In 1973, before their ascent to rock superstardom with Fleetwood Mac, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks were two young lovers making music in Los Angeles. Their debut album, Buckingham Nicks, though commercially unsuccessful at the time, would prove to be the catalyst that changed their lives. When Mick Fleetwood happened to walk into Sound City Studios and overhear Buckingham’s masterful guitarwork, he knew he’d found what his band desperately needed. Fleetwood invited Buckingham to join the group, and Buckingham agreed, on one condition: His musical and romantic partner, Nicks, would come too.

All this time, the band’s origin story, captured in Buckingham Nicks, has remained locked away in aging vinyl archives. But Grammy-winning guitarist Madison Cunningham and virtuoso multi-instrumentalist Andrew Bird have breathed new life into this historic recording with their own interpretation, Cunningham Bird, out now. Cunningham, celebrated for her sophisticated fingerpicking and intricate compositions, joins forces with Bird, whose distinctive violin work and plaintive vocals have earned him critical acclaim. The pair’s reimagining of this pivotal album offers fresh insight into both Fleetwood Mac’s enduring influence and the rocky romance that sparked the band’s success. For the latest episode of Switched on Pop, I sat down with the duo to discuss their approach to this legendary material and what drew them to resurrect these long-lost songs. You can hear the full episode here.

This album is an adaptation of Buckingham Nicks, which is this lost album that presages Fleetwood Mac. Could you share a bit about the story of what that record is?

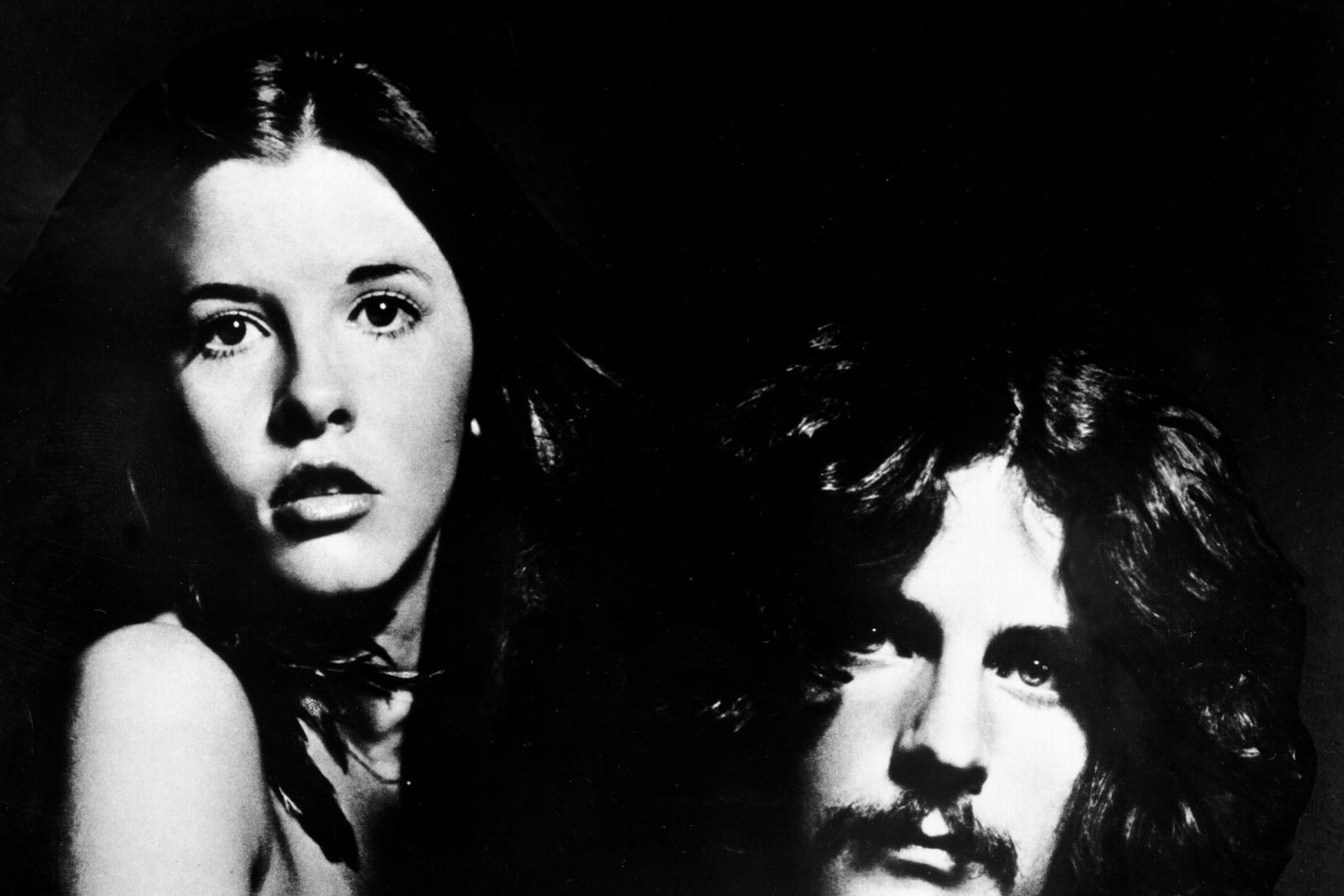

Andrew Bird: It’s the record you find in a garage sale or a used record store; everyone knows the cover — of Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks topless and looking impossibly beautiful. It was a very ambitious album that the two of them made when they were together. It kind of hinted at what was to come with Fleetwood Mac, but not many people know the music. There’s not a single measure on this album that’s not trying to impress you with some interesting studio move. You can take the bones of all these songs and strip them back — as we say, pull up the shag-rug carpeting — and kind of see what kind of space there is. The way the production was in ’73 was, was a little, you know, heavy-handed, perhaps. I identify with it in the sense of they’re young. I remember when I was making albums in my 20s, I tried to throw every interesting thing I could into every square inch of the album.

Madison Cunningham: I relate to that, too, in a lot of ways. I feel like I’ve just recently kind of grown out of the, Oh, I don’t want to play every chord and I want music to kind of feel easy.

Madison, is there a song on this record for you that captures this youthful quality?

M.C.: The first song that really grabbed my attention was “Long Distance Winner.” It sounded immediately like something Andrew and I would have written, especially the first three chords. We were honestly trying to figure out how playful to be with it. It finally got to a place where we found a marriage of the complexity we enjoy with the simplicity at the heart of the album.

I’m actually curious: Andrew, how did you end up emotionally relating to the songs? I know for myself, there was a lot of personal things I was going through that kind of started to reflect what some of the lyrics were saying.

A.B.: You were definitely going through something. I was more just worried about getting sued.

M.C.: [Laughs] That’s sweet. You were going through something, too.

A.B.: I mean, I was just trying to relax into it. The whole time I was wondering, Why are we doing this?

M.C.: It’s tricky because we couldn’t rewrite any lyrics, so our moves were few. They were really important as to what they were going to be.

This is obviously not a Fleetwood Mac–approved project. It doesn’t need to be. Was there a concern of changing any of the pronouns, as you do in some of the songs, or that Fleetwood Mac would not be happy with this project?

M.C.: My concern was, we didn’t quite know why it was out of print.

A.B.: Yeah, that made us suspicious — why you can’t stream a major record that could get a lot of attention.

What did you learn in the process?

M.C.: Uh, absolutely nothing. [Laughs]

A.B.: I learned that there’s some very vague legal language that made me a little nervous. But it’s all good. You’re allowed to cover whatever you want. I just heard anecdotally that getting the blessing of Stevie or Lindsey has not always gone well in the past for some people.

Working on any material that is Fleetwood Mac–related is in relationship to their complex relationships. How did approaching this material affect your own artistic partnership?

M.C.: I think working on this record reminded me of what I love so much about music, which is simplicity. I’m really getting to a place where I listen to music so differently than what it was even two years ago.

A.B.: In making this record, I heard things come out in Madison’s voice that I hadn’t heard before, like on “Crystal,” which was a really deep, deep sadness. It was really emotional.

What do you two think is the enduring appeal of Fleetwood Mac?

A.B.: Great melodic songwriting. But this album is also very interesting because it’s all there — the dynamic between Stevie and Lindsey became very clear as we were working on it. Lindsey is like, I’m going to go conquer the world, and you can come along if you like, but you really need to step it up. And her songs are like, And you love only the tallest trees. It’s like a conversation or argument between two lovers. Together, they make up the full range of how you can live.

M.C.: Obviously Fleetwood Mac was many things, but I think Stevie is also just — has an unforgettable voice. Nobody sounds like her. I just heard “Dreams” the other night, and I jokingly said, “Oh, not ‘Dreams’ again.” But as the song played, talk about a two-chord song that isn’t boring and still has arc and dynamic. And I think they really found what it means to be classic.