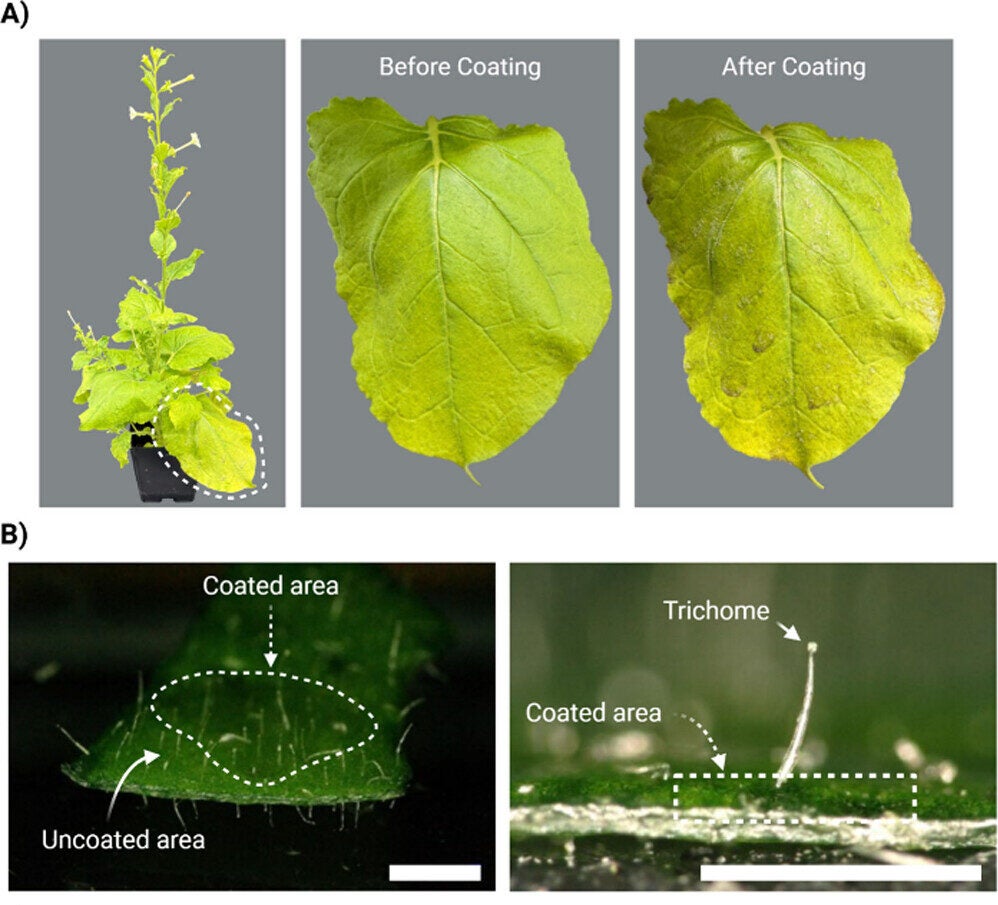

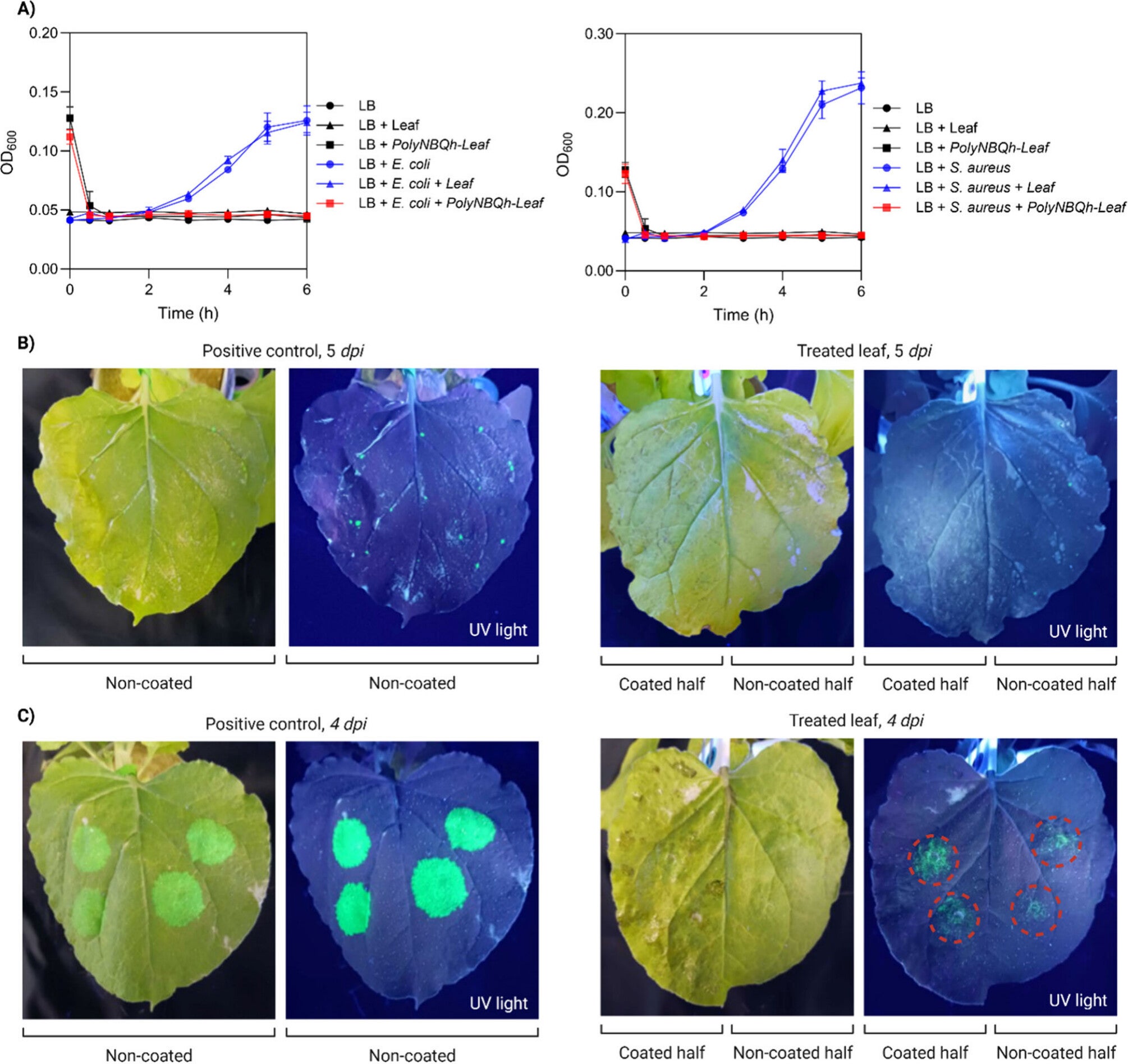

The scientists sprayed their formulation onto leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana, a plant widely used in labs and molecular farming. Then they challenged those leaves with Agrobacterium, a bacterium often used in plant research that can also act as a pathogen.

Coated plants resisted infection. In separate tests with detached leaves in petri dishes, the spray also suppressed Gram negative Escherichia coli and Gram positive Staphylococcus aureus. That broad activity suggests the coating may one day help protect many different crops in the field.

One result surprised even the research team. “Full leaf coverage was not necessary to achieve protection,” said co first author Patrick Opdensteinen, a postdoctoral researcher in Steinmetz’s lab. “We can spray just a small part of the leaf, and that translates to bacterial immunity for the whole plant. That was a really cool outcome.”

Why would treating a small patch shield the entire plant. The team traced a possible answer in one of the plant’s early stress signals. Leaves that received the polymer briefly showed a mild spike in hydrogen peroxide.

“Hydrogen peroxide is not just a disinfectant in your bathroom cabinet. In plants, it also works as a signaling molecule that spreads the message that stress has arrived. In this study, the signal was short lived, then declined as the plant returned to a healthy state,” Palomino told The Brighter Side of News.

The researchers suspect that this short pulse may prime defenses throughout the plant. In other words, the coating may not only kill bacteria on contact, it may also teach the plant to stay alert. That combined effect could explain why limited coverage goes a long way.

From your perspective as a consumer, that efficiency matters. It suggests farmers might need less material per acre, which can lower costs and reduce environmental burden.

The spray delivered a second benefit that could matter just as much in a hotter world. When the team withheld water for four days, treated plants stayed greener and less wilted than untreated ones.

The scientists think the polymer may act as a thin physical barrier that slows water loss from leaf surfaces. At the same time, the mild stress signal it triggers could awaken deeper drought tolerance pathways inside the plant.

For growers, that combination is powerful. A single treatment that helps plants fight disease and stay upright through short droughts could buy precious time during heat waves and irrigation failures. For you, it means crops may keep producing even when conditions turn harsh.

The work is still in its early stages. The coating has only been tested under controlled conditions on model plants, not yet in complex farm environments. The team now plans to dig deeper into how the polymer triggers whole plant immunity and drought resilience.

Another major focus is environmental safety. The engineers want to improve biodegradability so the polymer breaks down cleanly in soil and water. They will also study toxicity in greater detail, to be sure the coating does not harm beneficial microbes, insects or other wildlife.

“Our hope is to use this in the field to benefit agriculture, and this is the first step,” Opdensteinen said. “There’s a lot of potential for plant protection.”

If future tests on real crops and real farms go well, the spray could become one tool in a broader toolbox, alongside better breeding, soil health and smarter irrigation. It will not fix every problem, but it might help keep more plants alive long enough to feed more people.

For farmers, a water based, gas permeable antibacterial coating could offer a new way to protect crops without relying solely on conventional chemicals. The ability to confer whole plant protection from partial coverage might lower application costs and reduce environmental load.

For scientists, the study opens fresh questions about how synthetic materials can tap into natural plant signaling. Understanding that cross talk may lead to new treatments that combine physical protection with immune priming and drought resilience.

For society, this approach could strengthen global food security as climate change intensifies disease pressure and water stress. A simple spray that helps plants resist infection and stay hydrated longer could stabilize yields, reduce losses and support farmers in vulnerable regions.

Research findings are available online in the journal ACS Materials Letters.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Spray on polymer shield helps plants fight bacteria and survive drought appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.