By James Acaster’s calculations, he gets heckled more than the average comedian. In his new HBO special Hecklers Welcome, out November 23, he recalls being heckled so relentlessly during his international stand-up tour in 2019 — often before he could even get to his first punch line onstage — that he was miserable while playing the biggest venues of his career. The special, in which hecklers are given free rein to interrupt the show, is the 39-year-old’s attempt to explore his prickly relationship with his audience once and for all. It’s a struggle that has undergirded nearly all of his material as he’s grown into one of the U.K.’s most successful comedians (and U.S. comedy imports) over the past decade.

Acaster burst onto the U.K. comedy scene in the late aughts as a critical darling, and he was nominated for the famed Best Comedy Show award at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe a record-breaking five times between 2012 and 2016. He followed this up in 2018 with Repertoire, an ambitious, four-part Netflix special culled from his Edinburgh shows featuring a virtuosic blend of character-based fictions, gangly slapstick, precise observational comedy, and biting political commentary. At various points, he’s an undercover cop, juror in a criminal trial, proprietor of a fraudulent honey business, and head of a conga line crumbling under the pressures of leadership, and he sneaks deceptively deep personal revelations into these elaborate, silly narratives.

Parallel to this, he built a rabid following thanks to his fan-favorite appearances on popular U.K. panel and competition shows like Mock the Week, Would I Lie to You?, and Taskmaster, where he often played up the schtickier aspects of his whimsical comic persona. Soon, fans of Acaster’s television appearances began funneling into his live gigs, and a vocal minority was less interested in his intricately crafted stand-up routines than glimpsing the oddball they’d seen goofing around on TV in person. A similar thing happened after Acaster launched his hit food-themed podcast, Off Menu, with co-host Ed Gamble in 2018; it wasn’t long before his stand-up shows were routinely interrupted by hecklers shouting out his podcast catchphrase, “Poppadoms or bread?”

Acaster’s frustrations with that emerging dynamic informed the writing of his acclaimed 2020 special, Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999, in which he dropped character onstage for the first time since he was an open-mic act and told true stories from his life. One now-famous anecdote from the special saw him unpack his 2019 appearance on The Great British Bake Off, when, while sleep deprived and in genuine crisis, he explained the process of making one of his dishes by saying, “Started making it. Had a breakdown. Bon appétit.” The moment was played for laughs on TV, and the audience at home turned it into a viral meme. “Audiences are the worst part of this job,” he says at one point in the special. “Night after night, I’m the one out of everyone in the room who knows the most about comedy, and I’ve got to win your approval.”

In Hecklers Welcome, Acaster takes a step back and examines his role in perpetuating this strained dynamic. Over the pandemic, he realized that his unhealthy reaction to audience interruptions was rooted in the intense pressures he’d been putting on himself and the baggage he was bringing to the stage as a performer. He briefly considered quitting stand-up, but then he created the conceit of Hecklers Welcome as a last-ditch effort to try to manifest these breakthroughs onstage, too. He approaches his hecklers in the special with kindness, but he also performs a more intimate, less tightly wound show, and it’s clear he’s no longer living and dying on the success of each punch line. It’s lighter on the high energy comedy audiences once gravitated to him for, but he’s happy to live with the tradeoff. “The main thing with this show was, If I don’t deal with this issue that’s making me so unhappy at work, I’m not going to be able to do any show after this,” he says. “What I wanted from it is that it would enable me to just be a comedian again.”

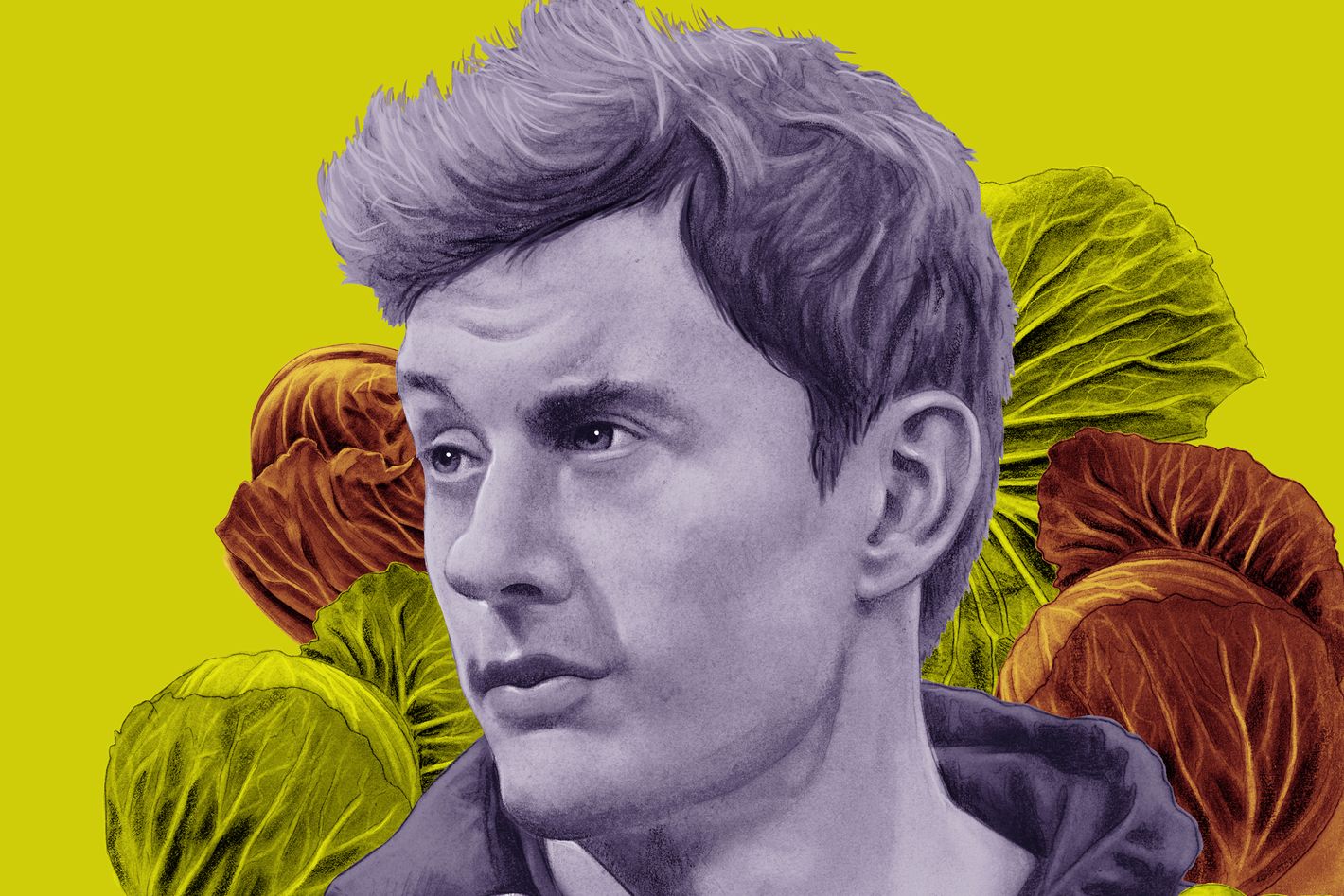

In 2018, I went to a show you performed at the Just for Laughs festival in Toronto, and toward the end of it, an audience member stood up and handed you a head of cabbage. How often was that happening to you after you told your story about being “cabbaged” on Would I Lie to You?

That’s something that I don’t remember, because it’s so common. On this last tour, someone threw one from a balcony, and it landed on the stage and exploded. People would usually put them onstage before I went on, and if my tour manager saw that, he would get rid of them. On the last tour, someone had their cabbage removed, and then — not thinking I had anything to do with it — they went up to the venue security and said, “Excuse me, that man took my cabbage offstage. Could you please inform him that he’s just ruined a joke and he should leave it there?”

It’s such a weird story. It doesn’t work as stand-up, but it didn’t work if I ignored it either, because the audience would be thinking, There’s a cabbage onstage. Why is he ignoring that? I found the only way of being funny with it would be to walk onstage and kick the cabbage into the opposite wings as hard as I could, so it had some height on it. That would go down better — until I did it in New York. I kicked the cabbage offstage, and a woman in the front row stood up, burst into tears, and said that she had got that “especially for me,” and then she stormed out of the show.

The premise of your new special is that you can’t get mad at people for heckling. In practice, did creating that rule keep you from getting angry internally?

There were definitely people heckling who would still be jerks, but the aim wasn’t that I wouldn’t get annoyed anymore, because none of us can go, I’m gonna make sure I’ll never be annoyed at work again. But not crossing the line of getting annoyed at them was really important to me. And that’s not saying no comic should do that. I just don’t think it suits my persona or my show. There were a few heckles where I’d be like, That was quite an obnoxious heckle, but what I found was if I don’t get annoyed at those people out loud, the audience, nine times out of ten, will do it for me.

You released an album version of Hecklers Welcome from a show you recorded in your hometown, Kettering, where it went completely off the rails. How many stops on the tour were like that, where you couldn’t get through your material at all?

Maybe 10 or 15 percent. You do all your work-in-progress shows, and they’re usually to really devoted comedy fans, so I wasn’t really getting heckled loads. I remember on night one of the tour in Cardiff, Wales, thinking, Maybe I’ve made a huge mistake here. I’m about to walk out, and they could just heckle me for the whole show. Then they didn’t heckle me at all; they just watched the show. Very few just became a mush, which is why I was really glad that the Kettering one that we recorded for the vinyl was so heckle-y, and did fall apart. I was happy that I had a completely different version of it on audio that I could release so people could see how differently it could go. But there were a few times … I think Edinburgh was the one where we just couldn’t get it back on track. I congratulated the audience on winning the gig.

Did you feel the theme of the show was undercut on nights when there was no heckling?

Yeah. Because it’s called Hecklers Welcome, even people who don’t like hecklers are a bit disappointed if there isn’t a heckler. And if there is a heckler, you end up showing rather than telling, and that’s always better. If you deal with it the way that you want to deal with it, you’re demonstrating some change in yourself, and they can see, Oh, that’s what he means in terms of how he’s dealing with hecklers now. When they hear a heckle, they might think of their own put-down or slam that’s quite vicious, and they might feel that the heckler deserves that. So then to see that not happen gets across what the show is about way better than any of my material could.

How many of the heckles were creative as opposed to people just shouting your Off Menu podcast catchphrase “Poppadoms or bread?” at you?

50-50, maybe. Pretty much every show there was a “Poppadoms or bread?” heckle. Obviously, the best heckles were ones where people, in the moment, responded to the show, and would genuinely have a thought or a feeling about something I’ve just said — maybe a funny one — and they would chuck that in. The ones that people worked on in the car on the way to the show were never very funny, and you could tell the audience felt like the person had tried a bit too hard to come up with something.

It became funny whenever anyone shouted “Poppadoms or bread?” because in their voice, I could feel how certain they were that that was original, and that no one would have done that to me. It was one of those things where I had to have a word with myself and be like, You can’t be annoyed at these people. You shouted it every single episode. You know what happens with catchphrases. More and more, I would try to react to them genuinely. I’d choose one of the other — poppadoms or bread — and I would say a specific place that I’d had it in that city to shout out a local restaurant.

Did you have a favorite heckle from the tour?

There were so many good ones. There was a guy who followed me around on tour and would heckle me that I was better at the last show that he saw me at. He saw me in Gothenburg, Vancouver, and Scotland, so he was traveling the world to see me. The first two times, I remember thinking in my head, This guy’s flying to see me and his heckle is critical of me? But then, by the third time, I was like, This is funny, and we got to know him. We had a 20-minute-long conversation with him in Vancouver and learned all about his life, the complicated relationship he’s in, and his job. That was really satisfying for me to have that personal payoff to this peculiar heckler.

At some point between when you started touring Hecklers Welcome and now, it became a trend for comedians to post crowd-work clips on social media. How does it feel to be releasing a special with crowd work in it at this moment?

Because I’ve not been on social media, I forget that’s a thing. I haven’t really seen many of them, so I don’t know what form they usually take. I think that, in the context of the show, it will feel different to people than those videos do. We only kept heckles in that served the narrative of the show. We cut out ones that were just fun — maybe those will see the light of day one day, and that will be a bit more in the vein of what you’re talking about. But if I was to ever release those videos, the tagline definitely would not be “Comedian Destroys Heckler.” Sometimes, it would be “Heckler Destroys Comedian,” which I personally find more interesting.

Although I do get the catharsis behind it. When I started stand-up, half the reason I would go in on hecklers so hard is because I’d worked shitty jobs before stand-up, and I couldn’t say anything to the customers when they were incredibly rude or disrespectful to me. And then suddenly I was able to do it, and it was great.

A lot of the stories in the special and the stories you tell in your memoir, Classic Scrapes, point to a core desire you’ve had since childhood to get onstage and perform, even after having a bunch of negative experiences doing so. What do you attribute that to?

I’ve tried to figure it out, and I don’t talk about it in the special, because I don’t think I’ve landed on an answer yet. But I try to mention all the things I think it might be. I mention going to church all the time, and I think that as a kid, I was essentially going to a gig every week, and being in an audience where the gig never goes badly. I never saw someone die on their ass in church. It was a bit of a hippie church, so I was watching rock bands, and they did comedy sketches. That was the first time I saw live comedy. It was my favorite part of going there each Sunday. The drummer, in particular, was the person who taught me the drums in the end. A lot of people who were brought up religious will talk about this: Even if you’re not religious anymore, and I’m not, you remember that feeling of being part of a big congregation who are celebrating, and there’s so much joy in the room. You want to be a part of that as much as possible.

The funny people who got up and made us all laugh at church were my favorite people at that church. They became my first heroes, in a way. I remember being taken away to Sunday school during one of the services, and we had to write profiles of ourselves to go on the wall, like “These are the kids of the church!” One of the categories we had to fill out was “Hero.” All the kids wrote “Jesus.” It didn’t even enter my mind. I was the only kid who wrote “Robin Williams.”

There’s a part of the special where you pivot from talking about what it’s like to be a performer to talking about what it’s like to be a member of an audience. How did that part of the show develop?

That was something I felt was really important, because in the past, when I’ve acted out onstage and taken things out on the audience, I never came offstage and thought, Yeah, I was right. Fuck them. They deserved that. I’ve never watched a performance while sitting in the audience and thought, What the hell is wrong with this audience? If it’s not going well, it’s like, Yeah, this room feels a bit stale, and this news story just came out before the show, and the lights aren’t really working, and that’s putting us off. When you see a performer meet the audience with that empathy, it’s so much nicer when you’re in the crowd.

I didn’t want to make the show all about me, because it’s not. It’s about my relationship with the audience, so it’s just as much about them. When I single someone out as a heckler, they’re in the same position that I’m in. I felt like it would be very ignorant of me not to acknowledge that, and as soon as that became a part of the show, it felt a lot more complete.

In the intro of Classic Scrapes, you write that when you first started stand-up, you had a strict rule that everything you said onstage had to be true, but that the audience didn’t like it, so you switched to writing shows that were completely fictional. Then, when you were performing fictional shows, you often talked about how it would confuse audiences who wanted you to speak from your own perspective onstage. Now you’re telling true stories onstage, and if the album version of Hecklers Welcome is any indication, people are yelling out and asking you to perform things from Repertoire like the “Kettering Town FC” song. How do you approach the idea of meeting audience expectations?

You know that what you shouldn’t do — and this is probably true for anyone doing anything creative — is exactly what they want, because actually, they don’t want that. They might think that they do, but if you just go, Here is exactly what you had in your head when you left the house to come see me today, they won’t be surprised. I really would like for the show to stick with them a bit and to grow and evolve as a comic. At the same time, I don’t want to do a show where they sit there going, What the fuck is this?

I can only really write the thing that I’m in the mood for. I tried with the last show I did before this, Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999. That was my first time talking about my real life since I was an open spot — in a more real way than I’d ever done before — and there were definitely people turning up with their expectations of, I saw his Netflix shows. He’s going to pretend to be a cop or do something silly as a ruse for the show. I felt that when I was doing the work-in-progress shows, so I tried to do that at one of the shows, and it really didn’t work. I felt like they could sense that I was trying to do something that was no longer me. What they actually want is for you to be authentically where you are as a performer and as a comedian.

They might shout out stuff like, “Do the ‘Kettering Town FC’ song!”, and I think there were two times where I did it. But it was on my terms as much as it was on theirs. I had to reframe that for myself as well: They are shouting those things to let you know they love this other thing you did. You’re extremely lucky that they loved that other thing.

If you could conceive of a version of stand-up where there was no audience, what would yours look like?

When Bo Burnham did Inside, I think every stand-up had that thought of, Oh fuck, he’s done the thing that a lot of us have been thinking about throughout our careers of, “Wouldn’t it be great if I could do this without them here?” But then you are like, At what point is that not stand-up anymore? I love that special. I think it’s such an incredible achievement and will be remembered for generations. It’s such an amazing time capsule, and it was the perfect thing to do during lockdown. But in many ways, it’s the first-ever YouTuber comedy special. That was his origin, and he utilized that, and that’s what I thought was so amazing about it.

I think the answer I’ve landed on — and someone will do this at some point — is the other way around: There’s no comedian, but there’s an audience. So you go the ABBA Voyage route of having a hologram. I went to see ABBA Voyage and I got a jacket there, and originally in the show, I would wear it onstage and not reference it. Someone will do it one day, and I’ll be very jealous of that person if I’m not the one who’s done it. I probably won’t be, because the admin alone seems like an absolute fucking nightmare. But you’d be able to do multiple shows a day sitting at home somewhere else and get on with your life. That sounds pretty, pretty sweet.

Now that you’ve done stand-up out of character as a less heightened James Acaster, do you think you can go back to doing Repertoire-style comedy onstage?

I hope that no door is ever completely closed. With this last tour, it ended up being true stories out of necessity, because it wouldn’t have made sense if I was trying to deal with my relationship with the audience and not talk about my real life. But the thing with this show was, If I don’t deal with this issue that’s making me so unhappy at work, I’m not going to be able to do any show after this, because it’s just going to be like this forever. It was unsustainable going on each tour, hitting a point of not wanting to go onstage each night, sabotaging it, coming off feeling guilty, and doing that over and over — knowing that I’d worked so hard on the show, I loved stand-up, and I wanted everyone there to have a great time.

The main thing with this tour was, This is the big one that you’ve been ignoring for ages. Learning how to write stand-up, learning how to perform, developing a persona: You prioritized all of those things at one point. But now you have to prioritize your reaction to the audience. What I wanted from it is that it would enable me to do the next show and just be a comedian again. We’ll see how much I end up talking about my real life and how much I end up not doing that. The way I’m feeling at the minute — and you could be interviewing me in five years time, being like, “You said this in 2024, but then you did this” — is like doing a show that’s completely stripped-down stand-up, just to prove to myself that I can do it. That’s the end product of this tour: I can get up and be silly again.

There’s a clip of yours from Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999 where you mock “edgy comedians” that often goes viral whenever a comedian who falls under that banner releases a special. Does it make you uncomfortable to have an audience place you on a moral pedestal like that?

Again, not being on social media really helps with that, because it means I don’t see a lot of the discourse around that. I’m aware that it happens, but the main thing that feels weird about it is that, a lot of the time, it’s an edgy comic punching down on another group, and I’m benefiting from that by my clip going viral. Even though I’m not in control of that, it’s a very conflicting feeling. The people who are sharing that clip have connected with it, and that’s nice, but you don’t get to be like, “Yippee!” I just have to let it go and let it have its own life, just like any routine. I know so many creative people say, “It doesn’t belong to you anymore once you’ve done it,” but that is the truth.

Because you’ve done a fair amount of political material like this, do you think there’s a portion of your audience now who shows up to your gigs who are less interested in the comedy you’re doing than the points you’re making?

I haven’t had that, because I haven’t made it my whole thing. On the Cold Lasagne tour, anytime I bought up Brexit, which was in the first five minutes of the show, it made it hard. This is one of the things that people on the other side of things with comedy don’t understand: They think if we’re left-wing, we’re going onstage and doing our left-wing political material for applause. My experience of it is that my last show would have been a lot easier if I wasn’t talking about Brexit, and if I wasn’t doing that routine that keeps going viral. I got a good response when I filmed the show in London, so that’s what people see, but that wasn’t always the case. It was to the point where it affected the house rules for the Hecklers Welcome show, and I had to say “No hate speech,” because that had happened on previous tours.

In Cold Lasagne, you told your now-famous story about appearing on The Great British Bake Off while having a mental breakdown and then becoming a meme. Do you feel like, because of your appearances on shows like that, there’s still part of your audience that sees you more as a purpose-made vessel for comedy rather than as a human being?

90% of the audience has the right attitude and are turning up to see a comedian who they are fully aware is a human being in their own right, and they just want to have a laugh and go home. And then there’s 10 percent that are a mixture of people who see you as a jester or cartoon character who should get up and dance for them, and people who, in their head, have a full-on relationship with you and need to protect the fragile little boy from everybody else. And that’s something that’s always been part of it, since long before I was born.

It’s my job in those situations to remember, Look, no amount of ranting about it onstage or speaking out about it publicly is going to change those attitudes. As long as I keep the healthy boundaries there, it’s fine — and that includes offstage as well. One of the things on this tour that I had to learn was like, Okay, you’ve done the show. You kept the boundaries onstage like you wanted to. But now you’re about to go out the stage door, and there’s going to be some people there, and not all of them are going to talk to you in a way that is nice. Most of them will be like, “Enjoyed the show. Can I have a selfie please?” But some of them will try and do their own version of banter with you, and it’ll be incredibly rude and disrespectful. And others will ask you for a hug or want an emotional connection with you that you can’t give them. Don’t switch off yet just because you’re offstage. You’ve got to keep switched on for this portion of it. Just really politely say, “No, you can’t have a hug. But would you like a selfie?”

In the past, I used to try and reason with those people, and that’s a non-starter. I’d try to say to them, “Why would you say that really rude joke to me? What makes you think I want to hear that?” And they would just stare back at you because they don’t give a fuck, and if anything, they’re delighted that they’ve wound you up. Then, with the people who want a cuddle from you, if you say to them, “You know that’s inappropriate to ask me that, right?”, they look like they’re about to burst into tears. That’s always going to happen, and I’m the one who has to accept what I can’t control.

So there’s no longer any part of you who thinks, I’m Pagliacci! I’m the guy from the parable?

Yeah, everyone goes to that, but remember: That clown is going to therapy, That’s the first therapy session. I like to think that there’s more sessions down the line where he figured it out. I think he just didn’t find the right therapist in that situation.

Now that the tour is over and the special is coming out, where are you in terms of your relationship with your audience?

A much better place. I learned an awful lot from the tour — not only with how I was onstage, but also how we booked the tour. I was doing residencies instead of a different venue every single night, and I had a week in between residencies, so I wasn’t wearing myself out. I only went back to places where I’d had really great gigs in the past and where I knew I would enjoy it. I’m going to carry forward all of that into the next tour. I want to do another tour, which is crazy. Usually, at the end of a tour, I want to put that off as much as possible.

The other night, I did a live podcast in L.A. — How Did This Get Made? — and an audience member got involved at one point telling me to do something. It was an admin thing; it wasn’t material. They told me to sort the projector out, and I went in on them. It was the first time I’d gone in on someone since 2019, but I was able to do it in a way that was purely comedic, and the person on the other end knew that it was just me being funny and there was no malice in it. That felt nice to be like, Everyone in the room is laughing for the right reasons.

The last joke in Hecklers Welcome is all about how hard it is to write stand-up from a place of a loving, healthy relationship. To the extent all stand-up is about the comedian’s relationship with their audience, are you worried it’ll be hard to write material now that your relationship with them is healthy?

I don’t worry about it, but if it is difficult, I’ll take that. I know the alternative, and I don’t want to do that anymore. It’s one of those things we debate: Do you have to suffer for your art? Do you have to be miserable? Do you have to have someone like J.K. Simmons on your back all the time in order to be great? I’ve definitely gotten to the point now where I’m like, I don’t know the answer to that, but I know that I value my well-being and my life way more than I value how well a gig goes. There’s a load of different things I want to try with the writing and the developing of my next stand-up show, and I want it to be as good as possible and better than the stuff I’ve done in the past. But if it turns out that the only way to do that is through pain and misery, I’m not going to do that, and that’s fine.

My relationship with the audience isn’t even happy or healthy. It’s just that I’m not relying on them to feel good at a gig. For years, I would focus on, They didn’t laugh as much as I wanted them to. That was shit. Now, what I tend to focus on is, Okay, that wasn’t a great show, but I probably moved the show forward a millimeter, and actually, the reason that routine didn’t work is because you performed it differently, so let’s learn from that. I think, hopefully, that’s the way forward. But we’ll see. It’s been guesswork since day one, and I’ll continue to guess and see if it pays off.

Related