Memorizing seven continents feels settled, like learning the alphabet. A new study argues the ground rules are less tidy. The work comes from the University of Derby, led by Dr. Jordan Phethean. His team says Europe and North America may not be as cleanly separated as most maps suggest.

The focus is the North Atlantic, where the Mid-Atlantic Ridge marks active stretching. Many textbooks treat that ridge as the scar of a breakup that happened long ago. Phethean’s group argues the separation is not finished. In their framing, the North American and Eurasian plates are still connected in ways that matter.

“The North American and Eurasian tectonic plates have not yet actually broken apart, as is traditionally thought to have happened 52 million years ago,” Dr. Phethean said.

Iceland sits at the center of the debate. The island rises along the ridge, and it has long been tied to the idea of a deep mantle plume. In older explanations, Iceland helped confirm that the plates split, then magma filled the gap. The new study flips that emphasis. It treats Iceland and nearby undersea ridges as clues that fragments from both sides remain stitched into a broader structure.

Phethean and colleagues argue Iceland and the Greenland Iceland Faroes Ridge, often shortened to GIFR, include geological pieces linked to both Europe and North America. They propose a new label for the setting: a “Rifted Oceanic Magmatic Plateau” (ROMP). The point is not that continents are about to merge. The point is that the boundary may be messier than a simple ocean divide.

Phethean describes the discovery as the Earth Science equivalent of finding the Lost City of Atlantis because his team uncovered “fragments of lost continent submerged beneath the sea and kilometers of thin lava flows.”

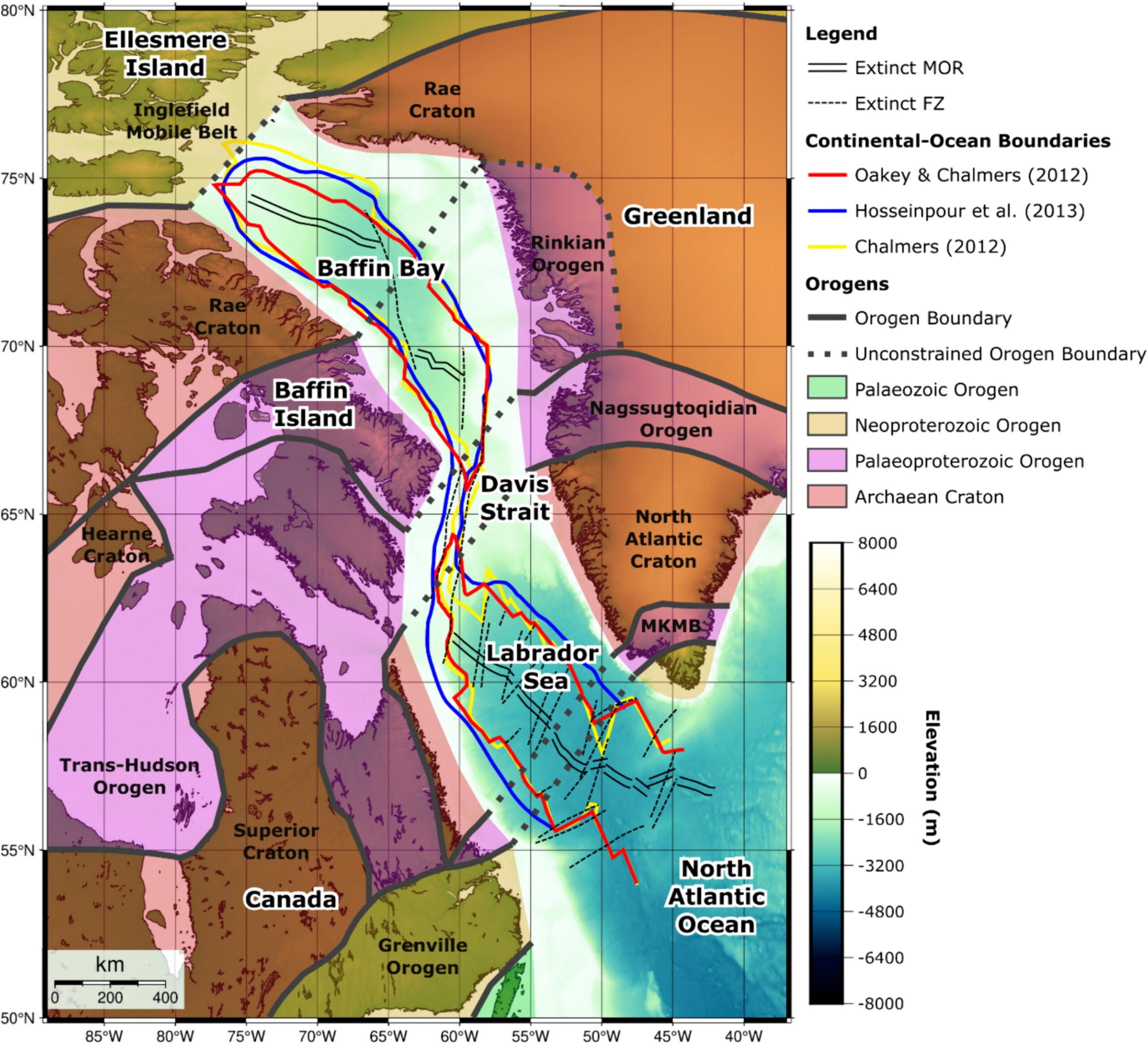

To show how incomplete breakups can look, the researchers point to another region where the crust seems stuck between outcomes. That is the Davis Strait, a shallow seaway linking the Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay between Canada and Greenland.

In earlier work discussed in the study, the team described a hidden “proto-microcontinent” beneath the Davis Strait. A microcontinent is a chunk of continental crust that starts to split away during rifting, then ends up isolated and surrounded by oceanic crust. A proto-microcontinent sits one step earlier. It begins to peel away but never fully breaks free.

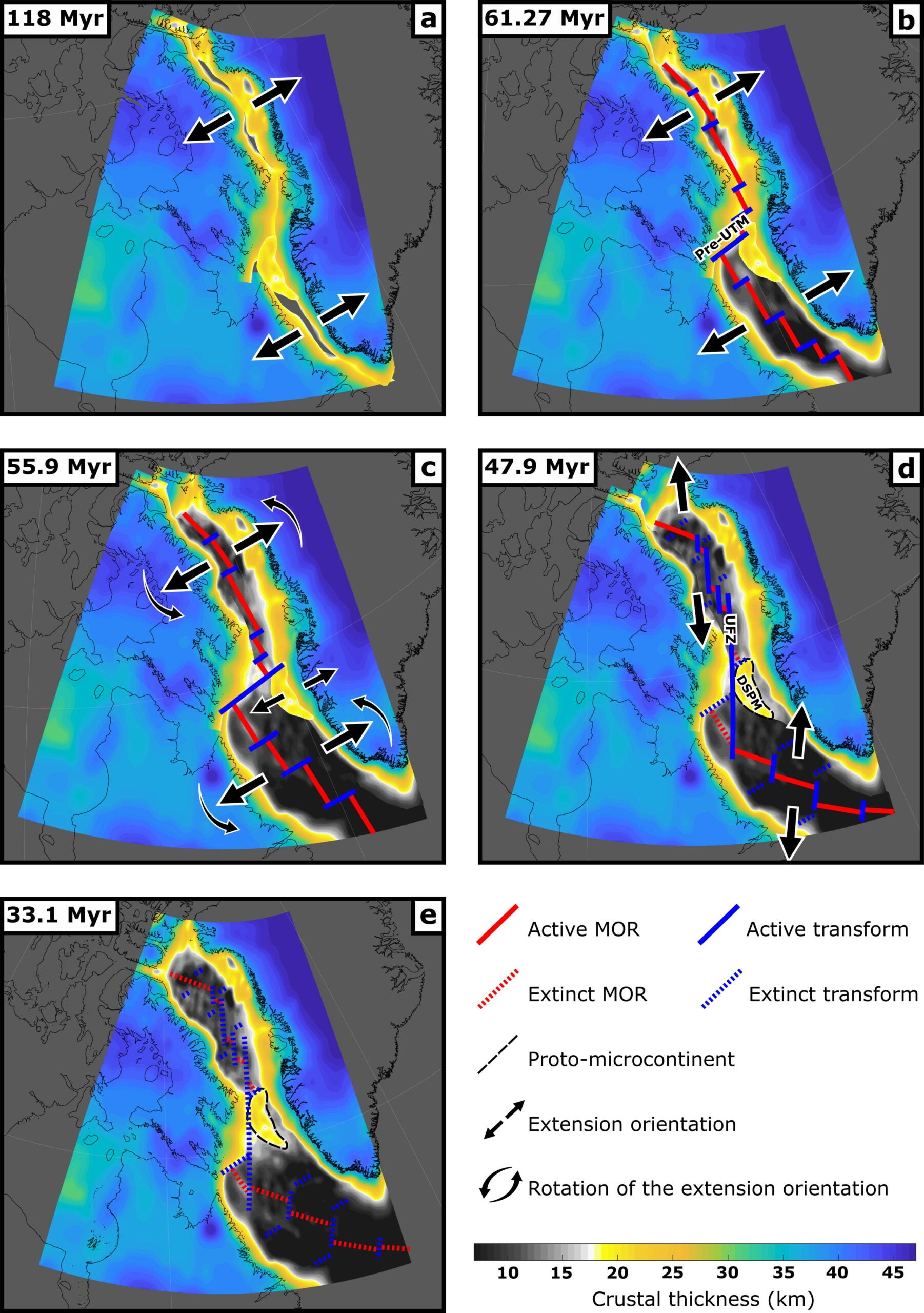

This matters because the Northwest Atlantic did not open in one smooth motion. Stretching began as early as the Late Triassic, around 223 million years ago. The region then went through long phases of pulling apart and sinking. Later, seafloor spreading began in the Labrador Sea, though scientists still debate the exact start date. Spreading later reached Baffin Bay during chron 26, around 58.9 million years ago.

The Davis Strait stands out because it does not look like a normal strip of oceanic crust. Parts of its crust reach about 30 kilometers thick. Fully developed oceanic crust is usually far thinner. For decades, researchers have argued about what that thickness means. Some explanations leaned on extra volcanic rock. Others suggested continental crust remained there, mixed with magma.

The new analysis leans toward the second idea. It treats the Davis Strait as a transfer zone. In simple terms, it links two spreading systems, without becoming a true spreading center itself. That framing sets up the team’s core claim. A thick crustal block in the strait looks like stretched continental crust, not just a volcanic pile.

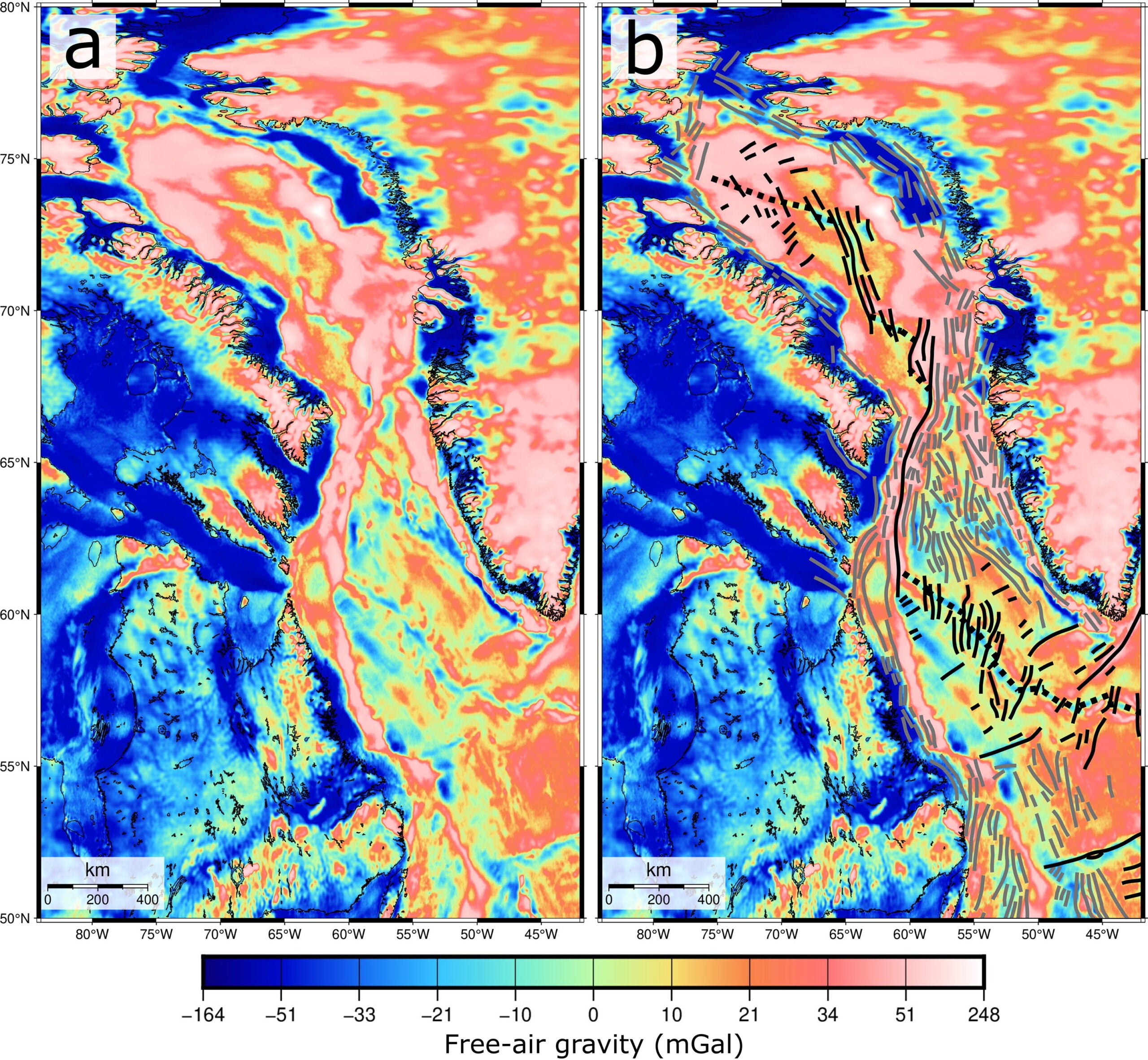

To rebuild what happened, the study combines several kinds of evidence. One major tool is gravity data, which can reveal buried structures because denser rock pulls slightly harder. The team used the Sandwell and Smith gravity model (version 31.1), which the study notes has about 2 mGal accuracy after satellite-based improvements.

“Our research team filtered the data to highlight features on the scale of plate boundaries. Short wavelengths under 50 kilometers and long wavelengths over 100 kilometers were removed. That helps separate shallow seafloor noise and deep mantle signals from ridge and fracture-zone patterns,” Phethean told The Brighter Side of News.

“We then sharpened line-like features by testing many directions, in 10-degree steps. This helped us pick out old ridge segments and fracture zones even when thick sediment hides the seafloor shape. Sediment can mask topography, but density contrasts can still show up in gravity,” he continued.

Gravity patterns alone cannot date events, so the study also reinterprets seismic reflection lines offshore West Greenland. It draws on information tied to wells, including Ikermiut-1 and Quelleq-1, to judge when certain faults stopped cutting young layers.

The team also updates a crustal thickness model, adding new onshore receiver-function results and blending them with offshore estimates. The study says this sharpened thickness gradients near the continental shelf. That detail matters because the argument depends on where thick crust ends and thin crust begins.

The mapped results identify extinct ridge segments in the Labrador Sea and Baffin Bay, but none in the Davis Strait. They also show two main sets of fracture zones. One set trends roughly north to south and aligns with Eocene activity. Another trends northeast to southwest and aligns with earlier Paleocene activity.

The crustal thickness map is the heart of the proto-microcontinent claim. It shows a thick block in the Davis Strait, around 19 to 24 kilometers, surrounded by thinner corridors around 15 to 17 kilometers. Those thinner zones separate the block from Greenland and from Baffin Island.

The study links this thick block to the Davis Strait High. It is described as relatively thick continental crust, over 20 kilometers in places, with gravity patterns trending NNE to SSW. In the team’s view, that is easier to explain as stretched continental material than as a purely volcanic feature.

The paper also proposes a two-transform story for the region. The better-known Ungava Fracture Zone, or UFZ, became a major transform fault later. But the team argues that an earlier transform margin existed first. They call it the Pre-Ungava Transform Margin, or Pre-UTM.

In their reconstruction, early spreading in the Labrador Sea and later spreading in Baffin Bay required a transform link because the ridge segments were offset. The Pre-UTM served that role. Later, plate motion changes compressed and sheared that older boundary. The UFZ then developed in a more north to south direction, cutting across and replacing the older transform.

The timeline in the study ties this to shifts in motion. Major extension begins around 120 million years ago. By about 61 million years ago, seafloor spreading starts in the Labrador Sea, while the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay keep stretching. By about 59 million years ago, spreading reaches Baffin Bay, and the transform link through the Davis Strait becomes fully developed.

Around 56 million years ago, the study says tectonic reorganization rotates the spreading system toward a north to south direction. That change lines up with reverse faults and folds in the northeast Davis Strait. It also lines up with renewed stretching along the West Greenland margin. In this model, that renewed stretching begins to peel off the proto-microcontinent.

By about 48 million years ago, the UFZ becomes the main transform boundary. The Davis Strait then stops short of full breakup. Seafloor spreading ends later, by about 33 million years ago, as Greenland’s rotation contributes to collision farther north.

Phethean tied the broader lesson to how continents behave over time. He noted that “rifting and microcontinent formation are ongoing phenomena” that can help scientists anticipate Earth’s distant future and hunt for useful resources.

If the study’s interpretation holds up, it changes how researchers describe boundaries in places where continents are still pulling apart. That could improve plate-motion models used to reconstruct past climates and oceans, since seaways often open and close with tectonic change. It may also sharpen estimates of where continental crust continues beneath deep water, which matters for understanding earthquake risk along old margins.

The work could also guide future resource research. Continental crust and volcanic crust can host different mineral systems. Mapping where fragments of continental material remain may help geologists target areas for further study.

The team also points to next steps, including tests on Iceland’s volcanic rocks, computer simulations, and plate-tectonic modeling, to check whether older continental material truly sits beneath lava-rich regions.

Research findings are available online in the journal Gondwana Research.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Tectonic research finds that Earth has six continents not seven appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.