In the damp understory of forests in Taiwan, mainland Japan, and Okinawa, a plant called Balanophora can fool you at first glance. Its knobby flower stalks look more like a mushroom than a flowering plant. Yet it is a plant, and a deeply unusual one: it lives almost entirely underground, fused to a host’s roots and drawing everything it needs from that host.

That strange lifestyle is at the center of a new genetic survey led by researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), Kobe University, and the University of Taipei. The team’s work, published in New Phytologist, tracks how several Japanese and Taiwanese Balanophora species evolved as parasites and how they keep running core chemistry despite discarding the machinery most plants use to live.

Study lead author Dr. Petra Svetlikova, a science and technology associate at OIST, summed up the puzzle like this: “Balanophora has lost much of what defines it as a plant, but retained enough to function as a parasite. It’s a fascinating example of how something so strange can evolve from an ancestor that looked like a normal plant with leaves and a normal root system.”

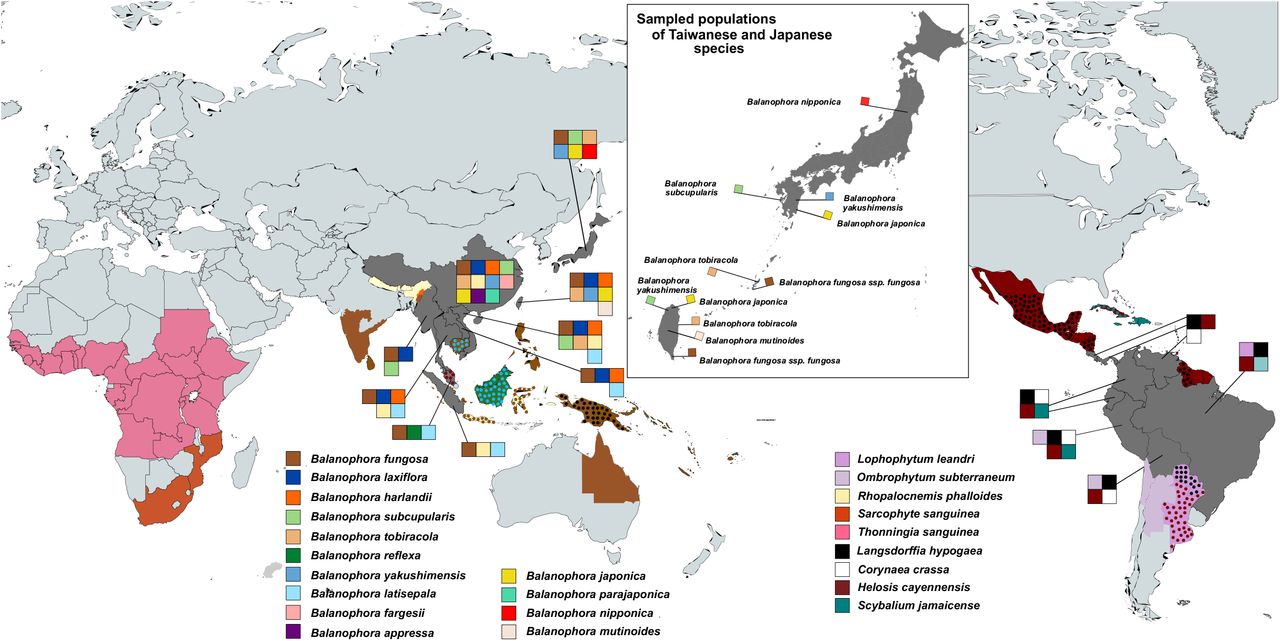

The researchers sampled seven of the eight known Balanophora species across 12 populations in Taiwan and Japan. They also worked with specialists in parasitic plants, including Dr. Huei-Jiun Su and Dr. Kenji Suetsugu, to reach populations that are rare and hard to access. By sequencing plastid genomes and nuclear transcriptomes, the team built a clearer family tree for the genus and looked for clues about how parasitism reshaped its cells and its reproduction.

A key focus was the plastid. Plastids are plant cell structures that include chloroplasts, which power photosynthesis in green plants. Balanophora has no chlorophyll and does not photosynthesize, but it still carries plastids. What the study shows is that these plastids have been stripped down to a startling degree without becoming irrelevant.

Across six Japanese and five Taiwanese samples, the team assembled complete plastid genomes that ranged from about 14,259 to 16,290 DNA “letters” long. In most photosynthetic plants, plastid genomes typically span roughly 120,000 to 170,000 base pairs. Here, the genome is a fraction of that size, with an extremely low GC content of about 12 to 13 percent.

What remains is a tiny gene set dominated by ribosomal components and other genes tied to basic gene expression in the plastid, plus a single transfer RNA gene, tRNA-Glu (trnE). The team also reported new plastid genomes for five species that had not been sequenced in this way before, expanding the limited dataset that earlier studies had to rely on.

Even within that minimalist world, there were surprises. One species, B. tobiracola, carried the largest plastid genome in the genus reported so far and encoded 16 protein-coding genes. The team also found signs that ycf1, a gene linked to protein import across plastid membranes, remains functional because a transmembrane domain is still detectable.

To check that these tiny genomes were assembled correctly, the researchers compared results from two assembly approaches. Some samples matched perfectly. Others differed, sometimes because one approach produced incomplete fragments. The mismatches could also hint at real biological variation, such as multiple plastid genome variants in the same plant.

“Perhaps the most striking molecular twist involved the genetic code itself. In many organisms, the DNA sequence TAG signals “stop.” In these plastid genomes, TAG appears to have been reassigned to code for tryptophan. Our study found in-frame TAG codons inside many plastid genes across all examined Balanophora plastomes, supporting the idea that this alternative code is widespread in the family,” Dr. Svetlikova told The Brighter Side of News.

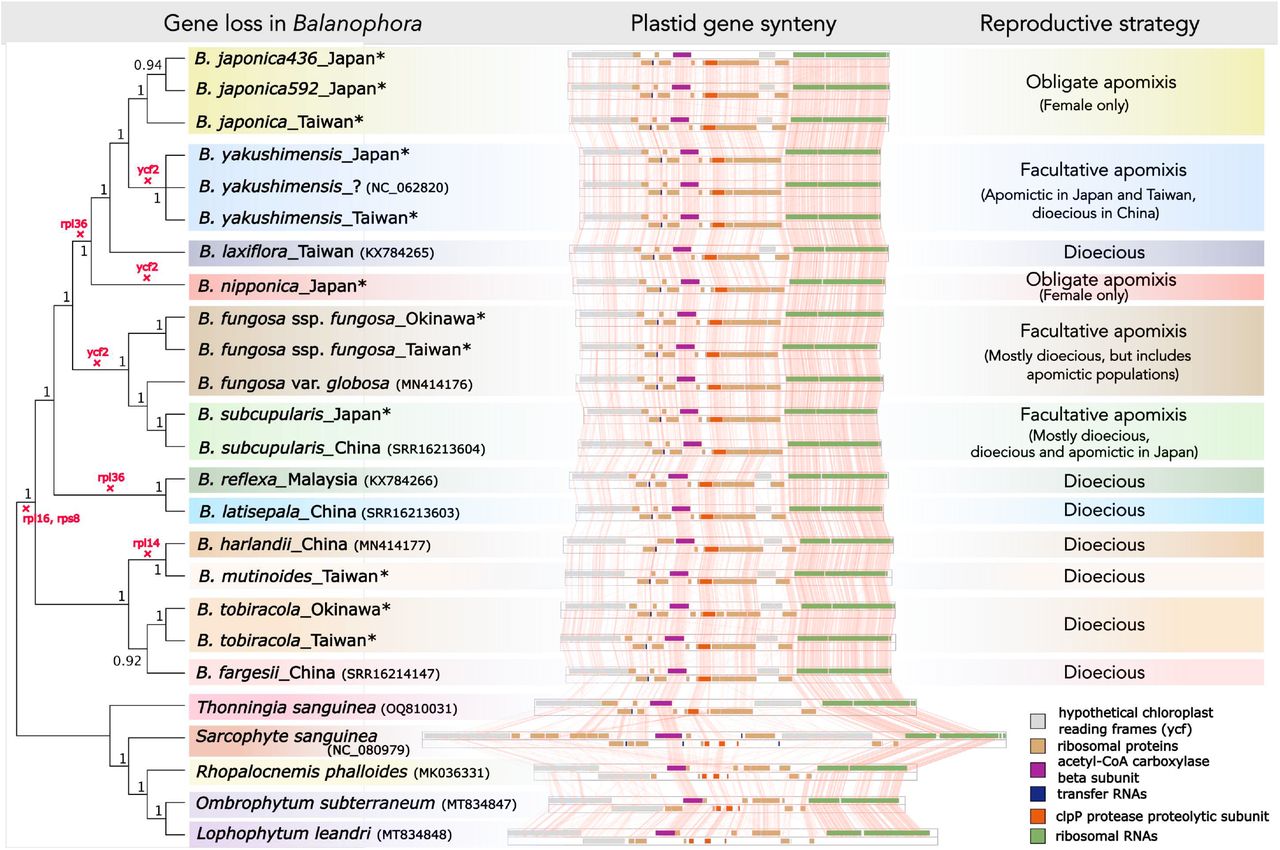

Using plastid gene datasets that included rRNA genes and plastid protein-coding genes, the researchers reconstructed evolutionary relationships with two main methods and recovered four major clades within Balanophora. The sampling helped place Japanese and Taiwanese populations side by side, instead of treating island groups as isolated curiosities.

Plastid genomes offer one view of ancestry, but nuclear genes provide another. The team built trees using nuclear 18S rRNA and large transcriptome-based gene sets. Those nuclear analyses broadly supported the plastid-based relationships, while also exposing a practical problem: not all public datasets are what they claim to be.

One transcriptome labeled as B. harlandii in public archives appeared to be misidentified and instead likely belonged to the B. fungosa clade. That kind of mix-up can ripple through a field where rare plants limit sample sizes and where single datasets can shape early conclusions. The authors argued that broader sampling across the family, paired with careful “phylotranscriptomics,” will reduce these errors and tighten species boundaries.

The team also measured transcriptome completeness and flagged signs of duplicated genes. Some of that duplication may come from normal transcript variation, but contamination is also a risk because Balanophora tissues sit in intimate contact with host roots. To reduce mistakes, the researchers leaned on single-copy genes for key analyses and manually inspected alignments.

All of this matters because Balanophora sits in a family, Balanophoraceae, that is entirely parasitic. The study notes that the family diversified in the mid-Cretaceous, around 100 million years ago. That deep history makes it a useful system for understanding how plant lineages change once photosynthesis is abandoned.

The work pushes back on a simple story that these plants “lost photosynthesis and became reduced.” Instead, the data point to a reworked cellular division of labor. Although the plastid genome is tiny, the plastid organelle still appears busy because the nucleus supplies it with proteins.

Using computational predictions, the researchers estimated that hundreds to thousands of proteins may be targeted to plastids, depending on the sample and filtering stringency. Even with conservative criteria, the high-confidence set often landed in the hundreds. Those proteins mapped to pathways that have nothing to do with capturing sunlight, including steps in amino acid production, fatty acid synthesis, heme, riboflavin, lipoic acid, and isoprenoids through the MEP pathway. Core carbohydrate routes such as glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway also appeared in the functional picture.

Professor Filip Husnik, who leads OIST’s Evolution, Cell Biology, and Symbiosis Unit, highlighted why this matters: “That Balanophora plastids are still involved in the biosynthesis of many compounds unrelated to photosynthesis was surprising. It implies that the order and timing of plastid reduction in non-photosynthetic plants is similar to other eukaryotes, such as the malaria-causing parasite, Plasmodium, which originated from a photosynthetic ancestor,” says Professor Filip Husnik, head of the Evolution, Cell Biology, and Symbiosis Unit at OIST.

The study also draws attention to how Balanophora reproduces, especially on islands. Many species are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers occur on separate plants. Yet in Japan and Taiwan, some species and populations produce seeds without fertilization. Two species, B. japonica and B. nipponica, consist solely of female individuals and reproduce strictly through obligate apomixis.

Obligate apomixis is rare because purely asexual lineages can lose genetic flexibility and accumulate harmful mutations over time. Dr. Svetlikova put it plainly: “Obligate agamospermy is exceedingly rare in the plant kingdom, because it typically carries a lot of negative downsides – lack of genetic diversity, accumulation of bad mutations, dependence on specific conditions, higher extinction risk, and so on,” explains Dr. Svetlikova. “Fascinatingly, we found that the obligately agamospermous Balanophora species were all island species – and we speculate that more Balanophora species may be facultative, or even obligate, agamosperms.”

That island pattern hints at an advantage that matters during long-distance dispersal. If seeds land on a new island, a single female plant could establish a population without needing a mate. The study frames this as consistent with “uniparental reproduction” aiding colonization, especially in niche habitats where even finding the right host tree can be hard.

Host choice adds another layer of vulnerability. Balanophora populations often parasitize only a few local tree species. That tight ecological tie makes the plants sensitive to habitat loss, logging, and collection. Svetlikova said the team relied on local support to do the work, and she emphasized the stakes: “Most known habitats of Balanophora are protected in Okinawa, but the populations face extinction by logging and unauthorized collection. We hope to learn as much as we can about this fantastic, ancient plant before it’s too late. It serves as a reminder of how evolution continues to surprise us.”

This research sharpens how scientists think about what it means to “lose” a major biological function. Instead of treating photosynthesis loss as a simple deletion, the study shows how a plant can keep plastids, shrink their genomes to a sliver, and still rely on those organelles for essential chemistry. That helps researchers predict what might happen in other non-photosynthetic plants and improves the search for the minimal genetic toolkit needed to keep organelles running.

The work also matters for evolutionary biology because it ties extreme asexual reproduction to island life in a rare plant group. If asexual seed formation can support colonization and persistence in isolated habitats, it may explain how some lineages survive despite the usual costs of cloning. That could guide future studies of plant reproduction, genome stability, and how species diversify when mates are scarce.

Finally, the study carries clear conservation value. By mapping species relationships and identifying where rare reproductive systems occur, the research can help local agencies and botanists prioritize protection of specific habitats and populations. Better genetic identification also reduces the risk of mislabeling in public databases, which can steer future conservation plans and scientific studies in the wrong direction.

Research findings are available online in the journal New Phytologist.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Strange parasitic ‘mushroom’ plant abandoned photosynthesis and somehow flourished appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.