For years, sugar substitutes like aspartame, sucralose, and sugar alcohols have been promoted as safer choices for people trying to cut back on refined sugar. Grocery shelves are lined with “sugar free” snacks and drinks, and many consumers reach for them believing they pose little risk. But new research from Washington University in St. Louis suggests a different story. Scientists have uncovered evidence that sorbitol, one of the most widely used sugar alcohols, may quietly contribute to liver disease under certain conditions.

The work builds on years of research from the lab of Gary Patti, the Michael and Tana Powell Professor of Chemistry at Washington University. Patti’s team has spent more than a decade studying how fructose reshapes metabolism in ways that fuel diseases such as steatotic liver disease. In earlier studies, they showed how cancer cells can hijack fructose processing to grow faster, and how fructose overload drives fat buildup in the liver, a condition that affects nearly 30 percent of adults worldwide.

What startled Patti most in the new study was how closely sorbitol resembles fructose. “Because sorbitol is essentially one transformation away from fructose, it can induce similar effects,” he said. The finding suggests that sorbitol, despite being marketed as a low-calorie sweetener, may behave more like a cousin of fructose than a harmless alternative.

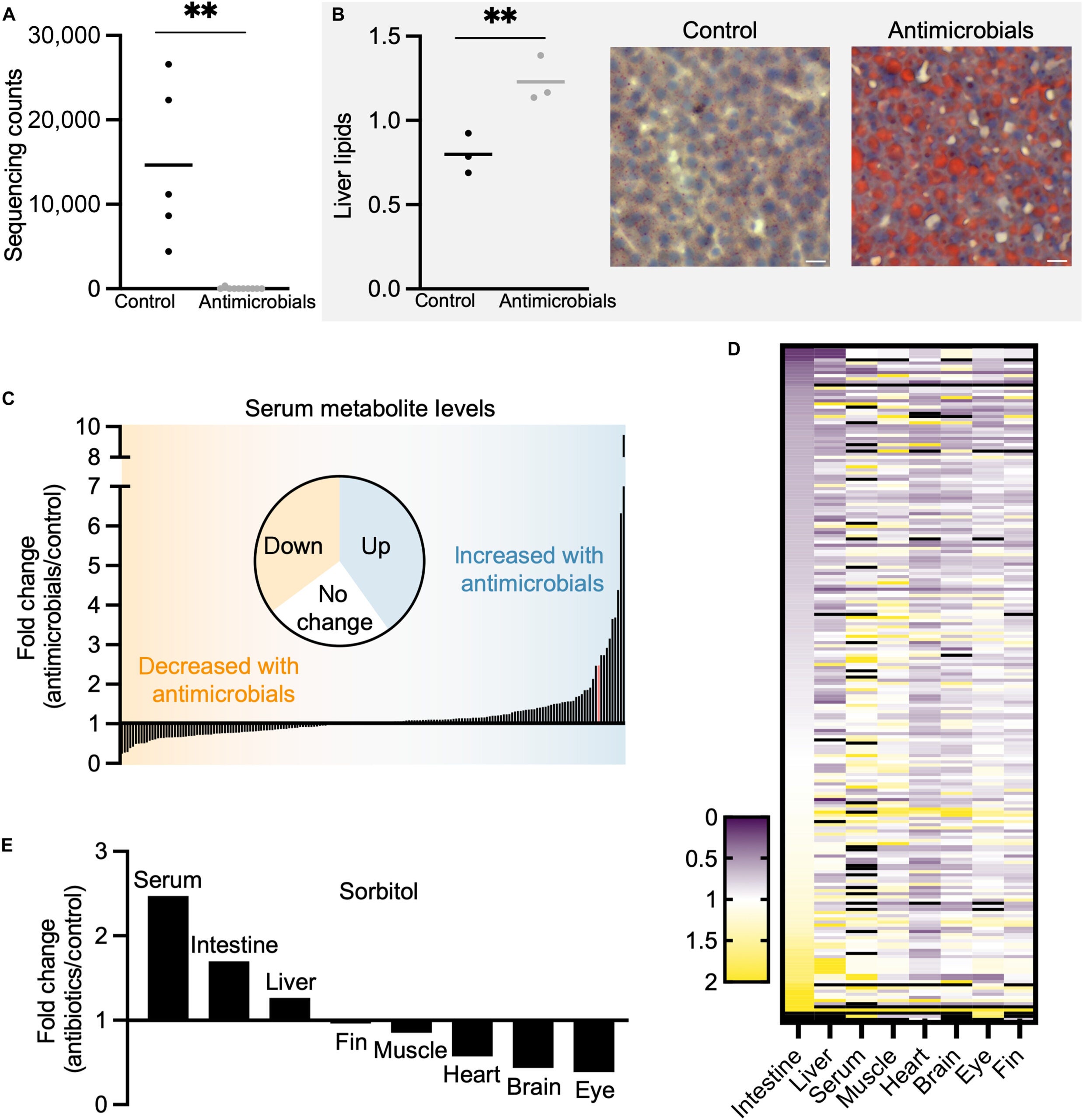

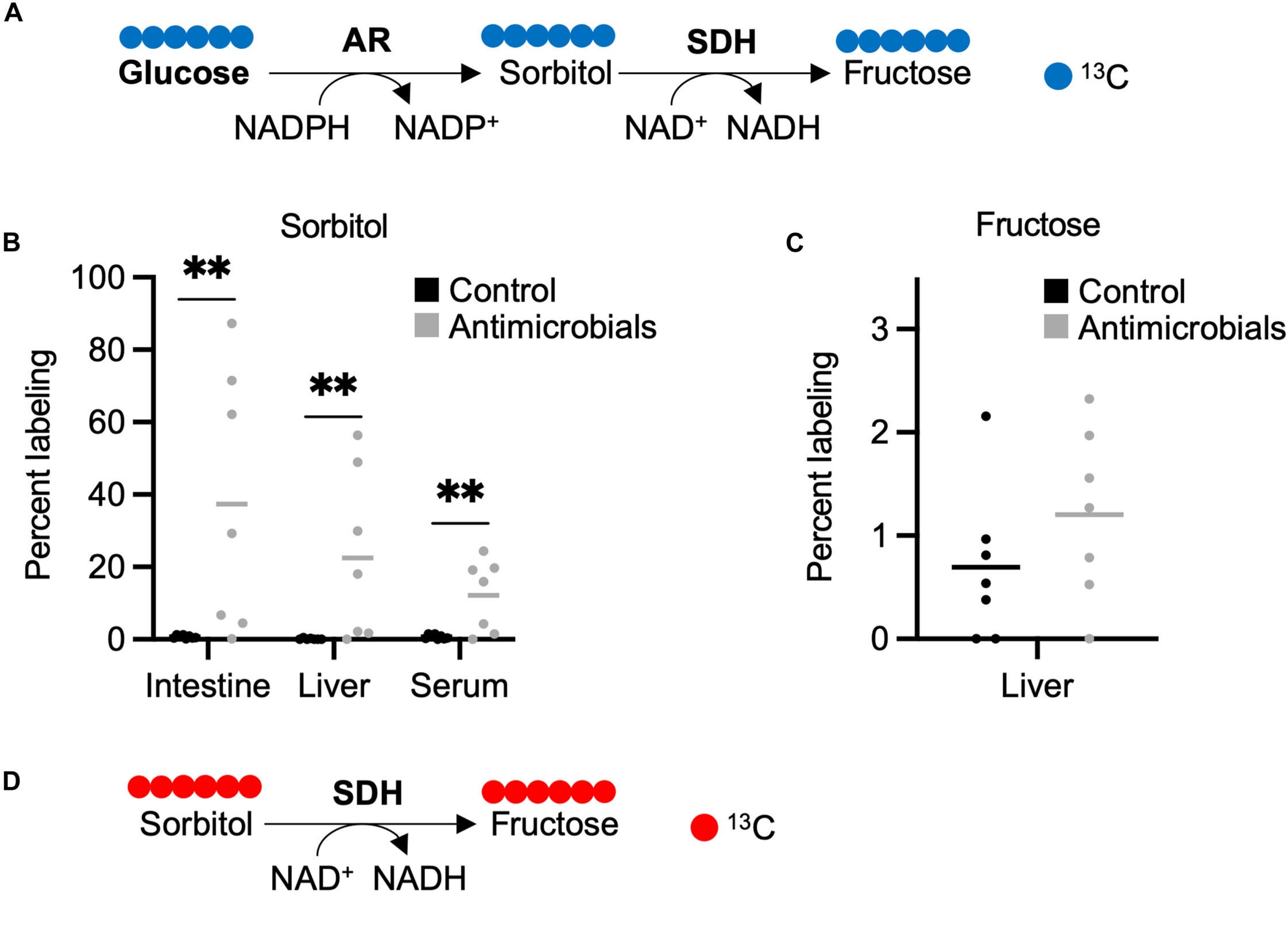

To uncover this connection, scientists turned to zebrafish, a model often used to study metabolism. They found that sorbitol enters the body through two routes. Some of it comes from food, especially sugar-free candy, gum, and certain fruits. But the body also produces sorbitol inside the intestine after meals. When glucose levels spike in the gut, an enzyme converts part of that glucose into sorbitol. This happens even in healthy people.

Under normal circumstances, friendly bacteria in the gut break down sorbitol before it travels anywhere else. Patti’s group identified strains of Aeromonas bacteria that can completely degrade sorbitol and turn it into harmless byproducts. When these bacteria are present in healthy numbers, sorbitol rarely causes trouble.

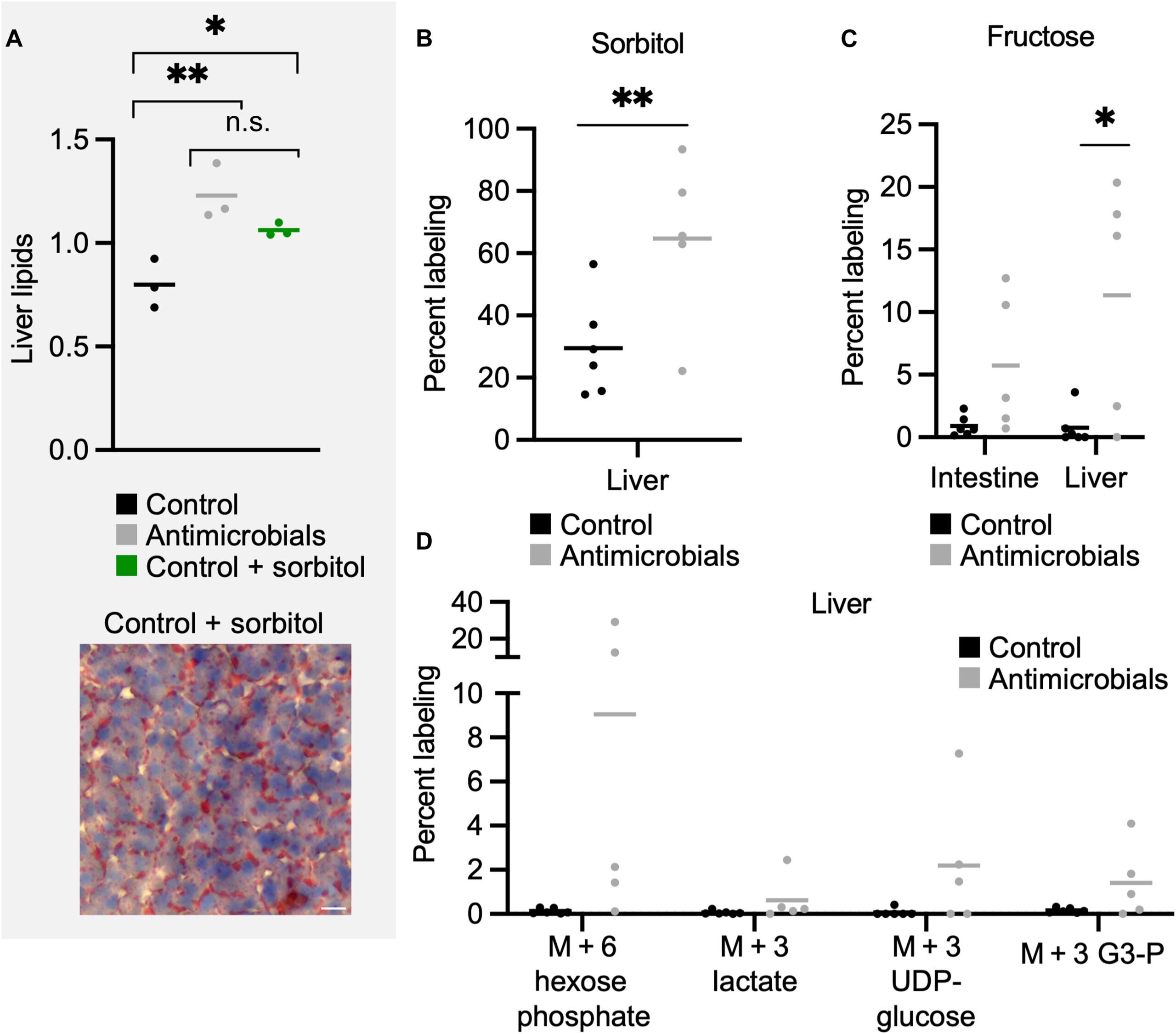

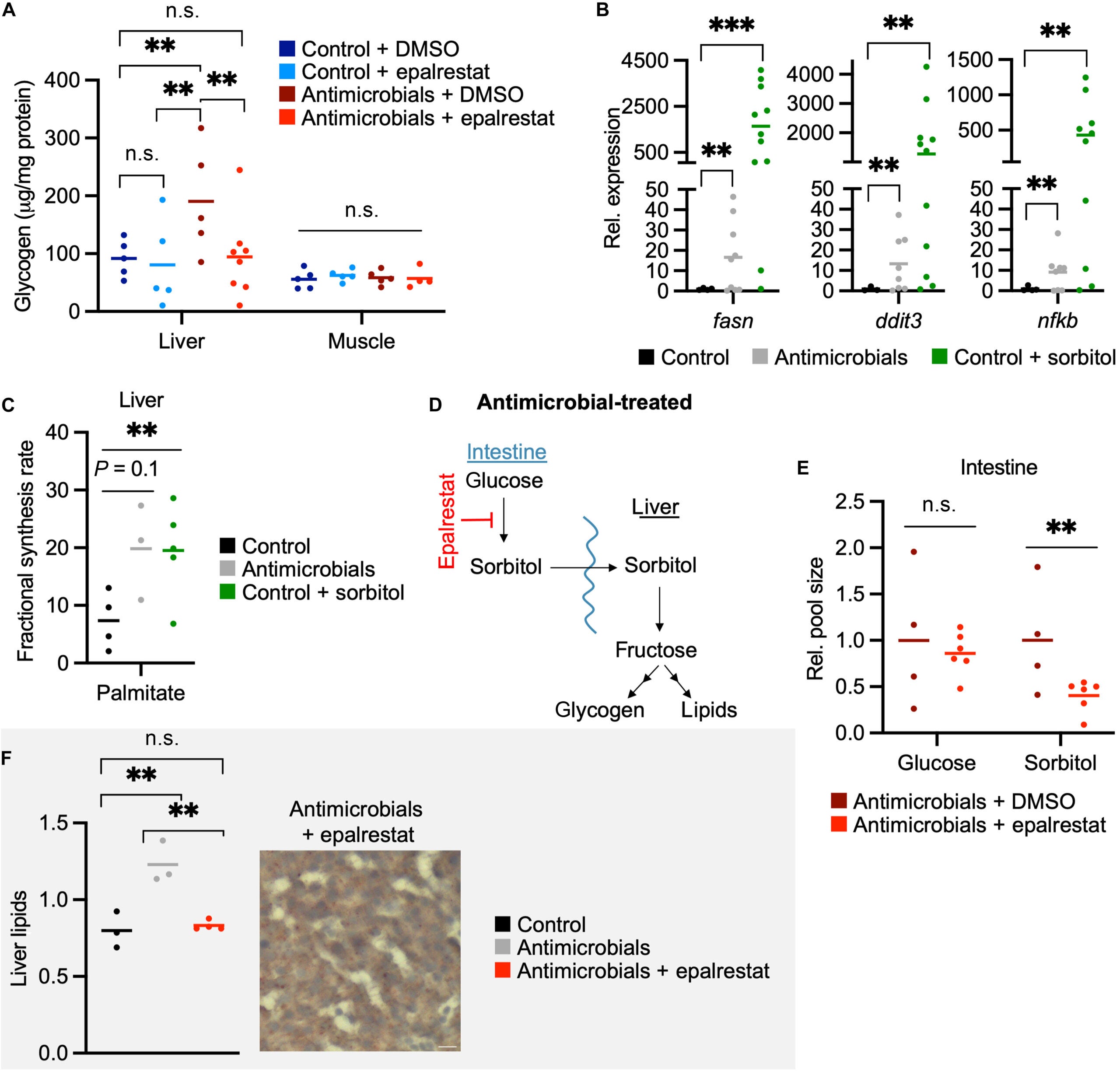

The problem begins when those bacteria are missing or overwhelmed. If sorbitol builds up faster than gut microbes can clear it, the excess travels to the liver. Once there, liver cells convert it into a form of fructose that sets off a cascade of metabolic reactions. These reactions encourage the liver to store more fat and more glycogen, two hallmarks of steatotic liver disease.

“It can be produced in the body at significant levels,” Patti said. “But if you have the right bacteria, turns out, it doesn’t matter.” Without those bacteria, the safety net collapses.

Large amounts of sorbitol are not required to trigger problems. Patti’s team observed that even typical eating patterns can nudge sorbitol production upward. When diets are heavy in glucose, sorbitol levels can climb quickly after meals. And when foods contain added sorbitol on top of that, gut bacteria may not be able to keep up.

“It’s becoming extremely complicated,” Patti said. He even learned that his own favorite protein bar contained an unexpectedly high amount of sorbitol.

The research showed that sorbitol buildup is not limited to the gut or the liver. “We do absolutely see that sorbitol given to animals ends up in tissues all over the body,” he said. That raises questions about whether other organs might also be affected.

The study revealed that the health of the gut microbiome shapes how the body handles sorbitol. In zebrafish lacking gut bacteria, steatotic liver disease developed within a week, even without high-sugar diets. When scientists restored sorbitol-degrading bacteria, the liver damage reversed.

This suggests there is no single path to liver dysfunction. Instead, diet, gut microbes, and metabolism intersect in ways that can either protect the liver or overwhelm it. Even people with healthy gut bacteria can face risks if sorbitol intake gets too high.

The message, Patti explained, is that sorbitol may not be as harmless as many believe. “There is no free lunch,” he said. The assumption that sugar substitutes are safe simply because they do not have the same calories as sugar may be too simple for a system as complex as the human body.

For people with diabetes or metabolic disorders, sugar substitutes are often a lifeline. Many rely on sorbitol-sweetened foods to avoid sharp jumps in blood glucose. But the study raises urgent questions about whether heavy use of sorbitol may shift the burden from blood sugar control to liver health. The researchers stress the importance of understanding how much sorbitol the average person can safely tolerate, and how factors such as recent antibiotic use, changes in gut bacteria, and high-glucose diets influence that threshold.

Avoiding both sugar and sweeteners is not simple. Modern foods often contain several types of added sweeteners, and ingredient labels are not always clear. Researchers believe this makes it especially important to study how alternative sweeteners behave when combined with real-world diets.

This study suggests that sorbitol may contribute to steatotic liver disease when gut microbes are missing or overloaded. It highlights the need to rethink what qualifies as a “safe” sugar substitute, especially for people who rely on sugar-free foods. The findings could shape new dietary guidelines, influence labeling standards, and encourage the development of sweeteners that do not create harmful metabolic byproducts. Long term, the work may guide efforts to strengthen gut microbiome health as a way to protect against metabolic disease.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Signaling.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Sugar substitute sorbitol linked to unexpected liver disease appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.