The problem with prequels, the mode du jour in Hollywood’s grab-all-the-IP age, is they make the mistake of thinking our appreciation of something is the same as curiosity about its provenance. In Solo: A Star Wars Story, learning how the roguish smuggler Han got his last name punctures the illusion of his devil-may-care aura, a deflating answer to a question that didn’t need to be posed in the first place. Dune: Prophecy is the latest franchise to prove the fault of this approach. When a character complains, “We are all just pieces on the board,” the realization that all their moves have been predetermined applies to the whole show. Dune: Prophecy’s derivativeness is both its greatest flaw and its most defining characteristic.

An adaptation of the 2012 novel Sisterhood of Dune by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson, Dune: Prophecy takes place 10,000-plus years before the events of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic Dune. That novel, and Denis Villeneuve’s two blockbuster films Dune and Dune: Part Two, followed the ascendence of Paul Atreides, who avenges his family’s destruction at the hands of rival House Harkonnen by accepting his role as the maybe-messiah of the Fremen, the indigenous people of the desert planet Arrakis. In doing so, Paul seizes control of Arrakis’s spice (the most valued resource in the universe) and rejects the influence of the Bene Gesserit space-witches. The religious order had spent millennia matchmaking to create the Kwisatz Haderach, a figure they want to crown as emperor and then control, and with their long black robes and inscrutable plans for Paul, these women serve as secondary villains in the Dune films. In Prophecy, they take on the role of antihero-ish protagonists, with the series sketching out their beginnings and first maneuverings to acquire power in the Imperium.

Dune: Prophecy is set at a pivotal moment in the history of the franchise, when humans rose up against the thinking machines who enslaved them and established various orders to specialize in the tasks the computers once handled. The Bene Gesserit become essential to the universe in the shadow of that rebellion, but rather than depict how thoroughly this revolution changed reality for the remaining humans, Dune: Prophecy settles for a more Game of Thrones-lite approach, where all disputes are really about surface-level politics (with some supernatural sandworm-related stuff as window dressing) and every so often there’s a sex scene to spice things up. (Literally, there’s a lot of casual spice drug use in this series.)

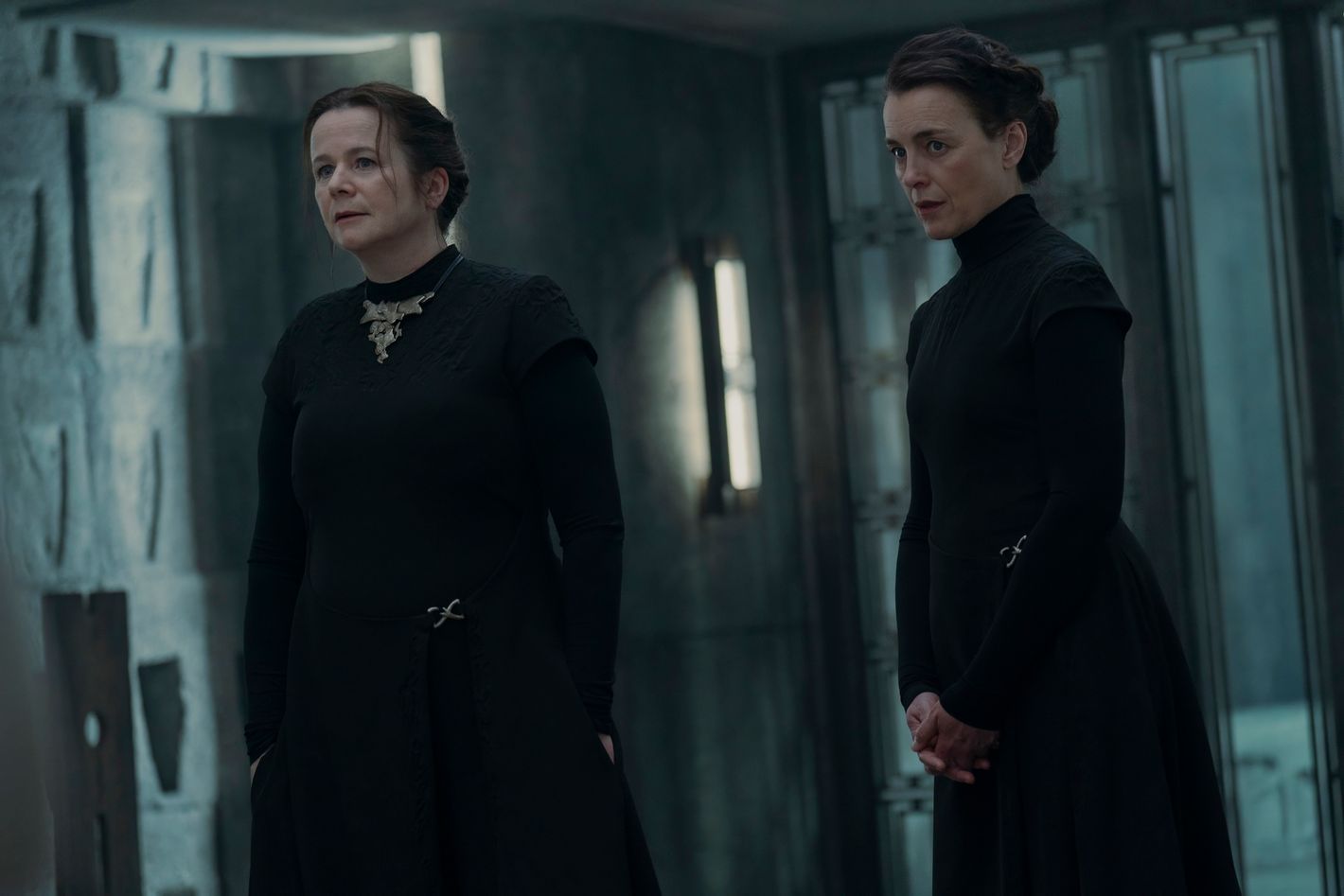

The series is primarily a portrait of Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother Valya Harkonnen (played by Jessica Barden as a teen and Emily Watson as an adult) as she eliminates competition within the order and rises to rule. Her endgame motivations are shadowy and unclear in the series’s first four episodes, but each installment alludes to her reasons for undermining Emperor Corrino (Mark Strong, mostly just looking befuddled) through conversations with her biological sister Tula (Olivia Williams), also a Reverend Mother who is more directly involved in teaching the Bene Gesserit acolytes than Valya — and more soft-hearted, too. Once Desmond Hart (Travis Fimmel), a veteran of 12 “tours” on Arrakis, starts undermining Valya’s authority with shocking powers of his own, the series divides its attention between Valya’s quest to determine what Desmond is up to and Tula’s mentoring of the Bene Gesserit sisters-in-training, teenage girls who begin to show a kind of hysteria that brings to mind the girls in Le Roy.

Watson and Williams are the series’s greatest assets, performers who approach each scene with shaded nuance and steely gravitas (sometimes more than the writing deserves) and who demonstrate a clear bond between the sisters even as they fall into a hierarchy. Tula’s concern for her young charges allows Dune: Prophecy to sprinkle in flashbacks to the Harkonnen sisters’ upbringing and explain how they both ended up in the order (with a number of Solo-like details about the Bene Gesserit’s mysterious ways, including information about their Voice power and their talent at lying that the series didn’t need to explain). As a teen, Valya was cast out by her family, and she begrudgingly found a home in the Sisterhood, where she made enemies with her ambition and insistence that the Imperium was wrong to banish the Harkonnens after the Great Machine Wars. As an adult, Valya has consolidated power to such a degree that she has no qualms telling Tula she expects “blind obedience” and no fear when she says to Desmond, “I would advise against playing games with me. I will win.” Through split timelines, this series is trying to do a misunderstood-feminism thing, with Valya and Tula’s youth defined by the burden of being members of the hated House Harkonnen, and their adulthood spent in an offensive posture against the people (mostly men) who despise but need them.

Like both of Villeneuve’s Dune adaptations, Prophecy continues to discard the religious and cultural elements of Herbert’s novel, particularly those that relate to Islam and the Middle East, and so central frictions between characters from different factions are gestured toward but never examined. A group of Bene Gesserit sisters are called “zealots,” while Desmond is positioned as a convert whose newfound faith in Shai-Hulud is a threat to Valya’s worldview. But without the context of how these perspectives contradict or diverge from each other, the characters’ conflicts feel weightless, and dialogue that directs them to state their objectives comes off empty. “The great houses are hoarding spice, forcing the people to turn to violence to get what they need to survive. The only way to stop this is to spill blood, and don’t doubt for a second my allegiance to the cause,” is thuddingly didactic.

That “here’s a character, here are a couple lines about their ethos, that’s all the development you get” approach means Dune: Prophecy often evokes the rhythms of second-tier YA. The Bene Gesserit trainees are defined only by their squabbles, and Sarah-Sofie Boussnina, who plays the emperor’s rebellious daughter Princess Ynez, is a particular victim of the series’s simplistic dialogue. When she finds her father dining with Desmond and snottily complains, “So we’re having breakfast with killers now?”, as if her family’s rule over the Imperium hasn’t resulted in the deaths of countless people, it’s impossible to tell whether Ynez is supposed to look like someone daring to speak truth to power or a delusional hypocrite. She might have the hardest go of it, but too many of Dune: Prophecy’s characters feel just as thin, their motivations and backstories never filled in.

The series is most intriguing when it offers up new glimpses of this world, even if the execution doesn’t always feel right. A shocking double murder at the end of the first episode puts onscreen the violence the series otherwise only gestures at. There appears to be just one nightclub on House Corrino’s home planet Kaitain, but the alternately flirty and paranoid scenes in that dingily lit bar offer something other than palace intrigue. Extended depictions of the “Agony,” the process by which a Bene Gesserit sister becomes a Reverend Mother by merging her consciousness with those of her ancestors, are visually horrifying, and explain the wonderfully spooky sound design of overlapping whispers and murmurs that pipe in during scenes with the order’s leaders. In those moments, Dune: Prophecy feels like it’s stretching itself to be something other than what we expect.

But too much else of Dune: Prophecy so tightly adheres to Villeneuve’s vision that the series feels like an act of cowardice and abdication of creativity. The ominous quote and exposition dump opening, the Bene Gesserit’s costumes, and technology like vibrating defensive shields all evoke the films so strongly, they seem desperate to promise fans that Dune: Prophecy will not be so different from those blockbusters. But why care about all the characters’ politicking, their worries about where their culture will end up, when the world they’re in now looks so much like the world 10,000 years from now? By hewing so closely to its predecessors, Dune: Prophecy undermines its own central tension, implicitly signaling to us that for a very long time, everything in this universe will be pretty much fine. The series’ treading-water quality feels like a portent, one that warns us Hollywood’s prequel formula won’t ever dare to change.