Tanning beds promise a quick glow, but a new study says the real cost is written deep into your skin. Researchers have found that young indoor tanners carry genetic damage in their skin cells that looks decades older than their age, and that damage includes mutations known to lead to melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer.

The research, led by scientists at UC San Francisco and Northwestern University, compares the skin of indoor tanners in their 30s and 40s with people in their 70s and 80s who never used tanning beds. The results are blunt.

“We found that tanning bed users in their 30s and 40s had even more mutations than people in the general population who were in their 70s and 80s,” said Bishal Tandukar, PhD, a UCSF postdoctoral scholar in dermatology and co first author of the study. “In other words, the skin of tanning bed users appeared decades older at the genetic level.”

Those mutations are not just abstract changes. Many of them fall in genes already linked to skin cancer. Skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States, and melanoma, while only about 1% of skin cancers, causes most of the deaths. Around 11,000 Americans die from melanoma every year, primarily from exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

UV radiation comes from sunlight, but also from artificial sources like tanning beds. As tanning culture has grown, rates of melanoma have climbed as well, especially among young women, who make up much of the tanning salon clientele.

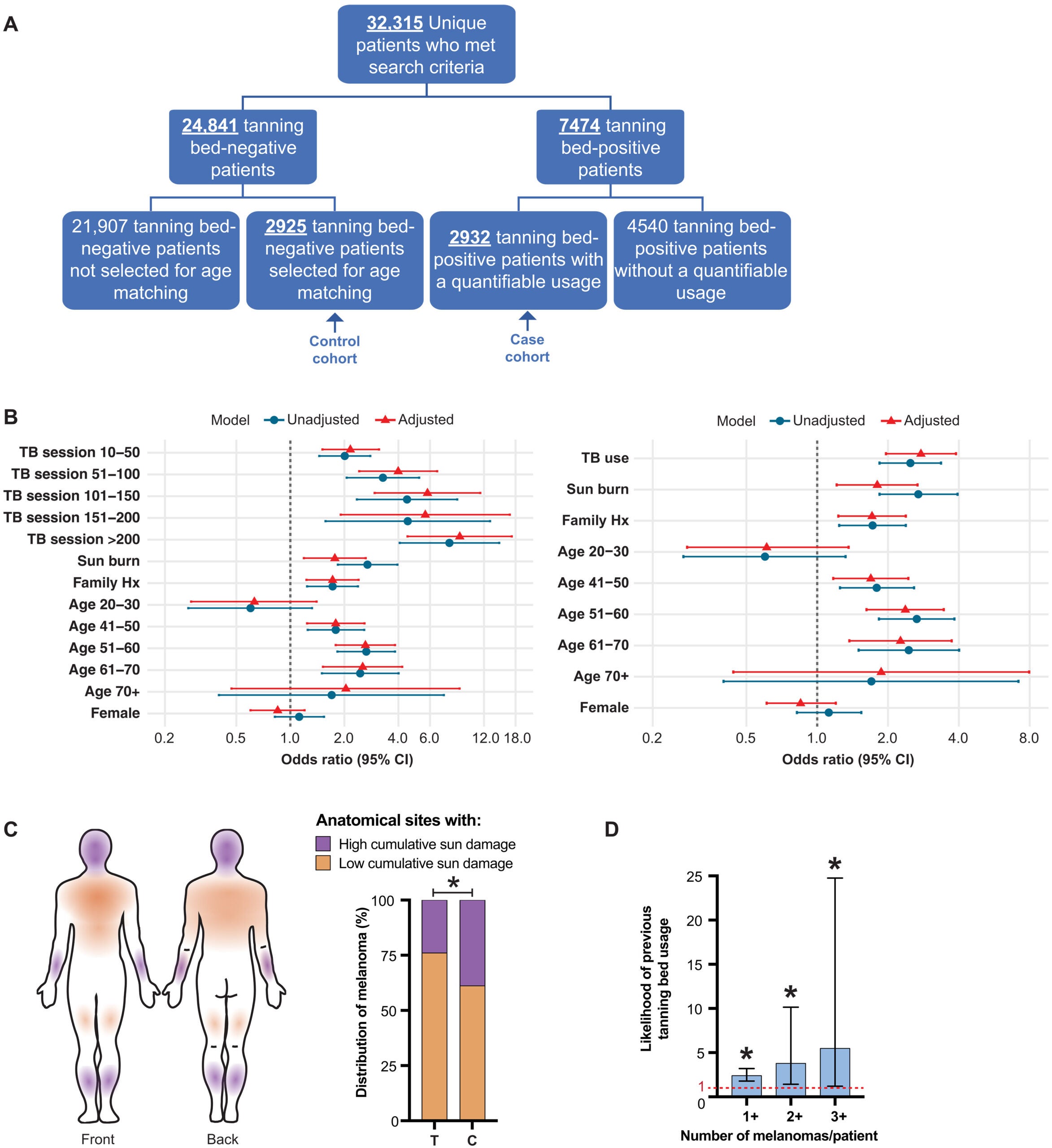

‘To move beyond broad statistics and look at real biological damage, our team took a two part approach. First, we reviewed medical records from more than 32,000 dermatology patients. Those records included details on tanning bed use, history of sunburn and family history of melanoma,” Tandukar told The Brighter Side of News.

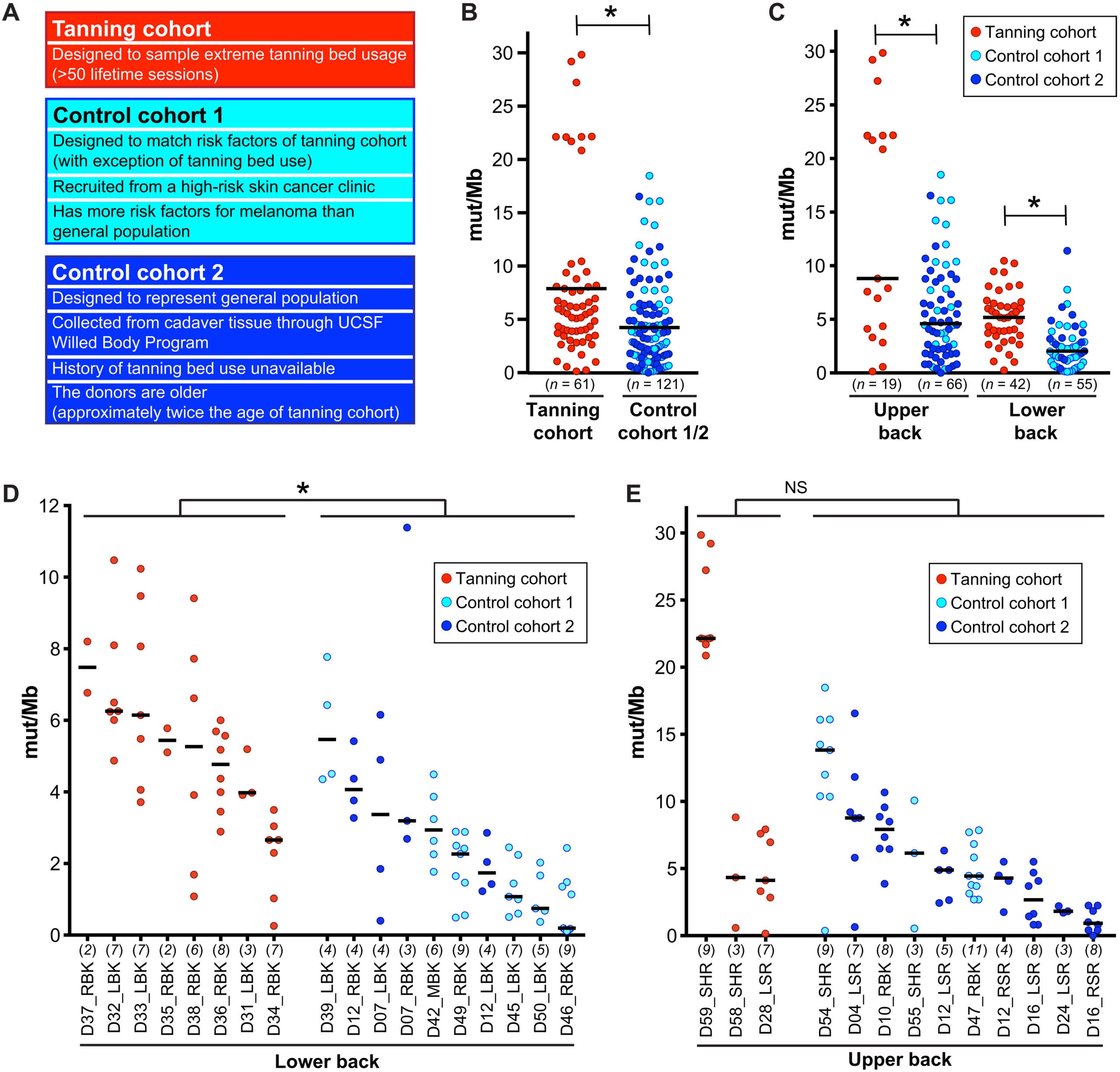

“Next, we collected skin samples from 26 donors and examined 182 individual cells under the microscope of modern genetics. By sequencing the DNA in those cells, we could count and catalog mutations in the skin’s pigment producing cells, which are the cells that can turn into melanoma,” he continued.

The pattern they found was clear. Younger adults who used tanning beds had more mutations than people twice their age who had not tanned indoors. The effect was especially strong in the lower back, an area that usually gets little sun in daily life but receives heavy exposure in tanning beds.

“The skin of tanning bed users was riddled with the seeds of cancer, cells with mutations known to lead to melanoma,” said senior author A. Hunter Shain, PhD, an associate professor in the UCSF Department of Dermatology.

On the surface, a tan can look like a sign of health. At the DNA level, it tells a different story. Each time your skin gets hit with UV radiation, small breaks and changes occur in the genetic code of your cells. Your body can repair some of this damage, but not all of it. The leftover mutations gradually pile up.

In this study, that pileup happened much faster in people who used tanning beds. By their 30s or 40s, frequent indoor tanners carried a mutation burden similar to, or worse than, people in their 70s and 80s. The genetic “age” of their skin had jumped ahead by decades.

That jump matters because cancer begins long before a tumor appears. It starts when a collection of cells pick up enough harmful mutations to break normal controls on growth. The study shows that indoor tanning pushes many of your skin cells closer to that tipping point, even in areas that rarely see the sun in normal life.

The lower back finding offers a vivid example. Most people do not walk around with that part of their body exposed to midday sun. Yet tanning beds bathe it, along with the rest of the body, in artificial UV light session after session. In the study, that area in indoor tanners carried a heavy load of mutations, while similar areas in non tanners did not.

That means indoor tanning is not just “extra sun.” It is a different pattern of exposure altogether, soaking almost your entire skin surface in radiation that your daily routine would never deliver. Your cells cannot tell whether UV light comes from a beach day or a tanning booth. They only know they have been damaged.

“We cannot reverse a mutation once it occurs, so it is essential to limit how many mutations accumulate in the first place,” Shain said, whose laboratory focuses on the biology of skin cancer. “One of the simplest ways to do that is to avoid exposure to artificial UV radiation.”

Many countries have responded to this kind of evidence with strict limits or near bans on tanning beds. The World Health Organization classifies tanning devices as a group 1 carcinogen, the same category as tobacco smoke and asbestos. Yet tanning beds remain legal and widely used in the United States.

Part of the problem is that you cannot feel mutations as they happen. A session may leave you warm and relaxed. The damage is quiet, living on inside the DNA of your skin cells. This study makes that hidden harm visible at a fine scale, and ties it directly to known cancer driving changes.

If you have ever thought of indoor tanning as a controlled alternative to sun exposure, the findings suggest that belief is dangerously out of date. The genetic footprints in the skin of frequent tanners look less like a gentle shortcut to a tan and more like a fast track toward early, unnecessary risk.

These results give doctors and public health officials a powerful, concrete way to talk about tanning beds. Instead of relying only on long term cancer statistics, they can now point to direct genetic evidence that indoor tanning loads young skin with mutations usually seen much later in life. That may help shape policy debates on restricting or banning tanning beds, especially for minors, and may strengthen warnings on devices and in salons.

For you as an individual, the message is personal. Every indoor tanning session adds to a bank of DNA damage that your body cannot erase. Choosing to avoid tanning beds reduces how quickly harmful mutations build up and lowers your lifetime risk of melanoma.

The study also highlights body areas you might not think about, such as your lower back, as vulnerable to intense artificial UV exposure.

Over time, the same approach used here could inform better screening strategies, guiding dermatologists to pay closer attention to regions that tanning beds hit hardest.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Tanning beds turn young skin genetically old, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.