Central vision can fade slowly with age-related macular degeneration. Faces blur. Words smear on a page. A dark spot can sit in the middle of what you try to see. For many older Americans, that loss becomes permanent.

At the USC Roski Eye Institute, part of Keck Medicine of USC, researchers are testing a new approach for advanced dry age-related macular degeneration. Retinal surgeon Sun Young Lee, MD, PhD, serves as principal investigator at the Keck Medicine study site. Ophthalmologist Rodrigo Antonio Brant Fernandes, MD, PhD, is the study surgeon. Their work builds on earlier human testing of a stem cell based retinal implant.

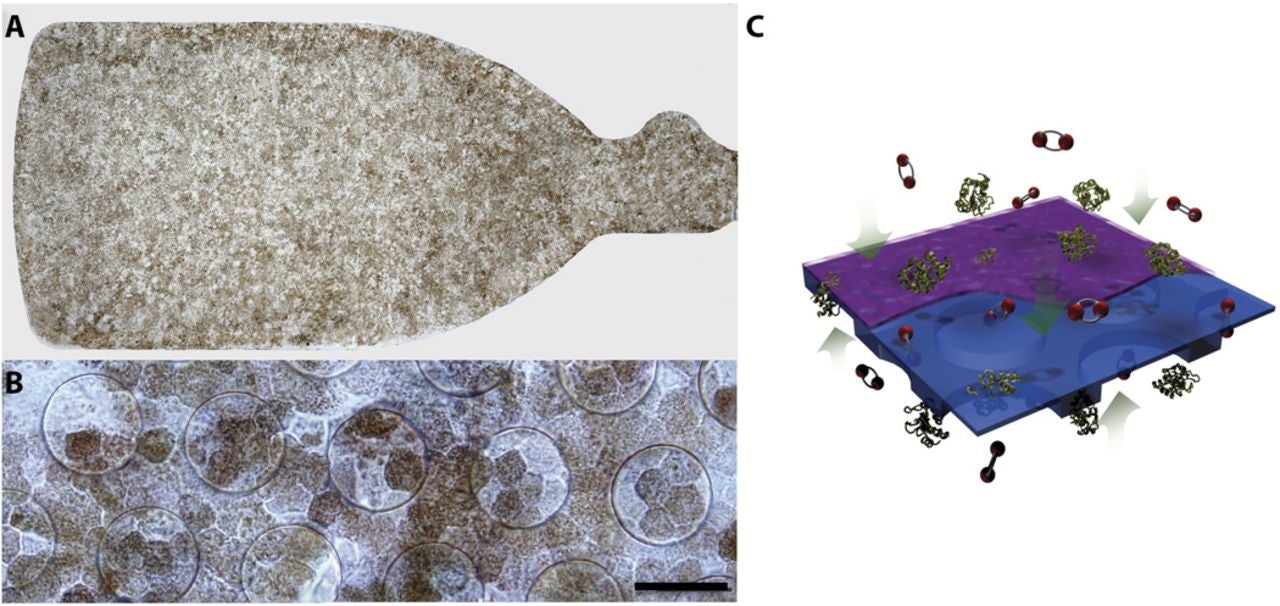

The implant pairs lab-grown retinal pigment epithelium cells with an ultra-thin support layer. It is thinner than a strand of hair. Surgeons place it into the retina during an outpatient procedure. The goal is simple to state and hard to achieve: replace damaged support cells and bring back useful vision.

“We are hoping to determine if the stem-cell based retinal implant can not only stop the progression of dry age-related macular degeneration, but actually improve patients’ vision,” said Lee. “The findings could be groundbreaking because while there are a few treatments available that delay the progress of macular degeneration, there are none able to reverse the damage already done.”

Roughly 20 million Americans live with age-related macular degeneration. The disease targets the macula, a small central part of the retina that supports sharp vision. When the macula deteriorates, the detail you need for reading, driving, and recognizing faces can disappear.

In advanced dry disease, a key problem is failure of retinal pigment epithelium, often shortened to RPE. These cells help keep the retina’s light-sensing cells alive. When RPE cells die across patches of the macula, doctors call the damage geographic atrophy. That atrophy can include the fovea, the center of your sharpest vision.

Researchers still debate the exact causes that drive geographic atrophy. Past work has shown some ways to slow earlier stages. One large trial, the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, found antioxidant therapy reduced the rate at which intermediate disease progressed. But advanced dry disease has remained a stubborn gap. Once large areas of RPE vanish, doctors have had no reliable way to rebuild what was lost.

Stem cell science has offered a possible path. Scientists can guide embryonic stem cells into RPE-like cells in the lab. Earlier clinical studies tried injecting those cells as a suspension under the retina. Some people developed new pigment patterns. Yet the cells often ended up at the edges of damage, or outside the areas that needed repair most. That raised doubts about whether loose cells could form a stable, working layer.

Another approach used induced pluripotent stem cell derived RPE in a sheet. It showed feasibility and safety in one person with neovascular disease. It did not show visual improvement, and doctors saw clumping rather than an even layer.

Those lessons shaped the strategy now under testing at USC and other sites. The idea is not only to deliver RPE cells, but to give them a surface that helps them settle, align, and stay put.

The newer device is known as the California Project to Cure Blindness–Retinal Pigment Epithelium 1, or CPCB-RPE1. It is a composite implant: a polarized monolayer of human embryonic stem cell derived RPE grown on a synthetic parylene substrate.

Parylene is a medical-grade polymer. The substrate is designed to mimic key features of Bruch’s membrane, the thin layer that healthy RPE normally sits on. Bruch’s membrane changes with age, and those changes can disrupt cell attachment and metabolism. By recreating a supportive surface, researchers hope the implanted cells act more like native RPE.

In this design, the parylene membrane is about 6 microns thick. It includes regions that support diffusion of nutrients and growth factors. It also has a smooth surface that promotes cell adherence. Animal studies suggested the approach could work. Comparative work in rats indicated RPE grown on this substrate survived longer than injected cell suspensions. The team also showed feasibility of implantation in minipigs.

Now, a larger phase 2b clinical trial is beginning. Keck Medicine of USC is one of five sites nationwide. The study is masked. Some participants receive the implant. Others undergo a simulated procedure. Eligibility includes adults ages 55 to 90 with advanced dry disease and geographic atrophy. Researchers plan to follow participants for at least one year and enroll 24 patients.

“The study will explore if the lab-engineered implant will take over for the damaged cells, function as normal RPE cells would, and improve vision for patients who may currently have no other options for improvement,” said Rodrigo Antonio Brant Fernandes.

The new trial builds on earlier work that enrolled a small group. USC specialists reported that the implant appeared safe, stayed in position, and became absorbed into retinal tissue. In that early group, 27% of participants had some level of vision improvement.

“The earlier phase of the clinical trial showed the treatment to be safe with the potential to benefit patients’ vision; this next phase will investigate whether the therapy can achieve clinically significant improvements in vision,” Lee told The Brighter Side of New.

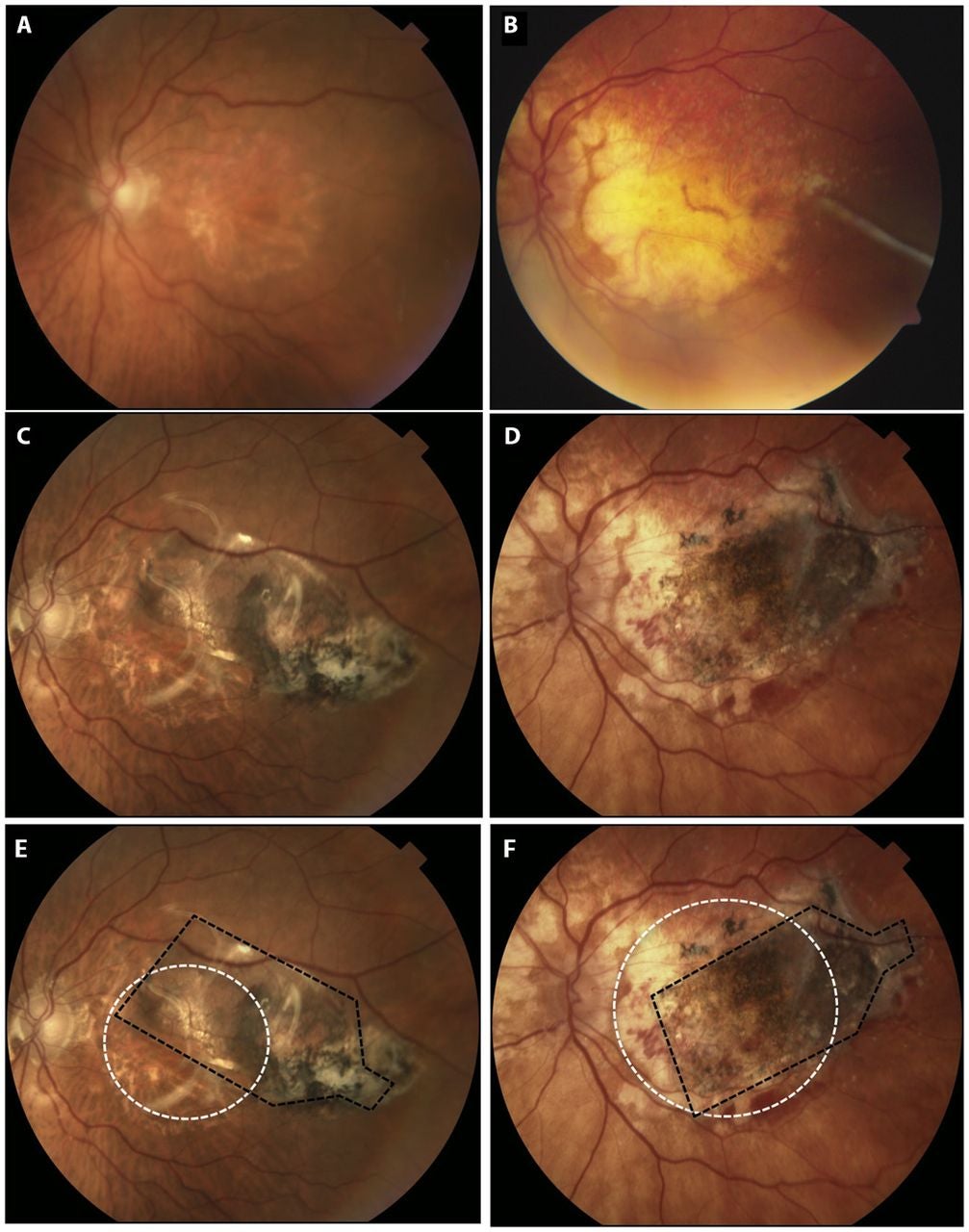

A related first-in-human phase 1/2a report described outcomes in five subjects with advanced non-neovascular disease and severe vision loss. Surgeons successfully implanted four people. One person did not receive the implant because fibrinoid debris in the subretinal space blocked delivery. That participant still counted in the intent-to-treat analysis. After that event, surgeons adjusted the method to reduce debris buildup.

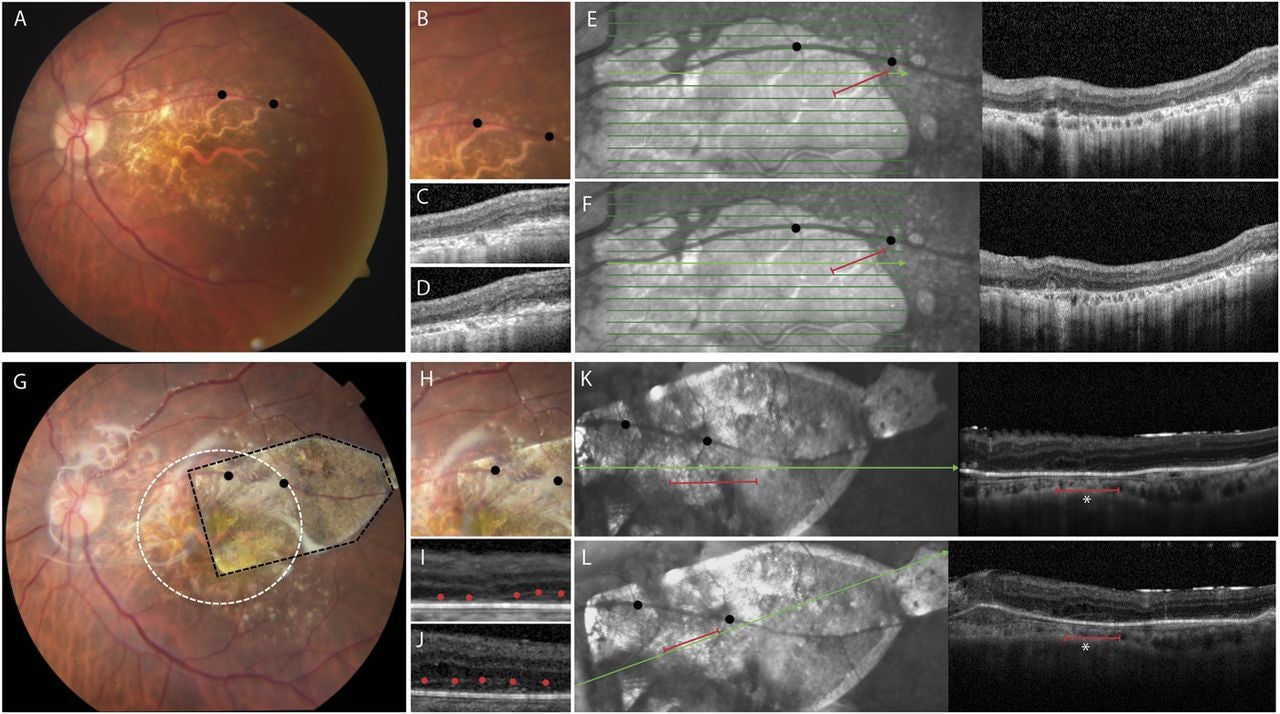

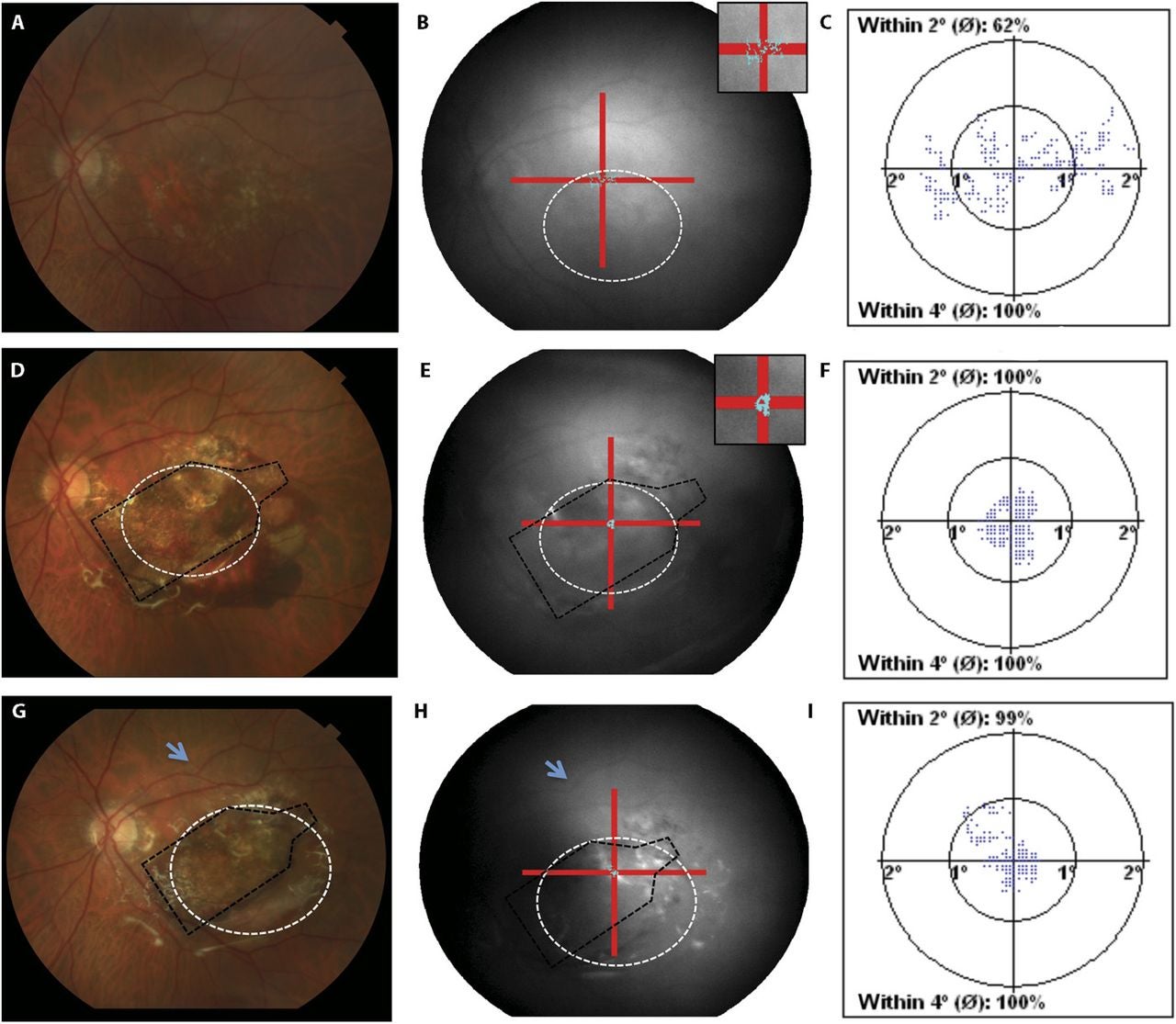

Researchers tracked vision using ETDRS letter scores and LogMAR measurements. They also used optical coherence tomography, or OCT, to examine retinal structure. Fixation stability testing measured how consistently the eye held focus on a target.

Follow-up ranged from 120 to 365 days, with an average of 260 days. The implant’s location, pigmentation, and size did not change during follow-up, suggesting stable positioning.

In the study eyes, baseline vision ranged from 3 to 32 ETDRS letters. Four of five subjects showed no substantial change. One subject improved by 17 letters at day 60, and that gain persisted through day 120. In fellow eyes, overall change was not significant, though two people lost 11 to 14 letters over the same period.

OCT images added another clue. Before implantation, scans showed no RPE monolayer in the atrophic region. They also showed minimal evidence of outer retinal layers within the damaged zone. After implantation, imaging showed the device in place. Some scans also showed hyperreflective bands in the outer retina above the implant, consistent with integration of implanted RPE with overlying tissue.

Fixation results pointed in the same direction. Two subjects improved from unstable to stable fixation after implantation. In one subject, fixation shifted over the implant and into the middle of the atrophic area. In small samples, statistical power remains limited, but the pattern suggested a possible functional benefit.

Safety results were encouraging but not perfect. The study reported no unanticipated severe adverse events linked to the implant, surgery, or immunosuppression. One anticipated serious event possibly tied to surgery was a subretinal hemorrhage detected during follow-up in one subject. The hemorrhage largely resolved, and the implant was unaffected. Mild to moderate subretinal hemorrhages occurred in other cases and resolved without intervention. Two systemic serious adverse events occurred, both described as unrelated to the eye procedure.

If the phase 2b trial confirms meaningful vision gains, the impact could be immediate for people with advanced dry age-related macular degeneration. Today, most options focus on slowing decline, not rebuilding damaged tissue. A successful implant could shift care toward repair, especially for patients with geographic atrophy who have few alternatives.

The work could also guide the next generation of cell therapies. The scaffold approach addresses a practical problem in regenerative medicine: transplanted cells often fail when they lack the right surface and structure. If a stable RPE layer restores function, researchers may apply similar strategies to other retinal diseases and to other tissues that require organized cell layers.

Finally, the trial may reshape how doctors measure improvement in late-stage disease. Fixation stability, structural OCT changes, and letter scores together offer a fuller picture than vision charts alone. That mix could influence future clinical trials and speed development of related treatments.

Research findings are available online in the journal Cell.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Tiny eye implant could restore vision lost to macular degeneration appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.