When top ocean predators vanish, the ecosystems they leave behind don’t just adapt—they transform in surprising and troubling ways. New research from South Africa sheds light on the cascading effects caused by the sudden disappearance of great white sharks, providing a rare glimpse into how marine life responds when apex predators vanish.

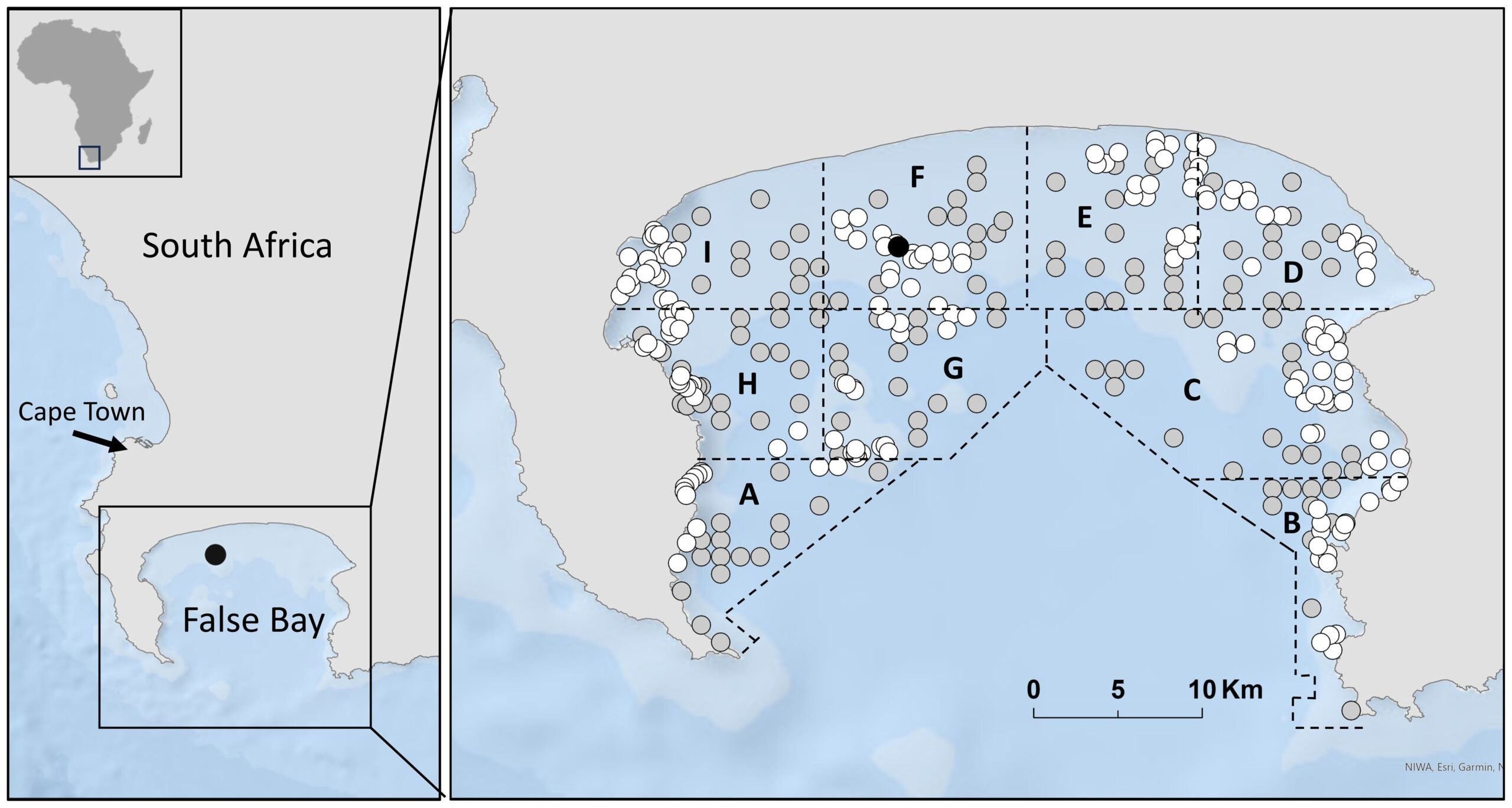

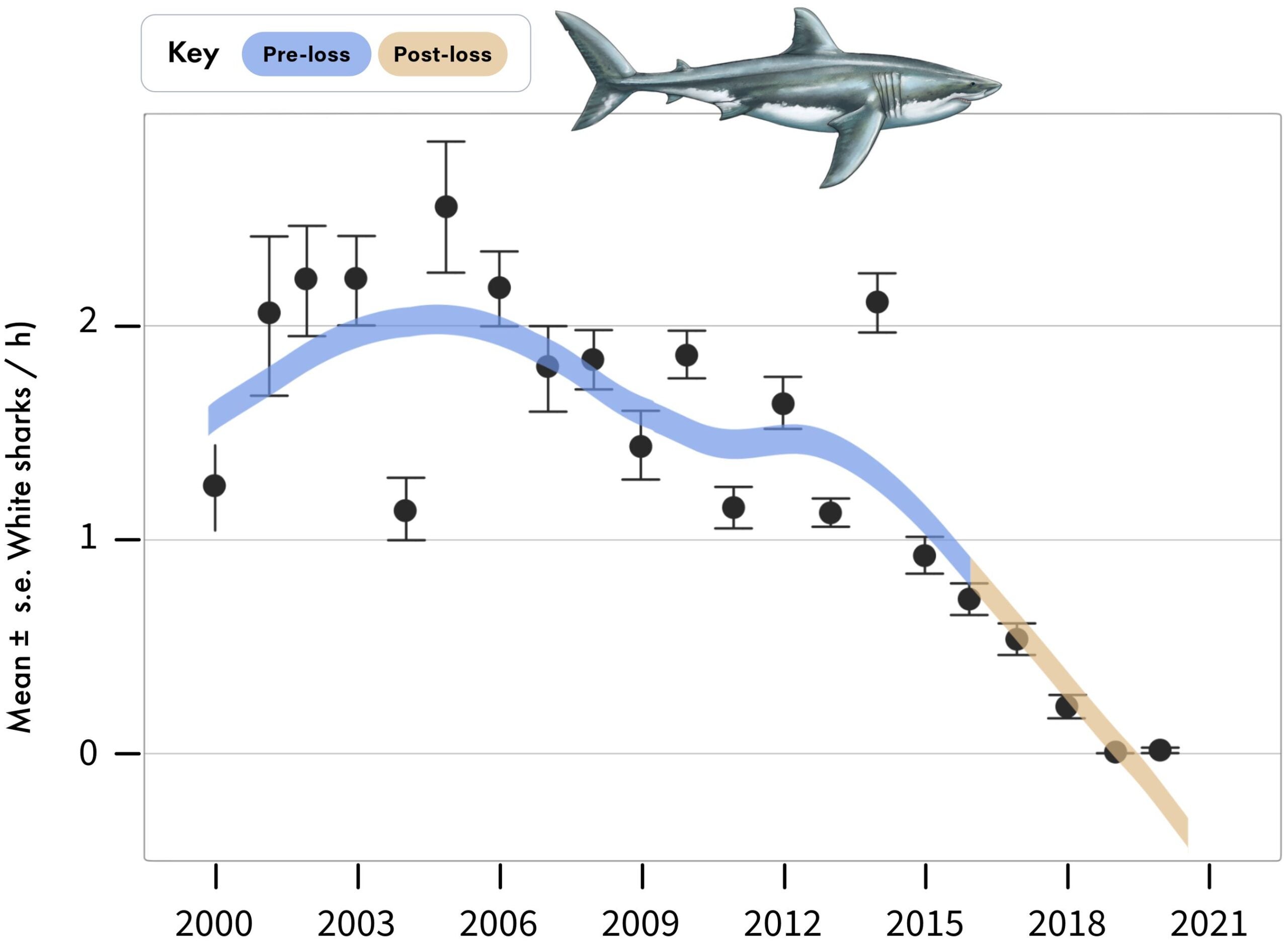

For over two decades, marine researchers at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science, have tracked sharks around Seal Island in False Bay, South Africa. They recorded how often white sharks appeared, providing valuable data on shark populations. Between 2000 and 2015, these sharks showed stable numbers. After 2015, however, sightings dropped sharply, and by mid-2018, the sharks vanished entirely.

Scientists still debate why white sharks disappeared from False Bay. Fishing nets designed to protect swimmers likely played a role, capturing and killing many sharks. Recent studies suggest attacks by specialized orcas might also have contributed to their decline. Whatever the exact reason, the loss of these iconic predators triggered dramatic ecological shifts beneath the waves.

Before their disappearance, great white sharks were frequent visitors near Seal Island, home to thousands of Cape fur seals. The presence of sharks shaped the seals’ behavior dramatically. Seals rarely strayed far from the island, knowing venturing out could lead to deadly encounters. Sharks enforced this invisible boundary, maintaining balance between predator and prey.

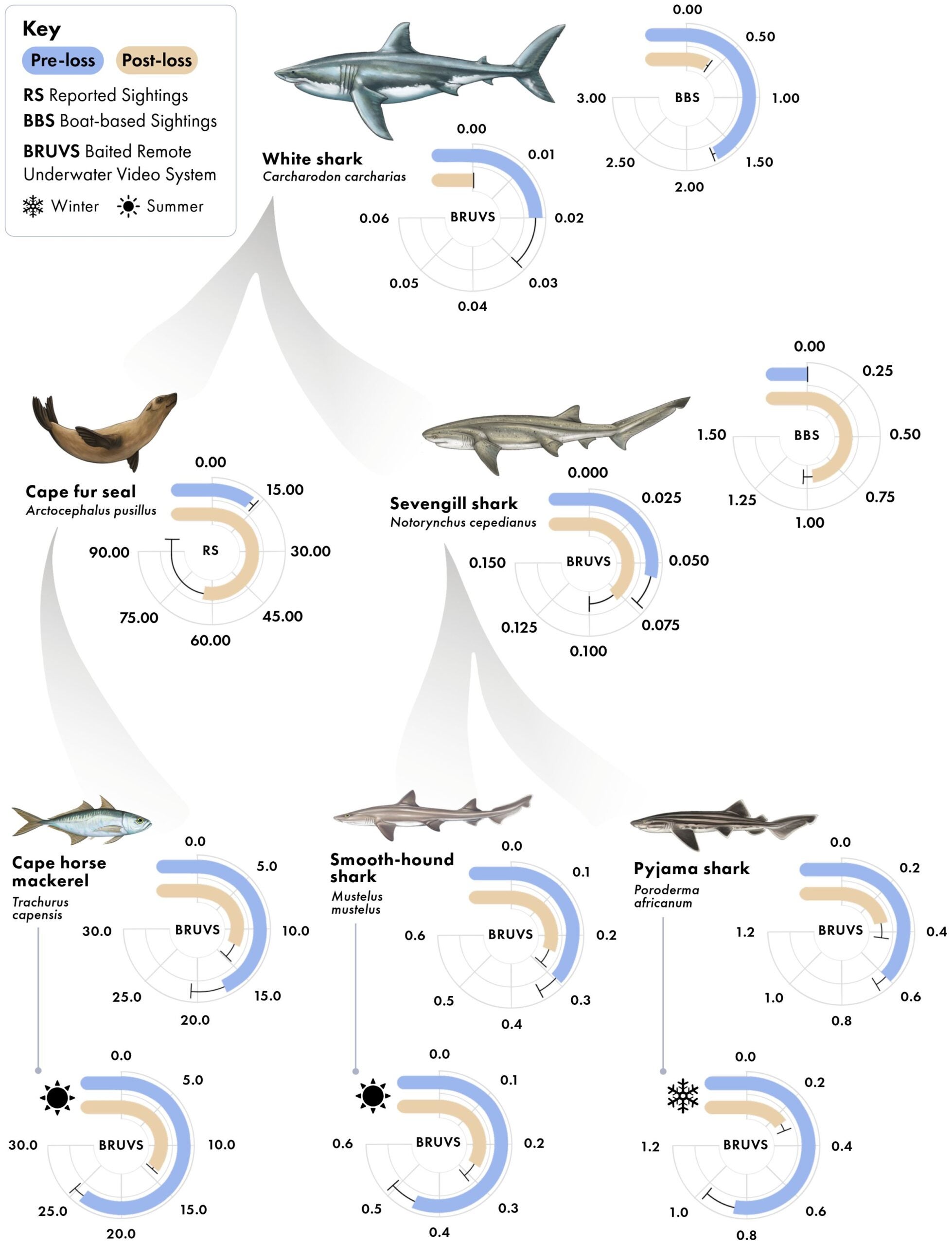

With sharks gone, this balance collapsed. Seals began swimming much farther from the safety of Seal Island. Their behavior changed quickly—researchers saw stress hormones in seals drop significantly. Without the constant threat of shark attack, seals felt safer exploring larger areas. But while good news for the seals, their newfound freedom created problems elsewhere in the food web.

More seals traveling greater distances meant more feeding pressure on fish populations further offshore. Fish like anchovies and sardines, essential food sources for many marine animals, saw numbers decline noticeably. Less prey availability doesn’t just impact seals—it harms seabirds, dolphins, and other fish species dependent on those same resources.

Related Stories

Neil Hammerschlag, the lead scientist behind this study, explained: “The loss of this iconic apex predator has led to an increase in sightings of Cape fur seals and sevengill sharks, which in turn has coincided with a decline in the species that they rely on for food.” These findings align closely with ecological theory, which predicts removing a top predator can dramatically alter entire ecosystems.

The disappearance of white sharks didn’t just affect seals—it created opportunities for other predators. Researchers were surprised when another large shark species, the sevengill shark, began appearing around Seal Island. Historically, sevengill sharks avoided areas dominated by larger white sharks. With their main competitor gone, sevengill sharks quickly moved in.

Sevengill sharks don’t occupy exactly the same role as white sharks. Instead of focusing mainly on seals, sevengill sharks primarily hunt smaller sharks and rays. Their sudden increase in False Bay meant greater predation on these smaller species. Researchers noticed sharp declines in these smaller sharks, further destabilizing the local ecosystem.

Researchers relied on detailed observations from boat-based surveys to track shark and seal populations over two decades. They also used underwater video technology called Baited Remote Underwater Video Surveys (BRUVS). These underwater cameras attracted fish and sharks with bait, recording the diversity and behavior of marine life at different points in time.

One scientist involved in the analysis, Yakira Herskowitz, said, “The use of underwater video surveys conducted more than a decade apart provided us with a snapshot of the food web both before and after the disappearance of white sharks from False Bay. The number of individuals recorded informs us not only about abundance but also their behavior, as species under increased predation risk often become more elusive.”

Such detailed information is rare, especially when tracking large marine animals. Sharks are notoriously hard to study due to their wide-ranging behavior and the costs involved. However, this extended dataset offered unique insights into long-term ecological changes, making the research especially valuable.

Globally, shark populations have declined sharply due to overfishing, habitat loss, and accidental capture in fishing gear. Sharks sit at the top of marine food chains, regulating populations of smaller predators and prey. Their decline has sparked serious concern among ecologists, who warn losing sharks can fundamentally change ocean ecosystems.

Studies from other parts of the world, like coral reefs in Fiji and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, have also examined shark impacts. In Fiji, researchers saw that the presence of sharks affected fish behavior significantly. Fish avoided open feeding areas when sharks were near, creating protected zones for seaweed. Without sharks, seaweed rapidly took over, changing coral reef habitats.

However, not all ecosystems respond the same way. Research on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef showed environmental factors like water temperature and reef structure had a bigger influence than shark numbers. These varied findings highlight how context matters in ecology. Predicting outcomes isn’t always straightforward.

Yet the situation in False Bay clearly illustrates how the removal of sharks can trigger complex ecological shifts. According to Hammerschlag, “Without these apex predators to regulate populations, we are seeing measurable changes that could have long-term effects on ocean health.” This underlines the importance of protecting sharks to preserve ocean biodiversity.

Protecting sharks presents many challenges. Large marine predators require expansive territories and face threats across international waters. Regulations designed to protect sharks, like bans on shark finning or reducing harmful fishing gear, often struggle with enforcement. The financial and logistical challenges of protecting large, mobile marine animals add further complications.

Yet the stakes remain high. Healthy oceans sustain billions of people worldwide, providing food, recreation, and supporting economies. The loss of apex predators doesn’t just harm ecosystems—it threatens human livelihoods. Conservation efforts are critical to prevent further ecosystem disruptions like those seen in False Bay.

This study, supported by groups like the Shark Research Foundation and published openly in Frontiers in Marine Science, emphasizes the urgent need for greater shark conservation worldwide. Protecting sharks isn’t just about saving a single species. It’s about preserving the delicate web of marine life that sustains our oceans.

Hammerschlag summarized the situation clearly: “These changes align with long-established ecological theories that predict the removal of a top predator leads to cascading effects on the marine food web.” As shark populations continue to face threats globally, understanding these ripple effects grows increasingly important.

The dramatic changes seen in False Bay should serve as a clear warning. Losing top predators like white sharks has consequences that reach far beyond one species. Protecting sharks protects the health of our oceans—and ultimately, ourselves.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post The disappearance of great white sharks has scientists concerned appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.