The human brain, a marvel of biological engineering, operates at a surprisingly modest pace when it comes to processing information.

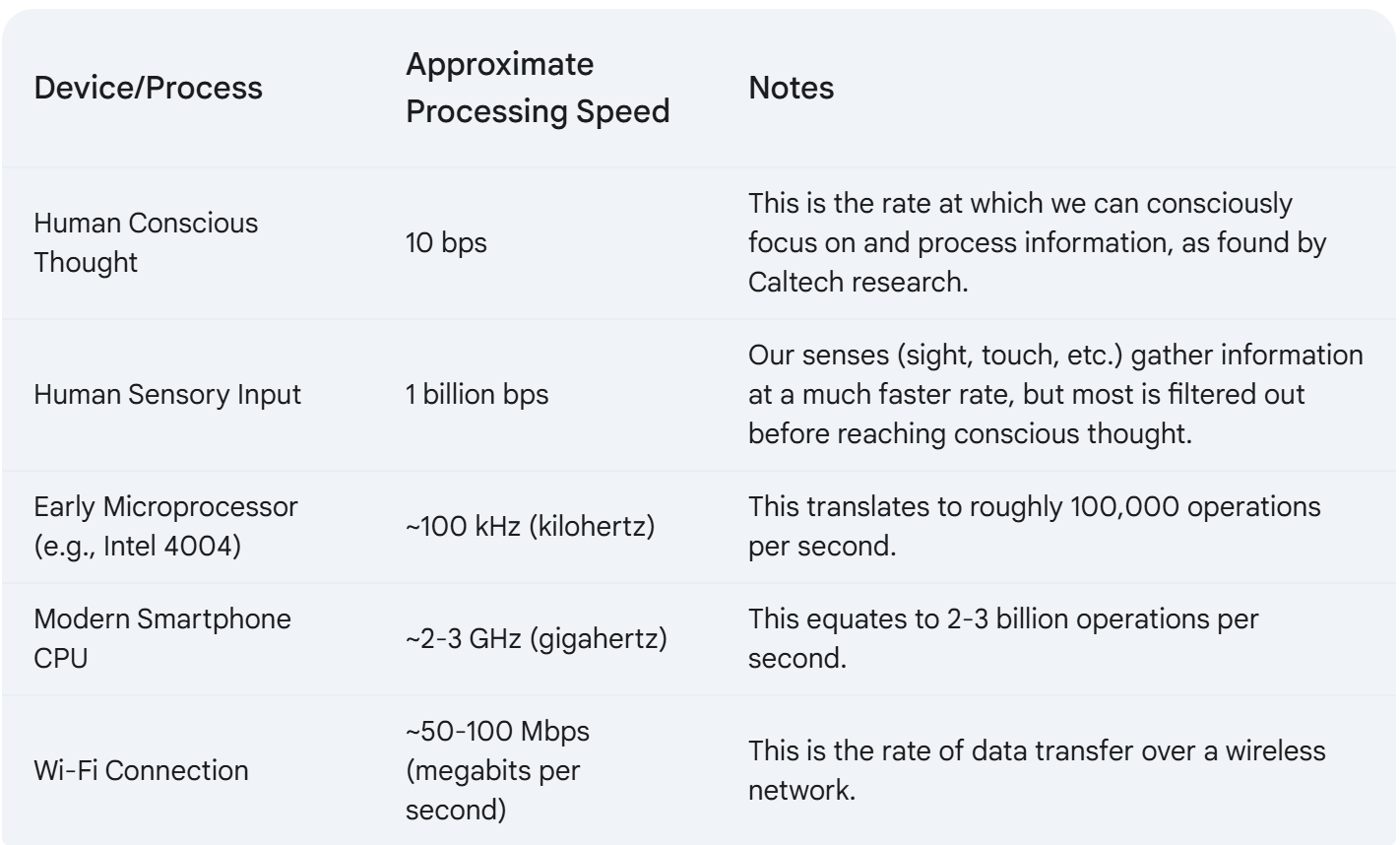

Despite the immense sensory data absorbed by our bodies—about a billion bits per second—our thought processes run at a meager 10 bits per second. This disparity, uncovered by recent research, raises fundamental questions about how we perceive and interact with the world.

In a study led by Jieyu Zheng at Caltech, researchers used information theory to analyze decades of literature on human cognition.

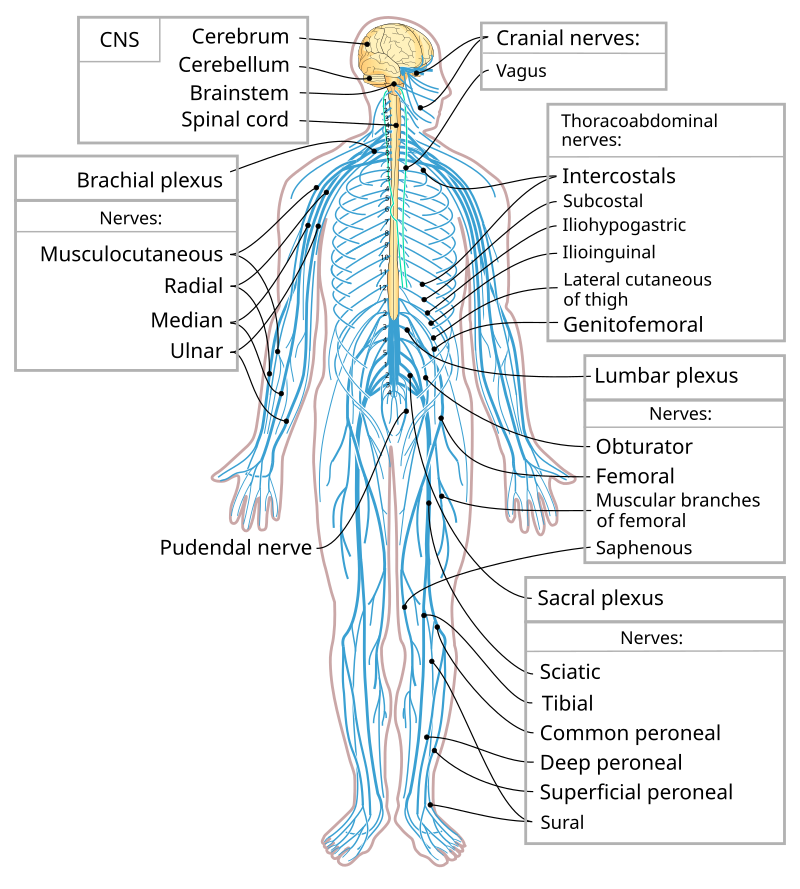

The findings revealed that, while the peripheral nervous system gathers vast amounts of environmental data at lightning speed, the brain filters this input down to a trickle of 10 bits per second for conscious thought. For context, a typical Wi-Fi connection handles around 50 million bits per second.

“This is an extremely low number,” noted Markus Meister, a senior researcher in the study. “Every moment, we extract just 10 bits from the trillion that our senses take in, using those 10 to perceive the world and make decisions.”

The apparent inefficiency poses a paradox: why is our brain—an organ housing 85 billion neurons—operating so slowly? While individual neurons are capable of transmitting far more than 10 bits per second, the collective output remains constrained.

One key question arises: why does the brain, unlike the sensory systems, process only one thought at a time?

Researchers speculate that evolutionary history might provide some answers. The earliest nervous systems likely evolved to support navigation, enabling organisms to move toward food and away from predators. This evolutionary path could explain why modern human thought resembles a form of navigation—moving through a conceptual space one idea at a time.

Related Stories

In their paper, Zheng and Meister suggest that this sequential processing is embedded in the brain’s architecture. “Human thinking can be seen as a form of navigation through a space of abstract concepts,” they write. The brain’s preference for linear thought aligns with its historical role in navigating physical spaces.

Moreover, the study highlights that humans evolved in relatively slow-paced environments, where processing 10 bits per second sufficed for survival. While modern technology bombards us with information, the brain’s processing speed remains rooted in these evolutionary foundations.

This slow speed of thought has significant implications for neuroscience and future technology. For instance, tech visionaries have proposed direct brain-computer interfaces to accelerate communication. However, the study’s findings suggest that such interfaces would still operate at the brain’s intrinsic limit of 10 bits per second.

This bottleneck might explain why human behavior, from playing chess to solving puzzles, involves deliberate, sequential steps. Even a chess player envisioning potential moves can only process one sequence at a time.

The brain’s inability to process multiple trains of thought in parallel highlights a stark contrast with its sensory systems, which manage thousands of inputs simultaneously.

Markus Meister emphasized the need for future research to address these paradoxes. Understanding why the brain filters vast amounts of sensory data into such a limited stream of conscious thought could unlock new insights into its design and function.

While the brain’s slow thought speed might seem like a limitation, it’s essential to consider the context. “Our ancestors chose an ecological niche where the world is slow enough to make survival possible,” Zheng and Meister wrote. In most scenarios, the environment changes gradually, and the brain’s processing speed is adequate.

Nonetheless, the discrepancy between the sensory system’s input and the brain’s output suggests room for further exploration. Could advances in neuroscience and technology help bridge this gap? Or are these limits inherent to the brain’s structure and evolutionary design? Such questions remain open for investigation.

As scientists delve deeper into these mysteries, this research underscores the brain’s complexity. It also invites a reevaluation of assumptions about its capabilities and constraints, offering new perspectives on how we interact with both natural and artificial systems.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post The human brain is surprisingly slow, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.