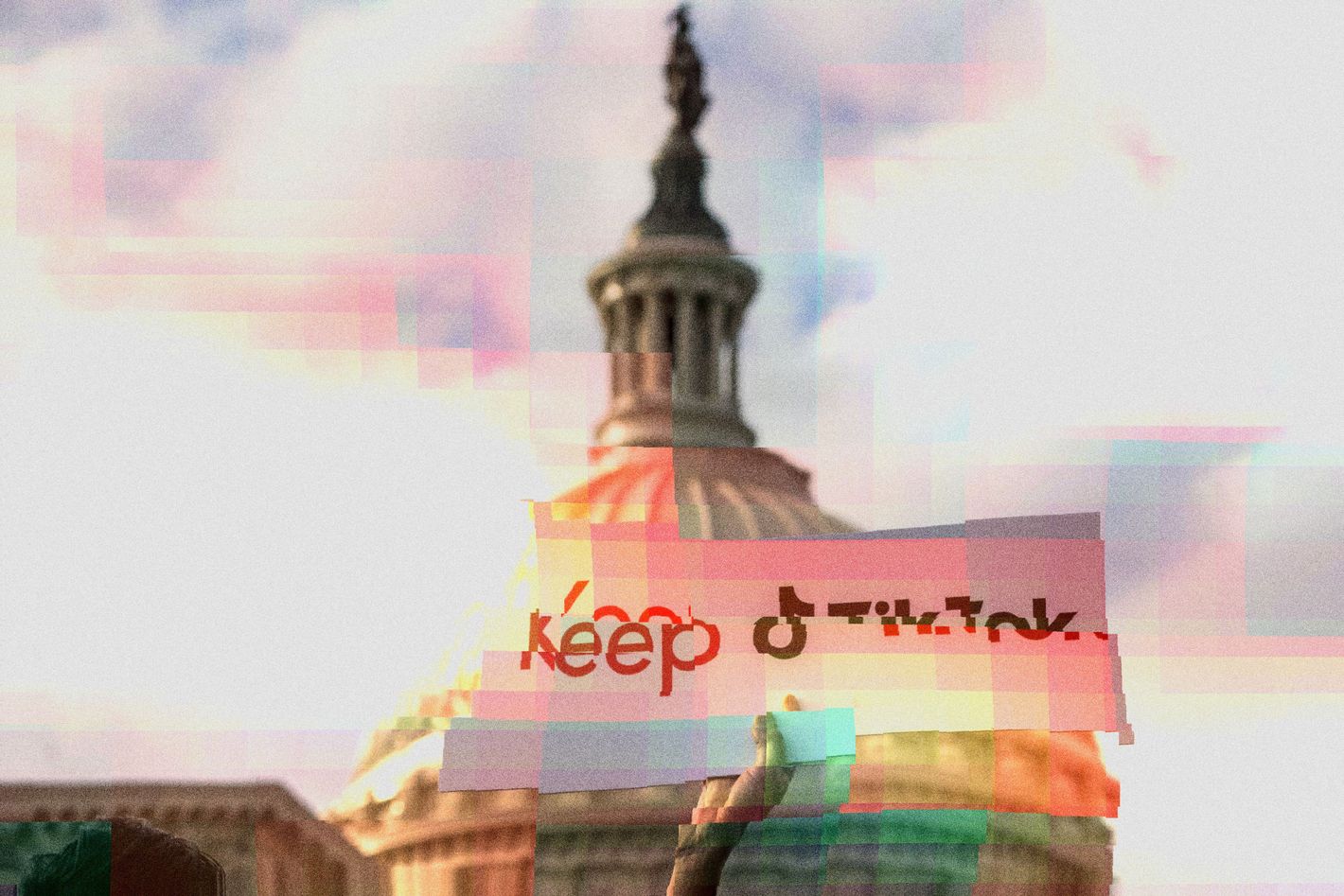

Donald Trump has made plenty of promises and threats about what might happen when he returns to office in January, most of which are continuations — and intensifications — of the policies he pursued last term. On the matter of TikTok, though, the president-elect is executing a complete and total 180: Trump, who once proposed banning the app, is now claiming he wants to save it.

If nothing changes between now and January 19th, TikTok will be banned in the U.S. one day before Trump’s inauguration. There are a number of ways it could avoid or delay this fate. Its Chinese parent company, ByteDance, could sell it, but ByteDance has ruled this out and previous talks with potential buyers have gone nowhere. TikTok could win its case against the ban in federal court; however, after a disastrous hearing in September, legal analysts aren’t confident in the company’s chances. Far more likely is a court-ordered or officially granted delay of at least 90 days, which would punt the issue to the incoming administration. The prospect of a TikTok ban has remained just over the horizon for so long that a lot of people — not just members of the general public but millions of TikTok creators (and advertisers!) who depend on it economically — have stopped taking it seriously, and I don’t really blame them. Shutting down a hugely popular social-media platform would be both unprecedented and disorienting. It sounds made up! But it’s also written into law.

And though it may be hard to remember now, this all started with our once and future leader. In 2020, just two years after TikTok officially launched in the U.S., then-President Trump attempted to ban TikTok by executive order, citing threats of blackmail and espionage and privacy violations by the Chinese government. By that point, TikTok had already been scrutinized by Democratic and Republican lawmakers. But Trump popularized the option of simply outlawing it — or forcing its sale to an American company. “As far as TikTok is concerned, we’re banning them from the United States,” he said in July of that year. “I have that authority.”

In the months and years that followed, TikTok explored a sale, restructured its American operations, and fought the matter in court. Shortly after taking office, President Biden rescinded the executive order but replaced it with a plan that, while more “orderly” than Trump’s, pointed in the same general direction of divestment or, failing that, a ban. The bill that ultimately passed was the rare bipartisan project with broad support from lawmakers. (The general public is most likely another story: TikTok claims about 170 million users in the United States, and polling on the issue is mixed but trending against a ban.)

If you stop there, you’ve got a coherent if surprising story: Donald Trump rolled established concerns about TikTok into his broader anti-China platform and forced the issue; despite some legal and public backlash, the idea of a ban was normalized in Washington; eventually, a Democratic president signed into law a more durable and thorough piece of legislation along the same lines as Trump’s initial orders. In political and legislative terms, Trump won the argument. But he reacted to this victory strangely. He didn’t highlight his accomplishment on the campaign trail, gloat about it, or mock opponents who had previously said the ban was crazy. Instead, when it seemed clear the bill might pass, he changed his mind. “There’s a lot of good and there’s a lot of bad with TikTok, but the thing I don’t like is that without TikTok, you’re going to make Facebook bigger, and I consider Facebook to be an enemy of the people, along with a lot of the media,” he told CNBC in March. “There are a lot of people on TikTok that love it,” he said, including “young kids on TikTok who will go crazy without it.” In July, he reiterated, “I’m for TikTok.” During the campaign, he was the candidate who would “never ban” TikTok and Harris was the candidate who would let the existing process play out. (Neither talked about it very much.)

What changed? As far as the stated arguments for banning the platform — as a national security threat or as part of a protectionist industrial policy — not a lot. If anything, the argument for a ban has gotten stronger, at least on its own terms: Voluminous reporting has established clearer links between ByteDance and the Chinese government, and the app has become culturally and economically more influential in the United States.

If we try to understand this in terms of the whims, desires, needs, grudges, and political instincts of a single powerful person, it starts to make more sense. In a recent Bloomberg interview about TikTok, Donald Trump mentioned his post-January-6 Facebook suspension and continuing anger at Mark Zuckerberg; a March report in the Washington Post claimed that Trump had come to believe Zuckerberg was responsible for his 2020 loss. You can also follow the money: Billionaire megadonor Jeff Yass, a former Never Trump Republican, worked his way into Trump’s orbit personally, politically, and financially — and just so happens to own, through his investment firm, a significant piece of TikTok’s parent company. These stories point to a somewhat changed reality for the tech industry, in which the president’s personal preferences and perceptions of loyalty will become much more central to How Things Work. TikTok is still connected to a foreign company and a sanctioned government, and it still competes with American firms. But at least it’s not owned, as Donald Trump is fond of saying, by an “enemy of the people” like Mark “Zuckerschmuck.”

The most politically appealing option here, given the tepid public support for a ban that would be at least slightly disruptive to tens of millions of Americans across the ideological spectrum, would be to simply let the ban die — to pretend none of this ever happened, or to attempt to file it away as a Biden-administration misadventure. At this point, though, that’s not necessarily possible. After years of work, the campaign to ban TikTok has substantially succeeded. Now, it needs to be actively undone, and the Trump administration is probably going to have to participate in that undoing. The possibilities are not ideal. The government could get more directly involved in finding an American buyer, which ByteDance has supposedly ruled out and could risk destroying the app (Chinese export controls might prevent ByteDance from including its recommendation algorithms — the core of the platform — in a sale). Or the government could double down on a “Project Texas”–style domestic separation-and-oversight scheme, which didn’t work last time around and isn’t really compatible with the law as written. It gets messier from there, Bloomberg reports:

Trump could also urge Congress to repeal or amend its Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act, or push for entirely new legislation, both a long shot given overwhelming bipartisan support for the original bill. Trump could theoretically direct his Justice Department not to enforce the law, or to do so selectively, but that could put American tech firms in a precarious position. The existing law places the onus on companies like Apple Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google to pull TikTok off their US app stores, and for web services providers to stop hosting its traffic; they’ll quickly rack up enormous fines if they don’t.

Trump could also take some other action seeking to overturn the legislation, like an executive order opposite the one he tried to deploy in 2020.

Any such actions will require, or at least invite, some rhetorical contortions here. Such contortions are already on offer from recently resurrected omni-surrogate Kellyanne Conway, who has been defending the app on behalf of the Club for Growth, which counts Yass among its largest donors. “There are many ways to hold China to account outside alienating 180 million U.S. users each month,” she told the Washington Post. “Trump recognized early on that Democrats are the party of bans — gas-powered cars, menthol cigarettes, vapes, plastic straws and TikTok.” A legislative approach would represent an early test of Trump’s ability to force recently anti-TikTok lawmakers to get in line. (In the House, the bill passed 352-65 with near-total Republican support.)

I won’t pretend to know what’s going to happen. But one possibility here stands out as strange yet plausible and almost surreally disconnected from the past six years of debate on the subject. In 2020, Donald Trump saw a political opportunity in banning TikTok. In 2025, he might see another opportunity in leading the campaign to save it.